In recent years, increased attention has been paid to the impact of social determinants of health (SDoHs)—the conditions in which people are born, grow, and live that affect a wide range of health outcomes and risks (

1). SDoHs include five key areas: economic stability, education access and quality, social and community context, health care access and quality, and neighborhood and built environment (

1). By affecting opportunities and resources available to individuals, SDoHs shape health and health behaviors across the life span and underlie many health inequities, such as lower life expectancies in structurally disadvantaged populations (

2,

3). The SDoH framework suggests that health disparities are rooted in social and environmental factors that cannot be adequately addressed with individual-level interventions. Despite the focus on SDoHs in other areas of research, less attention has been paid to the impact of SDoHs on the need for and access to treatment for mental disorders, especially among children (

2). As a result, mental health care providers and researchers have been called on to focus attention on addressing SDoHs as a means of improving mental health for all (

4).

There is evidence that children’s mental health is sensitive to SDoHs, with most evidence examining the effects of economic instability (

5) and adverse childhood events (

6) on children’s mental health. Various studies have shown that race and ethnicity are robust predictors of access to treatment for mental disorders, with non-White youths often having less access to mental health care than their White counterparts (

7). Although race and ethnicity themselves are not SDoHs, racism and discrimination experienced by people of color shape all the conditions in which they born, grow, and live. As such, race is considered by many to be a proxy for social and community context. Some authors, such as Paradies et al. (

8), have called for racism to be explicitly named as an SDoH. Economic stability has also been linked to treatment access, with higher income being associated with a greater likelihood of children visiting a mental health care provider (

9). However, these findings often isolate singular SDoHs in analyses or discuss them as individual-level factors, rarely acknowledging the environmental or social influences on these factors.

In this study, we examined how SDoHs are associated with both need and access to mental health treatment within a nationally representative sample of U.S. children. We address gaps in the existing literature by taking an SDoH-informed approach and examining their impact on both need and access.

Methods

We utilized data from the 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health, a nationally representative, parent-proxy survey of U.S. children. A total of 29,433 surveys were completed, for a weighted response rate of 42%. Parents indicated that their child needed treatment by answering the following question: “Does this child have any kind of emotional, developmental, or behavioral problem for which he or she needs treatment or counseling?” Parents indicated whether their child received treatment by answering the following question: “During the past 12 months, has [your] child received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional?” Parents could select “yes,” “no, but this child needed to see a mental health professional,” or “no, this child did not need to see a mental health professional.” We excluded all responses that indicated that children did not need to see a mental health professional. Our analyses were determined to be exempt from institutional review board review.

We examined eight covariates across five social determinants: economic stability, parental employment, and food security (associated with economic stability); parental education (associated with education); race and ethnicity (as proxies for discrimination and associated with social and community context); insurance coverage (associated with health and health care); and urbanicity and perceived neighborhood safety (associated with neighborhood and built environment). Parents self-reported whether they were employed 50 out of the past 52 weeks, their highest level of education (“less than high school,” “high school,” or “more than high school”), their child’s race-ethnicity, whether their child was covered by insurance, and whether they lived in a metropolitan area. Parents also responded to 4-point Likert-type questions to indicate their difficulty covering “the basics, like food or housing, on [their] family’s income” (responses ranged from “never” to “very often”); their food security (responses ranged from “we could always afford to eat good nutritious meals” to “often we could not afford enough to eat”); and perceptions that “[their] child is safe in [their] neighborhood” (responses ranged from “definitely agree” to “definitely disagree”).

We modeled associations between treatment need and access and covariates with an individual-level, multivariate logistic regression in R. Race and ethnicity were considered separately, so that each race category could include children with and without Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. (Spanish origin denotes a cultural background in a Spanish-speaking country.) Likewise, children of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin may be of any race. To better illustrate the impact of each covariate, we simulated and plotted first differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the probability of receiving treatment for significant covariates. Each simulation held all other covariates at their mean levels to highlight the change associated with just the presented change in the reference group and covariate (e.g., a difference between White and Black children receiving treatment with equivalent responses on all other covariates).

