Recent research indicated that adults with serious psychological distress reported reduced access to and use of health care compared with adults without serious psychological distress (

1). This pattern was exacerbated by the Great Recession of 2008–2009, which likely caused adults with serious psychological distress to lose access to health care and lack money for needed prescription medications (

1,

2). This alarming disparity for adults with serious psychological distress warrants further examination to determine differences across race-ethnicity and gender.

Disparities in health care utilization by race-ethnicity are a persistent challenge in the United States (

3). Non-Hispanic blacks (blacks) and Hispanics have faced increased barriers to care and lower utilization compared with non-Hispanic whites (whites) (

3). Blacks were found to have fewer physician contacts, and Hispanic women used fewer hospital or outpatient services (

3). Studies have noted disparities in psychotropic medication prescribing by race-ethnicity in the home health care population (

4,

5). Among diabetic patients, significant disparities were found by race in health outcomes and quality of care (

6). Disparities in access to care have been reported among adults using mental health services (

7).

Serious psychological distress is a validated measure of mental health within a community. Although it is not a diagnosis of a particular disorder, serious psychological distress covaries with serious mental illness and is associated with the poor outcomes found among adults with mental illness (

8,

9). The few studies of disparities among adults with serious psychological distress found higher medical expenditures and increased use of outpatient, inpatient, and emergency care compared with adults without serious psychological distress (

8,

9).

A closer look at disparities in health care utilization by race-ethnicity and gender is needed, given the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has potential to improve access and utilization among disadvantaged groups through expanded Medicaid coverage. This study used national survey data to provide baseline patterns of access and utilization among adults with serious psychological distress by race-ethnicity and gender. Our hypothesis was that among adults with serious psychological distress, race-ethnicity and gender predict poor health care utilization, including insufficient money for health care and delays in care. We also examined whether health care access and utilization varied by health coverage type and race-ethnicity across survey years that included the Great Recession of 2008–2009 and ACA implementation.

Results

The analytic sample included 8,940 adults with serious psychological distress; the weighted sample represented 10,751,275 adults nationwide. Approximately 50.3% of the overall sample was between the ages of 18 and 44 (mean±SD age=43.9±12.4). Most respondents were women (59.4%, CI=58.1%−60.8%) and white (66.8%, CI=65.3%−68.3%). Of the sample, 10.4% (CI=9.5%−11.3%) had at least a college education, and 33.9% (CI=32.6%−35.3%) had an annual family income below the federal poverty line.

