In response to the crisis, practitioners and programs in many countries have been trying to overcome disruption to in-person psychological services by swiftly shifting to delivery of remote services (

1,

7). This is true in both HICs and LMICs, where a range of innovations for remote delivery has been implemented (

8), including the provision of psychological interventions through task-sharing or collaborative care models by nonspecialists (e.g., persons without a mental health professional degree, such as community health workers or members of community-based organizations) (

8–

10).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, international application of remote delivery of psychological treatments, and telemedicine in general, was limited and varied considerably (

11). Since the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries and regions have expanded their use of telemedicine to include psychological support. In a recent survey, 37% of 112 countries reported using telehealth technologies for mental health consultations (

12). Despite the ongoing stark “digital divide” in online access or digital smartphone applications that exists in LMICs compared with HICs (

13), training for and delivery of remote psychological support have been occurring globally (

14–

18), including for synchronous delivery, such as through urgent telephone calls via suicide or emergency hotlines and delivery of brief, evidence-based interventions over a video or telephone connection (

19). Global initiatives have been launched with aims to support practitioners in adapting typical in-person psychological support and treatments to remote formats, particularly for synchronous practitioner-client care (e.g., direct care to a client via video or telephone connection, not including asynchronous methods such as Short Messaging Service [SMS], e-mail, self-help applications, or digital interventions) (

20,

21).

For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) now provides brief e-learning courses on preparing for remote delivery of psychological support, highlighting unique considerations for remote services, such as distinct confidentiality issues, assessment of suicide, variation in verbal and nonverbal communications, and issues around technology and connectivity (

www.whoequipremote.org). Similar initiatives include the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s release of guidance and operational considerations for implementation and delivery of remote mental health and psychosocial support programming across sectors (

22) and the rapid distribution by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies of the manual

Remote Psychological First Aid During the COVID-19 Outbreak, which provides brief guidelines on using basic helping skills remotely to help people dealing with distress, primarily through voice-only connections, along with an online training package for teaching the skills (

17,

23,

24).

The global adoption of remote psychological support and treatment delivery prompted by this crisis is predicted to continue a strong growth trajectory, and practitioner training in remote technologies has been encouraged (

25). This training is particularly important in areas where COVID-19 has exacerbated existing inequities in mental health care. Approaches to training and supervision that support high-quality service provision in addition to availability of services and that are deployable in low-income settings must be prioritized (

26,

27). Many global sectors identify the measurement and monitoring of practitioner competency as a key ingredient to ensuring high-quality care. Current examples include the not-for-profit physician-led organization, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which established core competencies required for “every resident and practicing physician” in the United States (

28), and the ongoing consultation work led by the WHO for drafting the

Global Competency Framework for UHC to establish required competencies for primary health care workers globally (

29). However, conceptualization and application of competency and competency frameworks are mixed within and across sectors and countries, thereby limiting common understanding and implementation into practice on a global level (

30).

Given the growing number of resources being developed for remote-specific adaptations for psychological support, it is important to recognize the advantages and disadvantages of adapting in-person care techniques for use with remote modalities and to consider whether there are competencies that support synchronous remote delivery that could be fundamentally different from those used for in-person care. Therefore, we conducted a rapid review to identify the skills currently recognized as foundational to remote delivery of any psychological service, how they are described, and how they can be harmonized.

Methods

In this article, we use the term “remote psychological support”—also referred to as tele–mental health, tele–behavioral health, telepsychology, or teletherapy—to refer to the use of synchronous telecommunications, such as telephone and voice-only or videoconferencing connections, to deliver psychological interventions and associated mental health services by a specialist or nonspecialist practitioner directly to a client or patient

. The term psychological support is more frequently used in global settings to capture the increasing use of task-sharing initiatives whereby trained and supervised nonspecialist practitioners deliver care. Task-sharing models are particularly prevalent in LMICs, where the gap between those in need of services and those who have access to such services or available resources is almost 90% (

