Disengagement From Early Intervention Services for Psychosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

HIGHLIGHTS

Methods

Search Strategy

Quality Assessment

Results

| Predictor and association with disengagement | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Setting | Design and sample | Definition of disengagement | Disengagement rate | Follow-up | Positive | Negative | None | OCCS scale ratingb |

| Kim et al., 2019 (15) | Melbourne; EPPIC | Cohort study; N=707 | Actively refused any contact with the treatment facility or were nontraceable | 53% | 24 months | Not being in employment, education, or training; cannabis use | Family history of psychosis in a second-degree relative | Age, sex, amphetamine abuse | High |

| Lau et al., 2019 (17) | Hong Kong; EASY | Cohort study; N=277 | Type I: continuous default despite therapeutic need and active tracing from staff; type II: continuous default and reengagement through hospitalization; type III: consecutive default from outpatient appointments and reengaged | Varied by definition: type I, 13%; type II, 4.3%; type III, 13.4% | Within the 3-year program | Type I: poor medication adherence; type II: poor medication adherence; type III: history of self-harm or suicide attempts, poor medication adherence, history of substance abuse | Type III: history of substance abuse | Type I: history of substance abuse, history of self-harm or suicide attempts; type II: history of substance abuse; type III: duration of untreated psychosis, forensic history | Medium |

| Maraj et al., 2019 (26) | Montreal; PEPP | Cohort study; N=394 | Considered to have disengaged from the service after 3 consecutive months of no clinical contact | About 20% at 12 months; no differences between groups | 24 months | Vocationally inactive on a sustained basis | None | Age, no contact between family and treatment team, substance use disorder, sex, material deprivation, duration of untreated psychosis, racial-ethnic minority status, social deprivation, functionality, symptoms, vocational activity at baseline | High |

| Hamilton et al., 2018 (21) | Texas; coordinated specialty care service | Mixed-methods research; N=129 | Retention operationalized as the likelihood of remaining in the program for ≥9 months | 41% | About 18 months | None | Home-based cognitive therapy, male sex | Age, severity of psychosis symptoms, case management, schizophrenia diagnosis | High |

| Maraj et al., 2018 (18) | Montreal; PEPP | Cohort study; N=297 | No clinic or community appointments with the psychiatrist or case manager and not responding to phone calls | 24.2%; mean±SD time to disengagement, 13.3±5.7 months | 24 months | General: medication nonadherence; among first-generation immigrants: age and medication nonadherence; among second-generation immigrants: material deprivation and medication nonadherence | None | General: immigrant status, age, sex, substance use, educational level, family contact, social deprivation, material deprivation; among first-generation immigrants: sex, substance use, educational level, family contact, social deprivation, material deprivation; among second-generation immigrants: age, sex, substance use, educational level, family contact, social deprivation | High |

| Solmi et al., 2018 (14) | East Anglia, United Kingdom; early intervention in psychosis services | Cohort study; N=786 | Considered to have disengaged after all possible ways to engage client had been explored over a 2- to 3-month period | 11.7%; median follow-up time of 15 months among those who left the program because of disengagement | Within 36 months | Male sex, age 30–35, duration of untreated psychosis of 5–8 weeks, no first-episode psychosis diagnosis, polysubstance misuse, hallucinations | Unemployment, severe psychomotor symptoms, poverty, first-rank delusions | Marital status, site | High |

| Rosenheck et al., 2017 (24) | United States; Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode–Early Treatment Program study | Cluster randomized controlled trial; N=404 | Minimal engagement was ≥3 contacts with the supported employment and education specialist over the course of the study | About 32% of NAVIGATE participants had <3 contacts with the supported employment and education specialist during the trial, compared with 76% of those in the control group | 24 months | None | Engagement in rehabilitative services | None | High |

| Casey et al., 2016 (31) | Birmingham and Solihull, United Kingdom; Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust early intervention services | Cohort study; N=103 | Results of the Singh O'Brien Level of Engagement Scale, which evaluates longitudinal disengagement, cross-sectional disengagement, and attendance at appointments | NA | 24 months | None | Lower education, beliefs about mental illness (caused by social stress and odd thoughts), longer duration of untreated illness | Sex, race-ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, marital status, biological explanation models, diagnosis, duration of untreated psychosis | Low |

