The use of seclusion and mechanical restraints (S-R) in psychiatric hospitals is traumatizing and retraumatizing to both staff and individuals in treatment. S-R is also associated with an unacceptable risk for lethality. S-R practices remain widespread despite the availability of effective, noncoercive, evidence-based approaches to prevent conflict and violence.

Psychiatric hospitals should be places of sanctuary for individuals seeking treatment and safe workplaces for staff—all persons should be safe from physical trauma, sexual trauma, psychological trauma (e.g., coercion and threats), and neglect. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and The Joint Commission (TJC) have not updated their S-R regulations with best practices since 2005, despite compelling data on the effectiveness of trauma-informed approaches—such as the six core strategies to prevent conflict, violence, and the use of seclusion and restraints (6CS) and the sanctuary model—in reducing violence, injury, emergency medication use, and S-R use in psychiatric hospitals. In this article, the authors first review the history of the call for the cessation of the use of S-R and the history of the development of trauma-informed practices. The authors then describe the successful and sustained (for nearly a decade) cessation of S-R use by the Pennsylvania State Hospital System via its continuous adherence to 6CS and contrast that outcome with the significant fall in S-R use at a public hospital that implemented 6CS while under U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) monitoring and the resumption of S-R use when the hospital discontinued 6CS practices after DOJ monitoring ended. The contrast highlights the importance of external regulatory mandates to sustain adherence to practices that lead to the safe cessation of S-R use. In light of those data and the cautionary tale of the reversal of gains in S-R reduction after DOJ oversight ended, the authors call for and propose updated regulatory action by CMS and TJC to mandate the reduction and eventual cessation of the use of S-R in psychiatric hospitals.

The History of the Call for the Cessation of S-R

The call for the cessation of the use of S-R started when individuals with treatment experiences in psychiatric hospitals began to speak of the traumatizing and retraumatizing effects of being placed in seclusion or mechanical restraints. In 1998, the landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study shed light on the high prevalence and serious consequences of childhood traumatic experiences (

1). The ACE study was enormously impactful, was widely replicated, and led to a national call for “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care appreciates the prevalence, impacts, and sequelae of trauma and aims to avoid retraumatizing individuals seeking treatment—that is, it is care that seeks to first, do no harm. The same year as the publication of the ACE study, a series of reports by the

Hartford Courant exposed the lethality of the use of mechanical restraints, with the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis estimating that one to three individuals die per week in mechanical restraints in the United States (

2).

Whereas the traumatizing and retraumatizing effects and the lethality (from asphyxia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, physical trauma, etc.) of mechanical restraints are well known, the traumatizing effects of seclusion are being more clearly understood as the importance of social interaction and support in wellness, resilience, and recovery is further uncovered (

3–

5). In 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama banned the solitary confinement of juveniles in federal prison because of those concerns (

6). Speaking to the traumatizing and retraumatizing effects of S-R, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) declared in 1999, “Any intervention that recreates aspects of previous traumatic experiences or that uses power to punish is harmful to the individual involved” (

7).

The Development of Trauma-Informed Practices

The development of trauma-informed practices has addressed the safety of individuals in treatment and the safety of hospital staff, who often feel as though S-R is their only recourse in the face of violence from individuals in treatment. Trauma-informed approaches such as the sanctuary model and 6CS train staff to prevent conflicts and violence and, as a result, to decrease their reliance on the use of S-R. Unlike crisis intervention models, which are reactive (implemented when a behavioral code is called or when an individual is already agitated or engaging in violence), trauma-informed approaches are proactive, primary prevention strategies aimed at stopping violence from occurring. Trauma-informed practices decrease the likelihood that individuals in treatment will be triggered; consequently, these practices can prevent self-injury, violence, and the use of S-R.

The sanctuary model, a trauma-informed approach to care, was developed in psychiatric hospital settings in the 1980s by Sandra Bloom, M.D., and has been shown to reduce violence, injury, S-R use, emergency medication use, and staff distress and turnover (

8–

11). Since then, the model has developed into an evidence-supported, evolving, whole-system organizational change process that is used across human service systems (hospitals, juvenile justice facilities, domestic violence shelters, etc.) in many organizations in the United States and abroad (

9).