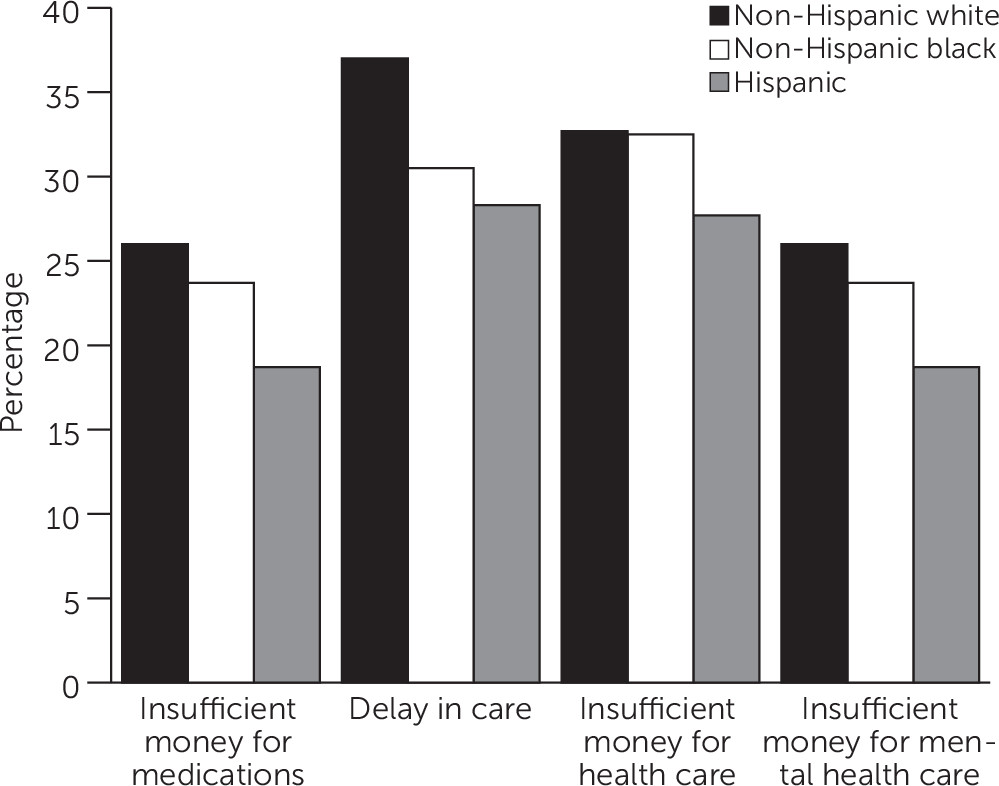

Hispanics were more likely to be represented in the younger (18–44) age category (58.7%, CI=55.4%−62.0%). [A table summarizing characteristics of the sample is available online as a supplement to this article.] Among Hispanic adults, the greatest proportion (39.4%, CI=36.2%−42.6%) were in the group with lowest income (<100% of the FPL). Whites and adults of other races-ethnicities were more likely than Hispanics or blacks to have private insurance, and Hispanics were more likely than the other groups to report no coverage. Blacks were more likely than the other groups to report Medicaid and Medicaid plus private coverage. Whites were more likely than the other racial-ethnic groups to report poor health care utilization, including insufficient money for medications, for mental health counseling, and for health care; delays in care; and change in the usual place of health care.

In multivariate models, women were at greater risk than men of reporting insufficient money for medications, delays in care, insufficient money for health care, visiting a doctor ten or more times, changing the usual place of care, and insufficient money for mental health care [see online supplement]. Compared with the highest income group (≥400% of the FPL), all other income groups had poorer utilization. Compared with adults living in the Northeast, adults in the West were at significantly greater risk of insufficient money for medications, delays in care, and insufficient money for health care; they were also less likely to have seen a mental health care provider, but the finding was not significant (p=.06). Compared with adults living in the Northeast, adults in the South were at greater risk of delays in care. Compared with black adults, white adults were at increased risk of having insufficient money for medications, delays in health care, and having insufficient money for mental health care, and they were more likely to have seen a mental health provider in the past 12 months. Compared with black adults, Hispanic adults had lower odds of having insufficient money for medications and for health and mental health care.

