Despite plentiful evidence supporting effective treatments for mental disorders, access to these treatments remains limited in the United States. According to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, less than half of adults diagnosed as having psychiatric disorders received treatment for their illness (

1), in part because of shortages of mental health practitioners throughout much of the country, especially in underserved communities (

2–

5). In this context, primary care has increasingly become the de facto mental health care system in the United States (

6), with clinicians in this setting seeing 60% of patients treated for depression (

7) and prescribing 79% of antidepressant medications (

7).

Mental health workforce shortages are further complicated by the relatively small proportion of psychiatrists accepting insurance for reimbursement. Using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) between 2005 and 2010, one study estimated that 55.3%, 54.8%, and 43.1% of psychiatrists accepted commercial insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid, respectively (

3). In comparison, the corresponding percentages for all other physicians in 2010 were 88.7%, 86.1%, and 73.0% (

3).

Studies using “secret shopper” methods have reported that, even when psychiatrists are in network, only a small fraction are available to see new patients (

10). Furthermore, multiple studies have found that a disproportionate share of treatment for patients with mental disorders is delivered out of network (

1,

11) and that self-pay visits are more common for mental than general medical health care (

12). These trends have paralleled a proliferation of nonphysician clinicians (e.g., advanced practice nurses) in the mental health workforce (

13,

14).

This study aimed to use the restricted version of the NAMCS data set, which is not publicly available, to analyze acceptance of insurance among psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists and to examine the associations between specific physician characteristics and insurance acceptance.

Discussion

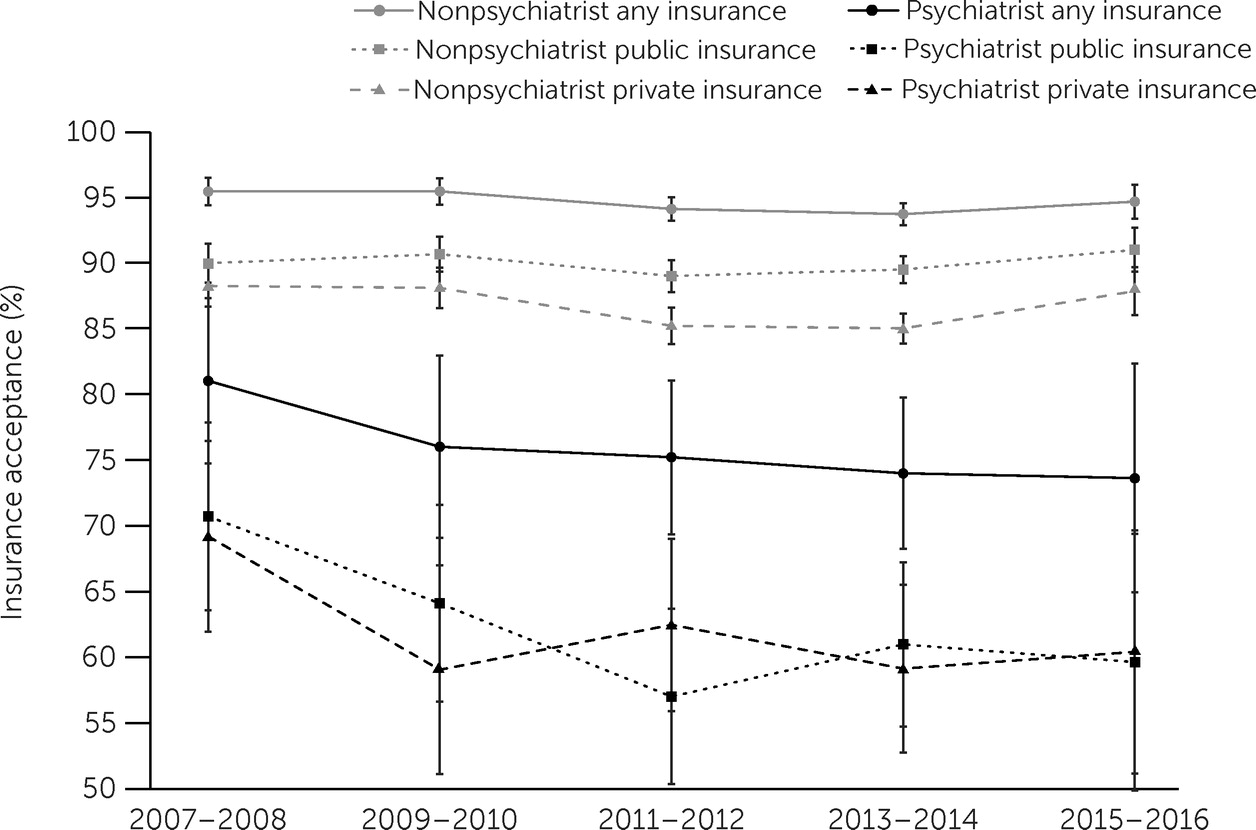

To our knowledge, this study is among the first to use variables available only in the restricted version of the NAMCS in order to analyze physicians’ acceptance of insurance. Our findings build on those of previous studies that used the public version of the NAMCS to address similar questions. This study is the first to report broad insurance acceptance trends for psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist physicians between 2007 and 2016. The percentages among nonpsychiatrists who accepted all sources of payment were higher than among psychiatrists. The gap in insurance acceptance between nonpsychiatrists and psychiatrists was wider for public than for private insurance. Among psychiatrists, those practicing in MSAs and those with solo practices were significantly less likely to accept private, public, or any insurance. These same trends were observed among nonpsychiatrists, although to a lesser extent.

