The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been established for more than a decade (

1). However, individuals with severe mental illness and PTSD have unique characteristics, such as a high sensitivity to stress, psychotic symptoms, and cognitive impairment, that may impede their participation in standard treatments. These specialized needs motivated the development of a CBT intervention for PTSD that is tailored for individuals with severe mental illness (CBT-P) (

2). In two randomized trials, the CBT-P intervention was shown to increase the likelihood of PTSD remission compared with usual services (

3) and an active comparator (

4). In the latter, more recent trial (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00494650), CBT-P was compared with a brief intervention that focused on breathing retraining and psychoeducation (BRF) (

5). The study reported here provided information about the comparative cost-effectiveness of these two interventions.

Dissemination in the public mental health system of PTSD interventions that are accessible to individuals with severe mental illness would constitute a critical step toward addressing the most severe consequences of trauma in this population. PTSD is a common consequence of trauma among individuals with severe mental illness, and studies have reported PTSD rates between 25% and 48% (

6), compared with an average estimated prevalence in the general population of 3.5% for past-year PTSD (

7). Trauma exposure among individuals with severe mental illness has been linked to more severe symptoms and distress, more impaired functioning, and higher use of acute care services (

8,

9). Moreover, among individuals with severe mental illness, PTSD is often not identified clinically and remains largely untreated (

5,

10,

11). However, dissemination of any new intervention within public mental health systems requires public investment in clinician training and system implementation, and public financing for such investments is limited. Consequently, the cost-effectiveness of PTSD treatment interventions designed for clients with severe mental illness in the public system should be examined.

We examined the comparative cost-effectiveness of CBT-P and BRF by using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which is the standard summary statistic used in cost-effectiveness analysis (

12). This statistic measured the additional mental health system costs per additional remission from PTSD achieved with the CBT-P intervention compared with the BRF intervention. The 12- to 16-session CBT-P intervention is delivered as an individual therapy, beginning with three sessions of breathing retraining for anxiety and education about trauma and PTSD, followed by nine to 13 sessions of cognitive restructuring (

2,

3). The three-session BRF intervention was designed to provide the same breathing retraining and educational components as the CBT-P intervention but without the cognitive restructuring (

5,

13). Because of the CBT-P intervention’s more complex provider training requirements and longer duration, its direct costs are greater than the greater direct costs for the BRF intervention. However, evidence that the CBT-P intervention was more effective than the BRF intervention for severe PTSD symptoms and resulted in improved functioning (

4) suggests that treatment with CBT-P may be associated with lower future costs for mental health care services, especially inpatient and emergency department care.

Methods

The randomized trial was conducted between April 2008 and July 2012 at three partial hospitalization programs and two outpatient mental health clinics in a public organization providing behavioral health care services located in central and northern New Jersey (

4). These programs predominantly serve publicly insured clients with severe mental illness. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Dartmouth College and Rutgers University. All statistical analyses were completed with Stata 14 software.

Participants

Study participants (N=201) met criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression, or bipolar disorder on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders. Participants also met the State of New Jersey definition of severe mental illness, which requires having a mental illness diagnosis, ongoing functional limitations in major life activities, and either multiple episodes of use of intensive psychiatric services or need of external supports to maintain independence from an institution. Finally, all participants met clinical criteria for a

DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD as verified by the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS) interview (schizophrenia version) and had currently severe PTSD symptoms (that is, a minimum CAPS total score of 65) (

14). Individuals who enrolled in the study were randomly assigned to either CBT-P (N=104) or BRF (N=97).

Assessment Timeline

Clinical assessments were conducted at baseline and immediately after treatment and then at follow-ups six and 12 months posttreatment. To avoid confounding the treatment intervention with the duration of time elapsed between the baseline and subsequent assessments, the follow-up assessment dates for the participants assigned to BRF were yoked to the dates for the posttreatment and follow-up assessments of those assigned to CBT-P. Eighteen individuals who completed no follow-up assessments—nine in the CBT-P group and nine in the BRF group—were excluded from the analysis; thus, data were analyzed for 183 participants.