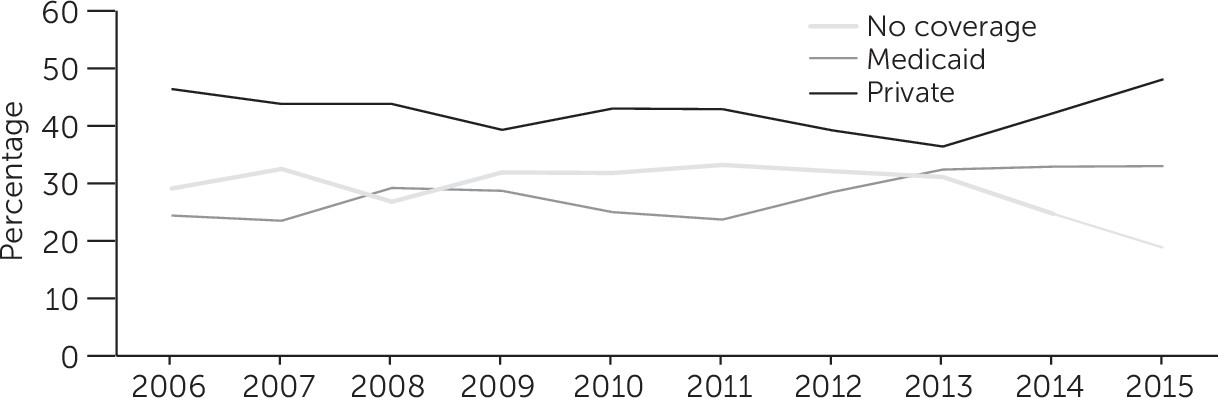

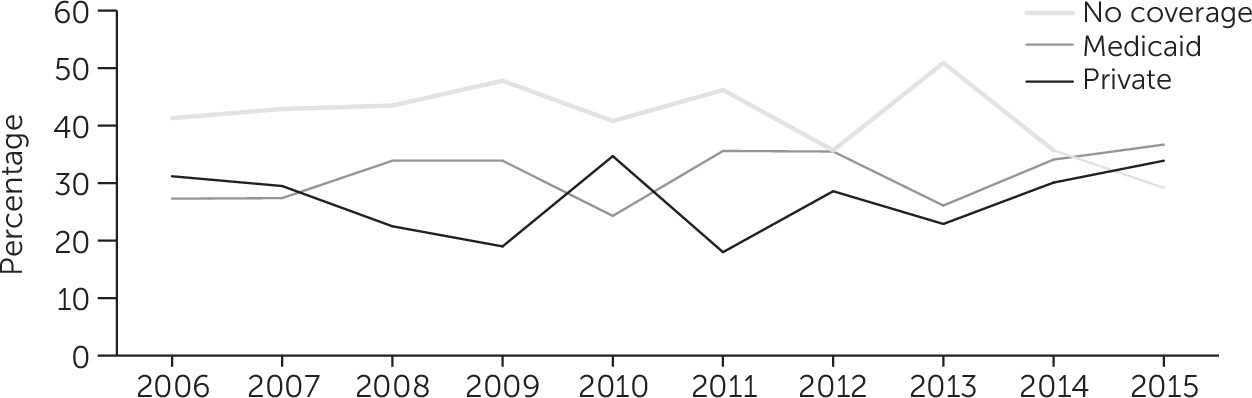

Using Rao Scott chi-square tests, we analyzed data for Hispanic, white, and black adults with serious psychological distress across 2006–2015 by insurance coverage (no coverage, private coverage, and Medicaid) (data not shown). We found significant changes in health coverage type across survey years for white and black adults (p<.01), and a trend toward significance for Hispanic adults (p=.08). A multinomial regression with health coverage type as the outcome and survey year, race-ethnicity, and an interaction term between race-ethnicity and survey year as predictors showed that compared with whites, Hispanics and blacks experienced significant changes in health coverage type. The regression also showed a significant decreasing linear trend during that time in having no coverage. We included an indicator variable for 2009 onwards to measure effects after the Great Recession of 2008–2009, and this showed that there had been an increase in the proportion of adults with serious psychological distress who had no health coverage (p<.001).

Among white, black, and Hispanic adults with serious psychological distress, the proportion not covered by insurance increased from 2006 to 2011 (

Figures 1,

2, and

3). For all groups, the proportion not covered decreased from 2012 to 2015, with corresponding increases in the proportion with private insurance and Medicaid. In 2015, whites had a greater proportion with private insurance compared with blacks and Hispanics, and blacks were more likely than whites and Hispanics to have Medicaid coverage.

The proportion of adults with serious psychological distress who had no coverage and the proportion who had Medicaid and private insurance varied by region (p<.001). The proportion of adults with serious psychological distress without health coverage was greatest in the South (39%, CI=37.7%−42.1%). The proportion of adults with serious psychological distress with private health coverage (38.1%, CI=33.4%−42.7%) and Medicaid (41.7%, CI=38.2%−45.2%) were greatest the Northeast. Race-ethnicity also varied significantly by region (p<.001). The proportion of Hispanics with serious psychological distress was largest in the Northeast, and the proportions of white and black adults with serious psychological distress were largest in the South [see online supplement].

The bivariate results shown in

Figure 4 display the prevalence of health care utilization indicators among various racial-ethnic groups. Those listed were found to be significantly associated with race-ethnicity.

