Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a pressing mental health concern among U.S. veterans, with prevalence estimates around 23% for veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) (

1). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system provides a variety of treatment services for veterans with PTSD, including residential rehabilitation treatment programs (RRTPs) and has made optimizing care for individuals with PTSD a high priority (

2). The purpose of this study was to examine racial disparities in clinical outcomes of VA PTSD RRTPs.

Racial disparities in disease burden and differences in the quantity and quality of health care between Black and White Americans are significant long-standing public health concerns (

3). Racism, discrimination, limited economic resources, segregation, restricted housing opportunities, chronic stress, and many other variables contribute to poorer mental and general medical health and restricted health care for Black Americans (

4). Furthermore, widespread unequal treatment of Black patients by non-Black health care providers has been well documented (

5). The VA is a unique health care system in that financial barriers to accessing private-sector health care (e.g., insurance coverage, income), which disproportionately affect Black Americans, are not directly present (

3,

6). Nonetheless, racial disparities in clinical outcomes and receipt of health care across a range of VA clinical services (e.g., heart and vascular disease, preventive and ambulatory care, mental health, and substance use) have been identified (

6). Current examinations of disparities in mental health treatment for veterans are needed to inform optimal care for individuals with PTSD.

The research literature has indicated higher prevalence and severity of PTSD among Black relative to White veterans. Black veterans who recently ended active duty military service (within the past 90 days) were more likely to screen positive for PTSD (36.3%) than were any other racial-ethnic group, including White veterans (22.5%) (

7). Compared with White counterparts, Black veterans were also more likely to screen positive for PTSD in a population-based cohort of OEF/OIF veterans (

8). Black active duty service members reported more severe PTSD symptoms (

9), and Black Vietnam War veterans have shown elevated rates and severity of PTSD compared with White veterans (

10,

11). However, one study of OEF/OIF veterans and veterans of Operation New Dawn (OND) found higher rates of PTSD for Black men but not for Black women (

12), and, in a sample of veterans from service eras before OEF/OIF/OND, no differences in PTSD by race were reported (

13).

Studies have also reported racial disparities in access to and receipt of mental health treatment for veterans with PTSD, although results have been mixed. Black veterans with PTSD were less likely to receive a minimally adequate dose of pharmacotherapy (i.e., 120 days of antidepressants) and any treatment in the 6 months after diagnosis. This disparity remained when accounting for personal beliefs about mental health treatment (

14). Other studies have corroborated that Black veterans with PTSD are less likely to receive any therapy (

15), individual therapy (

16), or a minimally adequate dose of treatment (at least nine mental health outpatient visits within a 15-week period or at least 12 consecutive weeks of medication use) within the first year of initiating treatment (

17) or a medication trial (

18); less likely to complete PTSD treatment (

19); and experience longer wait times before their first appointment (

20). Alternatively, some studies have indicated that Black (compared with White) veterans with PTSD are more likely to receive counseling (

18) and a greater number of psychotherapy appointments (

21) and that Black men were more likely than White men to use outpatient mental health care (

22).

Similarly, research remains mixed in terms of clinical outcomes of PTSD treatment among Black veterans. Lester and colleagues (

19) noted that Black veterans had PTSD treatment response similar to that of White veterans. This finding was similarly upheld within a sample of Black and White veterans receiving treatment for military sexual assault–related PTSD (

23). However, these prior evaluations were within the context of clinical trials, most of which have not reported outcomes by racial groups and differ contextually from routine clinical practice.

When the role of race on treatment outcomes was analyzed within real-world samples, differing results were reported. In a national study of clinical outcomes 6 months after receiving a PTSD diagnosis, Black veterans were less likely than White veterans to show significant improvement in PTSD symptoms (

24). This was true among both treatment initiators and noninitiators, indicating that differences in treatment initiation were not driving this disparity. These findings are consistent with other national studies showing poorer clinical outcomes for Black veterans with PTSD in VA outpatient mental health treatment (

25,

26). Studies have also reported that non-White race is associated with poorer response to cognitive processing therapy for PTSD (

27). However, one study reported that Black veterans showed greater improvement from prolonged exposure therapy than other races (

28). Overall, more work is needed to elucidate and address potential racial disparities in clinical outcomes.

