Of the more than 2.7 million U.S. military service members who have served in Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) in Iraq and Afghanistan, approximately 1.9 million are eligible for health care services through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) (

1). Broken down by service branch (Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Coast Guard) and by regular or Reserve Component (RC), nearly one-third (31%) of those eligible for VHA care between 2002 and 2010 were members of the RC, which includes the Army National Guard (ARNG) and Army Reserve (AR) (

2).

To assess health status at two time points after OEF/OIF/OND deployments, service members complete the Department of Defense (DoD) Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) shortly after returning from deployments and a follow-up Post-Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA), usually between three and six months after returning from deployments. The PDHA and PDHRA include screens for alcohol misuse, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which are common behavioral health concerns for this population (

3,

4). In a study of Army soldiers returning from Iraq, approximately 20% of active-duty members and 42% of RC members were in need of a referral for or were already receiving behavioral health care (

5). Although the aforementioned study and others (

6,

7) have examined postdeployment behavioral health screens, referrals, and use of services in military health care facilities (that is, not in the VHA), none have examined whether screening positive is associated with receiving care in VHA after demobilization from the military (when “veteran” status is conferred and the individual is eligible for VHA care). Because most RC members complete the PDHRA after they have demobilized, many may no longer be eligible for or have access to health care in military health care facilities; thus, it is difficult to assess with DoD data alone whether those who screen positive for alcohol misuse, depression, and PTSD receive needed services thereafter.

The study reported here addressed this gap in understanding by combining behavioral health screen data (PDHRA) from DoD with enrollment and utilization data from VHA. We examined whether screening positive for PTSD, depression, or alcohol misuse on the PDHRA was associated with receiving care from (“linking to”) VHA after RC members demobilized from the Army. In other words, we were interested in whether veterans who may have been most in need of behavioral health care were more likely to link to VHA than veterans who may have had less need. We also analyzed the association between PDHRA screen scores with rescreening scores in VHA, as well as subsequent diagnosis rates and treatment rates among those diagnosed. Examining scores on VHA screens administered within six months of the PDHRA provided insights into how often problems identified by screening changed over time, such as how often members who screened negative for problems screened positive for problems once rescreened in VHA. These data shed light on the consistency of screening scores in DoD and VHA and have implications for the frequency and timing of screening for alcohol misuse, depression, and PTSD. Finally, the rates of specialty behavioral health and medication treatment after diagnosis among newly returned and VHA-enrolled RC members have not been examined.

Methods

We used data from the Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat (SUPIC) study, an observational, longitudinal study of Army service members who returned from OEF/OIF deployments during fiscal years (FYs) 2008–2011 (

8) and combined these data with VHA enrollment and utilization data. We extended previous analyses, which determined predictors of enrollment in and utilization of care at (linkage to) VHA after RC members demobilized from the Army (

9,

10). To assess whether OEF/OIF Army RC members with positive screening scores received needed care, we examined the association between positive screening scores derived from the PDHRA and linkage to VHA, along with subsequent rescreening scores, diagnosis, and treatment in VHA among those who linked.

Samples

Among the SUPIC RC members who demobilized between FY 2008 and FY 2011, we first selected service members who completed a PDHRA (N=142,846); some of the SUPIC sample did not have a PDHRA associated with their index deployment. We then restricted our sample to those who had completed a PDHRA after demobilization from active duty (N=73,164), as opposed to those who had completed a PDHRA before their demobilization, when they would still be eligible for care in military facilities. The timing of the PDHRA after demobilization was important because it enabled us to study a more direct relationship between behavioral health scores and linkage to VHA within six months after completing the PDHRA. Given previous research on linkage rates that showed differences by ARNG and AR (

10) and given the different nature of behavioral health conditions and barriers to treatment for men and women (

11–

13), we divided our analyses into four groups: ARNG women (N=4,209), ARNG men (N=48,799), AR women (N=2,903), and AR men (N=17,253). [Figures and tables in an

online supplement to this article provide information on age, racial-ethnic, and other characteristics of these samples.]

A second analysis was conducted of rescreening and treatment in VHA. For this analysis, our study population was restricted to the subset of individuals who linked to VHA, which enabled us to compare the relationship between scores on the DoD PDHRA and scores on screens administered by VHA and subsequent diagnosis and treatment in VHA.

Data Sources

Data sources included deployment date information from the Contingency Tracking System of the Defense Manpower Data Center, demographic characteristics and demobilization date from the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System, and health care measures from the Military Health System Data Repository. PDHRA data came from the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Patient Administration Systems and Biostatistics Activity. VHA enrollment and utilization data came from VHA National Patient Care Databases.

