Researchers who have studied the efficacy of psychotherapy have consistently shown that the nature of the therapeutic alliance predicts clients’ treatment outcomes, accounting for approximately 8% of the variance in outcomes (

1–

3). Research on a related concept, the working alliance in mental health case management, is less extensive. Some case management research has shown that a stronger client–case manager working alliance is associated with decreased levels of mental health problems, higher functioning, and higher satisfaction with care (

4–

7). Effects of this alliance-outcome relationship are similar to those found in psychotherapy studies, with effect sizes (assessed as Pearson r correlation) ranging from 0.19 to 0.32 (

3).

The many types of mental health case management, and variations in their local implementation, have posed challenges for interpreting evidence on the effectiveness of case management for improving treatment outcomes (

8). Few studies describe the roles of case managers or mechanisms leading to changes in outcomes for clients (

8). Although fidelity measurement is a growing priority in establishing evidence-based practices in the community mental health field (e.g., assertive community treatment and Housing First), most case management interventions lack fidelity measures (

9).

Unlike other case management models, strengths model case management (SMCM) for people with severe mental illness has an explicit theoretical framework and structure (

5,

10). SMCM has a fidelity measure to systematically determine how closely a program follows the model’s principles and tools (

10). SMCM focuses on helping clients identify meaningful goals and leverage strengths to achieve their goals. The intervention is framed by six overarching principles, one of which is that the client–case manager relationship is primary and essential (

10).

Studies with SMCM have shown that the intervention can lead to improvements in clients’ quality of life, life satisfaction, and goal attainment compared with other forms of community supports (

10–

14). One study found that SMCM fidelity is associated with clients’ achieving higher levels of employment and education and having lower levels of hospitalization (

15). Another study reported trends toward higher hope, greater well-being, and better recovery in a high-fidelity SMCM subgroup compared with treatment as usual (

13). Three studies have examined the client–case manager working alliance in SMCM (

13,

16,

17). Two of these studies were qualitative, reporting that a close working alliance was associated with receipt of SMCM and increased personal change (

16,

17). In the quantitative study (

13), very high SMCM fidelity trended toward a positive association with the strength of the working alliance. We are not aware of any quantitative studies that have examined the associations among SMCM, the working alliance, and client outcomes. More SMCM research is therefore needed, examining both the fidelity-outcome relationship and the role of the working alliance.

The purpose of this study was to examine how the client–case manager working alliance mediates fidelity to SMCM (at the team level) and clients’ outcomes. We defined a strong working alliance as one in which clients and case managers formed a close bond and agreed on intervention goals and on the tasks to achieve these goals (

18). This definition fit with SMCM theory and the working alliance measure that was available to us (

10). We hypothesized that a higher level of SMCM fidelity would predict a stronger working alliance. In turn, a stronger working alliance would predict greater improvements in clients’ outcomes during their participation in the study.

Methods

Participants

In total, 311 people participated in this study. Participants had to have been enrolled in SMCM ≤6 weeks before the baseline interview and to meet eligibility criteria for SMCM at the participating organization. All of the participating organizations required that a participant have a mental illness severe enough to interfere with one or more daily activities. Fourteen case management teams in seven mental health organizations in the Canadian provinces of Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Quebec participated in the study. Participating case management teams agreed to adopt SMCM. The teams received initial training on this approach, as well as follow-up mentoring from SMCM experts at the School of Social Welfare, University of Kansas. Although one of the organizations had already been trained in SMCM, none of the teams began the study period with high SMCM fidelity.

Measures

Program fidelity.

The SMCM fidelity scale (see an

online supplement to this article) determines how closely case management teams (not individual case managers) follow SMCM. The measure assesses 31 items grouped within nine domains: caseload size, community contact, individual supervision, group supervision, use of a strengths assessment, use of the personal recovery plan, integration of the strengths assessment and treatment plan, resources available outside of the formal mental health system, and hope-inducing practice (

10). The integration of the strengths assessment and treatment plan domain was excluded from this study because each province used different tools for planning treatment; hence, item scores were not comparable across provinces. The total fidelity score was the sum of the mean score of items per domain. Total scores could range from 8 to 40; a total score of ≥32 indicated high fidelity (

10).

Ten clinical experts (supervisors of participating case management teams, a provincial trainer, and a consultant) were trained by SMCM consultants to conduct fidelity assessments (of agencies that were not their own). Each 2-day fidelity assessment was conducted by two assessors and consisted of reviews of randomly selected case records (approximately 10), one observation of a team meeting, at least one interview with a supervisor, and interviews with approximately five clients and five case managers. After the 2 days, the two assessors reviewed their feedback together to create item ratings.

