The history of modern psychiatry in China is relatively short. The number of psychiatrists in China is very limited and unevenly distributed, with most working in major cities and in the more socioeconomically developed regions (

1). In 2010, there were only 1.46 psychiatrists and 15 beds per 100,000 people in China (

1)—rates much lower than in other countries and regions (

2). Unlike psychiatrists in most countries, practicing psychiatrists in China are often employed by hospitals and very few are in private practice (

1). Although the government has collected some basic data on practicing psychiatrists in the past decade and some have been made public (

3), the information is rather limited, sporadic, or filtered because the data are based primarily on hospital administrators’ reports.

Although studies from other countries suggest some general issues, many socioeconomic factors are unique to Chinese psychiatrists and deserve closer scrutiny. Therefore, we conducted a survey with the goal of using the results to guide policy making and resource allocation.

Results

Distribution of Participating Hospitals Across China

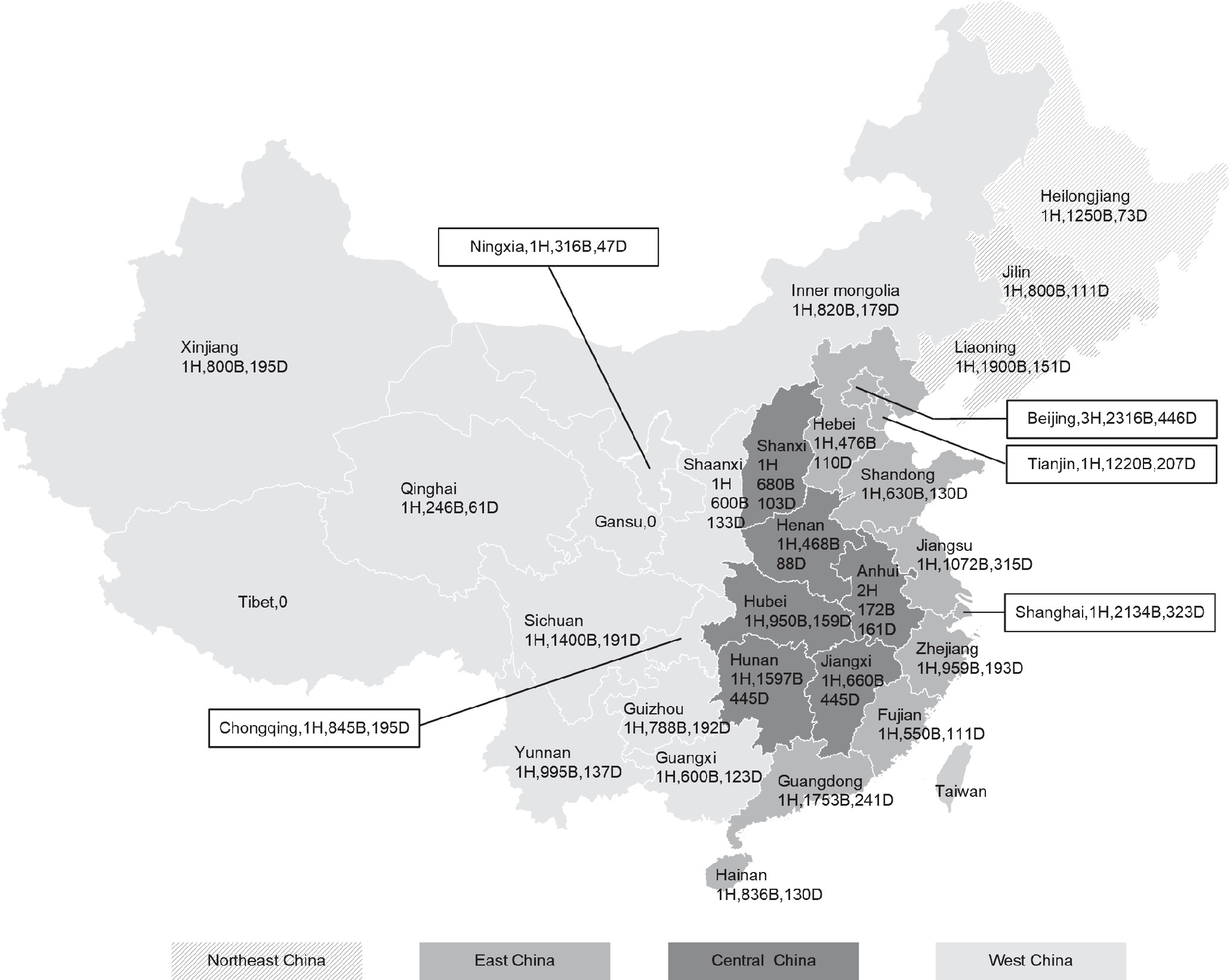

The geographical distribution of the 32 psychiatric hospitals is shown in

Figure 1. Twelve hospitals were selected from East China, which is more population dense and socioeconomically developed, and ten hospitals were from less developed West China. The hospital sizes varied, with bed numbers ranging from 169 to 2,134. The doctor/bed ratios also varied, ranging from .1 to .3.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

In total, there were 3,363 psychiatrists in the selected hospitals, and they were all invited to participate. A total of 2,715 responded to the questionnaire (response rate, 81%), and 2,602 (77%) completed the questionnaire. The results presented here are for completers only.

Table 1 provides data on demographic characteristics of the sample. Most psychiatrists were female (58%), and the vast majority (83%) were between the ages of 30 and 49. Most (89%) were married, and 85% had children. Regarding education level, 25% had a master’s degree and 5% had a doctorate degree in addition to their medical degrees; 95% had medical degrees or add-on degrees (65% had medical degrees only), and 4.7% had associate degrees or other technical education. More women had add-on degrees (33%) than men (25%) (p<.001).

Working Hours and Monthly Income

The mean±SD number of working hours per week was 47.1±10.6, and no significant difference was found between male and female doctors. A significant regional difference was found in working hours per week: West China, 49.2±12.3; Central China, 47.0±10.6; East China, 46.6±9.4; and Northeast China, 43.6±8.2 hours (p<.05). In this study, 61% of participants reported working more than 40 hours per week (the standard). Again, regional differences existed, with a significantly higher percentage of participants reporting more than 40 hours per week in West China (66%), compared with East China (61%), Central China (62%), and Northeast China (40%) (p<.05).