Measures

Measures for linkage, screen scores, and treatment were created for this study. Linkage was an indicator variable signifying whether the service member had received any health care services (outpatient, inpatient, or residential) from a VHA facility as an enrollee within six months after completing a PDHRA. We created variables for positive screens from the consumption component of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (

14,

15), the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) (

16), and the Primary Care PTSD (PC-PTSD) (

17,

18), which were included on the PDHRA and are reliable and valid instruments for the veteran population. AUDIT-C scores were categorized into the following risk groups: 0, 1–4 (as the reference), 5–8, and 9–12. AUDIT-C scores of ≥5 are considered positive for risky drinking and are the threshold for brief intervention and follow-up in VHA (

19). A binary variable was included for both the PC-PTSD and PHQ-2 screens, with a score of ≥3 as positive.

Specialty behavioral health treatment was defined as any inpatient, residential, or outpatient encounter with both a relevant diagnosis (alcohol use disorder, depression, or PTSD) and VHA specialty location codes (clinic stop and bed-section codes) received within six months of the rescreen in VHA [see online supplement].

The lists of medications for each behavioral health condition included in our analyses were adapted from DoD/VA clinical practice guidelines (

20) [see

online supplement]. The medications include first-line medications (the preferred first choice) and broad medications (first line plus other).

Analysis

We used multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression models to predict linkage, with AUDIT-C, PHQ-2, and PC-PTSD scores as key independent variables. We included a random effect for VHA facility to account for clustering within facilities and controlled for demographic, deployment, demobilization, health, and health care characteristics. [A description of control variables used in the regression analyses is included in the online supplement.]

In our second analysis, we examined the consistency between the three screening scores derived from the PDHRA and the first VHA screen results conducted within one year after VHA enrollment, as well as subsequent diagnoses for those who screened positive, along with initiation in specialty care and medication for those who were diagnosed as having the conditions within six months after their first VHA screen. These analyses were stratified by gender and by ARNG and AR status. To assess prevalence of positive screens, we calculated the portion of our samples with positive AUDIT-C, PHQ-2, and PC-PTSD scores in VHA. For rescreening, the percentage of discordance was measured by the portion of patients who screened negative on the PDHRA and then positive in VHA or vice versa. To assess prevalence of diagnosis, we calculated the portion of our samples who screened positive in VHA and were subsequently diagnosed in VHA as having an alcohol use disorder, depression, or PTSD. For treatment, we calculated the portion of those diagnosed in VHA who received specialty behavioral health treatment, first-line medication, and broad medication.

All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2. The research protocol was approved at Brandeis University, Stanford University, the VA Palo Alto Health Care System, and the Human Research Protection Program of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness.

Results

Of the 142,846 Army RC members with an index deployment and PDHRA between FYs 2008 and 2011, a total of 73,164 completed the PDHRA after demobilizing from active duty [see online supplement]. In tests of independent proportions, ARNG and AR women were more likely to link to VHA (41% and 29%, respectively) than their male counterparts (38% and 23%, respectively) six months after completing the PDHRA (p<.001 for both). For both men and women, ARNG members were more likely than AR members to link to VHA six months after completing the PDHRA (p<.001).

Our descriptive analyses of behavioral health scores revealed some notable similarities and differences between groups. A much greater proportion of men than women had positive AUDIT-C scores (ARNG, 28% versus 15%; AR, 23% versus 11%), and a slightly greater proportion of women than men had positive PHQ-2 scores (ARNG, 10% versus 7%; AR, 9% versus 7%) (

Table 1). In addition, 8% of both men and women in ARNG had positive PC-PTSD scores; and 9% of women and 8% of men in AR had positive PC-PTSD scores. In a separate analysis, we found that the rate of positive screens was higher for those who linked to VHA than for those who did not link [see

online supplement]. When we examined differences between those who did not enroll in VHA versus those who enrolled without VHA utilization, a clear pattern did not exist.

The regression results predicting linkage showed important differences by gender and ARNG and AR status. Regression results (odds ratios and confidence intervals) for key independent variables are presented in

Table 2 [for results for control variables, see

online supplement]. Among ARNG and AR men, those with positive screen scores in each area were more likely than those who did not screen positive to link to VHA, although the finding was not statistically significant for AR men scoring 9–12 on the AUDIT-C. Among ARNG and AR women, those with a positive PC-PTSD score had higher odds of linking than those who did not screen positive. Among AR women, those with a positive PHQ-2 score had higher odds of linking than those who did not have a positive score. Among the 25,168 RC members with a completed PDHRA who linked to VHA within six months after demobilization, the same patterns of differences in screen scores between males and females were observed (

Table 3) [for other characteristics, see

online supplement].

