Bipolar disorders often present initially in primary care, especially bipolar disorder II and subthreshold forms of the disorder (

1). Psychiatry has historically offered little direct assistance to primary care providers, but in the past decade the advent of the collaborative care model (CoCM) is changing this relationship (

2). The CoCM utilizes embedded behavioral health professionals supported by psychiatric case consultation to provide evidence-based, measurement-based treatment-to-target (

3).

In early iterations of the CoCM, the prevalence of bipolar disorders in primary care was thought to be low (

4). However, more recent investigations have suggested that bipolar disorders are common among patients referred for psychiatric consultation (

1,

5). Yet even among specialists, multiple controversies persist regarding the diagnostic boundaries of bipolarity. Although underdiagnosis of bipolar disorder has been documented (

6), particularly in primary care (

7,

8), concerns about “overdiagnosis” have received perhaps even more attention (

9,

10) (and subsequent refutation (

11)). Multiple mood specialists have suggested that a dimensional approach—acknowledging a spectrum of mood from unipolar to bipolar, with no line to be over or under—better fits observations. Proponents include the

DSM-5 Task Force Chair (

12) and other highly respected mood specialists (

13–

15). The boundaries of bipolar mixed states are also vigorously debated (

16).

Aware of these diagnostic controversies, Samaritan Mental Health (SMH) designed a variation of the CoCM that includes screening for bipolarity of all referred patients (

17). In keeping with the practice of many CoCM programs (

18), SMH uses the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0 (CIDI), a structured interview that elicits a history of symptoms of mania (

19). SMH also uses an unpublished questionnaire that gathers data on non–mania-related markers (

15,

20,

21) of bipolar disorder: family history, age of onset, course of illness (number of episodes, postpartum onset, psychosis), and response to treatment (including symptoms of hypomania that were induced by antidepressants). Findings are assessed by a psychiatrist who offers a written diagnostic impression.

However, universal screening carries a risk of overdiagnosis (

22). When a clinician’s suspicion of bipolar disorder initiates screening, this process—selecting for testing only patients who already exhibit some sign of bipolarity—enriches the prevalence of bipolar disorders. As a result, the risk of false positives is decreased, because prevalence has a strong effect on a test’s positive predictive value (

23). By contrast, when all referrals are screened for bipolar disorder, false positives will be more common. Case-by-case assessment of findings by a psychiatrist, as in the SMH program, should minimize this risk. However, SMH seemed to be identifying a high percentage of referrals as “bipolar” (

5). Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis of bipolar diagnosis and associated outcomes after CoCM psychiatric consultation.

We expected to find, first, a higher prevalence of bipolar disorder than previously reported, such as the 3%–9% rate found in a 2013 review (

24); second, a smooth distribution of scores on the CIDI, supporting dimensional diagnosis; third, that consultants using markers of bipolar disorder other than mania (e.g., family history, age of onset, course of illness, response to treatment) would identify more patients as “bipolar” than would the CIDI cutoff; and fourth, that patients thus identified (potentially “overdiagnosed”) would not have poor outcomes compared with other patients who were presumably correctly diagnosed.

Methods

Program

We developed a variation of the CoCM to fit our local needs and strengths (

17). All patients referred for psychiatric consultation in our system receive a structured interview conducted by a mental health specialist (MHS). The interview includes the baseline Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 questionnaire (GAD-7), the CIDI, 12 questions regarding non–mania-related markers statistically associated with bipolar disorders (e.g., family history, age of onset, course of illness, and response to treatment), a brief trauma screen (the Primary Care PTSD Screen) plus questions about childhood and adult trauma, and other questions that are routine for an initial psychiatric interview. Resulting narrative and numerical data are forwarded electronically to a psychiatrist, who adds an “Impression” and recommendations in the electronic health record (EHR) consultation note. At intervals dictated by clinical needs, the MHS conducts follow-up interviews, which include repeat completions of the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7.

In our EHR system, consultants chart Impressions, not formal diagnoses, because with rare exceptions, the consultants have not seen the patient. Interpretations of bipolarity are based on the data that are available at the time of the initial consultation: the MHS’s narrative in the History of Present Illness section of the EHR, the CIDI results, responses to questions about bipolar markers, and a review of relevant data in the record. Consultations are written by attending physicians and fourth-year psychiatry residents.

Our consultants convey their formal recommendations electronically directly to primary care providers for consideration and implementation, as advocated in a recent review of CoCM best practices (

25). MHSs monitor communications to ensure that these recommendations are reviewed and acted on. Consultants recommend psychotherapies as well as medications, although therapy access is extremely limited for much of our population, especially patients from rural areas and those with Medicare insurance.