| Chan et al., 2014 (28) | Hong Kong; EASY | Cohort study; N=700 | Continuous default of the EASY service despite therapeutic need and active tracing from staff for psychiatric follow-up | 5% at 6 months, 9% at end of first year, and 13% at end of second year | 24 months | Negative symptoms at baseline, schizophrenia spectrum disorder (versus other psychosis), medication compliance at baseline, substance abuse within first 6 months of program | None | Age, sex, years of education, age at onset, onset mode, duration of untreated psychosis, positive symptoms, social and occupational functioning, taking second-generation antipsychotic at baseline | Medium |

| Anderson et al., 2013 (8) | Montreal; PEPP | Cohort study; N=324 | No contact for a continuous period of 3 months | 28% (N=89) disengaged; median time to dropout, 5 months | 24 months | Older age, Black race-ethnicity | Living alone | Sex, material deprivation, social deprivation, substance abuse, symptom severity, police or ambulance contact, total contact | High |

| Macbeth et al., 2013 (30) | Scotland; early intervention psychosis services | Cross-sectional cohort study; N=64 | Engagement measured with the Service Engagement Scale | Service Engagement Scale mean total score, 9.48c | More than 12 months | Negative symptoms | None | Sex, academic premorbid adjustment, social premorbid adjustment, positive symptoms, general psychopathology | Medium |

| Zheng et al., 2013 (23) | Singapore; Early Psychosis Intervention Program | Cohort study; N=839 | Telephone contact with a family member only and no contact with client | 14%; telephone contact maintained with family only for 55 clients (7%); no contact for 54 clients (7%) | 24 months | Ethnicity (Malay group), education | None | Age, male sex, marital status, living alone, employment, duration of untreated psychosis, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general psychopathology | High |

| Stowkowy et al., 2012 (7) | Calgary, Canada; Calgary Early Psychosis Treatment Service | Cohort study; N=286 | Disengagement defined as program dropout before 30 months; those considered to be patients who dropped out did not return calls, could not be reached, or did not attend appointments for 3 months | 31% | Before 30 months | Schizophreniform diagnosis | Family member in program, negative symptoms, general psychopathology | Age, sex, premorbid functioning, duration of untreated psychosis, living alone, marital status, age at onset, functioning, quality of life, cognitive functioning, positive symptoms, drug use | High |

| Chen et al., 2011 (25) | Hong Kong; EASY | Case-control study; cases, 700 clients who received intervention from EASY between 2001 and 2003; controls, 700 persons who received standard care between 1998 and 2001 | Having no psychiatric contact at the end of the study | EASY, 23%; standard care, 30% | 24 months | None | Phase-specific early intervention (vs. standard psychiatric care) | None | Medium |

| Conus et al., 2010 (22) | Melbourne; EPPIC | Cohort study; N=786 | Active refusal of any contact with the treatment facility; the date of the last face-to-face contact between the case manager and the patient was considered the disengagement date | 23.3%; 11% within the first 6 months, 16% within first 12 months, and 26% within first 18 months | Within 18 months | Forensic history, no education or no employment, living without family, diagnosis of other psychosis (vs. schizophrenia), persistent substance use during treatment, living without family at discharge, severity of illness at discharge | Premorbid functioning (assessed with GAF), duration of prodromes (in months), severity of illness, functioning (GAF) at discharge | Sex, family history of psychosis, past psychiatric history, past substance use, history of sexual abuse, history of physical abuse, suicide attempts, duration of untreated psychosis (in weeks), age at onset, age at baseline, lack of insight, comorbid condition at baseline, including substance abuse | High |

| Turner et al., 2009 (19) | Christchurch, New Zealand; early intervention for psychosis service and outreach program | Cohort study; N=236 | Terminated treatment against clinicians’ advice | 34% | 24 months | Unemployment, substance use at baseline, functioning | None | None | High |

| Lecomte et al., 2008 (29) | Vancouver, Canada; early psychosis intervention | Cross-sectional study; participants admitted to the service; N=118 | Higher scores on the Service Engagement Scale, indicating difficulties in engagement | Almost 50% experienced difficulties engaging with the clinician or case worker | NA | Male sex, forensic history, childhood physical abuse, therapeutic alliance, knowledge regarding consumer rights, low neuroticism, high agreeableness | None | Insight, substance use | Medium |