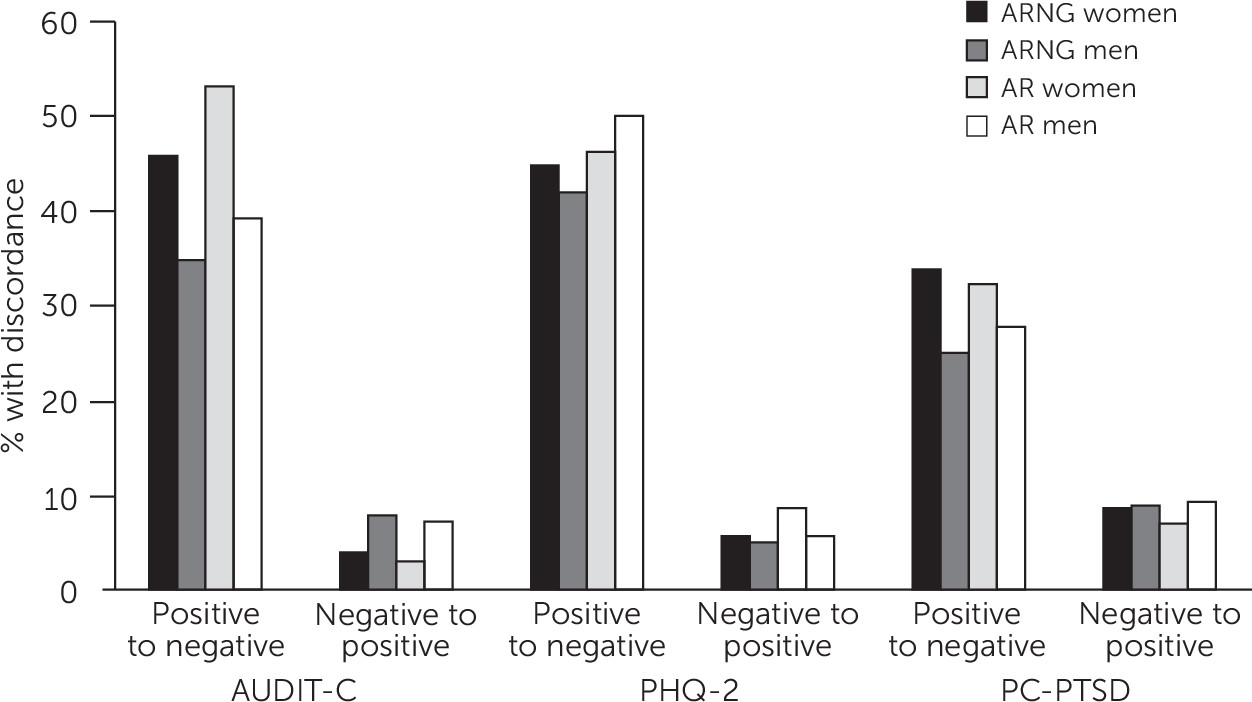

The rates of discordance between screens included on the PDHRA and rescreening results obtained in VHA for the four samples are presented in

Figure 1 [underlying data are available for reference in the

online supplement]. Having a positive screening score that turned negative on rescreening in VHA was much more common than having a negative screening score turn positive on rescreening in VHA. Across gender and component, approximately 25%−53% of veterans who screened positive for a behavioral health problem on the PDHRA rescreened negative within six months in VHA. Conversely, approximately 3%−9% of veterans who screened negative for a behavioral health problem on the PDHRA rescreened positive within six months in VHA. The screen results for PTSD appeared more stable than for PHQ-2 and AUDIT-C.