Charles Curie, deputy secretary for mental health in Pennsylvania from 1996 to 2001 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) administrator from 2001 to 2006, stated in 1997 that “seclusion and restraint reflect treatment failure” (

12). That declaration challenged Pennsylvania State hospitals to extend their ongoing efforts in the 1990s to reduce their use of S-R. By 2000, the nine Pennsylvania State hospitals (including two forensic hospitals) had achieved significant reductions in the rate and duration of S-R use (with some hospitals reporting cessation of S-R), with no increase in staff injuries related to patient assault (

12).

With the increased scrutiny on S-R practices generated by the 1998

Hartford Courant series (

2) and the resultant U.S. congressional hearings, NASMHPD began receiving calls from state mental health commissioners asking for assistance in reducing the use of S-R in their public hospitals. In response, NASMHPD’s National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning developed the 6CS. With information from the

Hartford Courant series (

2), the report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office commissioned by Congress (

13), and the first two installments of the NASMHPD medical director’s series on restraints (

14–

16), the center hosted focus groups in 2001 with subject matter experts to identify what had worked to reduce S-R use in a variety of behavioral health settings across the United States, including in the Pennsylvania State hospitals under the stewardship of Charles Curie and in facilities using the sanctuary model. 6CS emerged from this service-to-science approach and was developed into a 2-day training curriculum by the end of 2001 (

17). From 2004 to 2009, SAMHSA funded a multisite research project in 43 facilities across eight states to determine the effectiveness of this model. Findings demonstrated the feasibility of implementing the model in different facility types, and participating facilities reported reductions in the use and duration of S-R (

18). On the basis of these findings, 6CS was accepted as an evidence-based practice in 2012 (

17). Since 2002, 6CS has been implemented in numerous public and private facilities in 45 U.S. states and seven countries (Australia, Canada, Finland, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom). 6CS has been shown to prevent the use of S-R without an increase in injuries to staff or individuals in treatment or an increase in the use of emergency medications (

19–

26). Other staff-related and economic benefits, such as reduced staff turnover and savings from workers’ compensation and disability claims, have also been reported (

27). The 6CS comprise the following: holding leadership accountable for organizational change, using data to inform practice, developing the workforce, using S-R prevention tools, ensuring the involvement of consumers and peer advocates, and holding rigorous debriefings after every S-R event.

The Pennsylvania State Hospital System, which was a pioneer in the efforts to reduce S-R use and has been reporting on its outcomes for more than 20 years, recently reported on the effects of its cessation of S-R use and the importance of continued adherence to 6CS to this sustained achievement. In 2022, Smith et al. (

28) reported that in Pennsylvania’s six civil hospitals and two forensic hospitals, the use of seclusion ended in 2013 and the use of mechanical restraints ended in 2015. Between 2011 and 2020 in the eight Pennsylvania hospitals, assaults, aggression, self-injurious behavior, the use of emergency medications, and the frequency and duration of physical restraint significantly declined or were unchanged (

28).

A Cautionary Tale: Implementation and Discontinuation of 6CS

Since 1980, the DOJ has investigated conditions in hundreds of facilities nationwide under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act. Conditions in many facilities have warranted further investigation and have required the implementation of consent decrees, settlement agreements, and court orders. Below is a description of the implementation and outcomes of 6CS at a 300-bed public psychiatric hospital with a 60% forensic population that entered into a settlement agreement with DOJ after it was cited for excessive use of S-R, among other problems. The cautionary tale below describes what happened when the hospital ceased practicing 6CS after DOJ monitoring ended.

Implementation of 6CS: Years 1–6

Leadership accountability for organizational change.

Hospital leadership supported an extensive, mandatory annual training requirement for all staff as well as substantial policy changes, including reduction of the maximum allowable duration of restraint use from 4 hours (TJC standard) to 1 hour and cessation of the use of prone and ambulatory restraints. Leadership also supported the creation of a voluntary group of staff members, across all departments, who were on call 24/7 to report to a unit and support other injured staff after an assault. “Rule-busting” committees were created that were unit based, included both staff and individuals in treatment, and were meant to review unit rules that tended to cause conflict (use of telephones, visitation, snack times, etc.) and devise mutually agreed-on practices that afforded all persons a sense of being heard and valued.

