Suicide is a major public health issue in the United States. More than 40,000 Americans die by suicide each year. In the past two decades, suicide rates increased by more than 20%. This increase included males and females in all age groups (

1–

3). Mental health conditions are widely considered to be risk factors for suicide. Most studies that have investigated this association have focused on suicidal ideation or suicide attempts as outcomes (

4,

5). Few studies have examined risk of suicide mortality as the main outcome (

6–

12).

The research gap is particularly evident within the U.S. general population. In a U.S. veteran population, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder were found to be associated with a two- to threefold increased risk of suicide death (

8). In Sweden and Denmark, the suicide mortality rate was higher among patients with bipolar disorder (

13,

14), compared with the general population. Schizophrenia was found to be associated with an elevated risk of suicide mortality in a national clinical survey in England (

15). In a U.S. study, Brown and colleagues (

16) found that mood disorder, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder were associated with a three- to tenfold increased risk of suicide mortality. However, most of these studies were conducted in other countries or within the U.S. veteran population, and there is limited data from the general U.S. population pertaining to individual psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide death.

This study aimed to fill this gap by using health care data to study suicide mortality in the general U.S. population. The data used in this study allowed a comprehensive look at the relationship between diagnoses of mental health conditions and suicide mortality. All diagnoses from all health care settings in a large and diverse population were recorded. We also assessed whether risk of suicide death differs by sex, given the wide variations between men and women in rates of suicide death, mental health conditions, and health care utilization.

Methods

Data Source

The Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), a consortium of 13 health care systems across the United States, collectively provides health care services to more than 15 million demographically and geographically diverse individuals each year (

www.mhresearchnetwork.org). All MHRN sites have organized their electronic medical record and insurance claims data into locally stored federated data systems called the Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW). Affiliated health plans provide a diverse range of health insurance for individuals, including commercial, private, Medicaid, and Medicare plans. The same data definitions and variables are included across sites to facilitate multisite research. These data include comprehensive capture of encounters, procedures, diagnoses, providers, cancer-tumor, pharmacy, vital signs, laboratory values, demographic characteristics, and insurance enrollment across large, multispecialty health care delivery systems.

In this study, data were collected from the following eight health care systems: Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (Massachusetts), HealthPartners (Minnesota), Henry Ford Health System (Michigan), and Kaiser Permanente systems in Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington. Suicide mortality data were identified from official state mortality records by using

ICD-10-CM codes from X60 to X84 and Y87.0. Information on health care utilization in the year before the index date was obtained from all health care settings, including inpatient, outpatient specialty, emergency, and primary care. A detailed data description has been published previously (

17). Institutional review boards at each health system approved the use of deidentified data for this research.

Study Sample and Study Design

This study used a case-control design. A total of 2,674 individuals who died by suicide between 2000 and 2013 and were health plan members at one of the eight participating health systems were considered as being in the case group. The date of death was considered to be the index date for individuals who died by suicide, and the same date was selected as the index date for matched patients in the control group. Patients in the case and control groups were continuously enrolled in the health care system’s health plan for at least 10 months during the year before the index date. As a control, each patient who died by suicide was matched with 100 patients from the general population of patients. Control group patients were randomly selected among health plan members enrolled in the same health care system and during the same period as patients in the case group. Thus all patients in the case and control groups were matched by site and enrollment period. A total of 267,400 patients who did not die by suicide were included in the study as the control group. Patients who were in the control group survived for at least 10 months in the year before index date and did not die by suicide.

Measurements

Diagnostic codes were extracted from the VDW for the year prior to the index date for all patients in the study. Five types of mental health conditions were defined by

ICD-9-CM codes, including anxiety disorders (codes 300.0, 300.2, 300.3, 309.20, 309.21, 309.24, and 309.81), attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (code 314), bipolar disorder (codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–7, 296.5–296.7, 296.80, 296.81, and 296.89), depressive disorders (codes 296.2, 296.3, 296.82, 298.0, 300.4, 301.12, 309.0, 309.1, 309.28, and 311), and schizophrenia spectrum disorder (code 295). These diagnoses were chosen because they represent the most prevalent psychiatric diagnoses among the general U.S. population (

8,

13–

16); other psychiatric diagnoses are seldom made. The findings for substance use disorders were too comprehensive to include in this study. Therefore, we decided to present those findings in a separate report and to focus this report on the five conditions listed above.