Results

Most children in the sample were White (79%, N=23,153), and most spoke English “very well” (76%, N=22,431). Full demographic characteristics for the 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health are reported elsewhere (

10). In total, 3,425 children (12%) were reported to have an emotional, developmental, or behavioral problem for which they needed treatment or counseling. Additionally, 605 children (18% of those who indicated need for treatment) were reported to not have received needed treatment for mental disorders in the past year.

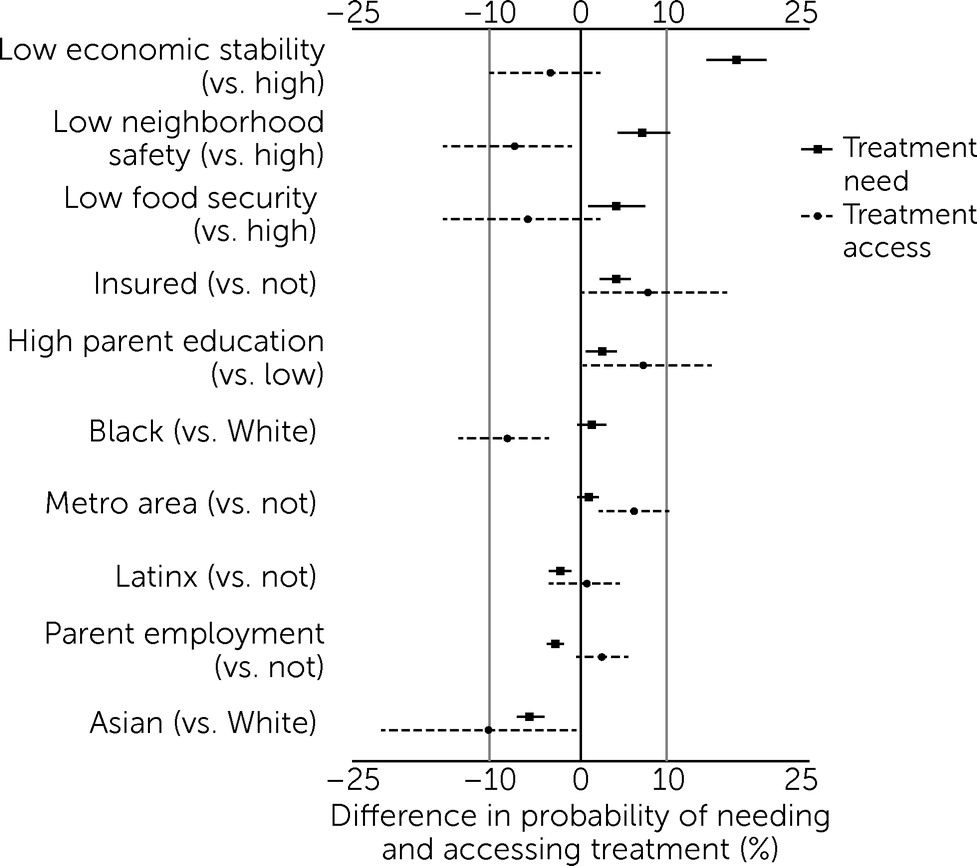

Differences in the probability of needing and accessing treatment for significant covariates are presented in

Figure 1. Greater economic instability (odds ratio [OR]=1.53, 95% CI=1.45–1.61), higher levels of parental education (OR=1.15, 95% CI=1.06–1.26), greater food insecurity (OR=1.20, 95% CI=1.12–1.29), lower perceptions of neighborhood safety (OR=1.22, 95% CI=1.15–1.29), and current insurance coverage (OR=1.70, 95% CI=1.38–2.13) were all associated with greater need for treatment (p<0.05). Asian children (OR=0.49, 95% CI=0.39–0.62) and children of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (OR=0.85, 95% CI=0.76–0.96) were less likely to report having any kind of disorder for which they would need treatment, compared with White or non-Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish-origin children (p<0.05).