Use of data to inform practice.

The quality improvement department was reconfigured and focused on gathering reliable data that could be tracked. A monthly report with data on assaults and S-R use (among other measures) was released on the hospital’s public website. When national benchmarks were available, such as the NASMHPD Research Institute’s national public rate, the report listed those data side by side with the hospital’s data for comparison with national trends.

Workforce development.

At the core of 6CS is culture change, which can be achieved only with extensive and ongoing staff training and supervision. Staff training at the hospital was mandatory, extensive (3 hours with pre- and posttesting), part of new employee orientation, and required to be completed annually thereafter. The annual training was complemented by individual consultations (as needed) for particularly challenging clinical situations (e.g., individuals prone to violence, self-injurious behavior, ingestion of foreign objects). Additional training was provided to offer more trauma-specific therapies, including dialectical behavior therapy.

Use of S-R prevention tools.

A review was conducted of the physical environment of care, including the physical plant and the language used in signage, to ensure that the environment created a sense of safety and community. The hospital transitioned to a newly built facility in the middle of year 3 of the 6CS implementation. The new facility included private rooms and single-occupant shower rooms for privacy. The nursing stations in the new facility were built without plexiglass barriers, which allowed for greater interaction between staff and individuals in treatment.

Other prevention tools that were implemented before the move to the new facility included the use of comfort plans and sensory modulation items. In comfort plans, direct-care staff document each individual’s triggers (e.g., loud noises, nighttime, being disrespected, lack of control, lack of choice, certain anniversaries), early warning signs that the individual is becoming triggered (e.g., palpitations, pacing, isolation, cursing, becoming loud), and what helps that person soothe (e.g., being alone, talking with staff or peers, calling a relative or friend, listening to music, journaling). This knowledge is fundamental to preventing violence by creating safe spaces, avoiding triggers, identifying early when a trigger has been tripped, and facilitating person-specific interventions that are known to be soothing to that individual. Extensive training for direct-care staff on how to elicit and document this information from individuals in treatment was ongoing and emphasized the importance of passing newly gleaned information from shift to shift. Placing the development and maintenance of the comfort plans in the hands of direct-care staff, who spend the most time with individuals in treatment, helped to transform their role from a custodial one to a more therapeutic role.

The introduction of sensory modulation items (weighted blankets, weighted neck pillows, massagers, modeling clay, sour candy, etc.) also required extensive training. The training emphasized that these items should be selected by individuals early in their treatment on the basis of their preferences and should be kept by them during their stay in the hospital. Staff were instructed that the items should not be used as rewards, withheld as punishment, or used for the first time when an individual in treatment is already agitated. Instead, the items are meant to afford individuals some measure of soothing when they are well, such that their threshold for being triggered is higher.

Peer and advocacy roles.

Because the movement toward the cessation of S-R use was started by individuals with previous treatment experiences in psychiatric hospitals, the robust and consistent participation of individuals with lived experience (peer support staff) is critical to the implementation of 6CS. The unit-based training nearly always included a certified peer specialist in addition to NASMHPD and hospital staff. Family members of individuals in treatment, staff from the state’s protection and advocacy office (disability rights attorneys and staff), and hospital staff union representatives were also invited to participate in the training to ensure robust advocacy for both staff and individuals in treatment.

Rigorous S-R debriefing.

Rigorous debriefings were conducted after all S-R events. 6CS debriefings are structured and are not intended to be accusatory or punishing; rather, they are meant to be formative and to assess, at each debriefing, progress in the efforts to prevent violence and S-R use. As more staff were trained and as they became more skilled at reviewing the events before an S-R episode and at drawing conclusions on their own, the hospital leadership team was able to change its role from facilitating the debriefings to serving as advisors.

End of DOJ Monitoring and Discontinuation of 6CS: Middle of Year 7

DOJ monitoring of the hospital ended in the middle of year 7 after the hospital met the terms of the agreement and achieved substantial reductions in S-R use. After DOJ ceased its monitoring visits, which had occurred every 6 months, 6CS practices were phased out and ultimately ceased.

