Reducing hospital readmissions is an increasing focus of health care quality improvement and cost reduction strategies (

1). Readmission rates for individuals with substance use disorders are relatively high (18%−26%) (

2). Having a substance use disorder is linked to greater complexity of care and hospital-related complications, longer stays, and greater likelihood of readmission, even when addiction treatment is not the reason for hospitalization (

3–

8). Furthermore, having a substance use disorder is associated with other health consequences and higher health services costs (

3,

9,

10). Among Medicaid enrollees, alcohol and drug use disorders have been shown to be among the top ten conditions with the greatest number of all-cause 30-day readmissions (

2). For Medicaid enrollees with a mental disorder, a comorbid substance use disorder diagnosis is known to be a major predictor of readmission (

11–

14).

This study examined whether Medicaid enrollees with a substance use disorder diagnosis who received targeted follow-up services (outpatient, intensive outpatient, or residential services) or MAT after an index hospital inpatient stay or residential detoxification had a lower likelihood of a behavioral health hospitalization or detoxification admission within 90 days, compared with individuals who did not receive follow-up services. Findings from this study should help to inform decisions about which services Medicaid and other payers should cover and how to improve care for enrollees.

Methods

Data

Data were from four component files of the 2008 Medicaid Analytic eXtract data set (

22): “personal summary” for beneficiary characteristics and enrollment status, “inpatient” for hospital services, “other therapy” for detoxification and follow-up services, and “prescription.” Data were linked by a unique enrollee identifier by state. Although data were from 2008, the relationship between follow-up services and postdischarge behavioral health readmissions was not expected to change over time. Analyses used deidentified data, and thus the study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Sample

The first (index) inpatient hospital admission with a substance use disorder diagnosis or residential detoxification admission between April 1 and September 1, 2008, was included for individuals ages 18–64 (N=30,439). Presence of a substance use disorder was determined by an ICD-9 diagnostic code for substance abuse or dependence in any position for an inpatient hospital admission or by a residential detoxification. All diagnoses (not just primary) were considered because among persons with serious co-occurring disorders, it is not always clear which will be designated as primary; furthermore, stigma may lead to a decision not to list substance use disorder diagnoses as primary. Noting a substance use disorder in a patient’s record is important given common medical complications and the need for addiction treatment services. Of the 30,439 admissions in the sample, 30.8% (N=9,378) had a substance use disorder as the primary diagnosis.

Excluded were individuals enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare or enrolled in managed care plans (because of likely incomplete claims data). Also excluded were individuals not continuously enrolled in Medicaid 90 days before and after their index admission and those who had substance use disorder diagnoses only of nicotine–tobacco use disorder, marijuana abuse, or hallucinogen abuse.

Data were included from ten states on the basis of a minimum number of index admissions and prevalence of follow-up services or MAT: Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Vermont. Thirty-seven states were excluded that had fewer than 650 index admissions, indicating no or few fee-for-service claims; three states were excluded in which none of the follow-up services were received by at least 5% of the patients who had index admissions. In the ten states that remained, an average of 82% of Medicaid enrollees were excluded because of their dual Medicaid-Medicare eligibility or participation in managed care plans (

23). [A table in an

online supplement to this article presents data on excluded individuals in each of the ten states.]

Variables

The outcome was time to a behavioral health admission in the 90 days after discharge from the index admission. For all follow-up services, eligible diagnoses were broadened to include both substance use disorders and mental disorders, given overlap in clinical needs and treatment approaches. A postdischarge behavioral health admission was thus defined as an inpatient admission with a primary diagnosis of a substance use or mental disorder or a residential detoxification admission. For readmission, only the primary diagnosis was used in order to focus on behavioral health admissions and to better indicate the effect of follow-up services on the substance use disorder itself.

Four key independent variables were created, each for the 14 days after discharge from the index admission. Receipt of follow-up treatment within a 14-day period indicates good clinical care by minimizing time outside treatment (

21). Current Procedural Terminology and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, place of service, and primary substance use or mental disorder diagnosis were used to identify residential behavioral health treatment, excluding detoxification; partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient; outpatient behavioral health services; and MAT, defined as a prescription fill of buprenorphine, disulfiram, acamprosate, or naltrexone or an HCPCS service code for methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone.

