Premature death is a major concern for individuals with mental illness (

1). Nearly one in seven deaths worldwide may be attributable to mental illness (

2). Individuals with schizophrenia are reported to die as many as 25 years earlier than people in the general population (

3). This finding is not limited to individuals with schizophrenia or other serious mental illnesses. Using a nationally representative survey of the United States, Druss and colleagues (

4) found that individuals with any self-reported mental disorder were on average 8 years younger at death than members of the general population. Those with mental illness died at twice the rate of those without mental illness, although this association of increased mortality rates with mental illness became nonsignificant after adjustment for baseline clinical characteristics, socioeconomics, and health system factors (

4). Similarly, a meta-analysis of all-cause mortality found a pooled relative risk of 2.22 for those with mental disorders relative to those without these disorders and a median of 10 years of potential life lost (

2).

The association between mental illness and increased mortality risk varies across diagnoses. A meta-review of all-cause mortality associated with mental disorders found the highest levels of excess mortality for substance use disorders and anorexia nervosa and the lowest for dysthymia (

5). A 2015 meta-analysis that did not include substance use disorders found pooled relative risks of 2.54 for psychoses, 2.08 for mood disorders, 2.00 for bipolar disorder, 1.71 for depression, and 1.43 for anxiety (

2).

Roughly two-thirds (67.3%) of deaths among individuals with mental illness are estimated to be due to natural causes, with 17.5% being due to external causes and the rest unknown (

2). Much of this excess mortality is attributable to general medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes (

3,

6), rather than either mental illnesses directly or causes such as suicide or overdose that are closely associated with mental illness. An analysis of >1.7 million deaths among primary care patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) found that, both for patients with and without mental illness, most deaths were due to heart disease and cancer (

7). Reducing excess mortality for people with mental illness in the United States will require enhanced access to care, better primary care, treatment for chronic conditions, and promotion of healthy behaviors and environments (

2,

8).

Generally weak associations have been observed between VHA facility–level process-based quality indicators and mortality for general medical conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia (

9). However, patients in the VHA were found to have a lower 30-day mortality rate after acute myocardial infarction and heart failure than patients in non-VHA hospitals, which may be attributable to greater adherence of VHA hospitals to process-based quality measures (

10). Also, in the VHA, receipt of appropriate care is associated with a lower mortality rate for patients with substance use disorders (

11,

12).

In 2005, VHA patients with serious mental illness had an average of 13.8 years of potential life lost, versus 12.3 years for patients without mental health diagnoses (

13). This mortality gap among VHA patients was considerably smaller than the 25-year gap reported for individuals with schizophrenia in the general population (

3). This smaller mortality gap may be attributed partly to the fact that VHA is an integrated health care system providing medical and mental health care in inpatient and outpatient settings (

13).

Although excess mortality has been established across diagnoses, little is known about the extent to which it varies across health systems or facilities because of differences in the care provided or community factors that affect mortality rates. In other medical fields in which it is standard practice to track and report patterns and correlates of increased mortality, such as cancer and cardiac surgery, substantial gains have been made in patient survival in recent decades (

14,

15). We hypothesized that the same may be true for mental health, where we currently know of no systematic efforts to track and report mortality rates, either by facility or overall (

16). Variation in excess mortality rates by facility, especially variation that is consistent over time, may reflect variation in health care quality and thus help guide and encourage quality improvement efforts. It may also be a proxy for community factors that affect mortality and which might be the focus of additional prevention and intervention efforts within and beyond health care.

The purpose of this analysis was to examine whether and how excess mortality for individuals with mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses who receive VHA care varies across VHA facilities and psychiatric diagnosis groups. We also assessed the test-retest reliability of the facility-level measures of excess mortality to determine the extent to which they may be influenced by random variation over time.

Methods

The analyses in this study were conducted as part of ongoing VHA quality improvement efforts, and institutional review board approval was not required. Data on health care encounters and diagnoses were obtained from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse in August 2019. Mortality statistics for VHA users were obtained from the Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Mortality Data Repository, which includes comprehensive search results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Death Index (

17).