Study Population

Our institutional review board reviewed this study and approved it as exempt research. During the period between March 2018 and October 2019, we reviewed all CoCM referrals for patients with a consultation visit between January 1, 2015, and May 1, 2019, and selected patients who had a PHQ-9 score >10 at the time of consultation or within 3 months prior, who were at least 18 years of age, and who were administered at least one follow-up PHQ-9 in the 6 months after consultation (thereby narrowing the pool from all referred patients to those with significant depression and available follow-up PHQ-9 results). Because patients’ response to lamotrigine or low-dose lithium was our primary interest during the design of this review, patients who had received these medications before their consultation—per the 6-year EHR—were excluded. (Further history regarding this exclusion is presented in an online supplement.)

Measures

From the EHR, we extracted patients’ demographic data and insurance information as a rough indicator of socioeconomic status.

In keeping with the practices of several CoCM programs (

26), we used the PHQ-9 (

27) to quantify depression severity and follow changes over time. PHQ-9 responses were generally obtained on the day of the MHS interview beginning the consultation process (in some cases, up to 3 months previously). Follow-up PHQ-9s were administered at intervals dictated clinically. In this analysis, we divided follow-up data into two time frames: 0–3 months and 3–6 months after consultation, presuming that the shorter time frame might indicate acute treatment responses and the longer time frame might offer a glimpse at the sustainability of that response. In each of those two follow-up time frames, when multiple PHQ-9 scores were available, the lowest score was used.

The CIDI is a nine-question survey of symptoms of mania, administered if two of three screening questions are positive (

28). A cutoff for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder of ≥7 has been used in previous CoCM studies (

18,

29). In our system (as in some iterations of the CoCM), consultants were not bound to a categorical (yes-no) CIDI score interpretation.

Questions regarding non–mania-related markers of bipolar disorder (e.g., family history, age of onset, and 10 other questions about course of illness and response to treatment) (

15,

20,

30) were derived from the Bipolarity Index (

31), a tool developed for the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder research program (

14). Family history was screened by using a check-box system previously shown to improve performance on the Mood Disorders Questionnaire (

32). Previous use of psychotropic medications, per the patient’s recollection, was assessed by observing the number of medications the patient circled on a list of common antidepressants and other psychotropic medications. (A complete three-page questionnaire is available in an

online supplement.)

By manual chart review, we retrieved CIDI scores from the MHS consultation note (our EHR does not encode these results) and consultants’ Impressions, characterizing them for this analysis as no bipolarity (Impression negative) or possible/probable bipolarity or prior formal diagnosis (Impression positive).

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated to describe the demographic characteristics of the study population and explore patterns of psychiatric consultant Impressions and CIDI scores. With a categorical interpretation of the CIDI, patients could be classified as positive (≥7) or negative (<7). Likewise, consultant Impressions could be negative or positive. Thus, four groups emerged from these measures: two diagnostically concordant (CIDI positive–Impression positive and CIDI negative–Impression negative) and two discordant (CIDI negative–Impression positive and CIDI positive–Impression negative).

Because of nonnormally distributed data and concerns of unequal variance due to unbalanced group sizes, we used Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum tests to determine whether these diagnostic groups significantly differed in change of PHQ-9 score over time. Pairwise comparisons were then performed via Mann-Whitney U tests. All analyses were performed in R, version 3.6.1.

Discussion

In this study, we found, as expected, a high prevalence of bipolarity compared with that found in previous reports, a smooth distribution of scores on the CIDI, that psychiatric consultants identified more patients as having bipolarity than the CIDI did, and that patients thus identified (potentially “overdiagnosed”) did not have poor outcomes relative to those of other patients who were presumably correctly diagnosed.

Our program demonstrates that bipolar screening for all patients referred for consultation is feasible within the CoCM model. The CIDI was administered to 97% of referred patients. By contrast, in one study when screening was left to clinician discretion, only 15% of patients with depression (according to PHQ-9 scores) were screened for bipolar disorder with the intended instrument, the CIDI (

29).

Routinely obtaining data on markers other than mania (family history, age of onset of depression, course of illness, and response to treatment) also is feasible. Our questionnaire was completed by 94% of referred patients. This routine allows interpretation of CIDI results in the context of other data that affect the prior probability of bipolar disorder (

20,

23). In theory, this substantially increases the positive predictive value of a bipolar impression (

23). Increasing predictive value decreases the risk of overdiagnosis; however, careful analysis of risk-benefit ratios for treatments associated with different diagnostic interpretations remains essential.