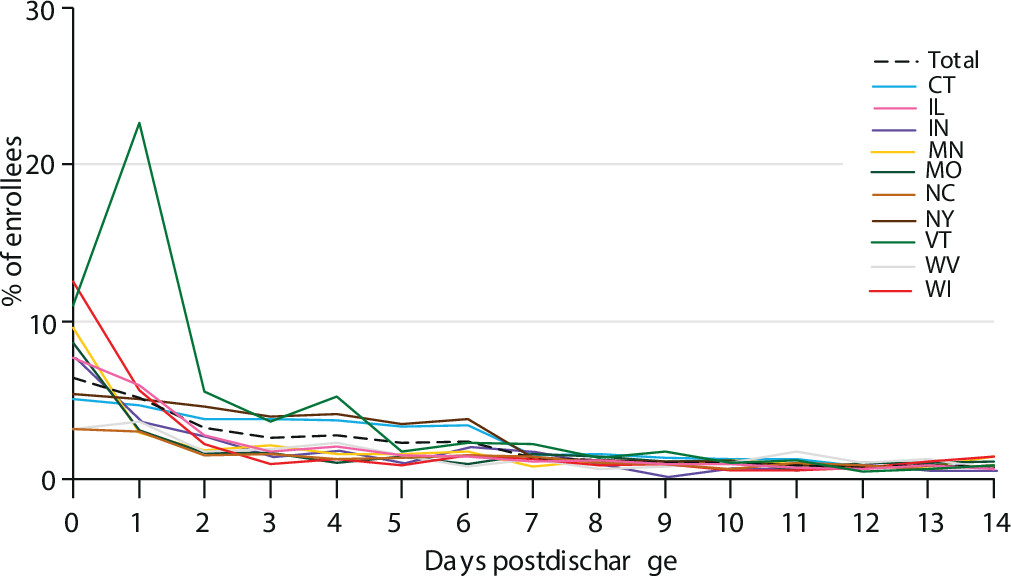

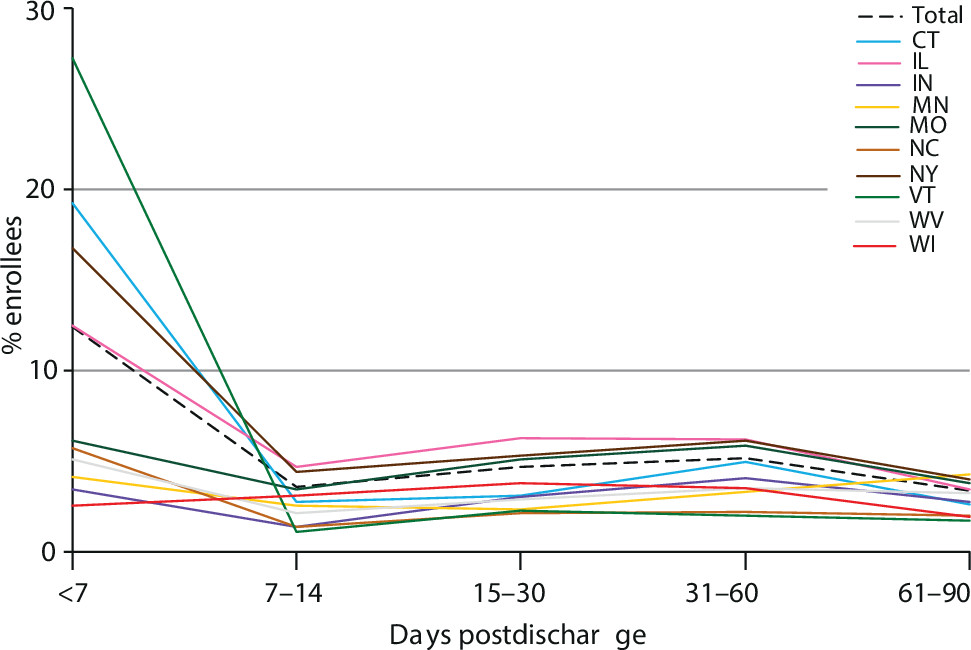

The number of days to the first follow-up service received within 14 days postdischarge was calculated. Service receipt could begin on the day of discharge (day 0). Because follow-up services could occur at any point in the 14-day window, the opportunity to observe a postdischarge behavioral health readmission varied. To address this, each follow-up service was coded as a series of time-varying independent variables from day 0 to day 14 for the survival analysis models. Once a follow-up service was received, the remainder of the 14 days was coded as having received that service. For the few patients who received two or three types of follow-up services (excluding MAT), an episode approach coded only the most intensive service received (residential, then intensive outpatient, then outpatient), starting on the first day of any services received.

Covariates were the basis of Medicaid eligibility (disability versus other), demographic factors (age, sex, and race-ethnicity), mental or general medical comorbidities at the index admission, substance use disorder characteristics (alcohol only or any opioid use disorder), index admission length of stay (days), and use of behavioral health services or MAT in the 90 days prior to the index admission.

