The dichotomy between hospital and community psychiatry is a cornerstone of mental health policy in countries around the world. Consider the title of a press release from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development: “The Netherlands Has an Innovative Mental Health System, but High Bed Numbers Remain a Concern” (

1). Despite the mental health system’s otherwise admirable performance record, the persistence of inpatient care appears troubling. Assuming a trade-off, many international organizations prefer community care to hospital care, as do many researchers, advocates, and national policy makers (

2–

4). A modern, comprehensive psychiatric system presumably should condense its inpatient bed supply and instead develop the supply of outpatient care programs. This belief, however, relies upon uncorroborated evidence, and cross-national data challenge its validity.

Hospital and Community Psychiatry

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines inpatient psychiatric care as specialized, hospital-based overnight medical care for people with mental disorders (

5). Community care, by contrast, includes non–hospital-based care, such as community mental health centers, outpatient clinics, day care centers, sheltered workshops, and clubhouses, for people with mental disorders (

5). This latter form of care emerged in the late 20th century, when financial considerations, human rights movements, and the development of antipsychotic medications facilitated the deinstitutionalization of people with psychiatric conditions out of “insane asylums” in affluent countries. Since then, observers in both developed and developing countries have rejected institutional care as an inappropriate, or otherwise antiquated, approach in most instances.

The preference for community care guides much of the research in mental health, although with deficiencies. Longitudinal research has found that deinstitutionalization was associated with lower mortality rates among people with mental disorders, but the concomitant improvement in mortality rate among the general population remains a confounding factor (

6). Similarly, a meta-analysis published in 2014 found that shorter psychiatric hospital stays were associated with higher social functioning, but the analysis included only six studies conducted between 1969 and 1980, when treatment in inpatient wards differed markedly from contemporary practices (

7). Additionally, cross-sectional research has not shown conclusively that people with mental disorders accessing community services fare better than people accessing institutional care (

8,

9). This is because researchers tend to compare study groups to control groups lacking access to either type of care and because the patient populations of institutional and community-oriented services are frequently incomparable.

Despite the lack of conclusive evidence against the effectiveness of contemporary hospital psychiatry, memories of past abuses in mental asylums linger. Many advocates and policy makers presume that rejecting institutional care will foreclose the possibility of additional abuse, even if some forms of outpatient care raise similar possibilities (

10). Many also believe that expanding community care will reduce overall mental health expenditures (by diverting patients away from costly psychiatric hospitals) and destigmatize mental health care (by promoting the social inclusion of those with a mental illness). Although some analysts have suggested that “bringing back the asylum” could correct some of the negative aspects of deinstitutionalization (such as the increased risk of homelessness, neglect, or imprisonment), skeptics of this argument worry that its return could hamper the development of community-oriented services (

11,

12). Only by reducing hospital care and expanding community care, it is presumed, can societies optimize the treatment, empowerment, and ultimately, quality of life of people with mental disorders.

Cross-National Evidence

If the desired expansion of community psychiatry rests on the reduction of hospital care, then societies with ample outpatient care should have very little inpatient care. Data from the WHO Mental Health Atlas (

5), a comprehensive survey of mental health services around the world, can help to examine this argument. Cross-national comparisons are riddled with conceptual and measurement challenges. In order to redress them, the WHO sends a standardized questionnaire to in-country experts, usually government officials, who submit national statistics on the mental health system according to the definitions identified above. The survey results are, to be sure, an imperfect reflection of country trends. Variations in national health system design mean that national data collection patterns may not match the survey protocol. But to the best of my knowledge, no national expert has publicly challenged the ensuing general characterization of his or her country’s mental health system. In short, the survey yields imprecise, but reasonable, results.