The VA PTSD residential treatment setting has not been adequately examined for racial disparities in clinical outcomes. One study of veterans in VA PTSD RRTPs from 2012 to 2013 reported that, compared with White veterans, Black veterans had 30% lower odds of clinically significant improvement (

29). Otherwise, information on race in the VA PTSD RRTP setting has largely been limited to the inclusion of race as a covariate (

30). Given that veterans treated in VA PTSD RRTPs often have more severe treatment needs and a different treatment setting (

31), further examination is needed.

The goal of the current study was to characterize whether Black veterans admitted to VA PTSD RRTPs differed from White veterans in initial PTSD and depressive symptom severity and program completion. We also sought to examine the role of race on PTSD and depressive symptom change over the course of and after treatment by using a hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) approach. We hypothesized that Black and White veterans would experience reductions in PTSD and depressive symptoms; however, given prior research, we hypothesized that symptom reduction would be less for Black veterans.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants included veterans who initiated VA PTSD residential treatment during fiscal year 2017 (i.e., October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2017). As part of the Northeast Program Evaluation Center’s (NEPEC) program evaluation of VA PTSD treatment, veterans completed self-report measures at admission and discharge. Approximately 4 months after discharge, all veterans received voluntary self-report measures via mail. The current study included data from 44 RRTPs. Average length of stay was 51 days (range 3–322 days). NEPEC does not collect data for veterans with admissions lasting less than 3 days. VA PTSD RRTPs vary in length and programming. General admission criteria included not currently meeting criteria for an acute psychiatric or medical admission, previous participation in a less restrictive treatment alternative (if available), needing an intensive level of care, not being at significant acute risk of harm to self or others, and being capable of basic self-care. Veterans who completed an intake form at admission and who self-identified their race as White or Black (N=2,870) were included in the present analyses. This study was approved by the VA Connecticut Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Veterans provided race and other demographic information on the admission form, including age, sex, ethnicity (Hispanic vs. not), and years of education. The race variable options were not mutually exclusive. All veterans who identified as Black (including multiracial) were included in the Black category, whereas the White category did not include multiracial identities. Other race categories (American Indian/Alaskan, Asian, Pacific Islander, “other,” and “prefer not to answer”) were excluded from the analyses because of small sample sizes precluding modeling (N=282, 6%, with even smaller cell sizes in each category).

Veterans indicated whether they had experienced military sexual trauma (MST) by answering the question, “Which type of traumatic incident (include both military and nonmilitary) have you suffered within your lifetime? (Check all that apply.)” Combat experience was assessed with the question, “Did you ever receive friendly or hostile incoming fire from small arms, artillery, rockets, mortars, or bombs?” This approach has been used in prior evaluations (

32).

PTSD symptoms at admission, discharge, and follow-up were assessed by using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (

33). The PCL-5 contains 20 items corresponding with the

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Possible scores range from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms. The PCL-5 has established psychometric properties (

34) and is widely used to monitor PTSD symptoms in response to treatment (

35).

Depressive symptoms at admission, discharge, and follow-up were assessed by using the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) (

36), which contains nine items corresponding with

DSM-IV-TR (

37) diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Possible scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 has sound psychometric properties and is widely used as a brief diagnostic and severity measure (

38).

Finally, veteran records were matched to the electronic medical record to obtain length of stay and the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) (or geographic region in the United States based on Veterans Health Administration designation) where the PTSD RRTP took place.

Analytic Plan

Bivariate analyses (i.e., Pearson's chi-square for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables) were conducted to determine significant differences in demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, education), experience of military-related trauma (i.e., MST, combat), rates of program completion, VISN of the PTSD RRTP, and length of RRTP stay. Factors determined to be significantly different by race were included in models as covariates.