To identify recent VHA users and their mental health diagnoses, we constructed six annual cohorts from 2011 to 2016 of VHA users who were alive on January 1 of each year and had received inpatient or outpatient VHA services in the previous year. Patients were counted at their facility of last use, and those alive at the end of the year were censored. Multiple years were combined for analysis. Thus, only recent VHA users were included, and patients who had no VHA care for >1 year were removed from the analysis.

Mental illness was defined at baseline for each year on the basis of diagnoses recorded in the previous year. The diagnoses were based on

ICD-9 codes before October 1, 2015, and

ICD-10 codes thereafter. The following diagnoses were recorded: serious mental illness (i.e., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and other psychoses and bipolar disorder), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, substance use disorders (excluding tobacco), and any mental or substance use disorder. These diagnoses were selected because of their high prevalence among VHA users and previously reported associations with increased mortality rates (

2,

5,

18). In all analyses, the VHA population with no mental or substance use disorder diagnoses represented the reference group.

Serious mental illness was defined with ICD-9 codes 295.0–295.4, 295.6–295.9, 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.8, 297.0–297.3, 297.8, 297.9, 298.0–298.4, 298.8, or 298.9 or with ICD-10 codes F06.0, F06.2, F20, F22–F25, F28–F31, or F53. PTSD was defined with ICD-9 code 309.81 or ICD-10 codes F43.10–F43.12. Major depressive disorder was defined by the ICD-9 codes 296.2 or 296.3 or ICD-10 codes F32.0–F32.5, F32.9, F33.0–F33.3, F33.40–F33.42, or F33.9. Substance use disorder was defined with ICD-9-CM codes 291, 292, 303.0, 303.9, 304.0–304.6, 304.8, 304.9, 305.0, or 305.2–305.9 or ICD-10 codes F10–F16, F18, or F19. Any mental or substance use disorder was defined by ICD-9 codes 290.8–294.0, 294.9–305.0, or 305.2–320 or ICD-10 codes F06.0, F06.2–F06.4, F10–F16, F18–F24, F25.0, F25.1, F25.8, F25.9, F28, F29, F30.1–F30.4, F30.8, F30.9, F31–F34, F39, F40.0, F40.2, F40.8–F40.11, F41.0, F41.1, F41.3, F41.8, F41.9, F42, F43.0–F43.2, F43.8, F43.9, F44, F45, F48.1, F50.0, F50.2, F50.8, F50.9, F53, F60, F63, F68.1, F68.8, F69, F90, F91, or R45.7.

State-level, age-adjusted (to the year 2000 standard population) all-cause adult mortality rates were obtained from the CDC WONDER website (

19) for 2011–2016.

For the combined 2011–2016 cohorts, we calculated facility-level all-cause mortality rates for all 139 VHA facilities in the 50 United States and Washington, D.C. (i.e., not including VHA facilities in the Philippines or Puerto Rico), directly standardized to the overall sample’s age (categorized as 18–54, 55–74, and ≥75 years) and sex distribution. These facilities may consist of a medical center as well as any associated outpatient clinics. We assessed the Spearman rank-order correlation between these facility rates and the age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate for the state in which the facility is located.

PROC PHREG in SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.15, was used to fit Cox proportional hazards models for each diagnosis. We calculated facility-specific hazard ratios (HRs) comparing VHA users having received mental or substance use disorder diagnoses with those without such diagnoses by including an interaction term between diagnosis and facility. These models, fitted separately for 2011–2013 and 2014–2016, were adjusted for age, sex, facility, and revised Charlson comorbidity index (

20). To determine the reliability of the measure of excess mortality over time, we divided the analysis into two periods (2011–2013 and 2014–2016) and assessed correlations between facilities’ earlier and later HRs.

To assess whether facility-level excess mortality for patients with one type of mental illness was associated with excess mortality for patients at that facility with other categories of mental illness, we assessed Spearman rank-order correlations between facility-specific HRs across diagnostic groups. Although mental illness is rarely a direct cause of death, to assess death that may be associated with medical care for patients with mental illness, rather than deaths that may be attributable to the mental illness itself, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that censored deaths from suicide and drug or alcohol overdoses.