Lower levels of parental education (OR=0.75, 95% CI=0.60–0.94), residence outside of a metropolitan statistical area (OR=0.62, 95% CI=1.20–2.10), lack of current insurance coverage (OR=0.59, 95% CI=0.36–0.98), and lower perceptions of neighborhood safety (OR=0.84, 95% CI=0.71–0.98) were all associated with lower likelihood of accessing treatment (p<0.05). Asian (OR=0.49, 95% CI=0.28–0.98) and Black (OR=0.56, 95% CI=0.41–0.78) children were also less likely to access treatment than White children (p<0.05).

Discussion

The SDoH framework aims to highlight how social and environmental factors are implicated in health inequities. It suggests that systems and policies shape the social conditions in which people are born and living (

1) and that, therefore, interventions are needed to modify these systems and policies in order to improve health equity. By situating our analysis within this framework, we aimed to highlight the need for greater attention to, and intervention on, social factors to improve children’s mental health.

Several covariates were associated with greater need for treatment and lower likelihood of accessing it, including perceived neighborhood safety, race, and ethnicity. The mechanisms and conditions through which these covariates affect children’s mental health are varied and likely associated with one another. These conditions may affect parental mental health, interactions with parents, and opportunities for recreation and exercise. These factors can, in turn, affect children’s need for treatment of mental disorders and better access to it. Other factors had heterogeneous associations with need and access. Higher parent education was associated with both higher need and greater access. This increase in both need and access may reflect the fact that children of more highly educated parents may have a greater likelihood of being diagnosed as having a mental disorder or that their parents have a heightened awareness of mental health conditions while also having the resources to access supports.

Notably, race (and, by proxy, racism) was among the strongest predictors of treatment access in our sample. This finding is consistent with those of other studies showing that race and ethnicity are robust predictors of access to treatment for mental disorders (

7). Experiences of racism and discrimination may affect children’s mental health directly (

11). It may also shape their experiences in other systems that are closely linked to mental health, such as the education system, where there is evidence of disparities in outcomes and discipline practices among different racial and ethnic groups (

12). The fields of clinical psychology and psychiatry themselves are deeply rooted in racism (

13). Black mental health professionals have called on White colleagues to dismantle structural racism within the field (

14). We echo these calls and call for greater action and accountability from White mental health professionals in addressing structural racism within their research and clinical work.

By not highlighting the SDoHs that are linked to mental health disparities, researchers and clinicians may obscure the true level at which intervention is needed. In the context of service provision, mental health care providers should make efforts to address SDoHs by integrating social and mental health care (

15), such as by connecting clients to material supports such as local food banks or discussing experiences of discrimination. However, given the very nature of SDoHs as socially and policy-embedded structures, fully addressing them requires advocating for structural reform. Integrating social and mental health care is only a downstream solution. We call for greater involvement of children’s mental health professionals in advocating for research-informed policies that can address the root causes of inequities and improve SDoHs for all children.

These findings are not without limitations. Notably, our results were limited by their self-report nature and lack of true diagnostic information. Self-reported need and access to treatment may have been biased, and some respondents may have mischaracterized their children as having (or not having) a mental condition that warranted treatment or counseling. Some parents may have not known whether their child had a mental condition that warranted treatment, because they were unable to access routine primary care services. Others may have not reported their child’s condition because of stigma or medical mistrust. The size of our sample also precluded definite conclusions for other racial groups and disaggregated populations within each racial group, which again highlights an inequity not only in mental health services but also in the conduct of “nationally representative” surveys. Additionally, analyses were limited by our inability to conduct multilevel models that aggregate and test the impact of neighborhood-level covariates. Further research is also needed that examines how multiple SDoHs may work in concert to affect mental health. This research should seek to center the narratives and perspectives of individuals who are affected and not just reduce intersections among SDoHs to interactions in statistical models.

Conclusions

Our results reveal the significant effects of several SDoHs on children’s mental health in the United States. Although mental health care providers and researchers have long acknowledged the effects of social factors on mental health, little research has taken an explicit SDoH approach and implicated the structural inequities that underlie individual-level risk factors. By addressing SDoHs, in both patient care and policy-oriented work, mental health care providers and researchers may help improve children’s mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Natalie Chisam for her support and review of drafts of this report.