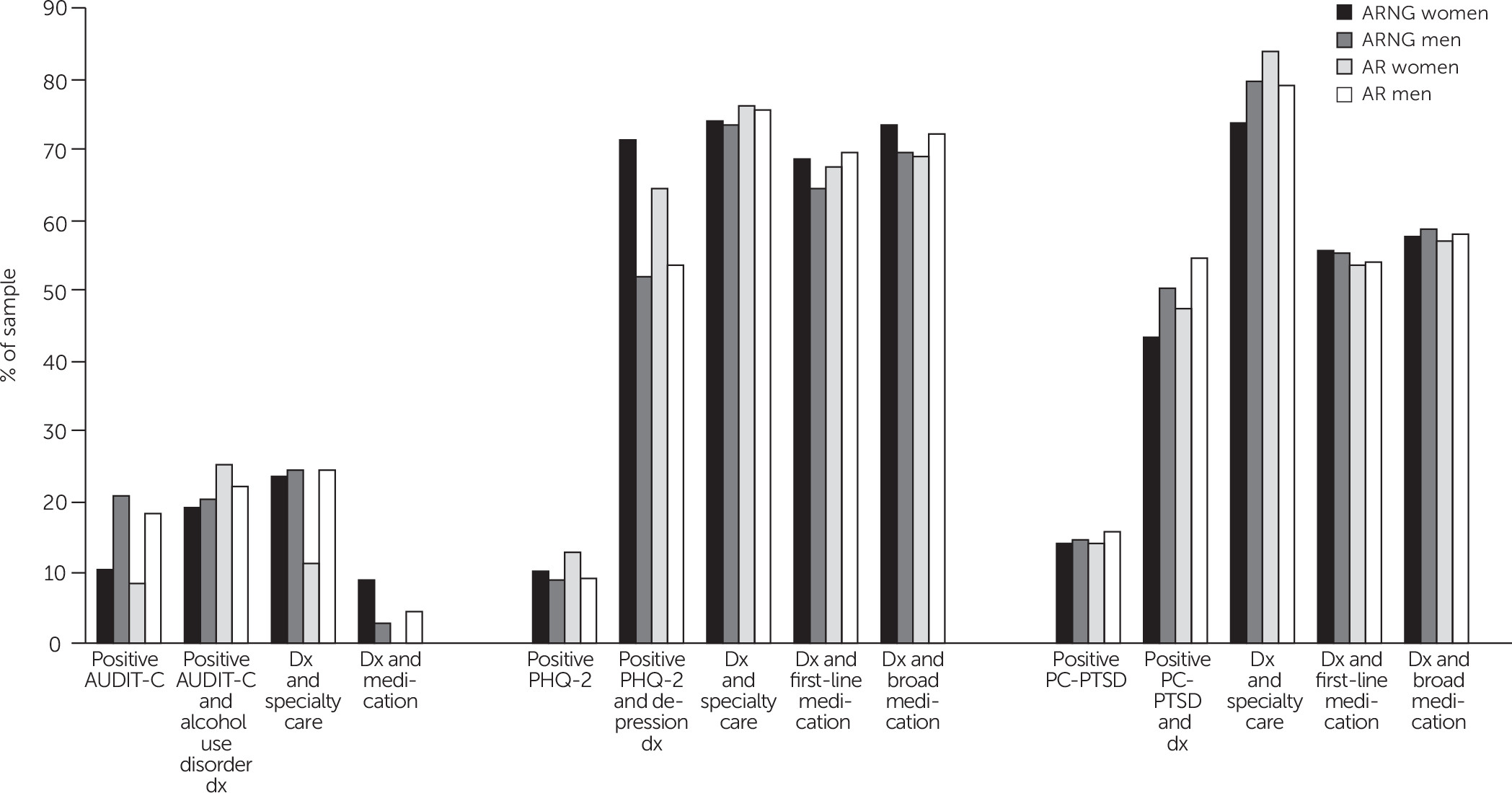

Among patients who screened positive and were subsequently diagnosed in VHA, psychosocial and pharmacological treatment engagement was much higher for those with depression and PTSD than for those with an alcohol use disorder (

Figure 2) [underlying data are available for reference in the

online supplement]. Of those diagnosed, 73%−76% received depression specialty care, 65%−69% received first-line medication for major depressive disorder, and 69%−73% received broad medication for major depressive disorder. The portion of those treated was similarly high for PTSD. Of those diagnosed, 74%−84% received PTSD specialty care, 54%−56% received PTSD first-line medication, and 57%−58% received PTSD broad medication. The percentages treated were much smaller for alcohol use disorder. Of those diagnosed, only 11%−25% received alcohol use disorder specialty care, and 0%−9% received alcohol use disorder medication.

Discussion

Overall, we found that Army RC veterans with indications of behavioral health problems, as measured by scores derived from the PDHRA, were more likely to enroll in VHA and use (or link to) VHA services than those with less apparent need. This result is perhaps unsurprising but nonetheless encouraging because VHA is an important specialty resource. VHA providers have advanced training in combat-related problems, whereas providers in the community may lack experience with these problems and may be less affordable (

21,

22). Another critical finding from our study was that behavioral health screening scores often changed between the DoD and VHA health care settings, which indicates the importance of rescreening. Keeping veterans engaged in and monitored by systems of care in which providers have military expertise ensures that care is provided more effectively and efficiently, with positive effects for veterans, systems of care, and society.

