Psychiatric rehabilitation is designed to help individuals with serious mental illnesses develop the skills and access the resources needed to be successful and satisfied in the living, working, learning, and social environments of their choice (

1). An important aspect of psychiatric rehabilitation is supporting these individuals in exploring and achieving personal goals (

2–

4). The ability to make decisions about personal goals can be regarded as essential to a high quality of living for all individuals, including those with serious mental illness (

5,

6). In fact, personal goal attainment is one of the outcomes most highly valued by mental health care consumers (

6).

Being able to set and reach personally important goals has been found to increase autonomy, empowerment, well-being, self-confidence, and confidence in achieving future goals among individuals with serious mental illness (

6–

8). Goal setting and attainment link elements such as hope, responsibility, personal identity, and meaning in life and are therefore essential to recovery (

9,

10). It is also assumed that personal goal attainment will improve quality of life, which is often impaired among individuals with serious mental illness (

11,

12).

Working toward personal goals can be complicated for individuals with long-term mental illnesses, who may experience serious difficulties in retaining control over their lives. These difficulties may be caused by restrictions in the ability to take care of oneself; needs for support regarding housing, work, and social relations; and external factors, such as public stigma and the inability of others to see beyond symptoms. In addition, there is the “why try” effect, which encompasses self-stigmatization and anticipated discrimination and reduces self-esteem and self-efficacy, thus discouraging the pursuit of personally meaningful goals (

6,

13,

14).

As a consequence, psychiatric rehabilitation approaches have been developed that support these individuals in exploring their wishes and achieving personal goals, including individual placement and support (

15), which focuses on employment and education; illness management and recovery (

16), which focuses on illness self-management and personal goal attainment; and the Boston University approach to psychiatric rehabilitation (BPR) (

1). BPR supports individuals with exploring, choosing, and achieving goals related to housing, education, work, and social contacts. BPR was found to have positive effects on the attainment of self-chosen rehabilitation goals; social contacts and societal participation (

17,

18); personal and social functioning (

19); quality of life and symptoms (

18,

20); and empowerment, psychosocial functioning, and needs for care (

18).

Although BPR and other structured psychiatric rehabilitation approaches have been found to increase psychiatric rehabilitation success in terms of goal attainment, it is not clear what mechanisms are responsible for positive outcomes. The question also arises whether it is the specific character and content of each approach or some general factor that underlies rehabilitation success.

In the past decades, working alliance has emerged as a possible general factor explaining psychiatric rehabilitation success (

21,

22). It was found to have a positive influence on symptoms, level of functioning, social skills, quality of life, medication compliance, days of homelessness, and satisfaction with the care received (

23–

25). The working alliance can be described as a genuine cooperation between client and practitioner characterized by agreement on counseling goals, a shared commitment to the tasks of counseling, and the development of a personal bond between both actors (

26–

28). Previous research showed that working alliance robustly predicts rehabilitation outcome (

24,

29,

30). Gehrs and Goering (

31), for instance, found that the quality of the working alliance was positively related to rehabilitation goal attainment. However, the evidence for this specific relationship is sparse, and it remains unclear which aspects of the working alliance might cause this effect. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to investigate which aspects of the working alliance predict goal attainment in rehabilitation for individuals with serious mental illness, independent of the rehabilitation approach used.

The second aim was to investigate whether goal attainment would lead to improvements in the subjective quality of life of individuals with serious mental illness. This aim was to test the implicit assumption that working toward rehabilitation goals not only generates satisfaction with realizing the goals themselves but also improves subjective well-being in a more general sense.

These aims were addressed by conducting a secondary analysis of data from a 24-month randomized clinical trial (RCT) by Swildens and colleagues (

17). The RCT studied the effects of rehabilitation on goal attainment, comparing BPR with rehabilitation that was offered by practitioners with a more general background (generic rehabilitation [GR]).

Methods

Participants

Data were from a study that involved 156 individuals who were receiving inpatient and outpatient treatment at four mental health centers in both urban and rural regions in the Netherlands (

17; ISRCTN73683215). The study was conducted between June 2005 and June 2009. Inclusion criteria were as follows: a serious mental illness, operationalized as a

DSM-IV diagnosis; duration of service contact of at least two years; and enduring psychiatric disabilities. In addition, clients were eligible only if they expressed a desire for change in one of the rehabilitation areas (housing, education, work, and social contacts). Participants were recruited through their mental health care professionals. Individuals who had been in contact with a rehabilitation practitioner in the three months preceding baseline were excluded. Participants gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating mental health centers. At 24-month follow-up, 122 participants completed the interview. A detailed description of design and methods used has been published elsewhere (

17).