Outcomes

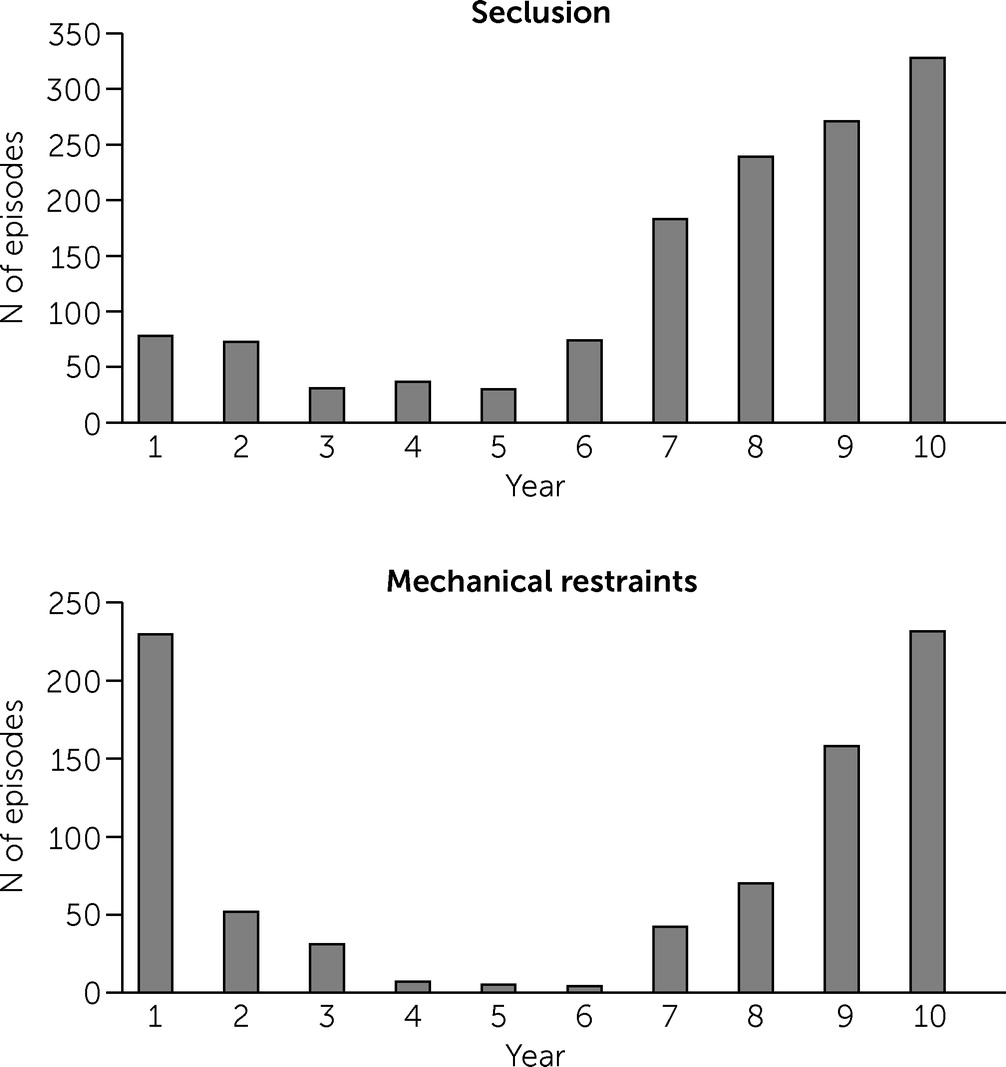

At this hospital, 6CS was implemented under DOJ monitoring from year 1 through year 6; DOJ monitoring and 6CS practices ended in the middle of year 7 (

Figure 1). The data show the effectiveness of 6CS in preventing S-R use in the challenging setting of a 300-bed public psychiatric hospital with a 60% forensic population under DOJ monitoring. Mechanical restraint episodes declined by 77% by year 2 and by a sustained 98% from years 4 through 6. In year 1 there were 230 episodes of mechanical restraint use, in year 4 there were seven, in year 5 there were five, and in year 6 there were four (

Figure 1). Seclusion episodes declined by 6% in year 2 and by 53%–62% from years 3 through 5. The initial reductions in S-R were related to immediate changes in policy and oversight, and the later dramatic, sustained reductions (3 consecutive years of single-digit mechanical restraint episodes) speak to the ongoing training–related increased skill of staff and to the fundamental culture change of the hospital.

