Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among all persons and the third leading cause of death among persons between the ages of 20 and 50 (

1). The fatality rate of suicide attempts varies substantially depending on means: 85% of attempts involving firearms result in death, compared with 69% involving suffocation, 2% involving poisoning and overdose, and 2% involving other means (

2). Although homicide and accidental shootings receive the most attention in the news media and in policy contexts, 63% of firearm injuries in the United States are self-inflicted (

3). Approximately 50% of all suicide deaths occur by firearm, 20% by suffocation or hanging, 20% by medication or chemical poisoning, and 10% by other methods (including jumping, self-injury with a sharp object, and drowning) (

2,

4).

The health care setting is recognized as an opportune setting for prevention of suicide (

4–

6), and for that reason—as well as a recent rise in suicide mortality (

7)—the Joint Commission recommends that providers in multiple health care settings increase suicide screening and conduct means restriction counseling for at-risk patients (

8). Means restriction counseling occurs when a general or behavioral health provider advises a patient, the family of a patient, or both to voluntarily remove access to objects that may be used for suicide, such as firearms, potentially lethal medications, sharp objects, and suffocation instruments (

9). When patients are identified in primary care as being at risk of suicide, typically during depression screening, means restriction counseling is a highly recommended risk management practice (

10). Patients and family members are usually receptive to means restriction counseling when a suicide risk is identified (

11,

12).

Despite these recommendations, provider surveys indicate that means restriction counseling delivery rates are low. Only 4% to 14% of emergency department physicians and 22% of psychologists discuss means restriction following a suicide attempt (

13,

14). That is concerning because 10% of patients who make nonfatal suicide attempts go on to die by suicide, and 25% have a subsequent nonfatal attempt (

15,

16). It has been suggested that rates of means restriction counseling may be low because providers do not believe in its effectiveness (

17), and they focus instead on mitigating intent. Suicidal intent is impulsive or not planned in advance in 82% of attempts (

18) and is estimated to last from five minutes to one hour (

19,

20). Therefore, the opportunity for providers to intervene effectively when suicide intention arises is dependent on patients accessing care during times of crisis. Means restriction counseling is a promising approach to save lives by creating a barrier to the impulsive intent of self-harm, which is independent of the patient’s voluntarily accessing care. Effective and efficient means restriction counseling depends on reliably identifying which patients to screen for suicide to determine those who would benefit.

Identifying patients at risk of suicide in general medical settings is challenging. Recent evidence suggests that relying solely on pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses or an expectation that patients will spontaneously volunteer risk symptoms is problematic (

10,

21). For example, of people who die by suicide, 57% of veterans (

22) and 50% of civilians (

4) had no recorded history of a mental disorder at the time of their death. Yet 45% of patients seek medical care within one month prior to suicide death (

4,

23). These findings highlight a gap in the current implementation of suicide risk detection in general medical settings, which typically occurs only following a positive depression screen.

Identifying general medical disorders that may be significant risk factors for suicide is important to inform suicide risk detection. Using the same data source as this study, our group conducted one of the largest U.S.-based studies examining the association of common general medical disorders with suicide (

24). Findings indicated particularly high odds ratios for traumatic brain injury (TBI), sleep disorders, and HIV/AIDs after the analyses controlled for mental and substance use disorders. This study builds on our previous work to examine the association of general medical disorders and mental disorders with specific means of suicide.

The objectives of this study were to identify patients who are most at risk of suicide death by firearm compared with other means by using data that are readily available to health care providers. We compared demographic and clinical variables among patients who died by firearm versus other means of suicide with those of matched patients who did not die by suicide (control group) . Understanding this constellation of risk factors has the potential to inform suicide risk assessment and prevention practices, including means restriction counseling.

Methods

Sample, Settings, and Data

In 2016, we conducted a case-control study of 2,674 adult and adolescent patients who died by suicide and 267,400 patients who did not die by suicide. Patients were members of eight learning health care systems within the Mental Health Research Network (

25). The network sites in this study included Henry Ford Health System (Michigan), HealthPartners (Minnesota), Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (Massachusetts), and Kaiser Permanente health systems in Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington. Each site offers integrated general medical and mental health care services, including individual and group therapy, intensive outpatient programs, and psychiatric medication management. These sites cover a population area of more than three million, with demographic characteristics mirroring the surrounding urban and suburban geographic areas. Detailed population demographic and health plan characteristics stratified by site are available at the Mental Health Research Network Web site (hcsrn.org/mhrn/en/Tools%20&%20Materials/MHRNResources/).

As a control, a random sample of 100 patients were matched to each of the 2,674 suicide cases by site and year of death. The date of suicide death was considered as the index date for cases, and their matched counterparts were assigned the same index date. All participants were continuously enrolled in a health plan for at least 10 months during the year prior to the index date, which allows for a small disenrollment gap during the month of death. Each site received institutional review board approval.

