More than a century ago, Kraepelin (

1) described dementia praecox as a progressively deteriorating condition. Longitudinal research published over the past 20 years has shown that recovery in schizophrenia is more common than previously thought (

2). Nonetheless, the view of schizophrenia as progressive and deteriorating is still commonplace in departments of psychiatry, state hospitals, and community mental health agencies, especially as applied to the third of individuals who have the most severe course (

3,

4). Buttressing this view is structural imaging research that shows thinning of the cortex for a proportion of individuals with schizophrenia over the course of their illness, indicating a significant loss of brain tissue (

5).

Antipsychotic medications have established efficacy (

6–

8) but also well-documented limitations: most individuals do not show a clinically significant antipsychotic response in the short term (

9), significant side effects that reduce quality of life and shorten the life span are common (

10–

13), little evidence has been found that supports long-term efficacy in reducing psychotic symptoms (

14), and there is also minimal evidence of improvement in negative symptoms (

15) or functional outcomes (

16).

Given that medications are a useful but limited tool for promoting recovery, there is a need for nonpharmacological approaches to this disorder. Psychotherapy has shown promise in this regard over the past 100 years. In 1909, Jung described an efficacious psychotherapeutic approach for a series of individuals who were given the diagnosis of dementia praecox (

17,

18). Nearly 50 years later, Beck (

19) reported successful treatment of an individual with chronic schizophrenia. Forty more years passed before several British clinicians and investigators developed a successful application of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for individuals with treatment-refractory schizophrenia (

20–

22). Meta-analyses have established CBT for schizophrenia as the most efficacious psychotherapy for the disorder (

23). However, a trial by Garety and colleagues (

24) found limitations of this approach, because individuals with schizophrenia who had a history of relapsing did not show any significant reduction in relapse compared with an active control group.

Our research group proposed that the psychotherapeutic approach to low-functioning individuals with schizophrenia could be greatly facilitated by pinpointing the specific psychological factors that interfere with recovery, particularly those that are not typically addressed by medications. We identified defeatist and asocial beliefs as factors that cross-sectionally (

25,

26) and longitudinally (

27) predict negative symptoms and poor functional outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia. On the basis of these empirical findings, we developed an alternative cognitive-behavioral approach that is heavily influenced by the principles of the recovery movement (

28,

29). Recovery-oriented cognitive therapy (CT-R) experientially neutralizes negative beliefs and attitudes while activating each individual’s latent positive attitudes to promote enduring adaptive living in the community (

30).

Because most individuals with low-functioning schizophrenia are profoundly isolated from interactions with others and have limited access to personal motivation to engage in activities, the treatment approach begins with various methods to engage and establish a connection (for example, listening to music, singing, dancing, and going for a walk). With an established engagement, the therapist works collaboratively with the individual to identify personal, meaningful, and valued aspirations for the future, such as obtaining a particular job, reconnecting with family, developing relationships with friends or lovers, and pursuing independent living in the community. The therapy then involves a series of nested success experiences along the path to the long-term ambition. The person is guided by the therapist to an adaptive cognitive shift regarding personal and social efficacy. Obstacles, such as low energy, hallucinations, delusions, disorganization, aggressive behavior, and substance use, are often blocks to recovery. The therapist uses the cognitive model to understand and help the individual attenuate the effects of these obstacles, thereby promoting progress (

31).

Previously, we reported the results of a randomized controlled trial showing the success of this therapeutic approach, compared with standard treatment in the community, for low-functioning outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (

32). At the end of treatment (18 months), individuals assigned to CT-R showed statistically significant improvement in global functioning, as well as statistically significant reductions in avolition-apathy and positive symptoms compared with individuals in the control condition (standard treatment in the community).

In this study, we addressed two additional questions from the randomized trial. First, does the experimental group maintain improvement during a six-month follow-up period? If differences between the two conditions are maintained after the therapy is withdrawn, this would support the durability of the skill acquisition and belief change to the person's life posttherapy. Second, because a significant proportion of individuals with chronic schizophrenia languish in state hospitals and other institutions (correctional or residential facilities), we addressed whether our novel approach works for the individuals in the sample with the most chronic illness.

Methods

The trial compared 18 months of CT-R plus standard treatment with standard treatment alone for 60 adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had low functioning, defined as at least moderate severity on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) global subscales or marked severity on one subscale. The mean±SD age of the sample was 38.4±11.6 years. The sample included 20 (33%) women and 39 (65%) African Americans. Participants were recruited from local community mental health agencies or a pool of names maintained at the University of Pennsylvania. These individuals completed two midtreatment assessments (six months and 12 months after baseline), an 18-month end-of-treatment assessment, and a 24-month follow-up assessment. Forty-six participants (CT-R, N=24; standard treatment, N=22) completed the follow-up assessment. Assessors were blind to treatment condition. All raters who were available to be tested (six of seven) performed no better than chance when asked to guess the participants’ condition (50 correct guesses and 53 incorrect guesses).