The reversal of the gains in S-R reduction started in the middle of year 7, when 6CS practices ceased after DOJ monitoring ended. That adherence to 6CS ceased when DOJ monitoring ended speaks compellingly to the need for external, regulatory oversight to achieve sustained adherence to trauma-informed practices, which can be ensured only by CMS and TJC regulatory mandates. Although the hospital underwent other changes in the 6-year period of the implementation of 6CS, including moving into a newly built facility with private rooms and single-occupant shower rooms, the implementation of 6CS led to the reductions in S-R use, as evidenced by the significant reductions before the move into the new facility (which did not occur until the middle of year 3). Moreover, and importantly, the reversal of the gains in S-R reduction occurred entirely in the new hospital facility (with the same census and proportion of forensic admissions) after 6CS was discontinued. Because hospitals can change policies, practices, and training requirements at any time, regulatory mandates from CMS and TJC are needed to sustain fidelity to evidence-based models such as 6CS. After DOJ monitoring ended, when the hospital was no longer compelled by external mandate to show reductions in S-R use, 6CS was discontinued—6CS oversight, training, supervision, debriefings, and consistent use of comfort plans and sensory modulation items all ceased. In addition, the hospital implemented other practices ostensibly meant to reduce violence but that have the opposite effect: reerecting nursing station plexiglass barriers and deploying uniformed security guards. Nursing station barriers and uniformed security guards are often triggering for individuals who have experienced trauma and create a sense of “us versus them,” resulting in increases in conflict, violence, and a custodial rather than a therapeutic environment. With staff turnover and the absence of training for new employees, knowledge of 6CS practices was lost. The use of S-R rose again at a devastatingly high rate and reached even higher levels than at the start of the initiative.

Discussion, Recommendations, and Call for Regulatory Action

CMS and TJC provide minimum mandatory standards, regulations, and oversight for hospitals and other health care providers that are certified or accredited by CMS or TJC, respectively. Both agencies revised their expectations related to S-R after the 1998 Hartford Courant reports and the resultant congressional hearings in 2000. Both agencies, however, focused only on doing R-S better by developing additional regulations on staff training, oversight, and documentation expectations when S-R was used. What these two important agencies did not focus on, however, was how to prevent the conflicts and violence in inpatient settings that lead to the use of S-R. This narrow focus was understandable in 2001 and 2005, when the final CMS rules were published, because only preliminary data on S-R prevention were available. However, since then, CMS and TJC standards and regulations have not been revised or informed by current best practices or by the robust literature on evidence-based approaches to the prevention of violence and S-R use. As such, the maximum allowable duration of S-R orders still stands at 4 hours for adults, 2 hours for adolescents, and 1 hour for children, even though many facilities have greatly reduced these order times, which were not based on clinical criteria but rather on staff convenience. In addition, the regulation mandating a physician’s face-to-face review of individuals in S-R within 1 hour of the order was changed by CMS in 2005 (and later by TJC) to allow trained nurses to do so, but clear descriptions of the credentialing of these nurses were not provided. Staff training guidelines set forth by CMS encompass only vague competency expectations regarding deescalation and safe S-R application techniques instead of incorporating mandatory trauma-informed practices, such as teaching staff how to respond to the needs of individuals in treatment, prevent conflicts, and assist individuals in learning emotional regulation skills. In addition, the use of rigorous debriefing after every event is not mandated or codified in most states. Most concerning is that the use of prone restraint, a highly lethal practice, has not been prohibited.