The reported actual and expected incomes varied widely (

Table 2). To make the incomes comparable across different regions, we standardized the incomes by local city average incomes, and used Beijing as a benchmark. Psychiatrists’ incomes were 1.2 times (1.2±.4) the average income for the local city. Overall, the average income of psychiatrists in China was low, with a median of 11,191 RMB (roughly $20,660 a year). As reported elsewhere (

18), male psychiatrists reported significantly higher incomes compared with their female counterparts (p<.01). Those who worked in socioeconomically developed regions (East China) reported significantly higher incomes compared with those working in other regions (p<.05).

Disputes and Complaints and Perception of Social Environment

In this survey, medical disputes and complaints included all incidents involving complaints or grievances reported by patients or their families regarding medical services, treatment outcome, or medical expenses, which may or may not actually represent medical malpractice (

19–

21). In China, most medical disputes and complaints are reviewed and managed by hospital administrators or mediated by a third-party mediation service (

20).

In the sample, 40% of psychiatrists had experienced medical disputes and complaints in the previous year, and they occurred more commonly among male psychiatrists than among female psychiatrists (44% versus 36%, p<.001). Regional differences were found, with the highest percentage of psychiatrists reporting medical disputes and complaints in Central China (44%), and the lowest in Northeast China (30%).

In the sample, 56% of participants had malpractice coverage, and the rate varied widely by region. West China had the lowest percentage of psychiatrists covered (47%), and Northeast China had the highest percentage (68%). The differences were significant (p<.05).

Participants did not believe that the public attitude toward health care workers or the social environment in China were supportive of mental health professionals. Most participants (79%) were not satisfied with the social environment; participants in West China were most likely to feel dissatisfied (84%), and those in Northeast China were least likely to feel dissatisfied (69%). In addition, 69% of participants did not believe that they received their due respect from the public; those in West China were most likely to not feel respected (78%), followed by those in Central China (67%), East China (66%), and Northeast China (56%) (p<.05).