Measures

Working alliance.

The Working Alliance Inventory–practitioner perspective (WAI) was completed by the rehabilitation practitioner after the first three to four sessions and again after 24 months. It consists of 36 items that generate a total score and three subscale scores representing the different components of the working alliance: task (agreement about the tasks of the treatment or therapy and the responsibilities to perform these tasks), bond (between client and practitioner), and goal (agreement about the goals of treatment or therapy) (

28,

32,

33).

Goal attainment.

Goal attainment (yes or no) from the client’s perspective was measured at 24 months by means of a structured interview used in previous studies (

34,

35). Participants could choose a specific personal rehabilitation goal to work on in the following rehabilitation areas: living situation, work and study, and social contacts. The distinction between attainment and no attainment of this goal was conservative, meaning that partial goal attainment was seen as no goal attainment. If a goal was adjusted during the study period, the adjusted goal was evaluated instead of the original goal. If no information was available, goal attainment was conservatively set to no goal attainment.

Quality of life.

The self-report short version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) was scored at baseline and at 24 months. The WHOQOL-BREF encompasses 26 items and four domains: physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment. It shows good discriminant validity, content validity, and test-retest validity (

36). Possible scores on the WHOQOL-BREF range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction.

Psychiatric symptoms.

Mental health practitioners or psychiatrists completed the 24-item extended version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (

37,

38) at baseline and 24 months. The BPRS uses a 7-point Likert scale and is a reliable and valid instrument (

39,

40) with good internal consistency (α>.70).

Sociodemographic information.

Client-related predictors were gathered through a structured interview scheme at the start of the study, and checks were performed at 24 months.

Procedure

Structured interviews with participants were administered by trained interviewers and took approximately 75 minutes to complete. Mental health professionals also completed questionnaires. Interviewers were blinded to treatment allocation. Participants and mental health professionals could not be blinded.

Rehabilitation

All participants were offered at least one individual rehabilitation session every three weeks, without a predefined maximum number of sessions. Half the participants (N=80) received these sessions from 39 practitioners experienced in the BPR. These practitioners had backgrounds in social work, nursing, or vocational rehabilitation and had completed additional training in BPR. This approach is designed to support individuals with serious mental illness in all life domains (housing, education, work, and social contacts). In BPR, individuals are aided in exploring their options and in choosing and realizing clearly defined goals. Support is aimed at increasing personal skills as well as learning to make use of other potential sources of help (

41–

43). BPR consists of four phases: exploring, choosing, getting, and keeping rehabilitation goals (

43,

44). Each phase is accompanied by techniques that can be used by BPR practitioners to optimally support individuals in attaining their goals. Key to BPR is that the pace and direction of the process are directed by the individual. The practitioner facilitates the process and supports when necessary. Fidelity of BPR was measured with a fidelity scale (

45) showing that 86% of 39 BPR practitioners worked according to model standards.

The other half of the participants (N=76) received support from 63 mental health practitioners also trained in social work, vocational rehabilitation, and nursing care but without BPR training. These practitioners also supported clients with their personal rehabilitation goals but without using a structured approach or standardized methodology (

17). Both BPR and regular care practitioners received monthly supervision by supervisors using either BPR or generic mental health care methodology.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS, version 22.0, by using binary logistic regression for the categorical outcome measure of goal attainment (yes or no) and multiple linear regression for quality of life at 24 months. Student’s t tests were used to check differences in baseline characteristics between the BPR and GR groups and for quality of life at 24 months. Clusters of clients treated by the same practitioner were too small to conduct multilevel modeling. A possible clustering effect was dealt with by conducting a sensitivity analysis on a data set in which each practitioner had only one client (each first client) (

46).