Although CMS and TJC can mandate only minimum standards and must be accountable to their member agencies, they could do much more to compel U.S. psychiatric hospitals to use best practices that have been in place for more than 20 years. The evidence is clear that psychiatric hospitals can safely reduce and cease the use of S-R without increases in injury to staff or in the use of emergency medications, but doing so requires sustained adherence to best practices, as the Pennsylvania State Hospital System has demonstrated for decades. It is equally clear (and critically demonstrated by the cautionary tale of the hospital described in this article) that external mandates from regulatory agencies are needed to ensure widespread and sustained implementation of trauma-informed practices and cessation of S-R. CMS and TJC must update their regulations and offer a roadmap (guided by current evidence-based practices) toward the cessation of S-R practices, which are traumatizing and retraumatizing to staff and individuals in treatment and associated with an unacceptable risk for lethality.

CMS and TJC should update their definitions of both seclusion and mechanical restraints to ensure that all containment practices are reported as such. Seclusion is the involuntary confinement of a person to a room or isolated area from which they are physically prevented from leaving at will (regardless of whether the door is open or closed, locked or unlocked). Mechanical restraints refer to the forcible tying of a person with any device to a bed or chair or the use of ambulatory handcuffs or leg cuffs.

CMS and TJC should update their S-R regulations to follow best practices, which suggest that psychiatric hospitals should begin with the immediate cessation of the use of seclusion and prone restraint (a highly lethal practice), followed by a plan to reduce and eventually cease the use of mechanical restraints over 5 years. After the immediate cessation of seclusion and prone physical restraint, CMS and TJC should limit mechanical restraint use to only two- to four-point restraints in a stationary restraint chair (given the higher lethality of bed restraints in both the supine and prone positions) while the initiative to cease the use of mechanical restraints is under way. All other forms of mechanical restraint (including bed, net, and ambulatory restraints) should be ceased immediately.

CMS and TJC regulations should stipulate that there is only one indication for the use of mechanical restraints: as an emergency measure to prevent imminent physical injury to a person. This standard should be clearly defined to indicate that the threshold to use mechanical restraints does not include the following situations. First, mechanical restraints should not be used after an assault has occurred, no matter how severe the assault was, because such use would be punitive, not preventive. To reach the threshold, a physical blow must be imminent and preventable only through the use of mechanical restraint. Second, verbal threats of future violence do not meet the threshold. Again, a physical blow (not a threat) must be imminent and preventable only by mechanical restraint. Third, mechanical restraints should not be used in response to yelling, insults, spitting, throwing of feces or urine, agitation, pacing, jumping, shadowboxing, elopement, possession or use of contraband, etc. Only imminent physical violence meets the threshold. Finally, property destruction does not meet the threshold for the use of mechanical restraints. Only imminent physical violence to a person (not to property) meets the threshold.

CMS and TJC regulations should indicate that the criterion for removal of mechanical restraints is when the threat of imminent physical injury to a person—not a verbal threat—is no longer present. Because verbal threats are not an indication to place a person in restraints, they are not an indication to continue to hold a person in restraints. The restraints should be removed as soon as the individual is no longer physically struggling against the device.

The final recommendation for CMS and TJC is to monitor the removal of mechanical restraint chairs from units after a hospital has achieved at least 1 year of single-digit episodes of mechanical restraint use. In the authors’ experiences, when mechanical restraints are still available, they are likely to be used—even after extensive training and sustained success with noncoercive interventions.

Given the contrast of the sustained cessation of S-R in the Pennsylvania State hospitals via continued adherence to 6CS with the cautionary tale reported in this article of significant S-R reduction in a psychiatric hospital and the reversal of those gains after DOJ monitoring ended, the authors are calling for updated regulatory action by CMS and TJC. Regulatory mandates from CMS and TJC are the only way to ensure widespread adherence to evidence-based, trauma-informed practices and to achieve the cessation of S-R use in psychiatric hospitals.

In

Box 1 are recommendations to CMS and TJC for updating their S-R regulations for psychiatric hospitals with evidence-based best practices. In

Box 2 is a recommended 5-year roadmap for hospitals to achieve the cessation of mechanical restraint use, with benchmarks to be monitored during a hospital’s CMS and TJC accreditation and reaccreditation visits (

29,

30).