Insurance type was captured from the VDW with the classifications of commercial, Medicaid, Medicare, private pay, and other. Neighborhood income and education were calculated by using geocoded address and U.S. Census Bureau block data. Individuals were considered to be of low income if they resided in a census block where >20% of residents had an income below the U.S. poverty level. Individuals were considered to have a high education level if they resided in a census block where ≥25% of residents were college graduates.

Statistical Analysis

Conditional logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between mental health conditions and suicide mortality. Each diagnosis was coded as a dichotomous variable (yes or no) to indicate the diagnosed condition in the year prior to the index date. The model was adjusted for age, insurance type, and sociodemographic characteristics. A fully adjusted model was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and all diagnosed mental health conditions. For patients with multiple diagnoses, each diagnosed mental health condition was flagged in the model simultaneously to determine the contribution of each predicted factor while the analysis controlled for the others. All models were conditional on site and index year.

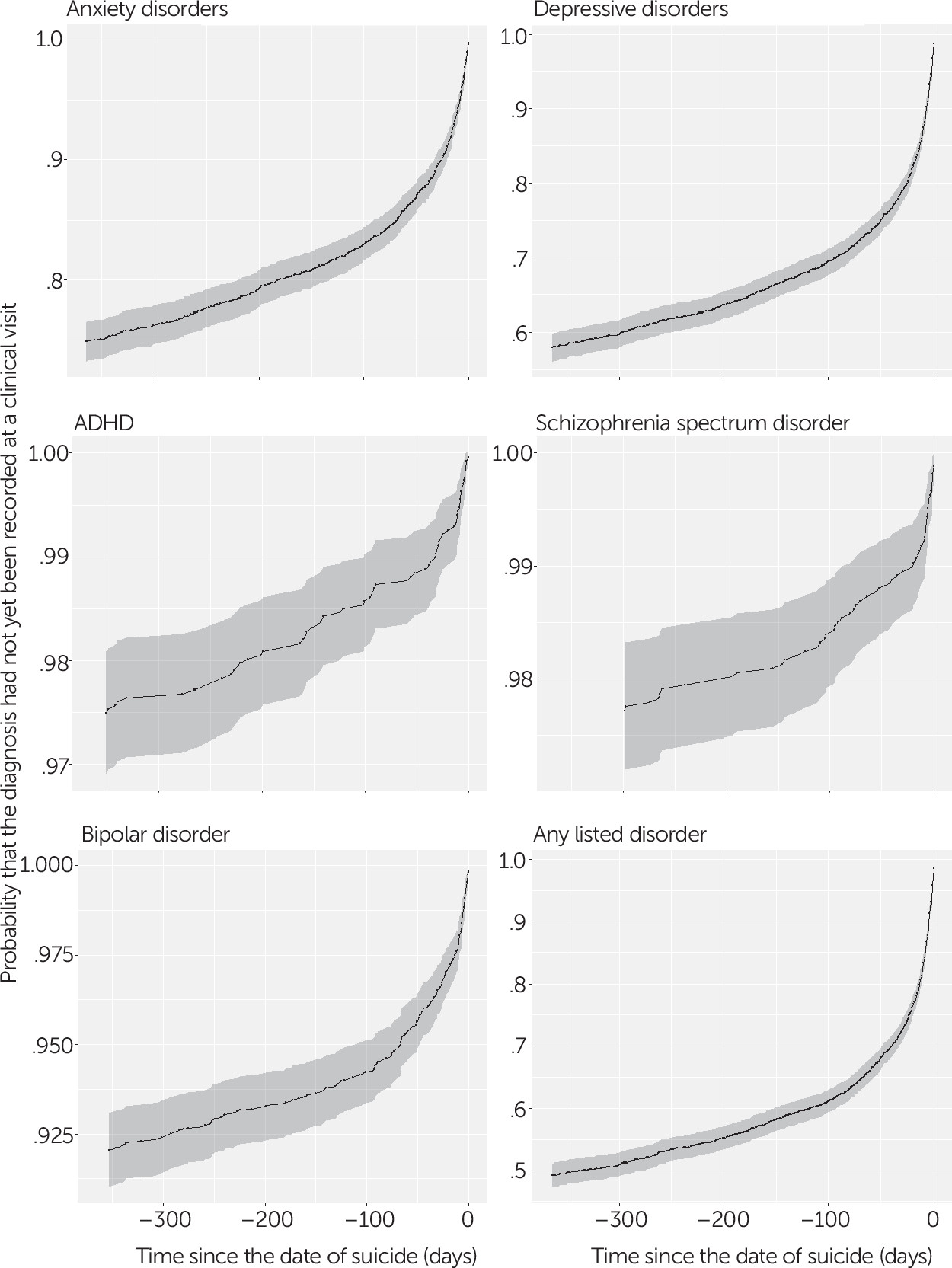

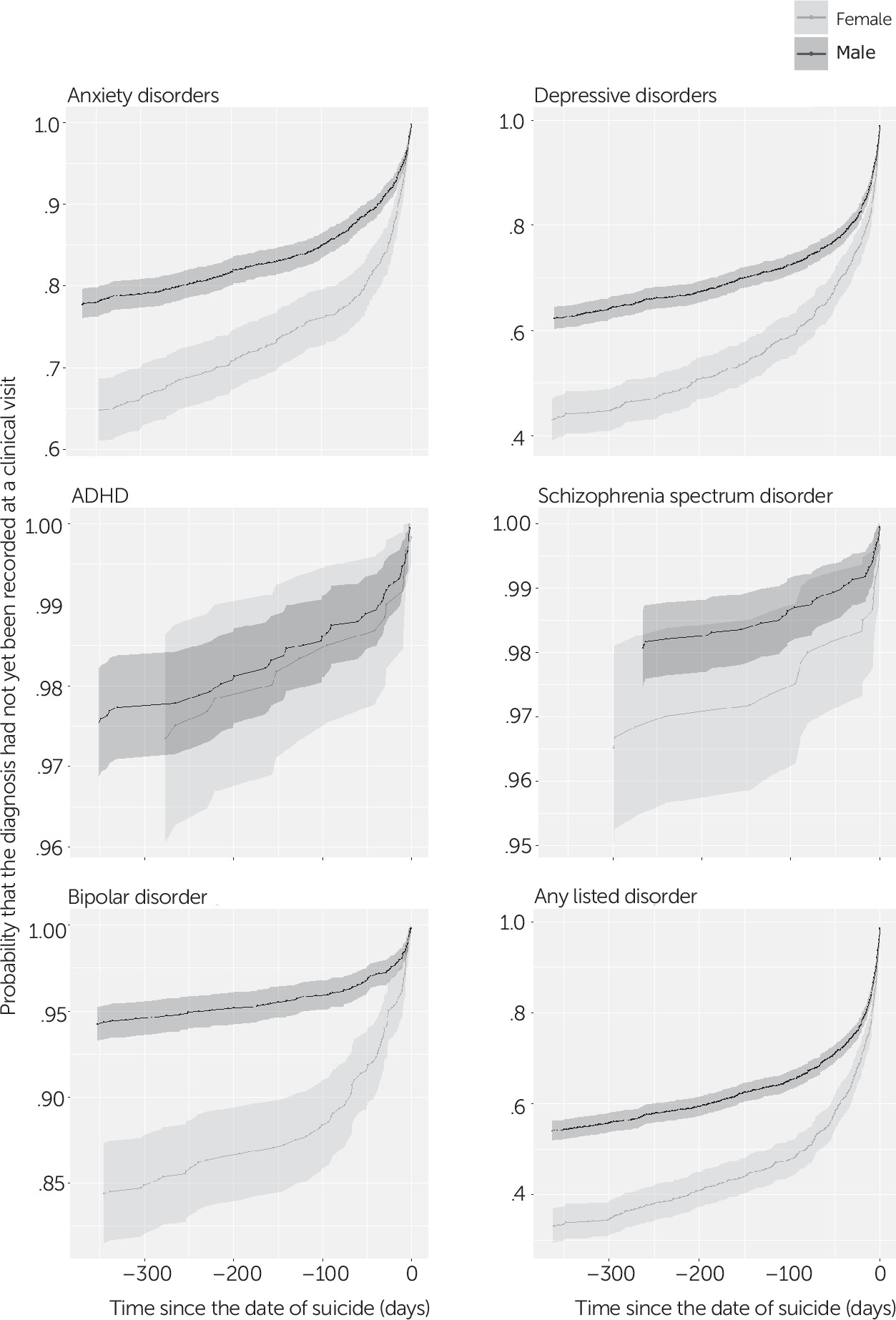

Among individuals who died by suicide, time was documented from the index date backward to the date of each diagnosed mental health condition in the reverse-survival analyses. For individuals with multiple diagnosed mental health conditions that contributed to the time-to-event information for multiple Kaplan-Meier survival curves, the time between the diagnoses was competitive. The event used in this analysis was the last clinical visit for which the relevant diagnosis was coded. Time was measured from the index date backward to the event for each recorded mental health condition. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to capture the probability of the last clinical encounter for which the relevant diagnosis was recorded before suicide death and are displayed backward with time.