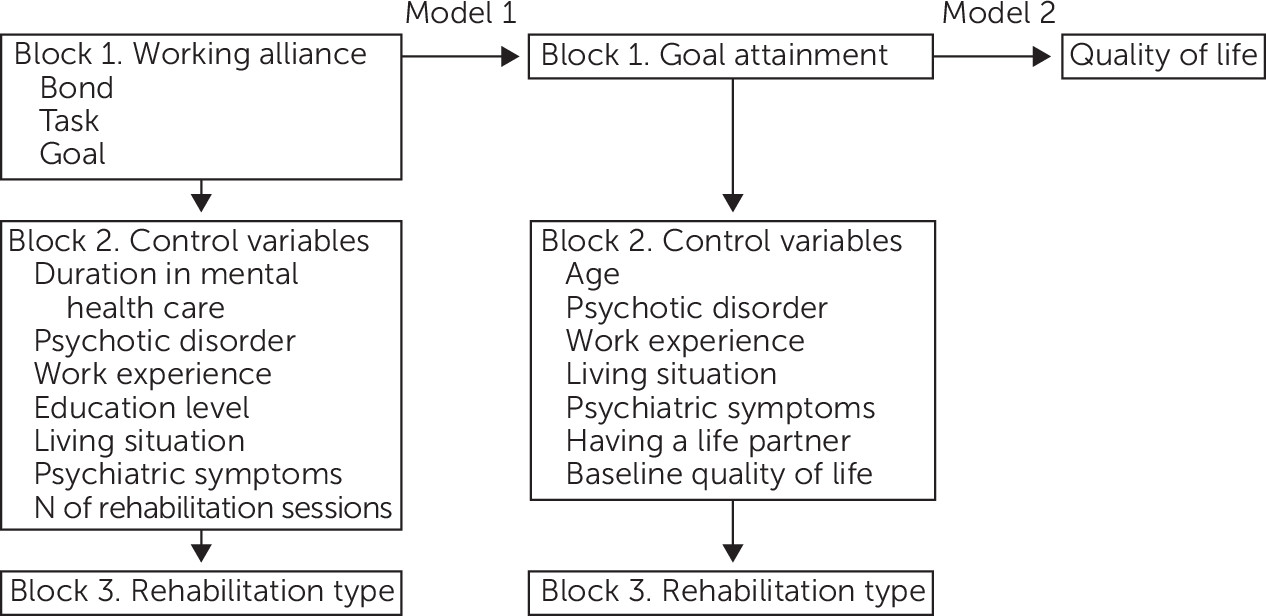

Two models were tested: model 1 with goal attainment as the dependent variable and working alliance as the predictor and model 2 with quality of life as the dependent variable and goal attainment as the predictor (

Figure 1). Because the choice of control variables was theory driven, the two models contained slightly different variables. Model 1 was controlled for number of rehabilitation sessions and for client-related factors known to predict rehabilitation outcome: psychotic disorder, psychiatric symptoms (

47–

49), duration in the mental health care, living situation (independent versus dependent) (

41,

50,

51), education level (

52), and recent work experience (

49,

50,

53). Model 2 was controlled for factors found to influence quality of life, such as age, psychiatric symptoms, psychotic disorder, living situation, having a life partner, and recent work experience (

54,

55). Working alliance was omitted in this model because of its expected association with goal attainment.

Finally, rehabilitation type was added as a control variable in both models because the RCT by Swildens and colleagues (

17) showed a significant effect for BPR on goal attainment and the study reported here focused on an effect of working alliance, independent of the effect of rehabilitation type. Variables with correlation coefficients higher than .75 or variance inflation factors >5 were not added to the model to avoid multicollinearity.

A stepwise procedure was applied in which variables were added in three blocks. For goal attainment as the outcome, the main predictors of interest—WAI task, bond, and goal subscales—were added first, and the following client- and process-related predictors were added in the second block: duration in mental health care, psychotic disorder, recent work experience, education level, living situation, psychiatric symptoms, and number of rehabilitation sessions. In the third block, intervention type was added.

For the model with quality of life at 24 months as the outcome, goal attainment was added first, followed by client-related predictors—age, psychotic disorder, recent work experience, living situation, psychiatric symptoms, and having a life partner. In the third block, intervention type was added. This model was controlled for baseline quality of life. Effect sizes were expressed as odds ratios for the logistic regression analysis, and Cohen’s f

2 was calculated for the multiple regression analysis (

56).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the participants and intervention are presented in

Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two study groups (

17).

Goal Attainment

During the study, 54% (N=84) of participants switched goals. After 24 months, 39% (N=61) of participants were reported to have fully reached their goals.

Table 2 shows that higher scores on the WAI goal subscale and having received BPR predicted goal attainment at 24 months. None of the other predictors were found to have a significant effect.

The sensitivity analysis with only one case per practitioner showed similar results: WAI goal score (B=.16, SE=.08, p=.04) and intervention type (B=1.27, SE=.57, p=.03) significantly predicted goal attainment (R2=.246) (data not in table).

Quality of Life

At 24 months, there was a significant improvement in quality of life compared with baseline for all participants who were interviewed. The mean±SD WHOQOL-BREF scores were 83.95±13.64 at baseline and 88.22±15.09 at 24 months (t=−3.52, df=115, p=.001).