The CT-R condition focused on engagement within a goal-directed framework that included personalized treatment targets. Later sessions aimed to consolidate functional gains and prevent relapse. The standard treatment condition consisted minimally of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Most participants received services provided by local community mental health centers that could include case management, supportive counseling, day treatment services, housing services, peer support, and vocational rehabilitation.

The protocol and consent form were approved by two institutional review boards (the University of Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia). Each participant gave written informed consent before enrollment. Data collection occurred from January 2007 through May 2012. [A CONSORT diagram is presented in an online supplement to this article.]

Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted using hierarchal linear modeling (HLM). The primary outcome was global functioning (Global Assessment Scale) (GAS) (

33). An interviewer-scored assessment, the GAS is scored on a 100-point scale, with lower scores indicating poorer functioning. Secondary outcomes were negative symptoms (global rating for avolition-apathy on the SANS [

34]) and positive symptoms (total score on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms [SAPS] [

35]). Possible scores on the global rating for avolition-apathy range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Possible total scores on the SAPS range from 0 to 150, with higher scores indicating more severe positive symptoms. Treatment effects at follow-up were tested by examining treatment condition × 24-month interaction terms. To follow-up on these analyses, we computed nonparametric (Spearman’s rank) correlations between length of illness and (standardized residual) changes in GAS for those who received CT-R. In addition, t tests (paired sample) were conducted to determine whether and when significant changes in GAS emerged among participants with a longer length of illness (based on a median split) in the CT-R condition.

Results

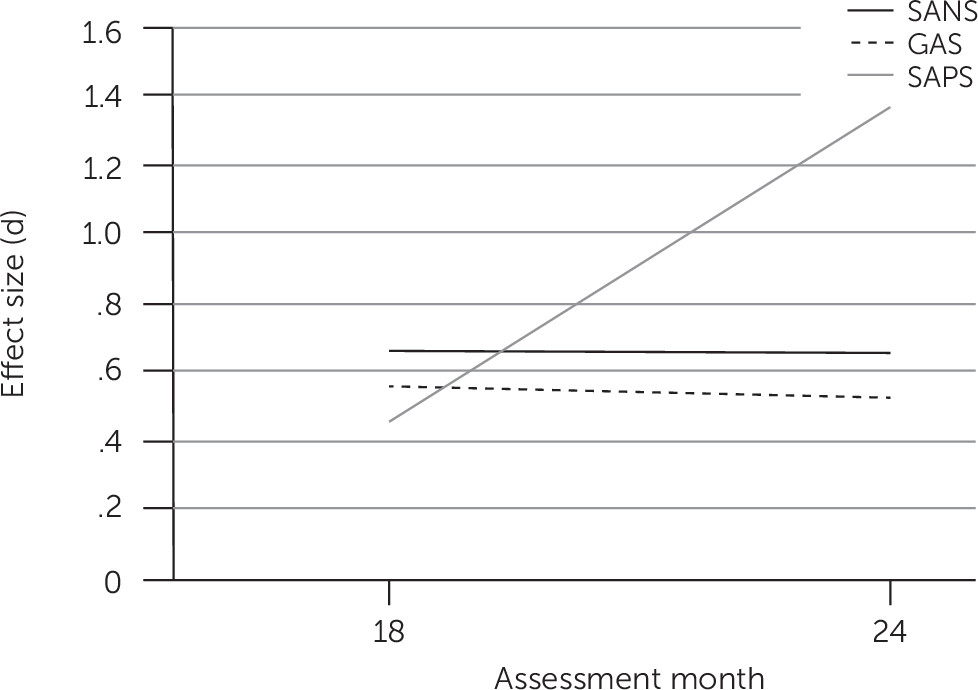

End-of-treatment and follow-up between-group effect sizes for the outcome variables are presented in

Figure 1. The treatment × 24-month interaction was statistically significant for global functioning (t=3.40, df=229, p<.01), indicating that global functioning in the CT-R group was superior to that in the standard treatment group at follow-up (adjusted mean±SE GAS scores, 63.14±4.64 versus 58.00±4.84; between-group d=.53). Similarly, the treatment × 24-month interaction was significant for negative (avolition-apathy) symptoms (t=–2.46, df=229, p<.05 [adjusted mean scores: CT-R, 1.63±.43; standard treatment, 2.17±.45; d=–.66]) and for positive symptoms (t=–3.52, df=228, p<.01 [adjusted mean scores, 14±3.61 versus 19.93±3.78, respectively; d=–1.36]).