Implementation Costs

To obtain certification in the CBT-P intervention, clinicians and their clinician supervisors attended a two-day onsite training conference led by two trainers. The first component of the CBT-P training conference focused on the BRF intervention. Training was followed by participation in a series of clinical supervision sessions to become certified in CBT-P and then by completion of one or two fidelity-rated practice cases (that is, a full course of CBT-P). During supervision sessions, an external clinician-consultant with expertise in the CBT-P intervention participated by phone. Both the onsite clinical supervisor and the external consultant provided tailored feedback and coaching to clinicians. Practice cases were audiotaped and then rated for fidelity by two external consultants (

15). If a clinician did not attain adequate fidelity on the first practice case, a second practice case was completed. Achievement of acceptable ratings required, on average, 17±7 hours of consultant time per clinician.

Intervention implementation costs included all personnel costs for CBT-P training as well as indirect costs for office space, utilities, and clinical program administration. Personnel cost estimates were obtained by multiplying labor hours by a mean hourly cost (

Table 1). Mean hourly personnel costs included estimated salary, fringe benefits, and payroll tax. An overhead rate obtained from reimbursement information reported in the provider organization’s accounting database was multiplied by intervention direct costs to obtain an indirect cost estimate, and then direct and indirect costs were summed.

On the basis of a review of the training schedule, we apportioned to the BRF intervention one-fourth the total personnel time spent in CBT-P training sessions, clinical supervision, and intervention fidelity ratings. Implementation costs were reported as costs per clinician. Implementation costs were also added as a depreciated expense to cost estimates for the delivery of other mental health care services by using straight-line depreciation over a ten-year period. We assumed that a full-time clinician would complete the CBT-P intervention with at least 25 clients per year and that the same clinician would complete the BRF intervention with at least 117 clients per year, on the basis of the ratio of 14 sessions for completion of the CBT-P intervention compared with three sessions for the BRF intervention.

Costs of Mental Health Care

Mental health care costs were estimated from the perspective of the public mental health system (that is, from the public payer perspective). They included the costs of all mental health inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient services and psychotropic medications received within the multisite provider organization plus the costs of psychiatric emergency department and psychiatric inpatient admissions at other sites, from randomization through the 12-month posttreatment completion. All study sites had access to a 24-hour hospital-based psychiatric emergency department program. Information on mental health services utilization, medications prescribed, and cost per service unit (

Table 1) came primarily from an administrative database maintained by the provider organization. These data were supplemented by clinician– and client–self-reported information on out-of-network psychiatric emergency department visits and inpatient admissions. These data were triangulated with the administrative data on inpatient and emergency department visits by using service dates and locations (

16). Information on the unit costs of psychotropic medications was from the 2010

Red Book (

17). Cost estimates were annualized by dividing the total costs over the entire data collection period by the number of days elapsed from study baseline to the 12-month posttreatment follow-up interview.

ICER

The ICER represents the addition to mental health costs (or savings) per additional PTSD remission resulting from receipt of the CBT-P intervention instead of the BRF intervention, or:

where AverageCOST is the mean cost per participant, and Pr(Remission) is the probability of a remission (that is, the participant no longer meets the clinical criteria for PTSD on the basis of the CAPS) at follow-up. Using an intent-to-treat design, we estimated generalized linear models of intervention effects on average mental health costs and the probability of remission. The cost model was specified by using a gamma distribution and a logarithmic link function, and the remission model was specified by using a binomial model and a logistic link function. Both models were adjusted for client marital status and study site, and the remission model was also adjusted for follow-up time point. Variances were adjusted for clustering at the individual client level (

18). To aid interpretation of a remission from PTSD in the denominator of the ICER, mean effect sizes were calculated for the association between a PTSD remission and three clinical rating scales: the CAPS total score, the Brief Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) score (

19), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score (

20).