Discussion

The study’s major finding was that among adults with serious psychological distress, whites were significantly more likely than blacks to experience barriers to utilizing health care, including having insufficient money for needed medications and mental health care and experiencing delays in care. Our findings are surprising in light of numerous studies demonstrating disparities in health care utilization among adults in racial-ethnic minority groups (

3–

7). In particular, black and Hispanic adults have historically fared worse than white adults, who disproportionately use private coverage (

24). Historically, Hispanics have reported delays in care and were likely to forgo needed health care (

24). As recently as 2010, blacks reported worse access to and quality of care compared with whites (

24). However, with implementation of the ACA, these historical black-white disparities appear to have improved (

25,

26). Our findings demonstrate that improvements in black-white disparities in health care utilization have also occurred among adults with serious psychological distress, although disparities still exist by gender. We found that women showed decreased health care utilization among women compared with men, validating earlier studies demonstrating that women were more likely than men to experience delays in care (

27,

28).

Disparities in utilization among white adults with serious psychological distress is particularly concerning in light of recent reports showing an increase in serious psychological distress and a reversal of decades of increased longevity (

27–

29). Researchers have observed decreased longevity from poor mental health among both white women and white men (

29–

31). Lack of health coverage has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of mortality (

24). Insufficient money to see a mental health provider may have important health implications for adults with serious psychological distress because of the strong association of serious psychological distress with several chronic health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, COPD, and diabetes, and with limitations in the ability to work and activities of daily living (

29,

31). Future research could examine access to and utilization of health care in the middle-aged population because the decrease in longevity affects that group.

Among adults with serious psychological distress, disparities in health care utilization among whites, compared with other racial-ethnic groups, suggest that explanations for decreased longevity among whites in the past decade are related to the structure of the health care system. When individuals have insufficient money to treat serious psychological distress, a cascade of challenges could occur, including difficulties with employment (

13,

14). Job market volatility and periods of unemployment seem to play a role in poor health care utilization among adults with serious psychological distress from all racial-ethnic groups. A recent study demonstrated that adults with serious psychological distress had difficulty recovering their health care access and utilization after the Great Recession of 2008–2009 (

1). It is possible to imagine a scenario in which lack of access to health care resulting from employment loss begins a downward spiral, with no coverage available to treat worsening psychological distress (

18,

32,

33). We found that compared with having private insurance, having no coverage tended to predict poor utilization and that having Medicaid coverage appeared to predict better utilization.

The Great Recession of 2008–2009 affected health coverage for white, black, and Hispanic adults with serious psychological distress for several years after the event. With recovery and return to fuller employment, white adults with serious psychological distress may have regained private insurance coverage. However, during periods of high unemployment, they may have been at a disadvantage in not having the stability offered by Medicaid coverage, which in our study was associated with better utilization. More important, having private coverage may put them at risk of having no coverage should there be another economic recession (

34).

Gaps in employment and loss of private coverage may explain racial-ethnic disparities in health care utilization among adults with serious psychological distress. During times of economic recession, the roller coaster associated with loss of employment and the health coverage it provides could contribute to perceptions among white adults of barriers to care. The Medicaid expansion that accompanied ACA implementation has not been adopted by all states. In states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, black adults have made tremendous gains in access to care (

24). Advancements in coverage, particularly among groups disproportionately affected by economic recessions, suggest that the Medicaid expansion offers an appropriate safety net to preserve access to health care (

35).

We observed a paradox among Hispanic adults with serious psychological distress. Compared with white adults with serious psychological distress, they were more likely to report having no coverage but less likely to report poor utilization. This finding suggests the presence of factors related to immigration and health care use that require further analysis. Hispanic adults may be more likely to underreport health care access and utilization because of concerns about documented citizenship (

36,

37). Whites were more likely than other racial-ethnic groups to report having seen a mental health provider in the past 12 months; however, underreporting by other racial-ethnic groups because of stigma regarding serious psychological distress may have played a role. Of note, among adults with serious psychological distress, whites were no more likely than blacks to report having visited a doctor ten or more times. This finding contrasts with results of previous research showing that white adults were disproportionately heavy utilizers of health care (

38).

We caution that our preliminary findings were based on cross-sectional data, which prohibits causal inference. We did not test variables about the economy; for example, we did not conduct a month-by-month examination of the Great Recession or of ACA implementation, nor did we examine differences in private insurance plans. In addition, we could not examine a broader range of general medical conditions and racial-ethnic subgroups. A strength of the study was its use of the NHIS, which provides data from a national sample.