Analyses

Available follow-up services varied by state, depending on Medicaid coverage in that state. Three models were run to account for each pattern of services: model 1, outpatient services and MAT in all ten states; model 2, outpatient, MAT, and intensive outpatient services in Connecticut, Indiana, Minnesota, Missouri, and Vermont only; and model 3, outpatient, MAT, intensive outpatient, and residential services in Connecticut, Minnesota, and Vermont only. Index admission was the unit of analysis.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate the effect of follow-up services and MAT on time to a behavioral health admission after discharge, with censoring at 90 days. Hazard ratios (HRs) are interpreted similarly to odds ratios, showing at any point in the 90 days after discharge whether an individual receiving the follow-up service within 14 days was more (HR >1) or less (HR <1) likely than an individual not receiving the service within 14 days to have a behavioral health admission. Models included all covariates. State was included as a fixed effect to account for differences in population, Medicaid eligibility, other Medicaid-covered services, and other unobserved variations. Analyses were conducted in SAS, version 9.3.

Discussion

For patients whose index admission record listed a substance use disorder diagnosis in any position, this analysis found strong support for the value of rapid follow-up with MAT or residential treatment services to reduce risk of a behavioral health admission in the 90 days after discharge. These results are consistent with studies showing an association between MAT and residential services and improved outcomes for patients with substance use disorders (

16,

18,

19). Most of the 30,439 patients in this study, however, received no follow-up service in the 14 days postdischarge.

Surprisingly, receipt of outpatient treatment services (and in one model, intensive outpatient services) was associated with an increased risk of readmission. On the surface this seems contradictory to expectations, but possible explanations arise. Patients’ discharge plans may have referred them to an inappropriate level of care—that is, outpatient treatment may have been insufficient to meet their needs for addiction treatment, but residential treatment may not have been recommended by the discharge team, may not have been readily available, or may not have been covered under Medicaid. Studies have shown that poor treatment matching leads to poorer substance use outcomes (

24–

26); thus readmission is more likely. Our findings suggest that no outpatient care is better than outpatient care (when analyses controlled for receipt of other services). Perhaps the presence of a referral to follow-up care or a return to preexisting treatment for substance use or mental disorders indicated a greater need for services following discharge. Furthermore, because residential services are scarce in some states or communities, people for whom residential treatment would have been appropriate might have been referred to outpatient or intensive outpatient services to receive any care. This study could not test these scenarios; the claims data did not include nuanced measures of severity or needed level of care.

The concept of follow-up services after discharge has clear face validity, but it may be difficult to show the benefit empirically. Challenges discussed next include access to postdischarge services, range in quality and coordination of inpatient and postdischarge services, and data concerns.

First, difficulties accessing behavioral health treatment arise for a variety of reasons (

27). Geographic and financial barriers are common, especially for more intensive levels of care. Fourteen days may be insufficient if individuals who are referred to care and intend to use it are unable to obtain appointments within this short window (

28,

29). A study of Medicaid enrollees discharged from a hospitalization for a mental disorder showed that the likelihood of follow-up treatment in a licensed mental health clinic increased by 16% to 22% when the investigators used a 30-day postdischarge follow-up window rather than a seven-day period (

30). However, a longer follow-up window also allows more time in which relapse might occur.

Second, the quality and coordination of postdischarge treatment may vary widely. For example, before a Medicaid quality improvement effort, inpatient providers in one state had low rates of communication with outpatient providers, as well as low rates of arranging for follow-up behavioral health care and referring individuals for general medical care (

30). Generally, claims data do not indicate whether communication occurred between inpatient and postdischarge clinicians, nor the level of attention paid to substance use disorders during the inpatient stay or whether the substance use disorder was addressed adequately or at all. If the major reason for hospitalization was a general medical condition, addiction may have been a side issue. Postdischarge services might not mitigate an initial lack of attention or inadequate attention to the individual’s substance use issues.

Third, the necessary omission from this study of states with Medicaid managed care, which likely carved out behavioral health services, resulted in the omission of data, and the states included in the study may not be representative. Replication that includes managed care and carve-out data would permit fuller confidence in these findings. However, compared with relatively unmanaged fee-for-service arrangements, managed care organizations may have different service arrays and may have procedures for preventing readmission; therefore, patterns of findings may differ. In addition, even in the ten states included in this study, which had the strongest data in terms of a minimum number of index admissions and prevalence of follow-up services or MAT, the analyses showed that few beneficiaries received any follow-up services. Individuals may have received services in settings that had block grant funding or from larger residential treatment programs that were ineligible for Medicaid payment based on the IMD exclusion (

31); such services would not be included in Medicaid claims. Even if a state offers a service, it may limit access to a subgroup of enrollees (for example, pregnant women or people with serious mental illness) (

32). The relatively few individuals who met study inclusion criteria may also reflect underidentification of persons with substance use disorders in claims data (

33).