As expected, the prevalence of bipolarity in patients with depression in our version of the CoCM was high: 21% by CIDI using a cutoff of ≥7 and 35% by consultant impression. These rates are much higher than the 3%–9% rates found in studies using a structured interview (

24), higher even than the 20%–30% found in studies using a screening questionnaire such as the Mood Disorders Questionnaire (

7). However, unlike in previous studies, our patients were highly selected; they were referred for psychiatric consultation, often after years of attempted treatment in primary care.

We have shown that patients who were referred for consultation in our system have used an average of eight prior psychotropic medications, including an average of 2.8 prior antidepressant trials (

5). Referrals constitute a group that has not responded to primary care management, one subgroup of which is likely to have unrecognized bipolar disorder (

8,

34). Thus, the frequency of bipolar disorder is enriched relative to the broader primary care population, a “bipolar sieve” effect (

5).

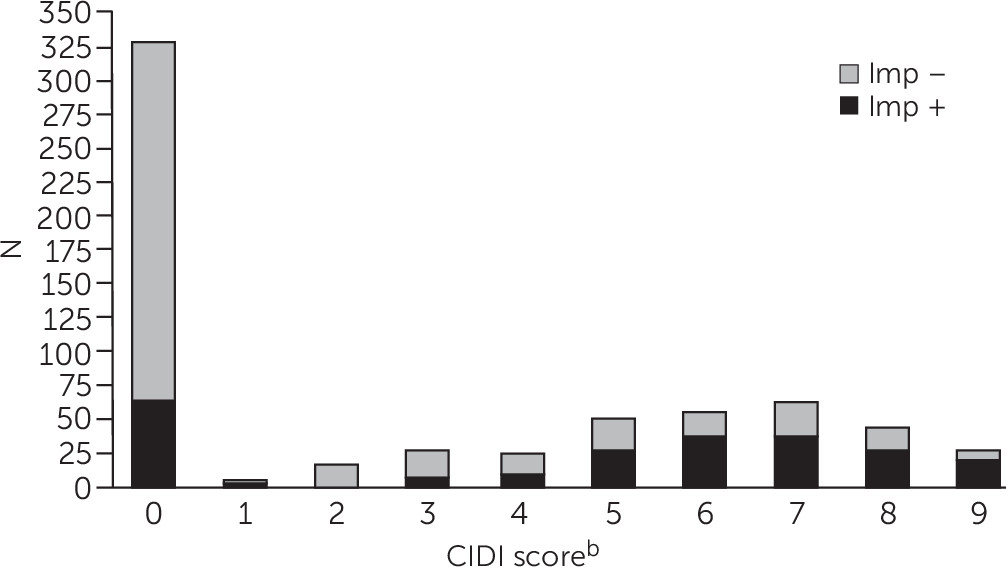

Our second expectation, a smooth distribution of CIDI scores, was also observed (

Figure 1). In our sample, 107 of 641 (17%) had a CIDI score of 5 or 6, just below the usual cutoff (≥7). Consultants’ Impressions were positive for 64 of these 107 patients (60%). By comparison, among patients with a positive CIDI (≥7), consultants’ Impressions were positive for 55%. Thus, consultants were just as likely to arrive at a “bipolar” Impression for patients with scores just below the cutoff as for those with scores above it. The smooth distribution of scores argues against a categorical yes-or-no interpretation of the CIDI.

Our third expectation, that psychiatric consultants would identify more patients with bipolarity than the CIDI would, was also observed (

Table 2). This finding could be the result of the following: a broader interpretation of bipolarity, the availability of data on nonmania markers (likely the basis for bipolar impressions in patients with CIDI scores of 0, for example), or access to data from the EHR (hospitalization records, details of prior medication responses, etc.).

Consultants’ diagnostic divergence from the CIDI invites the question, Is this “overdiagnosis” as per previous concerns (

9,

10)? Within a categorical model, that question is usually addressed by comparison with a diagnostic gold standard—historically, a structured interview (the validity of which has been questioned) (

11,

35). In the absence thereof, patient outcomes might provide an indirect indication of diagnostic accuracy. This leads to our final expectation: that patients who were potentially “overdiagnosed” would not have poor outcomes relative to other patients presumably correctly diagnosed.