All data were extracted from a Virtual Data Warehouse that includes electronic health record and insurance claims data (

26–

28). The Virtual Data Warehouse is a set of variables with mutually agreed-upon validated definitions across each site to facilitate multisite research projects across the network. This allows each site to retain its own private patient general medical and mental health record data yet overcome the challenge of data harmonization inherent in multisite research. There are routine data quality verifications to ensure that the standard variables are defined similarly across systems. Death data are verified with mortality records from national, state, and local public health organizations by Social Security Number or through a combination of the patient’s name, birthdate, and demographic profile.

To identify patients who died by suicide and the method of suicide, we used

ICD-10 codes to define firearm suicide (X72–X74) and suicide by other means (X60–X71, X75–X84, and Y87.0) (

29). Other means included all means other than firearm, with poisoning and hanging or suffocation being the most common.

ICD-9 codes were captured from health system encounters (inpatient and outpatient) for all study patients to ascertain diagnoses that were current within the year prior to the date of death (

30). Diagnoses were extracted for 13 major mental and substance use disorders and 21 general medical disorders. Demographic information on age and sex were available from the data warehouse, and neighborhood income and education were estimated by using geocoded addresses and census block data.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out by using SAS, version 9.4. Descriptive statistics summarized demographic variables, mental disorders, and general medical disorders for cases of suicide, grouped by means of suicide death (firearms or other means). To determine the association of mental disorders and general medical disorders with suicide death, we used a series of logistic regressions to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals. Four separate models were analyzed to determine the relative contributions of demographic and clinical variables to the odds of suicide by firearm or other means. Using logistic regression, multivariable models were fit for cases of suicide by firearm versus the control group (model 1) and cases of suicide by other means versus the control group (model 2). Covariates for models 1 and 2 included age, sex, and disorder (for example, diabetes). For models 1 and 2, separate models were run for each of the 35 mental and general medical disorders, and the odds ratios for each model are reported.

To evaluate the difference in association between suicide and individual disorders among cases of suicide by firearm versus other means, model 3 included a gun × disorder interaction term. The interaction p value detects whether there were statistically significant differences between the firearm and other-means groups in the odds for each disorder. Because of large gender differences in the means of suicide, we isolated the impact of gender and comorbidity by using an interaction of comorbidity × gender in a fourth logistic regression model. To determine comorbidity, we defined a variable for comorbidity as the presence of zero, one, or two of the following general medical disorders: asthma, back pain, TBI, cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, epilepsy, migraine, multiple sclerosis, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, psychogenic pain, renal disorders, and stroke. To isolate the effect of comorbidity involving general medical disorders from the effect of having a mental disorder, we defined a binary covariate for presence of any mental disorder, which was included only in model 4. Additionally, we included age, education, and income as covariates in the model. Separate models were run for the firearm and other-means groups. We were primarily interested in the odds ratios associated with various levels of comorbidity (0, 1, and ≥2 general medical disorders) within each gender.

Results

Our sample included 2,674 cases of suicide death, 1,298 (49%) by firearm and 1,376 (51%) by other means (

Table 1). Men (77%, N=2,063) accounted for most cases of suicide death, with a higher proportion of men among cases involving a firearm (89%, N=1,155) versus other means (66%, N=908). Most cases (61%, N=1,631) involved at least one mental disorder, with the highest prevalence for alcohol use, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders, respectively (data not shown). This rate is higher compared with the results of previous studies conducted by the network, which reported that 50% of suicide cases involved a mental disorder, because of the inclusion of dementia and tobacco use in the definition of mental disorder. A substantial portion of cases did not involve having had a psychiatric disorder diagnosed in the year prior to suicide death (45% [N=579] of suicides by firearm and 33% [N=921] of suicides by other means). Compared with the control group, suicide cases involving a firearm were significantly more likely to be associated with being older, being male, having lower education, or having lower incomes (

Table 1). Deaths by other means showed similar patterns, although there were no differences in education between cases of suicide and the control group.

Because age and sex varied significantly between cases and the control groups, we adjusted only for sex and age in our subsequent models for testing the association between specific mental disorders and general medical disorders and suicide by firearms versus other means. Adjustment primarily reduced the odds of firearm suicide among many conditions by correcting for cases being primarily male and older. The clinical differences between college education and income, although statistically significant, were not substantial enough to be considered clinically meaningful and for this reason were not included.

Table 2 shows the odds of having a mental disorder among suicide cases versus the control groups. Compared with the control groups, the odds of having a mental disorder were significantly greater among cases of suicide by firearm and cases of suicide by other means for all mental disorders, except autism. Notably, the odds of having a mental disorder were significantly larger for the other-means group compared with the firearm group across all mental disorders except autism, dementia, and tobacco use. For example, compared with the control group, the odds of having depression were significantly higher among cases involving other means compared with cases involving a firearm (OR=12.28 and 7.29, respectively). This implies that patients with mental disorders are more likely to use other means of suicide besides a firearm.