Medicaid pays for a growing proportion of behavioral health services (

34), particularly under Affordable Care Act (ACA) health care reform (

31). However, states vary in Medicaid eligibility criteria, behavioral health services covered, spending on such services (

31,

35,

36), and contracting with specialty managed care organizations for behavioral health benefits. A true national study would have been ideal, but the vast variability among states in available services and financing approaches made this prohibitive.

Successful recovery from any diagnosis depends on many factors, such as the quality of care during the index admission, overall health status, demographic factors, and ability to purchase medications. Similarly, a complex variety of factors is associated with readmissions (

37). Systematic reviews of interventions to reduce 30-day general medical rehospitalization found that no single intervention is regularly associated with reduced risk (

38) and that effective interventions are complex and seek to enhance patient capacity to reliably access and engage in postdischarge care (

39). A recent project reduced 30-day readmission rates and increased MAT for patients admitted for alcohol dependence by implementing a discharge planning protocol (

40).

The analyses in this study relied on Medicaid claims data. Thus we were unable to determine, for instance, whether referrals were made at the time of discharge or whether an individual had difficulty accessing services postdischarge. Individuals dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare were excluded, which may have excluded some individuals with severe mental illness. Some states exclude certain services or populations from Medicaid, and thus resource availability may have played a role in these findings. Findings apply to persons who sought Medicaid-funded care. Services supported by other funding, such as block grants, may have been accessible to the enrollees, and thus the study may have underestimated receipt of follow-up services. This analysis controlled for disability as the basis of admission, but the definition of disability varies across states. Inclusion of an index admission allowed for a behavioral health diagnosis in any position, but inclusion of a readmission required a primary diagnosis of a behavioral health disorder. This approach excluded some readmissions but allowed for a focus on the impact of behavioral health services on readmissions that were likely related specifically to behavioral health problems. However, the approach may also have underestimated the number of readmissions by excluding those for which a behavioral health diagnosis was a key factor in readmission but for which the required primary diagnosis was not listed. This analysis did not examine the number of postdischarge services received or, if such services were received, other aspects of the follow-up care episode.

The generalizability of these findings may be limited. The exclusion criteria reduced the analytic sample to only ten states. Furthermore, the enrollees in those states who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare and those in managed care plans were excluded, and, on average, only 18% of Medicaid enrollees in the ten states were represented in the data. The findings thus are most applicable to persons who are in fee-for-service or other health plans that have low use of treatment management approaches or low use of additional supports to reduce readmissions. The findings are likely most applicable to persons who are low-income or otherwise eligible for Medicaid.

Future research could use alternative methods to examine questions raised by these limitations and discussed herein as challenges. In particular, research is needed to confirm—and if confirmed, to disentangle—the perplexing finding about outpatient follow-up care. The discussion suggests pathways to understanding the results, but further careful study is necessary. Furthermore, it is important to expand the populations to whom these findings might apply, such as by testing the hypotheses in Medicaid managed care populations, where data are available, and in privately insured populations.

Conclusions

In a time of change in the health care system, the question of how to reduce readmissions is important. Readmission of a large proportion of patients to hospitals within a short time frame may indicate inadequate quality of hospital care or lack of appropriate coordination of postdischarge care. Under the ACA financial penalties have been established for hospitals with excessive Medicare readmissions within 30 days after acute care hospitalizations for several diagnoses (

1,

41). Other payers likely will follow suit. However, concerns have risen about holding hospitals accountable when they cannot exert control over patient behavior and provider performance after acute care.

It is important to continue to examine readmissions and follow-up after treatment, given the heightened understanding of how substance use and mental disorders affect health and recovery, the likelihood of readmission, and the high stakes related to health care in this population. Future research should further investigate how MAT and residential treatment may be useful in improving outcomes after an inpatient stay and should also examine our counterintuitive results about outpatient care.

The findings highlight several policy implications. Most individuals had no follow-up services within the 14-day window. Services that are not received cannot improve outcomes. Policies implemented after 2008, the period of these admissions, including the ACA and federal parity, should increase access to behavioral health services under Medicaid. Furthermore, Medicaid programs should be encouraged to offer a range of substance use disorder treatment benefits to all Medicaid enrollees. This may require a renewed focus on how to best allocate scarce resources, especially for more expensive services, such as residential treatment. States should ensure that barriers to use of MAT are reduced—for example, by eliminating prior authorization requirements; by developing models, such as hub-and-spoke, to increase access to MAT in the community; or by specifically encouraging training for and adoption of MAT among Medicaid providers. Greater efforts are needed, such as focused discharge planning, follow-up phone calls, coordination with primary care providers, use of performance measures (for example, follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness [

42]), and better linkages between hospitals and specialty addiction treatment providers. Solutions that focus on benefit design should be combined with efforts targeted at referral processes to ensure that more individuals who are discharged from inpatient treatment receive appropriate and timely follow-up services.