| Turner et al., 2007 (16) | Christchurch, New Zealand; early intervention for psychosis service and outreach program | Cohort study; participants admitted to the service; N=232 | Termination of treatment despite therapeutic need | 24.6%; those who self-discharged were considered “disengagers” (N=39) | Within 12 months | Duration of untreated psychosis, current substance use | Insight, illness severity, diagnosis of mood disorder | Sex, living with parents, ethnicity (Maori), employment, inpatient admissions, compulsory admissions, police contact, age, interpersonal relations, quality of life, positive symptoms | High |

| Schimmelmann et al., 2006 (20) | Melbourne; EPPIC | Cohort study; sample drawn from a larger cohort treated at EPPIC between 1998 and 2000; N=134 | Actively refused any contact with the treatment facility or was not traceable | 23% | Within 18 months | Living without family | Severity of illness | Diagnosis, functioning, substance use | High |

| Garety and Rigg, 2001 (27) | South London, United Kingdom; South London and Maudsley National Health Service Trust | Cohort study; all presentations of first- and second-episode psychosis in a defined catchment area; N=21 | Nonengagement recorded when the person was refusing contact or was lost to any contact with mental health services | 40% | 12-month assessment | None | None | None | Medium |

Methodological Characteristics

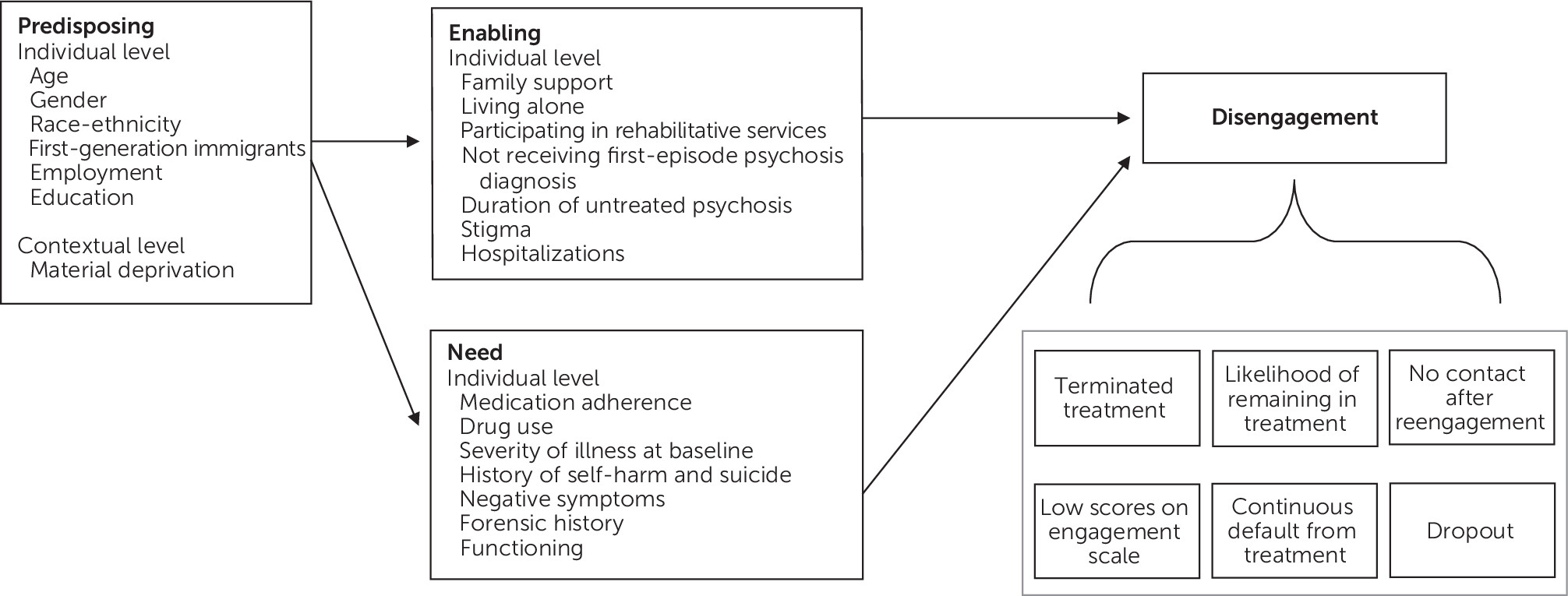

Predictors of Disengagement

Predisposing factors.

Enabling factors.

Need factors.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Interpretation of Findings

Strengths and Limitations

Future Studies

Conclusions

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 438.24 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).