The OpenNotes initiative is a growing international effort that encourages health care systems and clinics to provide patients online access to clinical progress notes to help them become more involved in their care (

https://www.opennotes.org). Clinical notes are progress notes written in the medical record by clinicians and other staff that document their interactions with patients. In the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), patients who are users of VHA’s online patient portal, My Health

eVet, may access their clinical notes. Organizations are increasingly providing patients access to clinical notes online. However, unlike many other organizations, the VHA does not give clinicians the option of deciding which notes are available to patients. VHA rolled out OpenNotes nationally in January 2013, and nearly half of the almost 2 million active My Health

eVet users have used the portal to read or download their clinical notes via the Blue Button since they became available (

1).

Prior research suggests that the transparency of clinical notes can benefit patients by increasing health-related knowledge, strengthening the patient-clinician relationship, and empowering patients—that is, making them feel in greater control of their care and recovery (

2,

3). Although most patients and clinicians view OpenNotes positively, some clinicians and others have raised concerns about potential unintended negative consequences of patients’ online access to clinical notes regarding mental health treatment, which often contain sensitive information. Feared negative consequences include damages to the therapeutic relationship, unnecessary confusion or worry among patients, complications to overall patient-provider communication, and impacts to workflow by requiring additional time to more carefully write notes or to address patients’ concerns (

4,

5). In a prior survey of 263 VHA mental health clinicians, 85% of respondents agreed with the statement, “making medical record notes available online is a good idea,” but nearly half reported that they would feel somewhat or very pleased if use of OpenNotes for mental health treatment was discontinued (

6). Additional qualitative work suggested that OpenNotes has the potential to improve the therapeutic process when patients perceive the notes to be transparent and respectful. If, however, patients believe the notes fall short in these areas, the notes may have a harmful effect on the therapeutic process (

7). In interviews, mental health clinicians indicated wanting more guidance on how to write notes and provide care in the context of OpenNotes (

4).

We developed a Web-based course for VHA mental health clinicians designed to reduce the potential for unintended consequences and enhance the likelihood of positive outcomes of using OpenNotes in this setting. Specifically, the course aimed to improve clinicians’ understanding of OpenNotes, provide guidance on note-writing strategies, and enhance patient-clinician communication about notes. Here we report on the extent to which the course had an impact on self-reported clinician attitudes and patient-clinician communication behaviors related to use of OpenNotes in VHA mental health care.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VHA facility where the study was conducted. Prior to study activities, we received a waiver of documentation of written informed consent for all participating clinicians. Data were collected between August 2016 and July 2017.

Setting

VHA launched its online patient portal, My Health

eVet, in 2003. VHA patients can use My Health

eVet to conduct a variety of tasks, such as refilling prescriptions, sending secure messages to providers, and reviewing upcoming appointments. All clinical notes written since January 1, 2013, can be accessed to view or download by using the Blue Button link 3 days after notes are completed. This study was conducted at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Portland Health Care System, in Portland, Oregon—a large VA facility in the Pacific Northwest. This facility serves approximately 95,000 veterans at 11 urban and rural sites throughout the region. Demographic characteristics of veterans at the facility are similar to those of the veteran population nationally: average age, 63; and proportion treated who are male, 92%. The proportion of veterans who are white is higher than the national average: 87% versus 83%; this difference reflects the general population of the region (

8). Approximately 250 mental health clinicians (physicians, psychologists, social workers, and nurse practitioners) provide mental health services to approximately 16,000 veterans each year. In late 2012 and 2013, clinicians and other staff at the facility were made aware of OpenNotes through all-employee e-mails. These e-mails described OpenNotes and the Blue Button feature, provided tips on clinical documentation, and reported summary statistics on previous research on OpenNotes.

Web-Based Course Development

In consultation with stakeholder (veteran and clinician) consultants, an instructional designer, and a contracted team experienced in learning management software and course development, the study team created an interactive Web-based course on OpenNotes for mental health clinicians called “VA OpenNotes for Mental Health Clinicians” (

Box 1; a detailed course outline is available from authors upon request). The course was designed to take approximately 30 minutes to complete, be viewable on stationary and mobile devices, and to familiarize clinicians with OpenNotes and provide recommendations for practicing in the context of OpenNotes. Course content includes basic information about using OpenNotes and information about writing notes to prevent unintended negative consequences, having conversations with patients about notes, and using OpenNotes to enhance care. Course content was derived in part from interviews with 28 mental health clinicians and 28 patients receiving VA mental health care about their experiences, concerns, potential benefits, and advice regarding OpenNotes (

9). To address some of the concerns expressed by clinicians during these interviews, we also drew on previous research and writings relevant to patient-clinician communication (

10,

11).