Results

The characteristics of the study population in their first year of inclusion are shown in

Table 1. Across all years, data from 8,812,373 unique individuals were included in the analysis; 7,777,553 (88.3%) were men and 1,034,820 (11.7%) were women. In the first year of inclusion, 14.7% were 18–34 years old, 23.3% were 35–54 years old, 42.9% were 55–74 years old, and 19.1% were 75–115 years old. The number of people included increased from 5,350,490 in the 2011 cohort to 5,853,024 in 2016. Most (67.3%) had no psychiatric diagnosis in the previous year. The prevalence for each psychiatric diagnosis category was 3.7% for serious mental illness, 9.8% for PTSD, 5.4% for major depressive disorder, 4.6% for other mental health conditions, and 9.3% for substance use disorders. The mean± SD Charlson score was 0.83±1.41. The mean±SD facility-level, age- and sex-standardized all-cause mortality rate for 2011–2016 was 3,299±262 per 100,000 person-years. Facility all-cause mortality rates were statistically significantly correlated with the all-cause mortality rates of the states in which they were located (Spearman r=0.55, p<0.001).

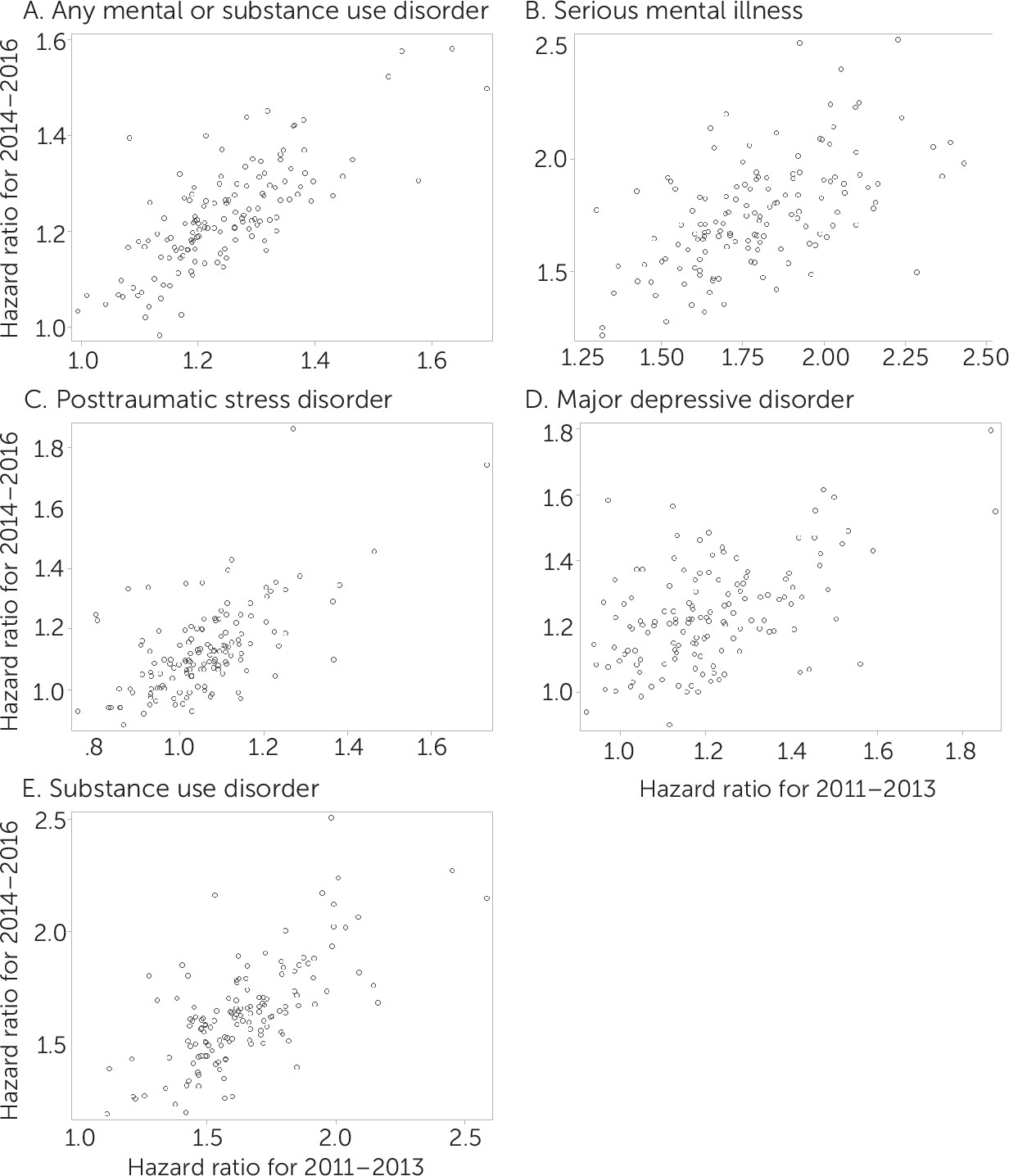

Facility-level HRs comparing VHA patients with or without any psychiatric diagnosis for 2011–2013 were significantly correlated with HRs for 2014–2016 (

Figure 1, r=0.75, p<0.001). This was also true for each diagnostic category. By diagnostic category, the HR correlations were 0.56 (p<0.001) for serious mental illness, 0.62 (p<0.001) for PTSD, 0.51 (p<0.001) for major depressive disorder, and 0.69 (p<0.001) for substance use disorder.

Excess mortality varied by psychiatric diagnosis. For VHA overall, the mortality rate among patients with any mental or substance use disorder was 21% higher (HR=1.21, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.20–1.22) than the rate for patients without such diagnoses. By diagnostic group, the HRs were 1.71 (95% CI=1.69–1.73) for serious mental illness, 1.10 (95% CI=1.09–1.11) for PTSD, 1.21 (95% CI=1.20–1.21) for major depressive disorder, and 1.59 (95% CI=1.58–1.61) for substance use disorder compared with patients with no mental or substance use disorder diagnosis.