Client–case manager working alliance.

The 24-item Recovery-Promoting Relationships Scale (RPRS) describes the relationship between clients and their mental health providers (

19). Clients respond to statements about their case manager on a 4-point agree-disagree Likert scale; statements include “My provider helps me feel hopeful about the future” and “My provider helps me learn from challenging experiences.” Although the RPRS is a measure of recovery-promoting relationships, it can be viewed as operationalizing the case manager’s contribution to the working alliance from the client’s point of view. Total RPRS scores have been shown to highly correlate with the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) (r=0.79) (

19). Total RPRS scores range from 0 to 100.

Outcome measures.

Quality of life was measured with Lehman’s standardized brief version of the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI-20) (

20) and the Patient-Generated Index (PGI) (

21,

22), a personalized, idiographic quality-of-life measure. Hope was assessed with the Trait Hope Scale (THS) (

23), and the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (

24) was used to assess community functioning.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained individually for each participating site in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador and centrally in Quebec agencies. New service clients entered the study from October 9, 2014, to August 24, 2016, and were invited to participate in five structured interviews, conducted every 4.5 months, to complete the client measures. Participants provided informed consent before the baseline interview at 0 months. The interviewers were researchers external to the participating agencies. The baseline, 9-month, and 18-month interviews were conducted in person and included the outcome measures. The 4.5-month and 13.5-month follow-up interviews included the RPRS and were conducted by telephone unless a person requested an in-person interview. Participants were given a small honorarium for each interview ($25 for in-person interviews and $15 for the telephone interviews). Interviews were conducted in either French or English, according to the language preference of the participant.

Six fidelity assessments were conducted for most teams: at baseline and then at approximately 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, and 36 months. One team dropped out of the study early, thus ending further efforts at SMCM implementation. This team completed four fidelity assessments, and their data were included in this study.

Data Analysis

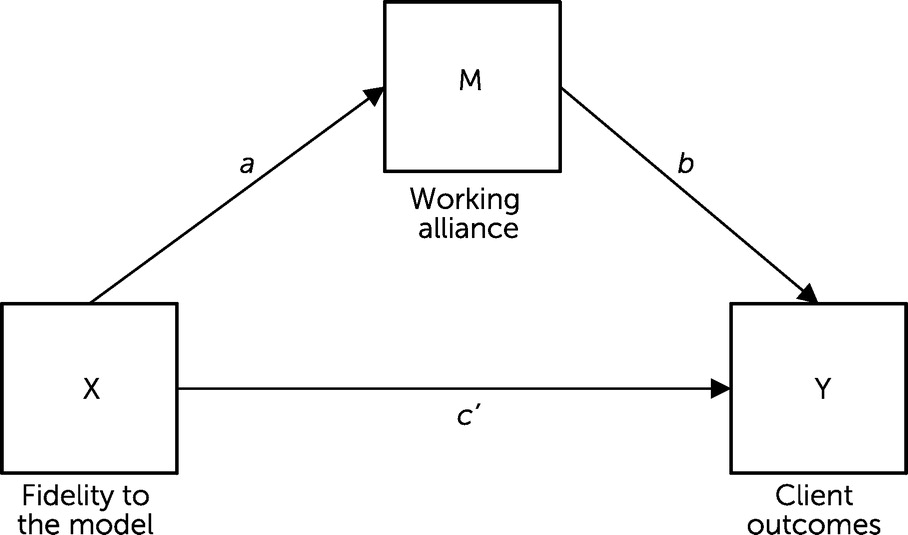

At the scale level, 11.6% of the data were missing and were replaced by using multiple imputation at the item level. Simple mediation models were tested with ordinary least-squares path analysis conducted with PROCESS 3.4.1 in IBM SPSS, version 26. See

Figure 1 for a diagram of the mediation model. The models included nine covariates: age, gender, housing status (stable or unstable), employment (unemployed or employed), education, adverse childhood experiences, site, hospitalized for ≥6 months in the past 5 years (or not), and the baseline score of the outcome measure being tested.

For the client-level analysis used in this study, a daily team fidelity score was calculated for each day of the study by using linear interpolation. The level of fidelity experienced by each client was calculated as the average level of SMCM fidelity of a client’s case management team over the previous 6 months (180 days) leading up to each client interview date; 3-month (90-day) and 9-month (270-day) average SMCM fidelity scores were also calculated for each participant interview and were used for sensitivity analyses.