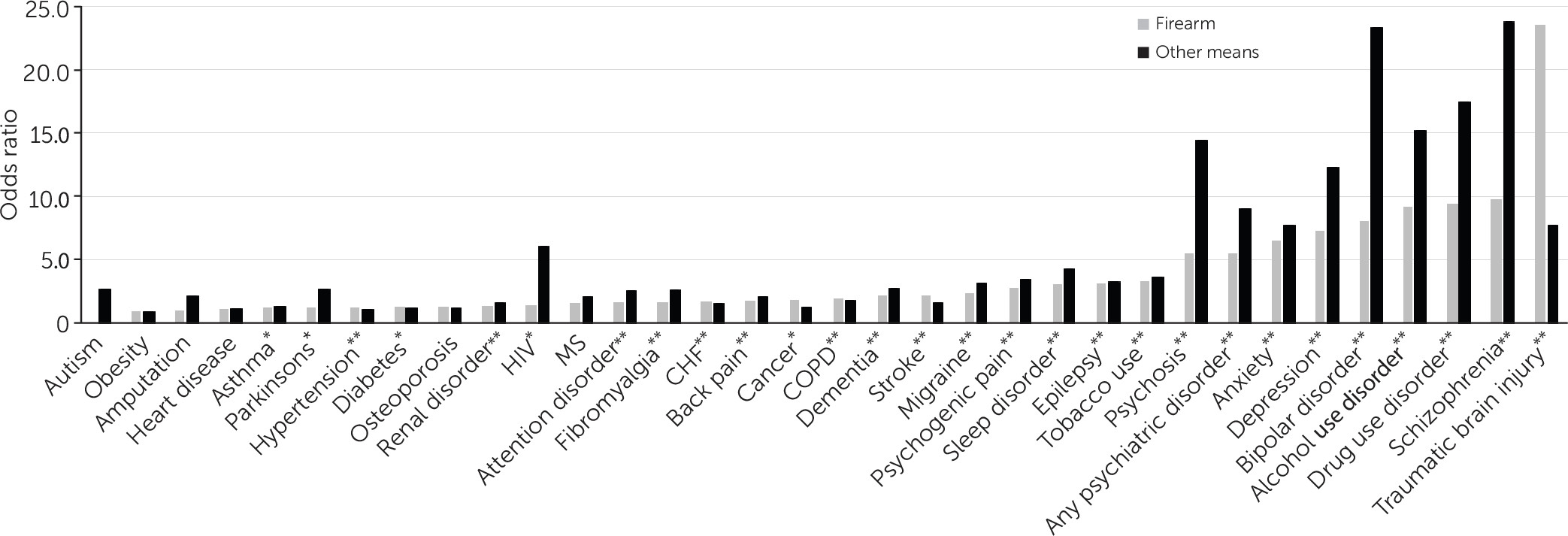

Table 2 also shows the odds of having a general medical disorder among suicide cases versus the control groups. The odds of having most general medical disorders were statistically significantly higher among suicide cases versus controls, but they were substantially lower than the odds of having a mental disorder, with some notable exceptions. The ORs for having a mental or general medical disorder by means of suicide, ranked from lowest to highest for firearms cases, are presented in

Figure 1. For suicide by firearm, the odds of having TBI (OR=23.53) and epilepsy (OR=3.17) were particularly high. For cases involving other means of suicide, there were particularly high odds for TBI (OR=7.74), epilepsy (OR=3.28), HIV/AIDS (OR=6.03), migraine (OR=3.17), and psychogenic pain (OR=3.47).

In our analysis of the burden of comorbid general medical disorders, we found a significant increase in the odds of firearm suicide among men with two or more general medical disorders versus no general medical disorders (OR=1.94) but not in the odds of suicide by other means (

Table 3). For women, we found the opposite pattern, with greater odds of suicide by other means among women with two or more general medical disorders versus no general medical disorders (OR=2.41) but no difference in the odds of death by firearm.