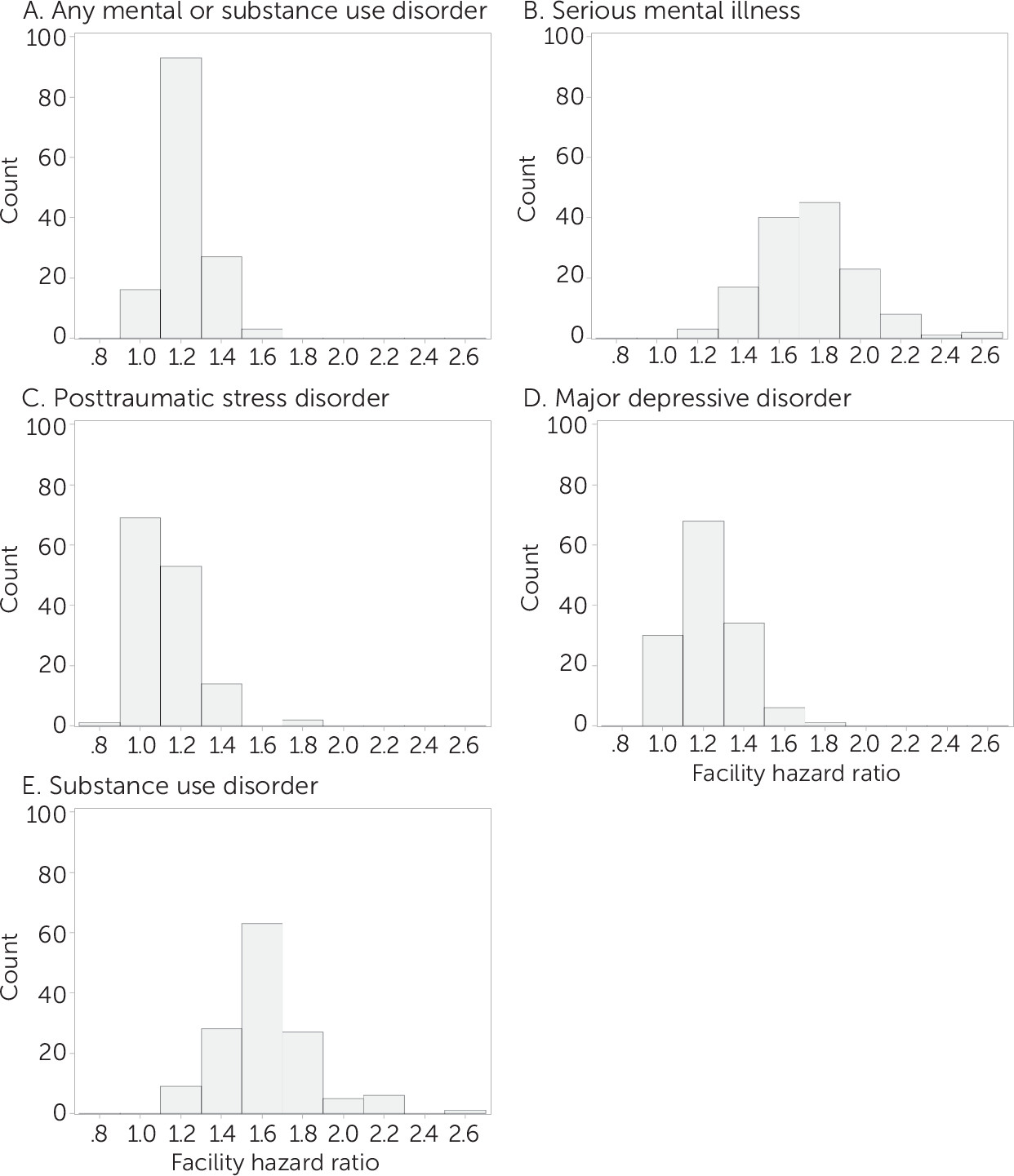

The HRs substantially varied across facilities, particularly for patients with a serious mental illness or substance use disorder. The facility mean±SD HRs were 1.75±0.24 for serious mental illness, 1.13±0.15 for PTSD, 1.23±0.16 for major depressive disorder, and 1.63±0.23 for substance use disorder. Histograms of the facility-level HRs for the 2014–2016 period are presented in

Figure 2. Within facilities, HRs of all mental health diagnoses were significantly correlated with each other (

Table 2). The strongest correlation was between PTSD and any mental or substance use disorder (r=0.82). Age-adjusted state mortality rates were significantly correlated only with an excess mortality for substance use disorders (r=0.31).

In the sensitivity analysis in which deaths from suicide and drug or alcohol overdoses were censored, substantial mortality gaps remained for patients with mental health and substance use disorder diagnoses. The overall HRs were 1.184 (95% CI=1.177–1.191) for any mental or substance use disorder, 1.63 (95% CI=1.61–1.65) for serious mental illness, 1.05 (95% CI=1.04–1.06) for PTSD, 1.14 (95% CI=1.13–1.16) for major depressive disorder, and 1.50 (95% CI=1.49–1.52) for substance use disorder. Findings on differences across facilities were not affected by censoring these deaths.

Discussion

Age- and sex-adjusted mortality rates at the VHA facility level were significantly correlated with the state-level all-cause mortality rate, suggesting that the same state-level factors influence death among VHA users and the general population. This finding supports the use of HRs to measure excess mortality because the reference group, patients with no mental or substance use disorder, are representative of the source population of VHA patients. Being an internal comparison, this method also controls for facility- and community-level factors that affect mortality rates for patients with and without mental illness.

The strong and significant correlations between VHA facility–level HRs in both the early and the later periods indicates that facility-level differences in mortality between patients with and without mental and substance use disorder diagnoses were stable over time. The differences observed across facilities may have been due to differences in the patient population that were not adjusted for, in the care received by these patients, or in the communities in which they live.