Procedures

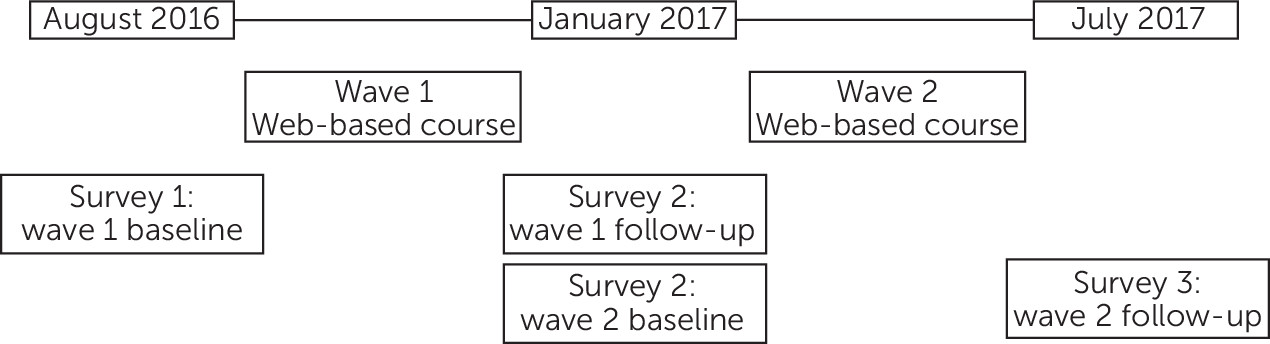

All 251 mental health clinicians at the medical center were eligible to participate; continuing medical education was available for course participation. The Web-based course was delivered in two waves, and study participation involved completion of a survey at three time points that spanned the two waves (

Figure 1). Delivering the course in two waves allowed us to look for secular trends over the course of the study. We sent a preparatory e-mail to all mental health clinicians introducing the study, followed by an e-mail two days later with an individualized link to the first survey. Clinicians who participated in the first survey (N=141, 56%) were randomly assigned to receive the Web-based course in either wave 1 or wave 2.

Longitudinal Survey

Many survey items were adapted with permission from Delbanco and colleagues’ (

2) prior study of OpenNotes conducted at three non-VA health care settings. The study reported here utilized data from 10 items that specifically addressed clinicians’ attitudes and patient-clinician communication behaviors related to OpenNotes. We also administered the Clinician Support–Patient Activation Measure (CS-PAM) (

12), a well-validated and often-used measure of participants’ level of support for patients’ management of their health and health care, and the Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship–Clinician scale (STAR-C) (

13), a validated measure that assesses clinicians’ perceptions of their therapeutic alliance with their patients. The CS-PAM and the STAR-C were administered at survey 1 for use as covariates in the final models.

Analysis

To optimize applicability to real-world implementation of training on OpenNotes, we used an “intent-to train” approach, meaning that we decided, a priori, to use data from all 141 clinicians who completed survey 1 in our analyses, regardless of their level of participation in the course. We first compared survey 1 responses of the clinicians in each of the training waves by using t tests with unequal variances. To explore for secular trends, we ran paired t tests to compare survey 2 to survey 3 responses for clinicians participating in training wave 1 and survey 1 to survey 2 responses for clinicians participating in training wave 2.

To compare pretraining to posttraining data, survey 1 served as the baseline survey for participants assigned to wave 1, and survey 2 (administered 4 months later) served as their follow-up survey. Similarly, survey 2 served as the baseline survey for participants assigned to wave 2, and survey 3 (administered 4 months later) served as their follow-up survey. In other words, pre-post comparisons used participant data from only one baseline and one follow-up survey. We calculated mean pre- and posttraining scores, and to assess changes in outcome measures we ran paired t tests comparing the mean differences in item responses on communication behavior and attitudes between baseline and follow-up time points. Next, to account for our longitudinal research design, we conducted analyses using mixed-effects linear regression models with repeated measures for each participant. All mixed models were adjusted for gender, discipline (prescribing clinician [psychiatrist or nurse practitioner] versus nonprescribing clinician [psychologist or social worker]), and STAR-C score. The number of weekly hours of patient care, CS-PAM scores, years since clinical training, and training wave were nonsignificant covariates and were thus excluded from further analyses. We imputed the missing follow-up survey data for one of the wave 1 clinicians by using that clinician’s survey 3 data, and we imputed missing baseline data for nine of the wave 2 clinicians by using their survey 1 data. All statistical analyses were conducted with R, version 3.4.4 (

14), and mixed-effects models were run by using the lme function from the nlme package, version 3.1–131.1 (

15).

Results

Of the 141 clinician participants who completed baseline surveys, 63% were female, 50% had been in practice for more than 10 years, and 54% provided more than 20 hours of patient care each week (

Table 1). Forty-six percent were social workers, 34% were psychologists, 16% were psychiatrists, and 4% were nurse practitioners. There were no significant differences in gender or discipline between clinicians who participated in this study (N=141) and those who did not (N=107). Across both waves, 113 (80%) of those who completed the baseline survey also completed a follow-up survey; this group constituted the main analytic sample for the analyses described below. We detected no significant differences between the two training waves in their survey 1 responses and no secular trends. These analyses suggested that there were no initial differences between waves, and that pre-post changes were not attributable to increased familiarity with OpenNotes that might naturally occur without training.