Ten thousand bootstrap replications of the regressions and ICER calculations were used to produce 95% confidence interval (CI) bounds around ratio estimates. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which represent the proportions of bootstrap replications for which CBT-P was cost-effective compared with BRF at given willingness-to-pay values for a PTSD remission (

12), were also estimated. The CBT-P intervention could be more cost-effective, we reasoned, when delivered within partial hospitalization programs than when delivered within mental health outpatient clinics, because clients were already attending the partial hospitalization program for several hours and thus would be more consistently available to attend therapy. A sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the importance of program type by estimating ICERs separately for participants recruited from partial hospital programs and outpatient clinics.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

As shown in

Table 2, participants assigned to CBT-P were more likely to be currently or previously married than participants assigned to BRF (57% versus 39%, p=.014), and they were more likely to be living independently (74% versus 59%, p=.036).

Implementation Costs

Implementation costs were $6,190 per clinician (in 2010 dollars) for CBT-P and $1,853 per clinician for BRF. These totals can be apportioned to training (20%), supervision (58%), and fidelity rating (22%). Depreciated over a ten-year period, implementation expenses were $24.80 per client for the CBT-P intervention and $1.60 per client for the BRF intervention.

Mental Health Care Costs

Annual mean mental health care costs (in 2010 dollars) in the CBT-P intervention group ($25,539 per client) did not differ significantly from mean costs in the BRF intervention group ($29,530 per client) (

Table 3). In addition, no significant differences were found for any subcomponent of mental health services.

ICER

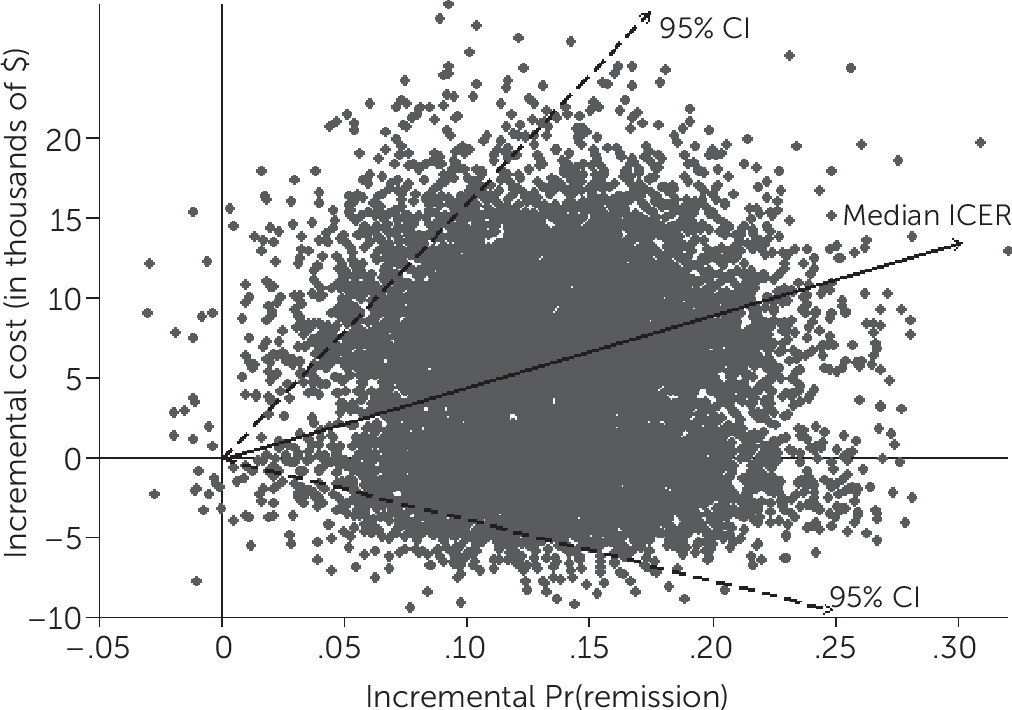

Figure 1 shows a scatterplot of the bootstrapped replications for the incremental effects of CBT-P versus BRF, along with the ICER median and 95% CI limits. The median ICER for all participants was $36,893 per additional PTSD remission yielded by CBT-P compared with BRF (CI=−$33,523 to $158,914). A remission from PTSD was associated with standardized mean effect sizes of −1.6 (CI=−1.7 to −1.4) for the CAPS total, .7 (CI=.6–.9) for the QOLI, and 1.0 (CI=.8–1.2) for the GAF. In 28% of the replications, predicted mean costs were lower in the CBT-P group than in the BRF group (that is, CBT-P was associated with net savings compared with BRF), and in .3% of replications, predicted effectiveness was greater in the BRF group than in the CBT-P group.