Excess mortality was greatest for patients with serious mental illness, followed by substance use disorder, major depressive disorder, and PTSD. This finding is largely consistent with those of previous studies that have reported large mortality gaps for psychoses and substance use disorders (

2,

5). Previous studies have reported excess mortality for veterans with a high probability of PTSD compared with veterans with a low PTSD probability (HR=2.27, p=0.002); however, this difference became nonsignificant after adjustment for demographic characteristics (

21). Additionally, that analysis was not limited to VHA users and so may reflect excess mortality among veterans with PTSD in the community, rather than in the VHA system. Differences from previous findings (

2,

5,

22,

23) may reflect high morbidity rates among our reference population (

24), participants’ ongoing health care, or overadjustment for comorbid general medical conditions.

Excess mortality varied substantially across VHA facilities. For patients with PTSD, for example, the facility-level HRs ranged from 0.88 to 1.86, indicating a range of outcomes, from patients with PTSD having lower mortality rates than patients with no mental or substance use disorder to patients with PTSD having 86% greater mortality rates than patients with no mental or substance use disorder. This variation, and the observation that facility-level HRs were correlated across both time and diagnoses suggests that these findings may provide meaningful new insight into excess mortality for patients with mental illnesses. Knowing how excess mortality varies across facilities represents a first step toward identifying facility-level characteristics, such as mental health quality measures or staffing ratios, that may be associated with reduced mortality. Despite routine reporting of hospital-level mortality for medical procedures, we know of no other work demonstrating facility differences in mortality for patients with mental illness.

At the facility level, excess mortality was correlated across diagnosis groups, such that having a higher HR for one psychiatric diagnosis category was associated with having higher HRs for all other psychiatric diagnosis categories. This observation adds validity to the assertion that characteristics of the facility, the patient population, and the community where the facility is located all influence excess mortality among patients with mental illnesses at that facility.

This study used data on mental health diagnoses routinely collected for health care operations, which may contain misclassifications. If patients with mental illness did not receive treatment for that mental illness in the VHA system, they may have been included in the category of no mental health or substance use disorder. Such misclassification would bias the observed HRs toward zero. Another limitation of the study was that there may have been unobserved differences between patients with and without mental diagnoses that have led to any observed differences in mortality. We did control for age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index scores, which are known to strongly predict 1-year mortality.

Unintended consequences of using excess mortality as a quality indicator could include focusing on mortality to the exclusion of other patient-centered outcome measures, such as symptom reduction or patient satisfaction. Another possibility is that, in order to artificially improve performance on such a measure, facilities may underdiagnose mental health conditions among patients with terminal illnesses. The potential benefit was a measure that may help identify facility and community factors associated with better outcomes for patients with mental illness. Documentation of death is relatively complete and unambiguous, supporting its utility as an outcome measure in many settings (

16). Further work is necessary to determine the extent to which facility-level variation is attributable to characteristics under the control of the facility versus differences in case-mix or community characteristics.

In sensitivity analyses, we censored individuals who died from suicide or drug overdoses. Although the HRs for diagnostic groups in this sensitivity analysis were slightly attenuated compared with the main findings, they confirmed that excess mortality for the population and the differences between facilities were driven by deaths from natural causes and not solely by higher suicide or overdose rates among individuals with mental illness.

Conclusions

VHA patients with mental or substance use disorders are at increased risk for early death compared with VHA patients without such diagnoses. The amount of excess mortality varied across facilities in the VHA health care system. Within a facility, the amount of excess mortality was consistent over time and was correlated across different mental and substance use disorder diagnoses. Excluding deaths from suicide or drug overdose did not substantially attenuate these gaps, suggesting that natural causes of death are responsible for most of the mortality gaps.

Further research is necessary to explore community- and VHA facility–level factors that may explain these gaps. These could include measures of the quality of mental health and medical treatment as well as indicators of community stressors, such as income inequality, unemployment, social capital, and the availability of mental health treatment in the community. This additional information may inform clinical and public health strategies to reduce the disparity in mortality rates for patients with mental and substance use disorders.