Length of illness varied considerably in the sample, ranging from one to 40 years (mean=15.4±11.8). Also, although participants in the CT-R condition showed greater improvements in functional outcome overall, individual responses varied. HLM analyses predicting global functioning that included length of illness revealed a significant effect of chronicity (t=−2.93, df=219, p<.01), as well as a significant condition × length of illness ×18-month interaction (t=3.11, df=219, p<.01).

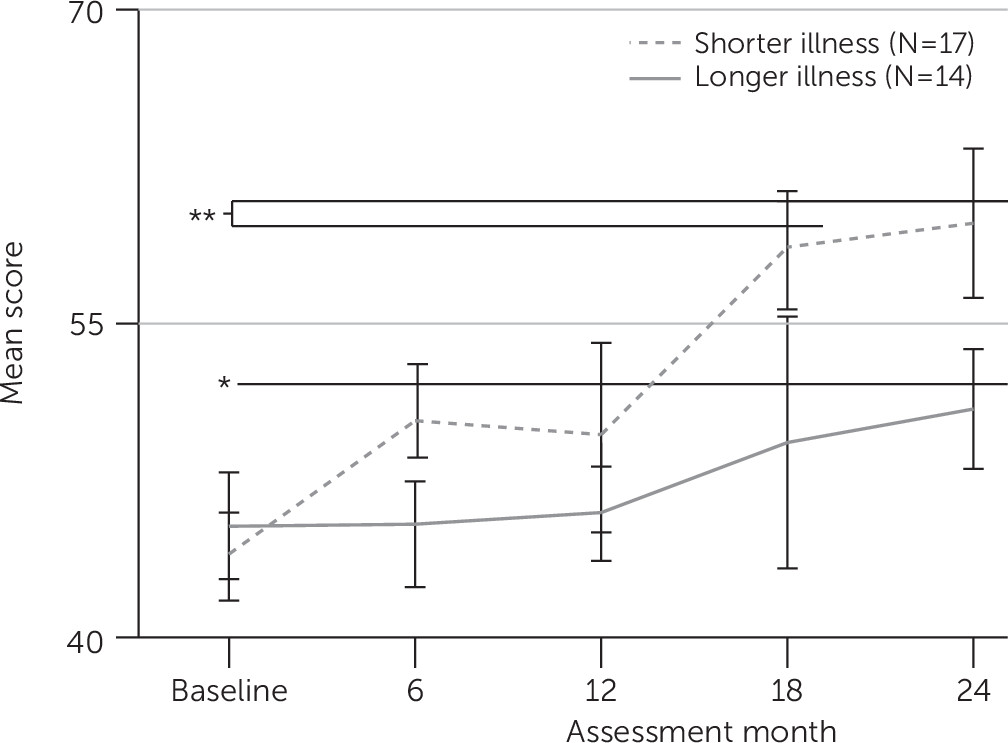

Twenty-four month follow-up analyses showed evidence that these results reflected delayed improvement in the CT-R condition for individuals with longer length of illness. Specifically, chronicity was significantly correlated with changes in GAS from baseline to six months (N=28 in CT-R condition with data available, r

s=–.33, p<.05), as well as from baseline to the end of the active treatment phase (18 months) (N=21, r

s=–.63, p<.01), but chronicity was not significantly correlated with changes in functioning at 12 months. Notably, length of illness was not significantly correlated with changes in GAS at any assessment point in the standard treatment group. In addition, those with a shorter length of illness (12 years or less) in the CT-R condition began to show evidence for improved functional outcome (compared with baseline) as early as six months (trend level, p=.07), with a statistically significant improvement evident by the end of active treatment (t=–3.62, df=8, p<.01), which was maintained at follow-up (24 months; t=–3.37, df=12, p<.01). In contrast, those with a longer length of illness (more than 12 years) did not show statistically significant or reliable improvement (from baseline) until the end of the follow-up phase (t=2.72, df=10, p<.05), because gains in this group were more modest at earlier assessment points. These findings are portrayed graphically in

Figure 2.

Discussion

Previously, we demonstrated that at the end of treatment individuals assigned to CT-R showed significantly greater improvement, compared with the standard treatment group, on global functioning, avolition-apathy symptoms, and positive symptoms (

32). The findings presented here show that these improvements over baseline were maintained across the follow-up period when therapy was withdrawn, supporting the notion that CT-R produces an enduring change in beliefs and skills that enables individuals to continue to maintain gains without their therapist. Given that negative symptoms have been linked to hospitalization rates (

36,

37), a promising direction for future research would be to determine whether CT-R’s amelioration of negative symptoms allows individuals to remain and participate in the community (

36).