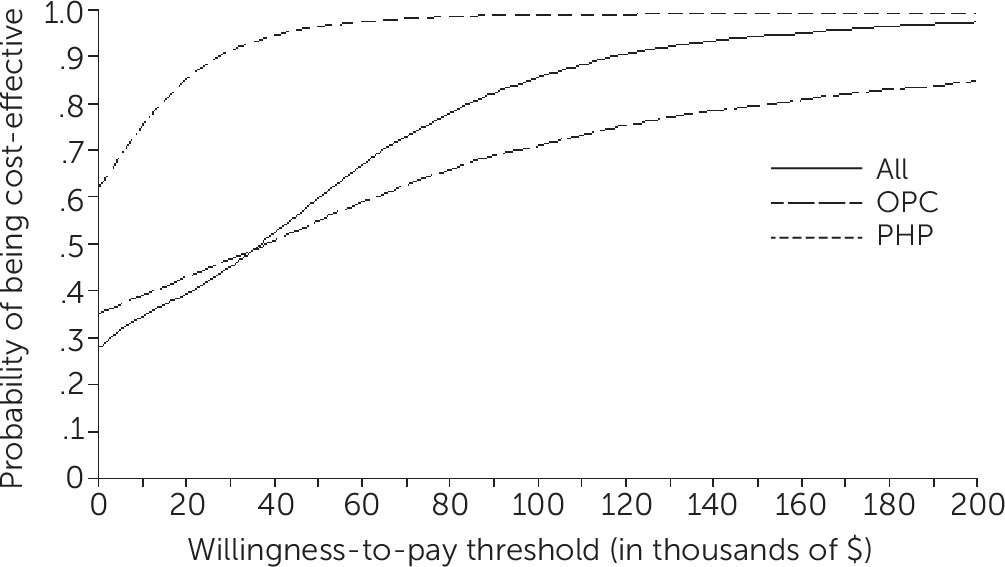

The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves in the overall sample, in outpatient clinics, and in partial hospitalization programs are shown in

Figure 2. A nonsignificant trend suggested that CBT-P was cost-effective at lower willingness-to-pay values in partial hospitalization programs (median ICER=$–7,740 per remission, CI=−$73,780 to $42,487) than in the outpatient clinics (median ICER=$33,277, CI=−$169,849 to $387,038).

Discussion

This is the first cost-effectiveness study of a PTSD intervention tailored for individuals with severe mental illness. It examined the comparative cost-effectiveness of the CBT-P intervention in obtaining remissions from PTSD compared with an active comparator, the BRF intervention. The median ICER indicated that receipt of the CBT-P intervention resulted in an additional $36,893 in additional mental health care costs (in 2010 dollars) per additional PTSD remission compared with the BRF intervention. A remission from PTSD corresponded to a large reduction in average PTSD symptom severity (−1.6) and moderate or large improvements in average subjective quality of life (.7) and global functioning (1.0). Also, training a clinician to deliver the CBT-P intervention cost more than did training a clinician to deliver the BRF intervention ($6,190 versus $1,853) and required more time.

Given the wide confidence interval for the ICER and the fact that the monetary value of a remission is unknown, we could not determine whether the additional costs of CBT-P are justified by an improvement in remissions. Findings from the clinical trial comparing the two interventions indicated that the CBT-P intervention was moderately more effective than the BRF intervention (Cohen’s d=–.26 for a CAPS PTSD diagnosis at follow-up) (

4). The results of the study reported here indicate that in the process of obtaining this clinical benefit, mental health costs are likely to be greater than they would have been in the absence of the intervention. In this study, CBT-P was in most bootstrap replications (72%) associated with more remissions from PTSD and higher costs. However, in just over a quarter of the replications (28%), the CBT-P intervention was both more effective and more cost-saving compared with the BRF intervention, suggesting that CBT-P could in some cases result in better outcomes at lower cost. Although we could not establish a more definite result, this first cost-effectiveness study of this clinical population establishes a benchmark that can be compared with results of future studies.