Our results have implications for the DoD-VHA transition process. Notably, the odds of linking to VHA were negatively correlated with time (cohort), although the correlations were not all statistically significant. This result may indicate that more recent outreach efforts could be improved. In addition, findings indicate a particular need to reach out to and ensure that services and VHA culture are attractive to female veterans experiencing adjustment problems (

11–

13), given that women ARNG and AR members with positive alcohol misuse scores and ARNG women with positive PHQ-2 scores were not more likely to link to VHA than women who screened negative. This information might be used to target outreach among state ARNG programs, veterans’ agencies, and programs such as the Yellow Ribbon Reintegration Program (

23), VHA Enrollment Initiative for ARNG, and Call to Action Initiative for AR. For example, those most at risk of not linking to VHA could be provided with active case management (for example, a warm hand-off) at the time of demobilization. Significant investments in case management by ARNG might help to explain the higher linkage rates among ARNG members compared with AR members, and a follow-on study could address this question. Furthermore, improving linkage could have positive consequences in addition to those discussed here (for example, suicide prevention).

We reported on the consistency of behavioral health screen scores derived from the DoD PDHRA and those administered in VHA as well as treatment patterns after diagnosis in VHA. The vast majority of veterans who had a negative score on a screen on the PDHRA had a negative score when rescreened in VHA—between 91% and 97%. Yet we also found that many veterans who had positive scores on screens included in the PDHRA screened negative by the time they were rescreened in VHA. Between 25% and 33% of the ARNG and AR members who screened positive for PTSD rescreened negative in VHA. For depression and alcohol misuse screens, the percentage rescreening negative was even higher (42%–50% and 35%−53%, respectively). These findings could represent natural remission, receipt of brief advice or supportive care from military-affiliated programs, or differences in administration methods (self-administration of the PDHRA versus administration by a clinician in VHA). Also, a nontrivial percentage of veterans who scored negative on the PDHRA screen scored positive when rescreened in VHA. These results indicate the value of timely rescreening in VHA and possible emergence of behavioral health problems over time, as well as possible differences in administration methods for the screens. Future research using surveys or qualitative methods could be conducted to ask veterans about factors that drive their changes in responses to DoD and VHA screens.

Finally, with respect to treatment, although most new VHA patients with a diagnosis of depression or of PTSD received specialty behavioral health treatment, the link to treatment for veterans with alcohol use disorder diagnoses was not strong. This suggests that stigma related to treatment for alcohol use disorder could be stronger than that for depression and PTSD. Although brief counseling and social support may reduce risky levels of alcohol consumption, this finding indicates that it is important for VHA to engage more veterans with alcohol diagnoses in treatment, such as through its Primary Care–Mental Health Integration initiative (

24).

This research had several limitations that should be considered. In previous work, we found higher linkage rates 12 months after the index demobilization date for ARNG (57%) and AR (46%) members (

9,

10). Thus the generalizability of the results reported here is limited to those who met this study’s selection criteria. For example, in our previous studies, we did not require a PDHRA completion because it was not pertinent to the related research questions. In addition, for the descriptive work on screening, diagnosis, and treatment, it is important to note that some of the sample sizes were small, which may have contributed to the variation we observed. Also, we had rescreening, diagnosis, and treatment information only for individuals who linked to VHA, and we did not know the care experience for our population outside VHA. Finally, in 2015, the PDHRA was changed: the PTSD CheckList–Civilian Version (PCL-C) replaced the PC-PTSD and the PHQ-8 replaced the PHQ-2 for depression. These instruments are not used in VHA, and screen results on the PDHRA may differ with these new measures.

Conclusions

This study is the first multivariate analysis of DoD and VHA data to assess linkage for veterans with possible behavioral health needs. Army RC members with more serious behavioral health needs assessed approximately three to six months postdeployment and after demobilization were more likely that those with less need to link to VHA. Notable differences between men and women were found. Although positive PTSD and depression screens were associated with linkage for both men and women, positive alcohol misuse screens were associated with linkage for men only. Finally, in this sample of veterans who were recently demobilized after a deployment and who linked to VHA, engagement in treatment in VHA was much lower for alcohol use disorder than for depression and PTSD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kennell and Associates, Inc., for compiling data files used in these analyses. The Defense Health Agency’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Office and the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Patient Administration Systems and Biostatistics Activity provided access to DoD data. Colonel George T. Barido provided insightful comments on a draft of this article.