The simple mediation model was tested eight times with Model 4 of PROCESS (

25). Each of the four outcome variables was tested at both 9 months and 18 months. The 4.5-month working alliance score was the mediator in the models testing the 9-month outcome variables. The 13.5-month working alliance score was the mediator in the models testing the 18-month outcomes. The average fidelity assessed for the period before the 4.5-month interview or in the 6 months preceding the 13.5-month interview was used to match the time points when the working alliance was assessed in the analyses.

Bootstrap percentile confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine the statistical significance of indirect effects on client outcomes (the effect of SMCM fidelity on client outcomes, through the mediator variable, i.e., the working alliance). We used 5,000 bootstrap samples to construct 95% CIs. In addition, effect sizes of the indirect relationship coefficients were reported by using completely standardized indirect effect size in PROCESS (

25).

Nested data.

In analyses, clients were nested within case managers in 14 case management teams. Such nonindependence in the data can lead to inflation of type I error rates (

26). Intraclass correlations coefficients (ICCs) of the study’s dependent variables ranged from 0.02 to 0.12, indicating that the nonindependence in the data was low, but some variability (ICC>0.05) was not low enough to ignore (

27). To minimize the risk for type I errors, alpha levels were adjusted from p<0.05 to p<0.01 post hoc for study analyses that included a dependent variable with an ICC>0.05 (

27) (i.e., for QOLI-20, PGI, and MCAS scores at 18 months; MCAS scores at 9 months; and the RPRS score at 13.5 months). If coefficients of effects that included these variables had p>0.01, they were considered statistically nonsignificant, and their mediating paths were also considered nonsignificant. The site ID variable was also a covariate in the analyses to control for differences in findings due to site differences.

Power analysis.

Using G*Power software, we determined that with a sample of 311 clients, the multiple regression analyses had a power of 0.99 for detecting an X-M path effect (of fidelity on the working alliance) and M-Y path effects (of the working alliance on client outcomes) (see

Figure 1) at the 0.05 level. According to Fritz and MacKinnon (

28), for mediation models a sample size of 558 is needed to obtain a power of 0.80 for an indirect effect with small standardized coefficients (β=0.14) of X-M and M-Y and 95% CIs. For an indirect effect with standardized coefficients of β=0.26 for both X-M and M-Y effects and 95% CIs, a sample size of 162 is needed to obtain a power of 0.80. Considering these power analyses, we determined that the tests of the indirect mediation effects may have been underpowered; therefore, we decided to also report the regression coefficients for each path.

Results

Table 1 describes the participant characteristics.

Table 2 provides the mean scores of the study variables and results of mean comparison tests. During the study, both the fidelity of case management teams to SMCM and client outcomes improved. At the end of the study, the teams that remained in the study were approaching, or had reached, high fidelity to SMCM (see the

online supplement).