Other results suggest nuances for future dissemination of CBT-P and BRF interventions in public mental health systems. First, a sensitivity analysis suggested that the CBT-P intervention might be more cost-effective when offered in partial hospital programs compared with outpatient clinics, presumably because attendance at CBT-P was better in the former settings (

4). As reported previously (

4), the proportion of clients who completed at least six CBT-P sessions was greater among clients at the three partial hospitalization program sites (68%, 85%, and 100%, respectively) than among clients at the two outpatient clinic sites (47% and 49%, respectively).

Second, individuals in the BRF intervention group had a remission rate of 24% at six months posttreatment (

4), which is double the 12% rate observed among individuals in usual care during a previous trial of the CBT-P intervention in a similar clinical sample (

3). This raises the question of whether the BRF intervention is itself an effective intervention and suggests the possibility of stepped PTSD treatment (

21,

22), wherein the BRF intervention would be offered as a first-line therapy followed by CBT-P for individuals whose PTSD symptoms do not remit. This stepped approach might also be more efficient to implement because of BRF’s lower implementation costs and shorter treatment duration (three sessions for BRF versus 12 to 16 sessions for CBT-P). Given these differences, an equal investment in training a clinician to provide the BRF intervention rather than the CBT-P intervention could result in a greater overall number of remissions and might not differentially influence mental health care costs.

This study had several limitations. A potential limitation is that the study might have lacked adequate statistical power to detect significant group differences in mental health care costs. However, it is also possible that a significant effect on cost would not have been found even in a much larger sample. Although mean costs in the CBT-P group were nearly $4,000 greater than in the BRF group, bootstrap replications revealed that CBT-P resulted in net savings for a minority of clients. A second limitation is that no data were collected on the costs of out-of-network outpatient mental health care, general medical care, criminal activities, arrests and incarcerations, public housing, and other public-sector social services, which limits the generalizability of this study’s findings. In addition, positive effects of the CBT-P intervention on clients’ global functioning (

4) might be associated with other public benefits, such as improvements in labor market earnings or reductions of disability payments, which were not captured. Third, an unanswered question is whether the BRF intervention is more effective than usual care. If it is not, the status quo of PTSD treatment might be the best policy. However, results from this trial showing reductions in PTSD severity over time in the BRF treatment group were suggestive of an improvement over usual care (

4). Finally, we caution that this study’s results should not be interpreted as generalizing to populations other than individuals with serious mental illness and PTSD. The CBT-P intervention was tailored for this population, and the effects of CBT-P may be altogether different in other populations.

Conclusions

In a sample of adults with severe mental illness who had co-occurring severe PTSD, the tailored CBT-P intervention was not found to be significantly more cost-effective than the BRF intervention, although wide CIs around cost-effectiveness ratios suggest that CBT-P might be cost-saving for a subset of clients. A nonsignificant trend in the data also suggested that the CBT-P intervention might be more cost-effective when implemented in partial hospitalization programs compared with outpatient clinics. Although the BRF intervention was less effective overall, its lesser implementation costs and training requirements and shorter treatment duration suggest that dissemination of the BRF intervention alone or as the first step of stepped therapy using the CBT-P intervention could be an efficient strategy for improving access to treatment for PTSD in public mental health systems. More evidence regarding the BRF intervention’s effectiveness is needed to address this question.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals who contributed to this project: Rosemarie Rosati, L.S.W., Stephanie Marcello Duva, Ph.D., Christopher Kosseff, M.S., Karen Somers, M.A., M.B.A., Zygmond Gray, L.C.S.W., Avis Scott, L.C.S.W., John Markey, L.P.C., Rena Gitlitz, L.C.S.W., John Swanson, L.C.S.W., Rosemarie Wolfe, M.S., and Rachel Fite, Ph.D. They also thank the clinicians at Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care and the clients who participated in this study.