Discussion

We aimed to identify salient risk factors for suicide by firearm compared with other means that are easily identifiable by general medical and mental health providers. Our findings indicate that the odds of having a mental and substance use disorder were substantially less among cases of suicide with a firearm compared with cases of suicide with other means, and this was true for nearly all mental and substance use disorders. In our sample, the most common means of suicide other than a firearm, consistent with national statistics (

7), were medication overdose and suffocation or hanging. Assessing for stockpiles of medications and objects used for hanging (such as ropes and belts), which are often easily available in the home, is advisable for patients with mental health and substance use histories who are at risk of suicide (

6). Surprisingly, we observed that substance use disorders were associated with higher odds of suicide compared with many other mental disorders. This indicates the need for suicide risk mitigation for all means as a key component of substance use treatment. Training programs in lethal-means restriction counseling are available for mental health and medical providers, and several emphasize motivational methods to engage both patients and family members in safety planning (

6,

31).Family members are essential to help monitor access to all types of lethal means that may be readily available within the home, particularly means other than firearms that may be easily acquired by persons at risk. Ease of accessing means other than firearms may deter some providers from means assessment because eliminating access may seem impossible. Some means other than firearms, particularly overdose by nonopioid medications, are highly accessible and less lethal, which may deter clinicians from counseling to reduce access (

32). However, our results show that persons with mental disorders were more likely to use means other than firearms. A reasonable conclusion would be that our results indicate that counseling to reduce access to the most toxic or lethal substances or medications in overdose (for example, opioids) and materials used for suffocation (for example, ropes) would potentially reduce suicide among the large group of patients with mental disorders dying by means other than a firearm.

The results reported for general medical disorders do not control for co-occurring mental disorders, which affects the interpretation of our results for the association of general medical disorders with suicide. There is an established and well-recognized direct causal relationship between mental disorders and suicide, with 90% of families of suicide decedents reporting that the family member experienced psychiatric symptoms prior to death (

33). Our group conducted a prior study that compared the association of general medical disorders and suicide and controlled for the presence of mental disorders (

24). For this study, we chose not to control for mental disorders in our analysis of individual general medical disorders because half of patients who die by suicide do not have a mental disorder diagnosis coded in the medical record. Therefore, given that we assume that many patients who die by suicide have undiagnosed mental disorders, our results illuminate which general medical disorders should trigger additional risk screening. We do not assume that our results indicate a direct causal association between general medical disorders and suicide; instead, we suggest that the associations established here between suicide and general medical disorders indicate which of these disorders may co-occur with mental disorders and increase risk of suicide. Interestingly, the general medical disorders with the highest association with suicide in our results are those with high rates of comorbidity with mental disorders or those characterized by organic injury to the brain. Among cases of suicide by firearm, these included TBI, epilepsy, psychogenic pain, migraine, and stroke. Among cases of suicide by other means, we observed substantially increased odds of TBI, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, migraine, and psychogenic pain. Some prior literature from smaller samples, or large samples from other countries, suggests that each of these conditions may have an association with mental illness comorbidity, suicide ideation, or suicide attempt (

34–

39).

We chose to control for mental disorders in the analysis of comorbid general medical illnesses because we wanted to try to isolate the impact of comorbidity involving general medical disorders on suicide risk; however, we acknowledge that our estimates are potentially biased because of underdiagnosis of mental disorders. Nonetheless, our results should remind providers to pay attention to suicide risk among patients with comorbid general medical disorders. We observed that the risk of suicide among women with multiple comorbidities was notably higher for suicide by other means, but not for suicide by firearm. It is possible that much of this risk comes from prescription pain medication overdoses among women in middle age, especially white women (

40). Among the substances used for overdose, prescription pain medications (for example, opioids) are the most lethal (

41). Our results show especially high risk of fibromyalgia, back pain, psychogenic pain, and migraine among cases of suicide by other means; these are chronic pain conditions that are more common among women (

42), frequently involve pain medication prescription, and have high mental health comorbidity (

43–

45). This would indicate that women with comorbidities that involve prescription pain medications are at high risk of suicide. Medical providers may consider screening these women for suicide and if indicated, conduct subsequent assessment for stockpiles of medication as a lethal means for suicide.

For men, the impact of having comorbid general medical disorders increased risk of suicide by firearm, but not by other means. These findings are consistent with national surveillance data showing that men between the ages of 45 and 64 have the highest rate of firearm suicide death (

41). Additionally, in the United States, 45% of males own a firearm, compared with 11% of women (

46). In light of these data, general medical providers should consider suicide risk screening and subsequent assessment for access to firearms among men with comorbid general medical illnesses. A Florida law known as “Docs vs. Glocks,” which prohibits physicians from asking about or documenting gun ownership in medical records, was recently found to be unconstitutional (

47). A federal court determined that the right to free speech includes discussing firearms with patients and that doing so does not impinge upon the Second Amendment right to bear arms.

Conclusions

Our analysis suggests that general medical and mental health providers may wish to consider providing suicide risk assessment and means restriction counseling for several novel groups of patients, in addition to those with a recorded mental disorder. These groups include patients with a TBI, HIV/AIDS, epilepsy, a pain condition, stroke, and migraine. Men with general medical comorbidities should be targeted for suicide risk screening and counseled to reduce access to firearms when risk is detected. Persons with substance use disorders should be screened for suicide and assessed for access to both firearms and other means. Our results suggest a need for an analysis that directly investigates the link between prescription pain medication overdose and suicide mortality among women with pain conditions.