Goal attainment significantly added to a positive change in quality of life at 24 months (

Table 3), as did age. The sensitivity analysis yielded the same result for goal attainment (B=7.63, SE=3.15, p=.02; R

2=.410, R

2adj=.312; Cohen’s f

2=.695) (data not in table).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore predictors of successful rehabilitation goal attainment by focusing on working alliance as a possible generic determinant independent of rehabilitation methodology. Furthermore, the assumption underlying the emphasis on goal attainment in state-of-the-art rehabilitation was put to the test: does quality of life improve when rehabilitation goals are attained?

Apart from a significant effect for intervention type in accordance with the findings of Swildens and colleagues (

17), the goal component of the working alliance proved to be the main predictor of successful goal attainment, whereas the personal bond between practitioner and client and a shared commitment to the tasks of rehabilitation did not predict goal attainment. This finding suggests that agreeing with the client on goals is more important than simply establishing a personal bond or agreeing on how to achieve these goals.

Furthermore, this study showed a significant effect of goal attainment on improvement in 24-month quality of life, thus supporting the assumption that agreeing on goals helps individuals with serious mental illness to enhance their quality of life. This positive effect provides a wider context for the importance of working on personal goals. Working on goals with individuals with serious mental illness is not only important in itself but also offers a useful tool to help clients gain control and live meaningful lives according to their own wishes.

The predictive effect of working alliance on therapeutic outcome has been reported in meta-analyses on psychotherapeutic interventions and seems to be very consistent (

30,

57,

58). Although it could be argued that a good outcome promotes positive evaluation of the relationship with the therapist instead of the other way around, in this study the relationship was evaluated at the start of the intervention, thus clearly preceding outcome. Gehrs and Goering (

31) also found that working alliance was positively related to goal attainment, but, as in most studies, they treated the client-practitioner relationship as a single concept without discerning aspects responsible for its effect on outcome. The findings of the study reported here make clear that agreement on goals is particularly important for goal attainment. This is in line with the concept of shared decision making, which emphasizes the importance of listening to an individual’s goals, thus encouraging empowerment (

59–

61). Our findings stress that this process also plays a central role in successful goal attainment.

A limitation of this study was that working alliance was measured only from the practitioner’s point of view. Working alliance from clients’ point of view was found to be an even stronger predictor of outcome (

62,

63). However, Martin and colleagues (

30) found that practitioner ratings were only slightly less reliable than client ratings, and Ruchlewska and colleagues (

64) found that practitioner-rated working alliance was a better predictor of completion of a crisis plan than was the client-rated alliance. It has been suggested that the different views may reflect different but related concepts of the working relationship, because client and practitioner ratings are often associated with different variables (

65,

66).

Furthermore, the WAI and other frequently used measures of the working alliance were developed from the context of psychotherapy and may lack aspects of the working alliance that are specific to psychiatric rehabilitation settings. Examples of such aspects are the sometimes involuntary nature of the relationship, because clients in long-term care are often not able to freely choose their mental health practitioners, as well as the dual role of practitioners, who need to facilitate their clients’ autonomy but are also responsible for their health and safety (

67). Therefore, it would be useful to develop measures that specifically capture the working alliance in rehabilitation settings. A final limitation was the fact that participants were included only if they had a desire for change. Therefore, results may not apply to less motivated individuals.

Agreeing on goals is specific but not exclusive to a BPR-based approach. Our findings suggest that agreement on goals is an important facilitator of goal attainment for rehabilitation practitioners, independent of their background and rehabilitative approach. Nevertheless, the effect of rehabilitation type indicates that methodology-specific aspects also influence the effectiveness of a structured rehabilitation approach such as BPR. This is also supported by the fact that the model explained only 15% of the variance in goal attainment. The rest of the variance could be explained by methodology-specific or other general factors not investigated in this study. Future research directed at uncovering these factors could help further elucidate the mechanisms responsible for goal attainment among individuals with serious mental illness.

Conclusions

It is often stressed that a positive working alliance forms the basis for a fruitful therapeutic process. This study showed that this is true but only to the extent that practitioner and client agree on rehabilitation goals. Just forming a bond or agreeing on the tasks required to achieve the goals did not predict goal attainment. These findings imply that rehabilitation practitioners could improve outcome by discussing clients’ wishes and goals and by setting a goal that is mutually agreed on. This focus will improve rehabilitation as well as the subjective quality of life of those involved. These results are not limited to a specific rehabilitation approach but rather reflect general predictive mechanisms of rehabilitation goal attainment and quality of life, which makes them applicable to rehabilitation practitioners from various backgrounds and perhaps even to other mental health care providers.