HLM was then conducted by using SPSS, version 26.0. This approach was chosen on the basis of its ability to handle missing longitudinal data and to more accurately model variance than a repeated-measures analysis of variance (

39,

40). In the two models (i.e., one for PTSD symptoms and the other for depressive symptoms), lower-level, or level-1, data comprised repeated symptom measure (PCL-5 and PHQ-9, respectively) scores collected at admission, discharge, and follow-up. Each model was implemented at discharge to identify posttreatment symptom differences by race. On the basis of visual analysis of the growth curve a segmented growth was identified with linear change from admission to discharge and discharge to 4-month follow-up modeled (

41).

Level-1 data were then nested within upper-level, or level-2 fixed-effect, units (i.e., White, 0; Black, 1). Because of large sample size, a maximum likelihood approach was used, with a conservative threshold for statistical significance (α=0.001). Model fit was assessed by using deviance and a chi-square difference test between models. An autoregressive structure was used (

41,

42).

Results

Demographic variables, military trauma, program completion, and PCL-5 and PHQ-9 scores at admission can be found in

Table 1. Overall, age, ethnicity, education, exposure to combat, exposure to MST, and VISN of PTSD RRTP were all found to significantly differ between White and Black veterans (p<0.001). As such, these variables were included in the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 models as level-1 fixed effects. Additionally, length of stay differed between groups at a standard level of significance (p<0.05). On the basis of statistical consultation and inclusion in prior studies examining PTSD RRTP effectiveness (

29), we included length of stay as a level-1 fixed effect as well as a level-2 fixed effect nested into repeated symptom measurement.

Across models, PCL-5 scores were available for 1,848 veterans at discharge and 1,071 at follow-up. PHQ-9 scores were available for 1,699 veterans at discharge and 1,068 at follow-up. Missing data did not differ statistically significantly on the basis of race.