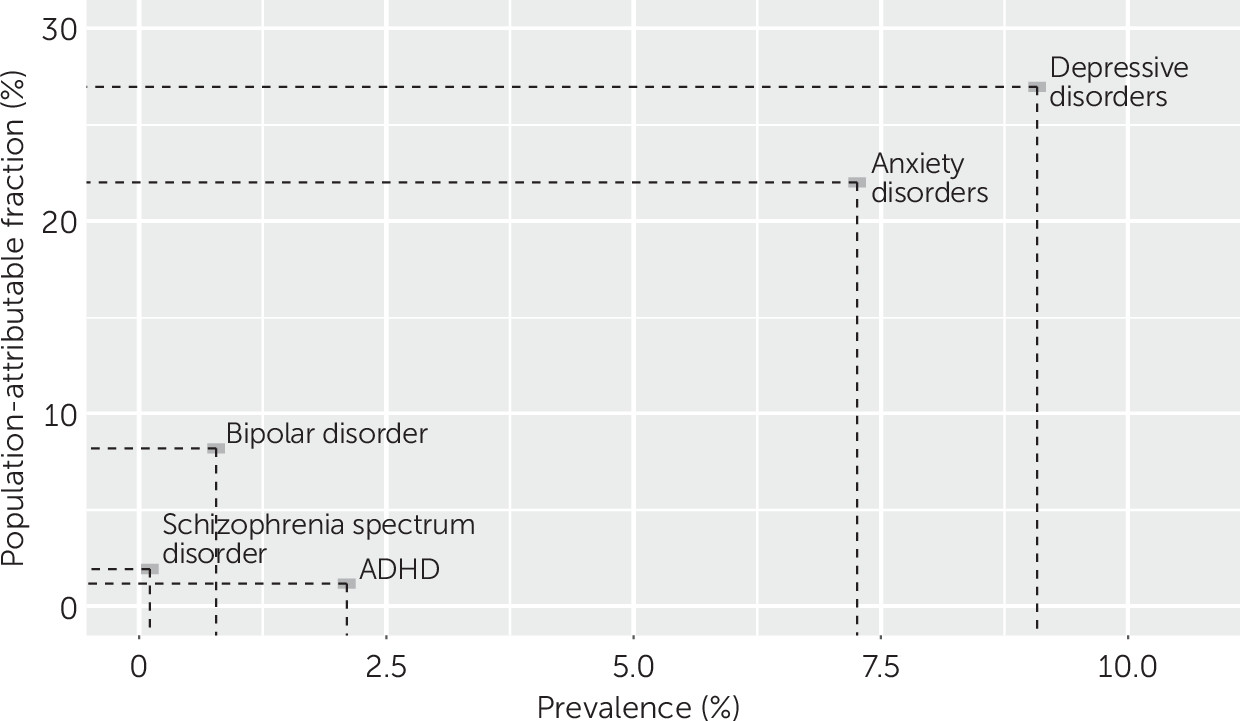

The effect of psychiatric diagnoses on suicide mortality in the population was examined by calculating the population-attributable fraction (PAF). The prevalence of each mental health condition was obtained from MHRN data.

All analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.4, and R-Studio, version 1.136.

Results

Individuals who died by suicide were more likely than the control group to be male (77.5%) and to have had at least one diagnosed mental health condition in the year before suicide (

Table 1). Overall, 51.3% of those who died by suicide had at least one of the listed diagnosed mental health conditions in the year before the index date, compared with 12.7% of patients in the control group. Those who died by suicide had, on average, more health care visits for diagnosed mental health conditions prior to the index date, compared with patients in the control group (5.2 versus 0.6 visits, respectively).