Our finding that psychiatrists accepted insurance at rates notably lower than the rates among nonpsychiatrist physicians corroborates findings from previous studies, which found that psychiatrists’ insurance acceptance rates were lower for Medicare, Medicaid, and noncapitated private insurance between 2005 and 2010 (

3) and that self-pay was disproportionately represented in psychiatric relative to nonpsychiatric outpatient visits (

12). In our time-trend analyses, we found that differences in insurance acceptance between psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists, with few exceptions, were largely stable over time. Although we did not specifically evaluate Medicaid expansion, our results largely corroborate the finding from a recent study indicating that Medicaid expansion did not have a major impact on Medicaid acceptance among psychiatrists (

8). However, our results also differed from those of the same study in that we did not find that the gap in Medicaid acceptance between psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrist physicians has widened significantly (although we evaluated the 2007–2016 time frame, whereas the other study evaluated the 2010–2015 period) (

8). Most notably, we found that, although all physicians working in solo practices and those in MSAs were less likely to accept insurance than their counterparts in group practices and outside of MSAs, these trends were more pronounced among psychiatrists.

Much has been written about the individual and contextual factors that underpin psychiatrists’ lack of insurance acceptance and disproportionate acceptance of self-pay patients, relative to nonpsychiatrists. Hypothesized explanations include the relatively low reimbursement rates (

20) for mental health services (often lower than rates for nonpsychiatrist physicians for the same service [

21]), comparatively arduous administrative burden due to a lack of insurance parity enforcement (

20), the shortage of psychiatrists in many U.S. areas, and the low start-up costs associated with entering and competing in the mental health delivery market.

Our findings did not directly support any of these hypotheses or propose alternative explanations, but they have provided a higher-resolution description of the phenomenon, which may improve understanding of this problem. Our finding that psychiatrists in solo practices were less likely to accept health insurance than nonpsychiatrists practicing in the same type of setting was not surprising. Mental health reimbursement rates from insurers are comparatively low, and psychiatrists working individually have little administrative support or negotiation leverage with payers. Furthermore, relatively low supply and high demand in many areas of the United States provide a favorable environment for psychiatrists, who often quickly reach patient capacity through nascent cash-only practices without accepting patients from lower-reimbursing payers like Medicare or Medicaid.

Our finding that psychiatrists practicing in MSAs were less likely than nonpsychiatrists in the same areas to accept insurance was also not surprising. Current market conditions are especially favorable for psychiatrists in urban areas. Demand has soared while supply and insurance reimbursement for behavioral health care have failed to keep pace. Outside of MSAs, market forces remain favorable for psychiatrists because of high demand and extremely low supply, although perhaps not to the same extent as in urban areas.

Of note, in analyses with psychiatrists only, we confirmed the results of a previous study that psychiatrists in the Midwest region are more likely than those in the Northeast to accept any private insurance or any insurance (

3). Broadly, the psychiatrist-only analyses yielded findings similar to those comparing psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists. For example, findings for psychiatrists in MSAs mirrored those in the analysis comparing psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists in MSAs, indicating that practice in an MSA is one of the physician characteristics that was most consistently associated with insurance nonacceptance. Similarly, our results suggest that psychiatrists working in solo practices were substantially less likely than psychiatrists working in a group practice to accept insurance, a finding consistent with a previous study (

3). Further, when coupled with the results comparing psychiatrists with nonpsychiatrists, this finding suggests that physicians in solo practices and those in MSAs are generally less likely to accept insurance, although this difference is especially pronounced for psychiatrists.

The reluctance of psychiatrists to participate in insurance networks substantially threatens mental health access, equity, and public health. Although our findings highlight this problem more clearly than have previous studies, our observations cannot directly inform an overarching strategy to mitigate the deleterious market forces that have led to the inequities and inadequacies in the contemporary U.S. mental health care delivery system. We believe that the most effective solutions to this challenge could leverage the economic concepts of competition and regulation (

22). Specifically, the United States needs many additional mental health providers to increase competition, thereby reducing treatment prices and incentivizing insurance network participation. With current and projected shortages of psychiatrists, it is likely that such a supply increase would be driven by advanced practice nurses and physician assistants, especially for patients with common, low-acuity mental health problems. Indeed, this pattern has been shown in recent studies (

13,

14). It is also likely that primary care providers (PCPs) will continue to see most patients with behavioral health problems. Consequently, psychiatrists should be incentivized to use evidence-based approaches such as the collaborative care model to provide adequate training, consultation, and support to PCPs taking on this burden (

23).

On the regulatory side, federal and state governments should enforce parity legislation (

1). Payers would be held accountable for disparities in network adequacy between behavioral and general medical health care. This step would, in turn, lead to partial mitigation of factors, such as comparatively low reimbursement rates and disproportionately arduous nonquantitative treatment limitations (e.g., prior authorizations) that drive psychiatrists away from insurance networks (

1). Nevertheless, we note that psychiatrists will continue to have lower market entry costs than nonpsychiatrists and will therefore still have powerful incentives to practice individually and outside of insurance networks to maximize revenue and reduce administrative burden.

This study had several limitations. First, we had no data on why physicians did or did not choose to accept insurance. Therefore, our results were intended to characterize the extent of payment source disparities between psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists, as opposed to explaining precisely why these disparities occur. Additionally, the sample in this investigation included only physicians and excluded those practicing in hospitals, federal medical facilities, or community health centers. That said, the physicians surveyed in the NAMCS represented those who conduct approximately 90% of outpatient encounters in the United States each year (

3). Finally, the results of this study were limited by the relatively small number of psychiatrists surveyed in the NAMCS. Although our findings were weighted by using complex survey design methods to provide national estimates, the counts of psychiatrists were much lower than those for nonpsychiatrists.