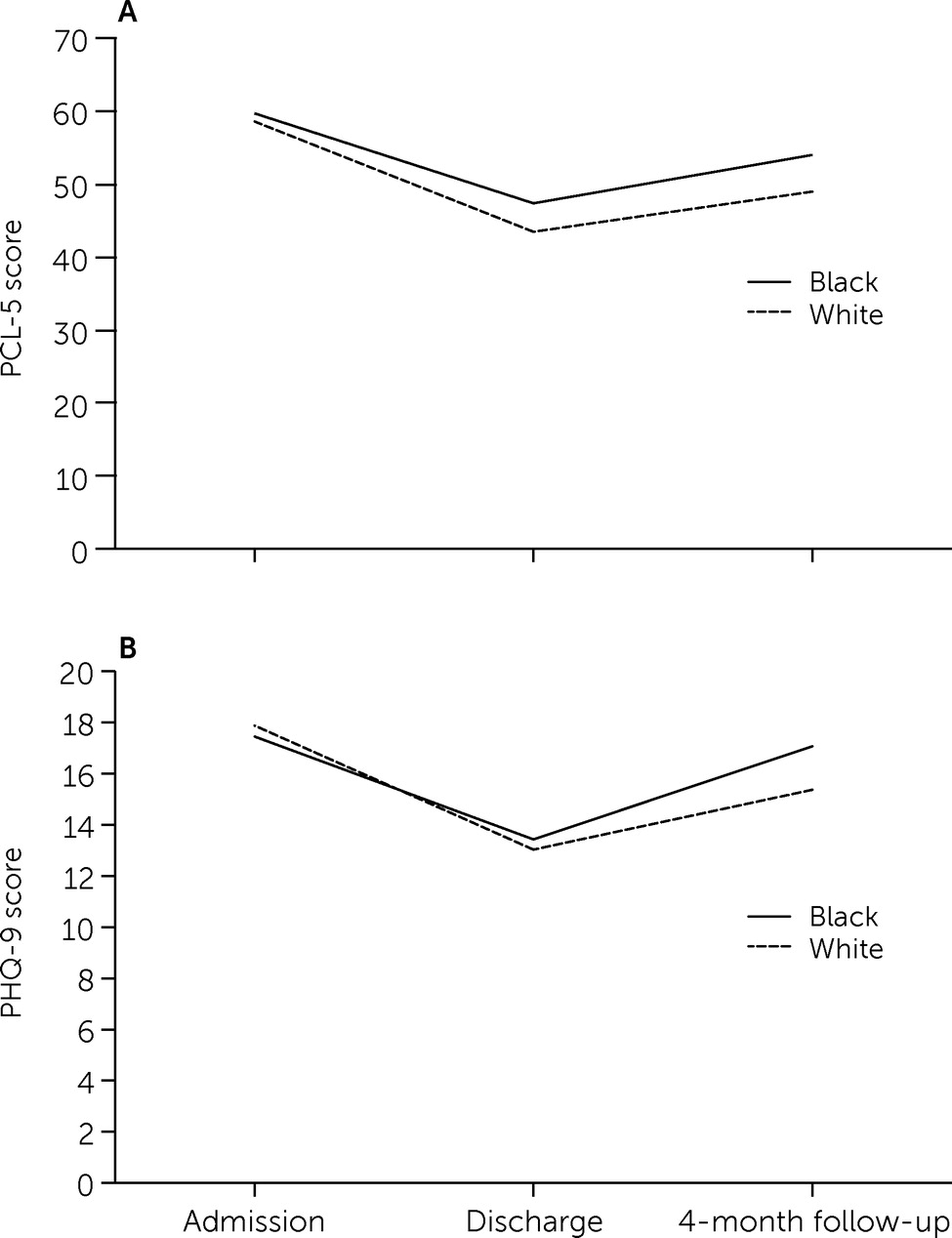

Figure 1 presents change in PTSD and depressive symptoms across the three timepoints.

PTSD Symptoms Model

Results indicated a significant decrease in PTSD symptoms over the course of treatment (β=–14.26, t=–30.14, df=2,994, p<0.001), followed by a significant recurrence of PTSD symptoms over follow-up (β=5.90, t=9.40, df=2,494, p<0.001). When race was added as a level-2 fixed-effect variable, a significant association was found during treatment such that Black veterans experienced an attenuated response over the course of the PTSD RRTP (β=3.31, t=3.93, df=2,765, p<0.001). Moreover, the main effect of race at intercept was also significant (β=5.24, t=6.40, df=4,516, p<0.001), indicating that Black veterans had significantly greater PCL-5 scores at discharge. A main effect of race during follow-up was not detected, suggesting similar slopes of PTSD symptom recurrence among Black and White veterans.

Table 2 provides the complete model.

Depressive Symptoms Model

Similarly, depressive symptoms decreased over the course of treatment (β=–4.57, t=–32.85, df=3,038, p<0.001), and veterans experienced a significant recurrence from discharge to 4-month follow-up (β=2.71, t=14.91, df=3,528, p<0.001). Differing from the PCL-5 model, when race was included as a level-2 fixed effect, in this model race only trended toward significance, on the basis of the conservative threshold, as it related to change from admission to discharge. However, a main effect for race was determined during follow-up such that Black veterans experienced significantly more recurrence in depression symptoms relative to White veterans (β=1.70, t=3.99, df=3,034, p<0.001). Additionally, the main effect of race at intercept trended toward significance.

Table 3 shows the complete model.

Discussion

Building upon prior examinations (

29), this is the first study to examine differences between Black and White veterans on longitudinal residential outcomes of PTSD and depressive symptoms during and after a VA PTSD RRTP. In general, Black and White veterans experienced significant symptom reduction during RRTP participation. However, consistent with our hypotheses, Black veterans experienced attenuated PTSD symptom reduction during treatment as well as greater depressive symptom recurrence from discharge to 4-month follow-up. These results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating poorer clinical outcomes associated with both outpatient (

24–

26) and residential (

29) treatment for Black, relative to White, veterans with PTSD. Consistent with prior literature, we also found that Black veterans reported greater PTSD symptoms at admission (

9–

11).