In contrast to the high rate of dissatisfaction with the external social environment, our data showed that most psychiatrists appreciated their collegial and collaborative relationships with nurses. Overall, 76% were satisfied with doctor-nurse cooperation (East China, 80%; Central China, 78%; West China, 67%; and Northeast China; p<.05). In addition, 76% were satisfied with the trust between doctors and nurses (East China, 81%; Central China, 79%; West China, 65%; and Northeast China, 84%; p<.05).

The most commonly reported reasons for job dissatisfaction were low pay (42%), contentious doctor-patient relationships (21%), and a high workload (13%). Less common reasons included overregulation (8%), low social status (8%), and poor administrative support (3%), with 5% reporting other reasons.

Quality of Life and Health Status Self-Assessment

Overall, 18% of psychiatrists were satisfied with their quality of life (East China, 22%; Central China, 18%; West China, 12%; and Northeast China, 20%; p<.05). In addition, 25% of psychiatrists were satisfied with their health status (East China, 26%; Central China, 26%; West China, 23%; and Northeast China, 29%; p>.05).

MSQ and Associated Factors

The overall MSQ score in this sample was 71.6±14.3, suggesting only moderate job satisfaction. Significant gender differences were found (males, 70.9±14.8; and females, 72.1±14.0; p<.05) as well as regional differences (East China, 74.1±14.3; Central China, 71.3±13.8; West China, 66.3±13.5; and Northeast China, 76.6±13.4; p<.05).

A multilevel analysis was used to examine associations between individual factors and total MSQ scores. In the null model, the intraclass correlation was 18%, and thus multilevel analysis was necessary. As shown in

Table 3, younger age, shorter work hours per week, higher monthly pay, a smaller gap between expected and actual pay, being in an administrative position, having medical liability insurance, not having experienced medical disputes and complaints, being satisfied with doctor-nurse cooperation, being satisfied with hospitals’ medical dispute resolutions, and being satisfied with the social environment for health care workers were all significantly associated with higher satisfaction.

In this study, 20% of psychiatrists reported the intention to quit their jobs. When asked whether they would choose their profession if they could choose again, 42% answered that they would not choose the same profession, and 24% answered that they would. More than half (58%) reported that they did not want their children to become psychiatrists, and nearly half (48%) did not want their children to be medical doctors in other specialties.

We randomly selected 75% of the sample to set up the multilevel logistic model (

Table 4). The analysis indicated that turnover intention was associated with younger age (odds ratio [OR]=.7), being male (OR=1.4), being in an administrative position (OR=1.7), having experienced medical disputes and complaints in the previous year (OR=1.3), having low job satisfaction (OR=.3), and having a low monthly income (OR=.8). The forecast accuracy of the model for the remaining 25% of the sample was 83%.

Discussion

This was the very first nationwide survey focusing on the sociodemographic features, job satisfaction, and related factors pertaining to psychiatrists in China. A few strengths of this survey need to be mentioned. The survey covered nearly all provinces and autonomous regions (29 of 31) in mainland China, and the participation and completion rates were both very high. The high rates were partly attributable to the strong organizing and coordinating efforts of the parent project. The survey was conducted online to ensure anonymity and reliability. All data were collected within a short time period, which allowed the data to be more comparable cross-sectionally. Of note, this was also the first survey conducted after the comprehensive national Mental Health Law came into effect in 2013.

On the other hand, a few limitations of the study also need to be acknowledged. First, there are limitations inherent to a self-report study design, especially reliability. In addition, because of the many local dialects in China, some questions on the survey might have been interpreted in different ways by various participants. For example, the Chinese term for medical disputes (Yiliao Jiufen) is very broad and inclusive. Participants may have had varying interpretations of the phrase.