Table 1 also shows the number of days between the last visit with a diagnosed mental health condition and suicide death among those who died by suicide. The shortest interval was found among those with a diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum disorder (45.4 days), and the longest was among those with ADHD (87.0 days).

Overall, having a diagnosis of a mental health condition in the preceding year was associated with a higher risk of death by suicide (

Table 2). After the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, individuals with diagnosed mental health conditions in the year prior to the index date were 6.8 times more likely to die by suicide (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=6.84). Diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder were associated with the highest relative odds of suicide mortality. Compared with patients with no diagnosed mental health condition, patients with diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum disorder in the year prior to the index date were 15 times more likely to die by suicide (AOR=15.00) and those with bipolar disorder were 13 times more likely (AOR=13.17). Elevated risks were also observed for depressive disorders (AOR=7.20), anxiety disorders (AOR=5.84), and ADHD (AOR=2.37). After adjustment for all listed diagnoses (fully adjusted model), suicide risk remained highest among individuals with diagnoses of bipolar disorder (AOR=5.14), depressive disorders (AOR=4.98), and schizophrenia spectrum disorder (AOR=4.88). The estimated effect of ADHD on suicide mortality was no longer significant after adjustment for the other diagnoses.

After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and stratification by sex, women with diagnosed mental health conditions in the preceding year had higher relative odds of death by suicide, compared with men (AOR=10.60 versus AOR=8.27, respectively). Women with diagnosed mental health conditions of bipolar disorder, depressive disorders, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder had higher relative odds of death by suicide, compared with men. Among those with diagnosed bipolar disorder, the relative likelihood of dying by suicide was significantly higher among women than among men (AOR=22.87 versus AOR=12.60). Overall, the effect of psychiatric diagnoses on suicide mortality was higher among women than among men.

We performed additional analyses to investigate how substance use disorders might affect the results presented in

Table 2. After adjustment for substance use disorders in the model adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and the fully adjusted model separately, the AORs were attenuated. For example, individuals with any of the listed diagnosed mental health conditions in the year prior to the index date were five times more likely to die by suicide after adjustment for substance use disorders and sociodemographic characteristics. [Tables with details from these analyses are provided in an

online supplement to this article.]

Kaplan-Meier survival curves with inverse time were used to estimate the probability of diagnosed mental health conditions before suicide death (

Figure 1). Nearly 40% of individuals who died by suicide had at least one clinical visit with a recorded mental health condition within 3 months before suicide death. This gradually increased to approximately 50% up to within a year before suicide death. In the year before suicide death, more than 40% of individuals had a recorded depressive disorder, followed by 15.0% with anxiety disorders, 7.5% with bipolar disorder, 2.5% with ADHD, and 2.1% with schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Individuals who died by suicide often had psychiatric diagnoses recorded within the 3 months before the index date.

Nearly 50% of women who died by suicide had at least one clinical visit with a recorded mental health condition within the 3 months before suicide death, compared with 35% of males (

Figure 2). In addition, in the year before suicide, more than 65% of women who died by suicide had at least one recorded mental health condition, compared with 45% of men.

To reflect the importance of both relative odds and prevalence, we evaluated the PAF of suicide mortality associated with diagnosed mental health conditions in the year before suicide death. An estimated 27% of suicide deaths were attributable to depressive disorders, 22% to anxiety disorders, 8% to bipolar disorder, 2% to schizophrenia spectrum disorder, and 1% to ADHD (

Figure 3).

Discussion

This study found that nearly 50% of individuals who died by suicide had at least one diagnosed mental health condition in the year before suicide death. Nearly all mental health conditions were associated with an increased risk of suicide mortality, and this risk was highest among those with bipolar disorder, depressive disorders, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder. In addition, among individuals who died by suicide, a greater proportion of women had recorded mental health diagnoses in the year before suicide, compared with men (65% versus 45%). Moreover, with respect to the PAF within health care systems (i.e., MHRN), an estimated 27% of suicide deaths were attributable to depressive disorders.