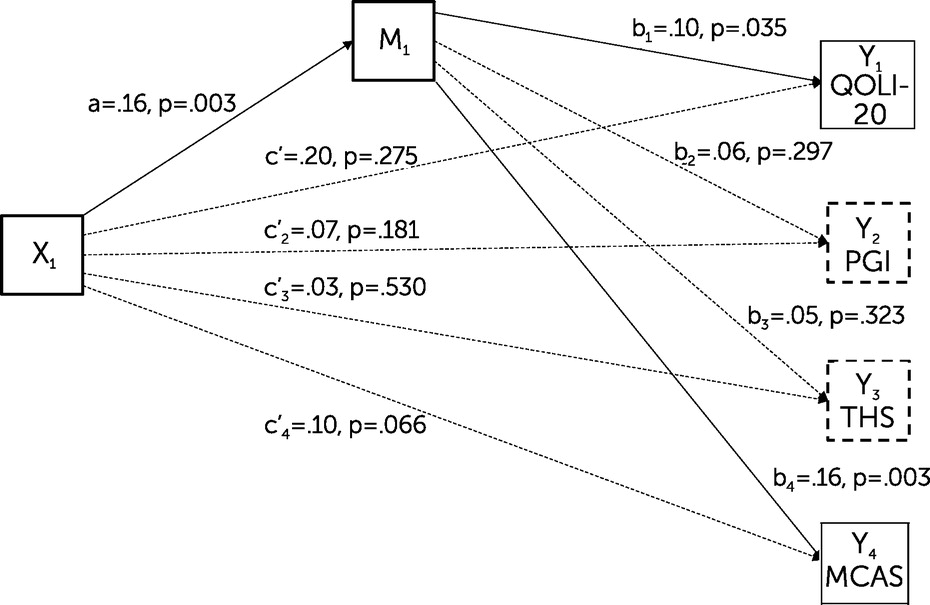

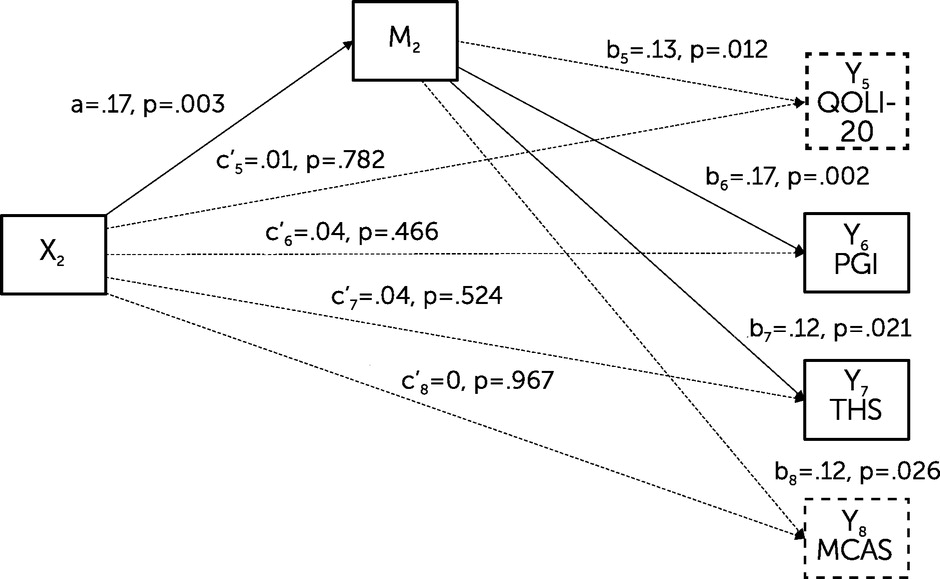

Figures 2 and

3 present the results of the mediation analyses. Higher fidelity to SMCM predicted a stronger working alliance at both 4.5 months (unstandardized coefficient for the effect of the predictor variable on the mediator variable [a]=0.65, 95% CI=0.22–1.09, p=0.003) and 13.5 months (a=0.63, 95% CI=0.22–1.05, p=0.003). In addition, clients who reported a stronger working alliance had higher quality of life (i.e., QOLI-20 score) at 9 months (effect of the mediator variable on the outcome variable [b]=0.10, 95% CI=0.01–0.20, p=0.035), higher patient-generated quality of life (PGI score) at 18 months (b=0.21, 95% CI=0.07–0.34, p=0.002), higher community functioning (MCAS score) at 9 months (b=0.05, 95% CI=0.02–0.09, p=0.003), and higher hope (THS score) at 18 months (b=0.07, 95% CI=0.01–0.12, p=0.021). The effect of the working alliance on the quality of life variable (QOLI-20) at 18 months approached significance (b=0.16, 95% CI=0.03–0.26, p=0.012).

Regarding the paths from SMCM fidelity to client outcomes through the working alliance (X to M to Y), the indirect path coefficient (ab) was >0 (indicating a significant mediating path) for the QOLI-20 outcome at 9 months (ab=0.07, 95% CI=0.00–0.16). The indirect path coefficient was >0 for the PGI outcome at 18 months (ab=0.12, 95% CI=0.02–0.27), the THS score at 18 months (ab=0.04, 95% CI=0.00–0.10), and the MCAS score at 9 months (ab=0.04, 95% CI=0.01–0.08). The completely standardized indirect effect sizes for the significant mediation models ranged from 0.017 to 0.027, with 95% CIs >0. Two cases that differed by one standard deviation of X (SMCM fidelity) resulted in a small change of 0.017–0.027 SDs in Y (the outcome variable) through the indirect path. All of the simple mediation models provided no evidence that SMCM fidelity influenced client outcome scores independently of the working alliance. When we ran sensitivity analyses with the 3-month or 9-month fidelity scores, the fidelity and working alliance effects on outcomes and the indirect path results remained the same.

As a follow-up exploratory analysis to examine a potential reciprocal relationship between the working alliance and client outcomes, the outcome variables at 9 months were positively associated with the working alliance at 13.5 months. Four hierarchical multiple regressions were performed, first entering the nine covariates in step one, then entering a 9-month variable in step two (QOLI-20, PGI, THS, or MCAS score). The dependent variable was the working alliance at 13.5 months. When the 9-month outcome variable was entered into the model, the change in amount of variance in client outcomes explained ranged from 1% to 5%. The change was statistically significant for the QOLI-20 score (R2=0.11, F=10.67, df=1 and 300, p=0.001), and MCAS score (R2=0.11, F=17.12, df=1 and 300, p<0.001).