Another limitation is the sampling method. We selected only the provincial psychiatric hospitals in the capital cities of each province. Although the sample was large in this survey, the representativeness of the entire population of Chinese psychiatrists was limited. Our sample accounted only for approximately one in ten (10.7%) of the approximately 24,000 Chinese registered psychiatrists in 2017 (

1,

3). Our samples were based on the tertiary hospitals, and these hospitals often have more resources than the district- or county-level hospitals. All hospitals were within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health (Health Section). Hospitals within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Social Welfare were not selected. The survey was conducted only in specialized psychiatric hospitals; psychiatrists working in general hospitals were not included. As a result, our data may not be generalizable to psychiatrists working in hospitals outside the health sections or in district- or county-level hospitals, hospitals located in rural areas, or general hospitals.

This study had a few important findings. First, the average MSQ score was only 71.6, which is very similar to the findings in a sample of nonpsychiatrist physicians in China (N=1,620) (

22). This score is significantly lower than scores seen in almost all studies of high-income countries, such as Finland and Switzerland (

23–

25). Second, alarmingly high percentages of psychiatrists were not happy with their social environment. In this survey, 69% of psychiatrists thought they did not receive their due respect from the public, and 79% were not satisfied with the social environment for medical workers. Third, nearly two-fifths of psychiatrists experienced medical disputes and complaints in the previous year, and one-fifth reported the intention to quit their jobs.

The low incomes of psychiatrists in China can be better appreciated given the following facts. First, the incomes of clinical doctors in China are considerably lower than those of other professionals of similar background or education (

26). In 2015, the incomes of psychiatrists were in the middle range of all clinical specialties, with an average of 79,000 RMB per year ($12,150) (

27). Second, considering the cost of living and other factors, the average income of our sample was only 1.2 times the local average income. Third, the average income of our sample ($20,660 per year) was less than one-tenth of the annual compensation of psychiatrists in the United States ($273,000) (

28).

Most survey participants were female (58%), and females reported significantly lower pay compared with their male colleagues. Because their salaries were graded on the basis of their education, degrees, and professional titles, and because more female psychiatrists had add-on degrees than male psychiatrists, it is less likely that female psychiatrists received lower basic pay. Instead, the salary difference could be the result of other factors, such as a hidden gender gap in bonus distributions, fewer women in administrative positions, and fewer women promoted professionally. All of this could be a manifestation of the traditional gender inequality in China (

29,

30).

In this sample, 95% had medical degrees or add-on degrees: 25% had an add-on master’s degree, and 5% had an add-on doctorate degree. Less than 5% had an associate degree or other education(lower than a college degree). This is encouraging compared with the findings of a recent national survey, which found that 43% of prescribing psychiatric practitioners in China did not have a medical degree in 2013 (

1). Because of historical reasons, some prescribing psychiatric practitioners in China have only an associate degree; although they are referred to as “psychiatrists,” they often hold the lowest professional title and usually work under a supervising psychiatrist, similar to that of a nurse practitioner or a physician assistant in the United States.

In this survey, 40% of psychiatrists experienced medical disputes and complaints in the previous year. This rate seems to be in line with reports from the United Kingdom (

31), United States (

32), Australia (

33), Japan (

34), and Taiwan (

35), where medical disputes and complaints have increased in the past decades. However, unlike in developed countries where malpractice insurance is universal and mandatory, only 56% of our sample had malpractice coverage. This is an area that clearly needs improvement.

Overall, the satisfaction level of Chinese psychiatrists was lower than in most studies from other countries, especially high-income countries. For example, 88% of Australian psychiatrists were satisfied with their work and proud of their profession, and a large majority of them (69%) would choose to become psychiatrists if they could choose again (

25). In contrast, only 24% of our sample would choose the same profession again.

The most common reasons for dissatisfaction were low pay, contentious doctor-patient relationships, and a high workload. According to the Australian study, reasons for dissatisfaction reported by psychiatrists in public hospitals were lack of beds (47%), administrative demands (40%), lack of support from administrators (39%), and lack of resources (39%) (

25). Many of these reasons were related to limited resources for patient care; however, our sample was more likely to cite reasons that were personal in nature. Similar findings were also seen among nonpsychiatrist physicians in China, among whom the most common reasons for dissatisfaction were low pay, high workload, and overregulation (

36).