Our study did not allow for determination of the causes of these disparities; however, recent literature highlights the need to improve mental health care for Black veterans with PTSD. Spoont et al. (

24) reported poorer clinical outcomes for Black veterans regardless of whether they initiated treatment, and furthermore, that racial disparities in PTSD outcomes were greater among treatment initiators, indicating that treatment selectively improved outcomes for White veterans. Similarly, the current study showed disparities in symptom outcomes, but no significant differences in rates of program completion for Black veterans compared with White veterans. Thus, components of treatment that may be contributing to racial disparities in outcomes should be examined.

One such component is the working alliance between veteran and provider, which has been documented as being less strong between Black veterans and their providers (

43). This disparity has been attributed to lack of provider cultural competence and empathy and veteran experiences of racial bias. Spoont et al. (

16) reported that for treatment retention for Black veterans with PTSD, patient-rated satisfaction with providers was more important than beliefs about treatment. Black veterans in VA mental health care have reported experiences of being judged, feared, and/or stereotyped in clinical encounters (

44,

45). Black veterans voiced preference for Black therapists and cited past experiences of cultural insensitivity and racial bias from White therapists (

46).

In addition, Black veterans in VA mental health care reported a lack of minority representation, including in the characteristics of the physical space and lack of staff diversity, in particular in positions of power (

44). Minority identities, including Black identities, continue to be dramatically underrepresented among psychologists (

47). Given this context, it is not surprising that some Black veterans may hesitate to engage in care. Some studies have reported that, compared with White veterans, Black veterans are more likely to delay initiation of PTSD treatment (

48), have less confidence in managing their mental health care (

43), are less willing to speak to psychiatrists or psychologists about mental health (

49), and may be more likely to discontinue treatment prematurely (

50). It should be noted that many participants in the above studies reported positive experiences with VA mental health treatment. However, given these disparities in clinical outcomes and experiences of PTSD treatment, a continued focus on providing care that is welcoming, effective, and satisfactory to Black veterans is warranted. Furthermore, as noted above, financial factors, such as insurance coverage and affordability of treatment that disproportionately affect Black Americans are not a direct factor in the VA, yet evidence for mental health disparities persists. Therefore, the VA presents a unique opportunity to both understand and address other barriers to equitable mental health care for Black veterans.

Finally, poorer clinical outcomes for Black veterans with PTSD in our study and the literature more broadly may be due to elevated levels of stress. Members of nondominant racial groups are exposed to a greater number of stressors (including race-based discrimination) throughout life, which are directly linked to health disparities, including PTSD (

4,

51). Black veterans have reported greater perceived threat and family stressors during deployment (

52), higher rates of MST (as found in the current study) (

53), higher postdeployment life stress (veterans who recently ended active duty military service) (

7), race-based discrimination (

45), and lower education levels and income (

54). Thus, PTSD treatment for Black veterans may be enhanced by assessing for and directly addressing race-based stress when relevant. Such an approach is consistent with an intersectionality model, which considers how factors such as discrimination and privilege contribute to mental health (

55).

These results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Although we controlled for ethnicity in analyses, we did not have adequate sample sizes to include racial-ethnic categories outside of Black and White. (Note that members of other categories were included in our analyses if they also identified as Black.) In addition, although HLM is more equipped to handle missing data than other analytic approaches (

39,

40), missing data may limit generalizability of findings to all veterans who participate in PTSD RRTPs.

Additionally, we were unable to examine characteristics of individual RRTP sites, such as the percentage of Black veterans enrolled and the percentage of Black therapists and staff members. We also did not have access to information regarding specific treatments obtained by veterans while in a PTSD RRTP (e.g., cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure therapy) or mental health treatment engagement between discharge and follow-up. Therefore, additional research examining the role of program-based differences and how they may affect therapeutic response related to race remains an important future direction.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that among a national sample of veterans who completed a VA PTSD RRTP in fiscal year 2017, veterans generally benefited from treatment. Nonetheless, Black veterans experienced decreased therapeutic response during and after treatment relative to White veterans. Future research should further examine mechanisms for addressing racial disparities in clinical outcomes for VA treatment for PTSD.