In addition, we hypothesized that the group of patients with more entrenched disability, as indicated by a longer length of illness, would show a significant response to treatment if given sufficient time. Our findings supported this hypothesis, because the group with more chronic illness showed a delay in improvement in global functioning that achieved statistical significance compared with baseline only at the follow-up assessment. This finding suggests that even individuals with the most seemingly recalcitrant illness can improve and start to succeed at achieving their personally meaningful chosen goals.

The group with chronic illness had a number of characteristics that made their illness more refractory to treatment. Clinically, they appeared to be much more detached from the outside world and less reactive to psychosocial inputs—in particular, to talking—than the group with less chronic illness. In addition, isolation is motivated by clusters of negative expectancies and defeatist and asocial attitudes (

25,

26), which persons with chronic illness endorse to a greater degree than those with less chronic illness (

37). Finally, these individuals appear to be complacent when they are allowed to stay in a withdrawn mode, and they endorse less depression than those with less severe illness (

37).

Individuals with more chronic illness can be described as disengaged. The disengagement is characterized by a more global loss of interest in the outside world and future goals and a loss of engagement regarding basic psychological processes, such as attention, recall, and executive function. CT-R ameliorates these problems and enables individuals to become reengaged, which produces more energy and access to motivation, and opens up the opportunity to talk about aspirations for the future. The process of therapy reduces isolation, increases motivation, and overcomes obstacles, such as positive symptoms. Given that weekly sessions of CT-R can produce significant gains in functional outcome in the group with more chronic illness, more intensive treatment (delivered more than once weekly by a community treatment team or on a long-term inpatient unit) could increase the speed of response to treatment in this group, something we have observed in our implementation work.

This study illustrates how CT-R adds to the current treatment armamentarium for schizophrenia. CT-R compared favorably to psychiatric rehabilitation approaches, specifically cognitive remediation and social skills training. CT-R as a stand-alone treatment significantly and durably improved daily functioning, access to motivation, and positive symptoms. Cognitive remediation tends to show effects on functional outcomes only when embedded in a larger treatment package (

38), and it demonstrates modest effects on negative and positive symptoms (

38,

39). Social skills training has been shown to have an impact on social functioning and negative symptoms, but it affects positive symptoms to a minimal degree (

40). CT-R has powerful methods for engaging individuals in treatment and thus extends to more withdrawn individuals who typically refuse psychiatric rehabilitation. Accordingly, we present evidence in this report that individuals with the most chronic illness responded to CT-R, which is also an advance.

We hypothesized that the mechanism of change in daily functioning is a reduction in negative attitudes about performance and socializing and a corresponding strengthening of positive attitudes about self, others, and the future. We have evidence that experiences of success can directly contribute to improvements in cognitive variables and performance among individuals with schizophrenia who have the same level of severity as the group with more chronic illness (

41). We suggest, further, that the group with chronic illness requires more repetition of success, which accounts for their slower trajectory of improvement.

This study had limitations. Most notably, the sample was relatively small, limiting statistical power as well as confidence in the generalizability of the findings. The small sample made the study underpowered to determine the mechanism by which length of illness affected the outcome. It will be important to replicate these results, ideally in larger samples. Another limitation of the study is the use of GAS scores as a primary outcome measure. This scale is well validated and widely used, and the decision to use it is in line with the focus of CT-R, which emphasizes improving functioning rather than decreasing symptoms. Nevertheless, this scale arguably provides a relatively coarse index of the treatment goals of CT-R and other recovery-oriented interventions. Future work can address this limitation by incorporating cutting-edge measures of specific recovery outcomes (

42).

Conclusions

This study showed that the significant benefits of CT-R over standard treatment were maintained at follow-up and that the effect sizes were comparable to those observed at the end of treatment (

43), suggesting that treatment gains were well retained. Also, we found that length of illness predicted response to treatment, such that individuals with less chronicity who received CT-R began to show reliable improvements in functioning sooner (by 12 months), with the most prominent differences evident at the end of active treatment (18 months). Of note, those with greater chronicity showed reliable improvements, but they did so later (at 24 months), suggesting that clinicians should not give up on these individuals when it seems that they are not improving as quickly as hoped. More intensive treatment might quicken their recovery response. These findings add to our understanding of CT-R and specifically suggest that the therapeutic effects are durable and are present even among those with chronic illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the individuals who participated in this research and thereby made it possible. They also thank Gloria A. Huh, M.S.Ed., Dimitri Perivoliotis, Ph.D., Neal M. Stolar, M.D., Sally Riggs, Clin.Psy.D., Luke Schultz, Ph.D., Jarrod Reisweber, Psy.D., Nadine Chang, Ph.D., and Amy Wenzel, Ph.D., for assistance with the study and Marguerite Cruz, B.A., Robyn Himelstein, B.A., and Nina Bertolami, B.A., for assistance with the manuscript.