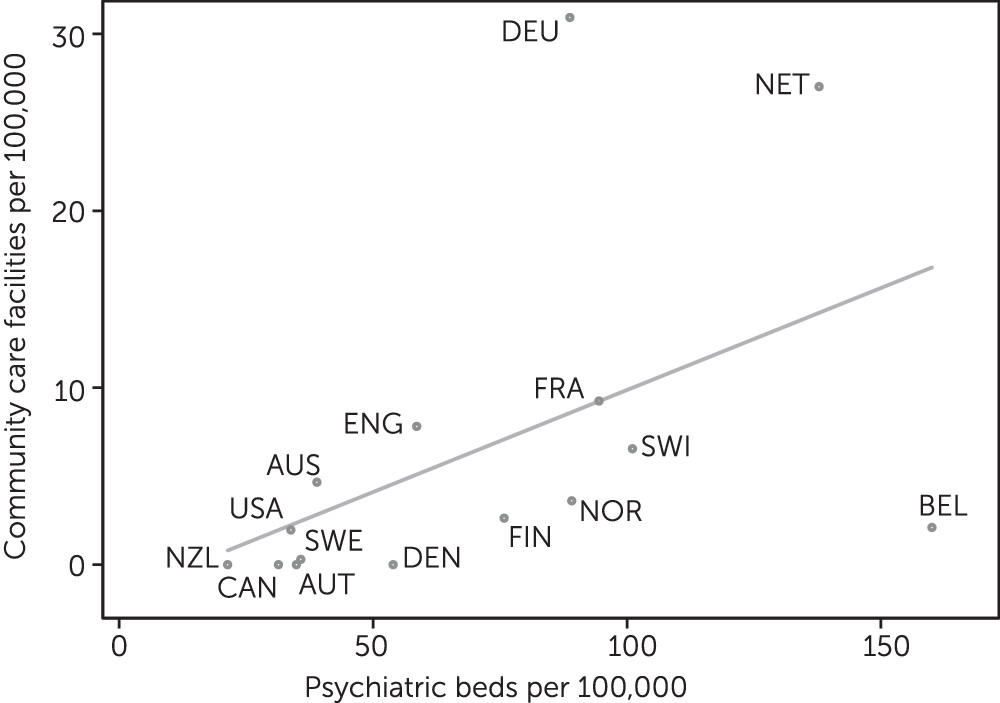

Figure 1 uses the survey data to compare the supply of mental health outpatient and day facilities to the supply of psychiatric beds in 15 democracies. The wealth accumulated by these countries in the late 20th century generated the kinds of social programs that could facilitate hospitalized patients’ transitions into the community, an experience that in turn reframed international expectations for the care of individuals with a mental illness. The figure presents all available data on mental health service provision in these countries, except for nonhospital residential facilities (present in only a few countries). These facilities blend elements of community and hospital services by combining nonmedical social care with overnight care and therefore cannot clearly be categorized as either community or inpatient care.

The figure shows a direct positive association between the supply of inpatient and outpatient care. Generally, countries with high levels of inpatient care also provide high levels of outpatient care (e.g., the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, Germany). Meanwhile, the countries that provide the least amount of inpatient care (e.g., the United States, New Zealand, Denmark, and Sweden) tend to provide the least amount of outpatient care as well. The inclusion of nonhospital residential facilities does not reverse this association. When these facilities are included in either category, the association between community and hospital psychiatry remains positive (not shown). Notably, the countries with more psychiatric beds tend to house them in specialized psychiatric hospitals, not in the psychiatric wards of general hospitals (

5). Taken together, the data suggest that expanding the supply of some types of specialized psychiatric services expands the supply of others, both inside and outside the hospital.

Conclusions

More research is needed to determine whether and why psychiatric inpatient care and community services are positively correlated. The first step is to develop better definitions and measures of these services. Historically, the responsibilities of the “mental institution” were both medical and custodial. Deinstitutionalization, however, decoupled these tasks, rendering many definitions and measures of psychiatric services obsolete. Today, the boundaries of community and institutional psychiatry are often permeable. Some psychiatric hospitals provide extensive medical treatment but aim for short-term stays. Meanwhile, some community facilities operate primarily as long-term social services, not as health care providers. Facilities such as sheltered apartments, day hospitals, and rehabilitation centers are difficult to categorize according to a simple dichotomy.

With updated language and indicators, researchers will be better able to explain the links between different types of services. One hypothesis is that the hospital serves a coordinating role. In the same way that general hospitals develop outpatient units, urgent care centers, and satellite clinics, so too do hospitals diversify their psychiatric services. Moreover, the prominence of specialized psychiatric hospitals in countries with a high overall supply of mental health care suggests that these hospitals are particularly likely to develop community services. Further research could compare services attached to hospitals with those not attached to hospitals, investigate whether the former exceeds the latter, and if so, determine why. Additional research could also examine how the coordination of different types of psychiatric services shapes patterns of care and coordination in the overall health system.

A second related hypothesis concerns the structure of payment. As the principal financial centers of mental health care, psychiatric institutions are equipped to develop outpatient services, both as a cost-efficient measure and as a competitive market strategy. Hospitals that divert internal resources to community care can reduce expenses in costly inpatient wards while expanding into the outpatient market. Also, it can be easier to expand an existing facility than to build a new one. A standing psychiatric hospital can develop a satellite community service at a lower start-up cost than a new market entrant can construct an independent facility. Further research could test which payment mechanisms and market conditions incentivize hospitals to diversify services.

Alternatively, a third set of explanations could explore the causal pathway from the opposite direction and through confounding variables. Reversing the hypothesis that the hospital promotes community care, it is possible that extensive outpatient services now sustain inpatient care, even if unintentionally. For example, community care teams surveying population mental health needs may identify more individuals requiring hospital attention. To that end, the positive correlation between community and hospital care may reflect a social commitment to expanding the mental health workforce trained to work in both settings. Other confounding factors include the capacities of the general health system, the design of the social welfare system, and the role of the civil and criminal justice systems.

Advocates and policy makers, too, should temper the assumption that a trade-off exists between inpatient and outpatient care. Achieving a top policy priority—a robust community care system—requires the destigmatization of the mental hospital. Allocating resources to hospitals can support this goal. This is not to say that trade-offs are absent in mental health. On the contrary, more attention should be paid to other distributive questions, such as how to allocate resources across psychiatric specialties, across health and social care services, or across segments of the workforce. The paradigmatic status of the hospital-versus-community exchange has eclipsed these important debates.

Increasingly, analysts are questioning the ethical and clinical implications of the assumed trade-off between inpatient and outpatient services (

11–

15). Besides, cross-national evidence suggests that the trade-off is empirically disputable. Community care and inpatient services appear to be complements, not substitutes. Substantial resources should be allocated to services along a coordinated, balanced continuum of mental health care, where both psychiatric hospitals and community psychiatric services offer critical points of service.