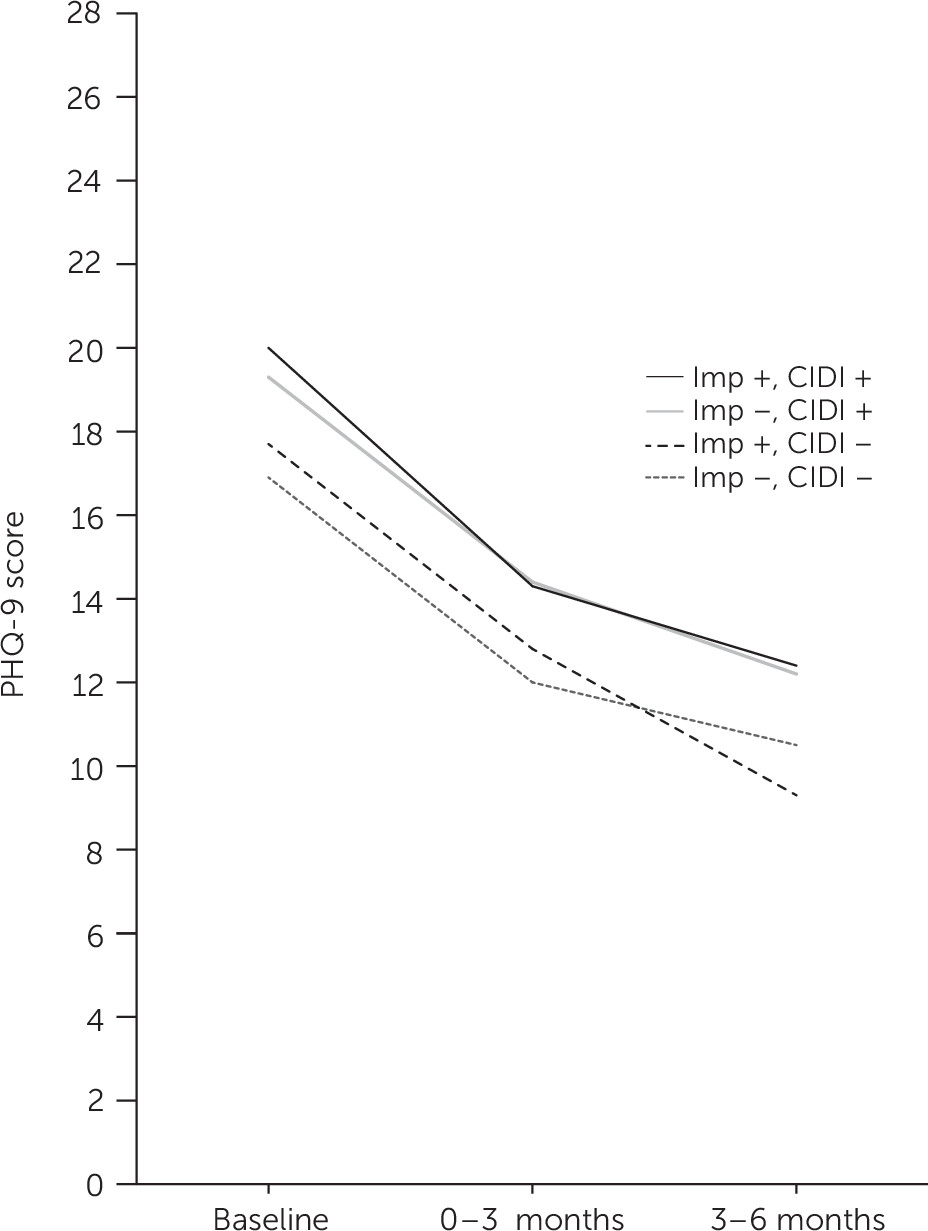

As shown in

Figure 2, all four groups improved at the same rate. Potential explanations are as follows: first, diagnosis may matter little if the bulk of improvement in our CoCM program represents regression to the mean or the effect of nonspecific factors (referral, interview, follow-up attention). Second, diagnoses can be wrong, yet treatments offered can still be effective. Lithium can be particularly helpful in treating unipolar depression (

36) as well as bipolar depression (

37). Third, consultants’ bipolar impressions could have been correct, with outcomes equivalent to those of other correct assessments. Examining CoCM outcomes on the basis of treatments received, rather than diagnosis, might help sort between these potential effects.

Limitations of this study include the paucity and irregularity of follow-up administrations of the PHQ-9. Some patients had only one follow-up PHQ-9 score, and the timing of repeat questionnaires was variable. We report the lowest follow-up PHQ-9 scores in each 3-month interval, but some patients may have worsened later within that interval. Because of a smaller sample size for PHQ-9 scores in the 3- to 6-month time frame, confidence intervals regarding differences in scores between diagnostic groups were much wider than for differences in the 0- to 3-month time frame (7 points versus 2 points, respectively, where the clinically significant difference is thought to be about 5 points on the PHQ-9 scale [

27]). Further, our study population is racially narrow—as is typical in the rural Pacific Northwest United States (

38)—although socioeconomically diverse (as reflected by insurance;

Table 1). Generalizability to other populations and to primary care systems in other countries may be limited. Finally, our focus in this study was also narrow. Although substance use, anxiety symptoms, and personality measures are assessed in our CoCM interviews, we did not examine either their effects on outcomes or the effects of trauma exposure.