Table 2 shows participants’ mean changes in outcome scores between baseline and follow-up and results of final adjusted mixed models. In final models, which used data from the 113 clinicians with complete data, we found that after course participation, there was a significant increase in clinicians’ perceptions of their ability to communicate with and educate their patients (–.22, p<.01; item was reverse-scored). Reductions in worry about negative consequences were also significant (–.17, p=.05). No significant pre-post score changes for the three remaining attitude items were noted.

Three of five communication behavior items showed improvements. After taking the course, clinicians reported more frequently educating their patients about OpenNotes access (.27, p<.001), advising patients to access and read their notes (.23, p<.01), and asking patients about questions or concerns they have with their notes (.16, p=.04).

We conducted a post hoc multivariable sensitivity analysis that included only the clinicians who accessed the course, according to Web log data (N=97 of 113, 86%). Overall results did not change; however, the change in score from baseline to follow-up on the item about asking patients if they have questions or concerns about their notes was no longer significant. In an additional post hoc analysis, we found no significant differences in demographic characteristics or item responses between the clinicians who completed only the baseline survey (N=141) and those who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys (N=113).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first published study to evaluate a training program for mental health clinicians on OpenNotes. Clinicians in our sample reported improvement in perceptions of their ability to communicate with and educate patients: they more frequently educated their patients about OpenNotes, advised patients to access and read their notes, and asked patients about questions or concerns that they may have about their notes. Although a limitation of this study was that it did not employ a randomized two-arm design, analyses across the two training waves suggested that the observed pre-post changes were not significantly attributable to an increased familiarity with OpenNotes that might occur without training over time.

In a prior cross-sectional survey study, many clinicians felt that patients would worry more after reading notes about their mental health (

6). A follow-up qualitative study showed that although some clinicians viewed OpenNotes as an opportunity to better partner with patients, others felt that it had the potential to undo the therapeutic relationship (

4). The latter study also found that mental health clinicians often desired more education and support to help them work effectively within the context of OpenNotes. An additional qualitative study of veterans demonstrated that although patients often wanted to discuss their clinical progress notes with clinicians, patients were often reluctant to bring up the topic (

7). These prior findings suggest that additional education and support specifically focused on helping patients and clinicians communicate about notes are needed. Communicating about notes was thus incorporated as a key component of the learning objectives. In a separate article, we reported the specific advice patients and clinicians had for clinicians practicing in the context of OpenNotes; this advice informed the learning objectives for the Web-based course (

9).

In the study reported here, we found that the Web-based course resulted in positive impacts on self-reported communication behaviors and on reducing worries about negative consequences. However, no significant impact was noted on clinicians’ mean ratings of concerns about maintaining the treatment relationship in the context of OpenNotes. It may be that clinicians need to test new communication approaches in actual practice over time before determining to what extent treatment relationships may be positively or negatively affected.

VHA’s practice is unusual in that patients are granted access to all of their mental health notes by default. However, multiple institutions have begun to promote shared online health record access for patients receiving mental health care (personal communication, Wachenheim D and O’Neill S, 2018). This movement is supported by our and others’ prior research with patients receiving mental health care, which has shown that reading progress notes often helps patients feel more in control of their health care, better able to understand their mental health and general medical conditions, and better able to remember their plan of care and to have more trust in clinicians. In contrast, relatively few patients have reported frequently feeling distress or worry after reading their notes (

16,

17).

Several important limitations should be considered with regard to the study. As noted above, we did not randomly assign clinicians to a training group versus a control group with no training; however, our use of two waves (to which clinicians were randomly assigned) and collection of longitudinal data across those two waves allowed us to evaluate for secular changes. Forty-five percent of eligible clinicians contributed complete data for the multivariable analysis; this rate of participation may affect generalizability of the results to other clinician populations. Of note, we detected no differences in gender or discipline between clinicians who participated in this study and those who did not. All measures were self-report and thus may not reflect actual clinician practice. We did not measure long-term outcomes. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons. However, comparisons were planned. That is, we designed this analysis and selected the outcomes regarding attitudes and behaviors for comparison prior to conducting the analyses; in this case, adjustments for multiple comparisons may not be as useful (

18). Finally, this study examined a sample of clinicians from one VHA facility, and generalizability may be limited in terms of other VHA facilities or other clinician populations.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that wider dissemination of this or similar courses to mental health clinicians may help them communicate with their patients about OpenNotes and may reduce apprehensions about OpenNotes. Our prior research has shown that both clinicians and veterans need more support in order to use OpenNotes productively (

4,

6,

7,

9). Furthermore, if we want patients who receive mental health care to be able to take advantage of the potential benefits that the OpenNotes initiative may offer, training approaches such as the one tested here should be implemented.