The findings of this study are similar to those of previous studies in other populations. Bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder are three of the most common diagnosed mental health conditions associated with suicide death. Among veterans, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder were found to be associated with increased risk of suicide death (

8). Suicide risk among individuals with any of the listed diagnosed mental health conditions was slightly lower in the veteran population than in our study sample. One explanation could be that the proportion of men is higher in veteran populations and that men are less likely to have diagnosed mental health conditions. Two studies found a similar result; more than 40% of individuals who died from suicide had a diagnosis of depression or bipolar disorder within 12 months before death, and more than 20% had a diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum disorder (

7,

18). A meta-analysis also showed that the risk of suicide among patients with bipolar disorder was 20 to 30 times greater than for the general population (

19).

Previous studies, in the general population and among veterans, have found that, compared with persons without anxiety, those with anxiety were more likely to have suicidal ideation, attempted suicides, or completed suicides (

4,

8,

20,

21). Our findings are consistent with these. However, because disorders are “bundled” in the data set, we were not able to tease apart the various anxiety disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder.

Studies have examined male-female differences in suicide risk among individuals with diagnoses of mental health conditions (

8,

13,

22–

26). Previous studies found that suicide risk was higher among those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorder, especially for women (

22,

26). These findings are in line with those of our study. In a Swedish population, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for suicide was especially high among individuals with bipolar disorder (

13). SMRs for suicide were eight times higher among men with bipolar disorder and ten times higher among women with bipolar disorder, compared with deaths by natural causes. Sex differences could be explained by the evidence that depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorder are more common among women than among men. In addition, women are more likely to seek mental health treatment (

27,

28), thus making them more likely to have a recorded mental health condition. This finding is important for men, given that they have a much greater overall risk of suicide but are much less likely to have a diagnosed mental health condition. This suggests that outreach and universal suicide prevention approaches may be needed, especially for men in a health system who are not diagnosed as having any of the listed mental health conditions (

28).

The association between ADHD and suicide was higher among women than among men after the analysis adjusted for the effect of age and other socioeconomic factors. Although ADHD is more common among men (

29), women with ADHD were found to have a much higher risk of self-harm and suicide attempts, compared with men (

30). However, the association between diagnosed ADHD and suicide mortality was no longer significant in our analysis after adjustment for other mental health conditions, suggesting that persons with ADHD and another of the listed conditions are at greater risk of suicide mortality from the other condition than from ADHD.

Health care utilization within 1 month or 1 year before suicide has been examined in other studies (

31–

33). In this study, we examined the estimated probability of clinical visits with a recorded mental health condition month by month, from 1 month to 12 months prior to suicide. These findings contribute a more detailed time frame for suicide deaths. Approximately 40% of those who died by suicide had at least one recorded mental health condition within 3 months prior to suicide, a finding similar to those of previous studies (

32,

34,

35). This suggests that there are opportunities to intervene with patients within the health care environment prior to suicide, which supports the need for effective identification, assessment, and treatment. The national Zero Suicide initiative provides recommendations for structured processes to accomplish these care pathways (

36).

These analyses provided estimates of population-level relative risk and of the number of individuals at risk in the population. Both are important issues to consider when assessing the relationship between mental health conditions and risk of suicide. For example, patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorder are at the highest relative risk of suicide death, but they also represent smaller numbers of individuals. In terms of numbers, the largest number of individuals who died by suicide were those with depressive and anxiety disorders, and these individuals may be the focus of larger suicide prevention approaches across the health system. Conditions with greater relative risk but lower numbers may be assessed and treated with higher-intensity interventions. Conditions that occur among more individuals but that have lower relative-risk estimates may be the focus of larger systemwide efforts, including lower-intensity screening and intervention approaches.

The data presented in this report represent real-world diagnoses in the clinic. However, these findings must be viewed in the context of several limitations. First, uninsured individuals were not included in the study population. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to this group, such as for calculating attributable suicide deaths. Second, the severity of mental illness was not available in the clinical data collected for this study. Data on severity could provide more context for these findings. Third, patients who did not survive for at least 10 months in the year before the index date were not included in the control group. This exclusion criterion might have influenced differences between the case and control groups. For example, we may have excluded from the control group persons with mental disorders who died by drug overdose in the year before the index date. Finally, all recorded diagnoses of mental health conditions were coded by health care providers. Therefore, some conditions may have been undetected or not coded in clinical records because some individuals may not have presented with symptoms during a clinic visit or may have presented with symptoms that did not meet criteria for a full diagnosis.