Discussion

Our findings support the study hypotheses. Higher fidelity to SMCM predicted a stronger client–case manager working alliance. In turn, a stronger working alliance predicted greater improvements in clients’ quality of life (i.e., significantly increased the QOLI-20 score at 9 months and the PGI score at 18 months), hope (at 18 months), and functioning (at 9 months). Fidelity to SMCM did not directly predict improvements in client outcomes during their participation in the study.

These findings align with predictions from strengths model theory, which describes the working alliance as a key ingredient to producing positive outcomes (

10). SMCM is defined by structures and processes that researchers who study working alliances hypothesize are playing a role in the formation of strong working alliances: agreement on goals, smaller caseloads, viewing the healthy side of a person, and a structured intervention (

1,

5,

29–

31). Aligning with Tsoi et al.’s findings (

13), we found that fidelity to SMCM predicted stronger client–case manager working alliances.

Our findings also build on a body of literature showing that the strength of the case management working alliance predicts improvements in recovery outcomes for people with severe mental illness, suggesting the importance of measuring the strength of the client–case manager working alliance in outcome studies (

5,

13,

32,

33). Case management researchers have reported positive relationships between the working alliance and a range of client outcomes, including housing stability, life satisfaction, functioning, and social support (

7).

The differences in significance of the mediation paths across time points could be due to several factors. The PGI scores at 9 months did not significantly differ from those at baseline (see

Table 2). Hence, it is realistic to expect that the PGI mediation model could reach significance only at 18 months. Additionally, Browne et al. (

34) found that clinician contributions to the working alliance were most closely associated with subjective recovery outcomes, whereas client contributions to the alliance were most closely associated with functional and symptomatic outcomes. In our study, the functioning outcome (i.e., MCAS score) findings were less consistent, possibly because of our use of the RPRS, which measures the case manager’s contribution to the alliance.

The finding that client outcomes at 9 months were associated with the strength of the working alliance at 13.5 months suggests a reciprocal relationship between strength of the alliance and client outcomes. In a meta-analysis of psychotherapy literature (

35), the alliance and symptoms had a reciprocal relationship throughout therapy, with a stronger alliance leading to lower symptom intensity, which in turn contributed to a stronger alliance. Additional study analyses have been conducted and are published separately (

36). Of note, we applied linear regression to examine the association between SMCM and clients’ outcomes and also found no direct fidelity-outcome association.

We note some limitations of this study. The power analyses for the mediation analyses suggested that the sample size in our study may have been too small (

28). As such, some nonsignificant findings might have been statistically significant with a larger sample. We used the RPRS to operationalize the working alliance because of RPRS’s availability and the very high correlation of RPRS scores with WAI scores. Further research could use the WAI to replicate our findings.

Assigning team-level fidelity scores to individual clients’ interviews failed to account for differences in fidelity among case managers, possibly reducing the size of the effects of fidelity and working alliance on client outcomes in this study. In research on community mental health, single fidelity scores are usually assigned to teams (

9). Measuring fidelity at the level of case manager would have yielded a more precise assessment of fidelity but would have been more resource intensive.

The nesting of data was accounted for by adjusting alpha levels and including a site variable as a covariate, but further studies could control for case manager and team effects on the alliance-outcome relationship, for example, by using multilevel modeling. The different levels of SMCM fidelity allowed for testing the mediation model in this observational study. Further research could include comparisons among randomized groups. Additional research could also examine the associations among SMCM fidelity domains, working alliance, and client outcomes to examine SMCM elements more in depth (

14).

Conclusions

The findings of this study strengthen the evidence of SMCM’s effectiveness, highlighting the centrality of one of its core principles, namely, that the client–case manager relationship is a critical ingredient for positive changes in client outcomes. The findings also add to a smaller research base on the working alliance in case management compared with the extensive work that has been done on the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Finally, the results of this study support the ongoing monitoring of implementation fidelity to achieve high-fidelity SMCM, which can contribute to strong working alliances and thereby to improvements in the quality of life of people with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the people who participated in this study. The authors acknowledge Christian Méthot for project coordination and Veronika Huta and Dwayne Schindler for statistical expertise. They thank John Sylvestre, Giorgio Tasca, and Benjamin Henwood for expert guidance; François Neveu, Danielle Hogan, John Dinn, and Jean Keough for their fidelity assessment support; and Ally Mabry and Matthew Bomhoff for training assistance.