31,

32). Using a simplified systematic methodology, we conducted a rapid review to enable timely identification of competencies and inform ongoing delivery of remote psychological support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rapid review methods are similar to those of systematic reviews but are adjusted in a range of ways based on the topic and assessment needs in order to facilitate a streamlined approach to synthesizing evidence within a limited time frame. These reviews are often conducted to support decision making for program implementation or service delivery efforts responding to emerging needs or urgent matters—for example, humanitarian crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (

33,

34). Systematized guidance on conducting a rapid review is mixed (

33), and a PRISMA checklist for standardizing rapid review processes is not yet available (

35). Therefore, for this rapid review, we chose to adhere as closely as possible to a systematic review process in a limited time frame, including registration of a protocol on February 25, 2021 (PROSPERO, CRD 42021242534; Open Science,

https://osf.io/s4b7m/), to clearly report our methods. We referred to previous reviews in similar areas for expansion of search terms related to remote mental health services (

36,

37).

Operational Definition of Competency and Competency Measurement Type

We specified the operationalization of competency and competency measurement to promote conceptual clarity and comparability with existing frameworks and methods in this field. Mills and colleagues (

30) defined competency as “The observable ability of a person, integrating knowledge, skills, and attitudes in their performance of tasks. Competencies are durable, trainable and, through the expression of behaviors, measurable.” For this review, we focused on literature that highlights competencies that can be measured through observation, such as through standardized role-plays, a method that has been suggested over other competency measurement types (e.g., knowledge tests) (

38,

39). This operationalization is consistent with freely available competency-driven training resources (

40), and thus we anticipate that the results of this review can align with globally centered initiatives and can support the standardization of more equitable and less bespoke practices (e.g., specific to a certain organization, association, or setting) for measuring and monitoring competency. Moreover, competency evaluation approaches that use observational measurement with role-plays offer an assessment process distinct from quality and fidelity assessments that use live sessions (

41) and may increase a practitioner’s confidence and competency achievements prior to real-world delivery when such approaches are included in training and supervision (

42–

45), which aligns well with our overall aims for this study.

Study Identification

On February 26, 2021, we searched Scopus, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO for published literature and guidelines for descriptions of competencies related to delivering remote psychological support during synchronous sessions and that are observable through direct practitioner-client interactions, such as skills unique to remote settings that can improve communication over remote modalities (e.g., technology skills), skills for optimizing interactions during voice-only or video-based interactions (e.g., using telephone or videoconferencing), or other foundational practitioner competencies that may be used for in-person services and have been adapted or modified for remote delivery (e.g., nonverbal communication, practices to ensure safety and privacy). We limited our search to peer-reviewed articles, published in the English language between 2015 and 2021, and we included any relevant articles identified during full-text review. (A sample search strategy is presented in the

online supplement.) Database results were initially imported into EndNote X9 (

46), a reference management system, and then imported into Covidence (

47), a Web-based software platform for streamlining systematic reviews, for removal of duplicates, screening, and data extraction.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created and agreed upon by two authors who are experts in systematic reviews and competencies (G.A.P., B.A.K.) (see

online supplement for details). We included articles that focused on or included competencies involving practitioners or practitioners-in-training over age 18 who were delivering any mental health–related intervention or care and who included a session or component of synchronous remote connection for direct practitioner-beneficiary interaction over video-conferencing or voice-only platforms. We excluded articles that focused on or had competencies involved with in-person delivery components, non–mental health–related interventions or care, asynchronous treatments or intervention components, or treatment-specific techniques or competencies and components otherwise not observable through practitioner-client sessions or not adaptable or modifiable to remote scenarios. Screening processes were streamlined to one author-reviewer (G.A.P.), who conducted title and abstract screening and full-text screening and who conferred with a second author-reviewer (B.A.K.) regarding any discrepancies. To support rigor, a third author-reviewer (K.A.P.) confirmed exclusion of full-text articles. During full-text screening, if an article included mixed components of remote and in-person delivery or common and treatment-specific techniques, it was included for the extraction stage.

Data Extraction and Analysis

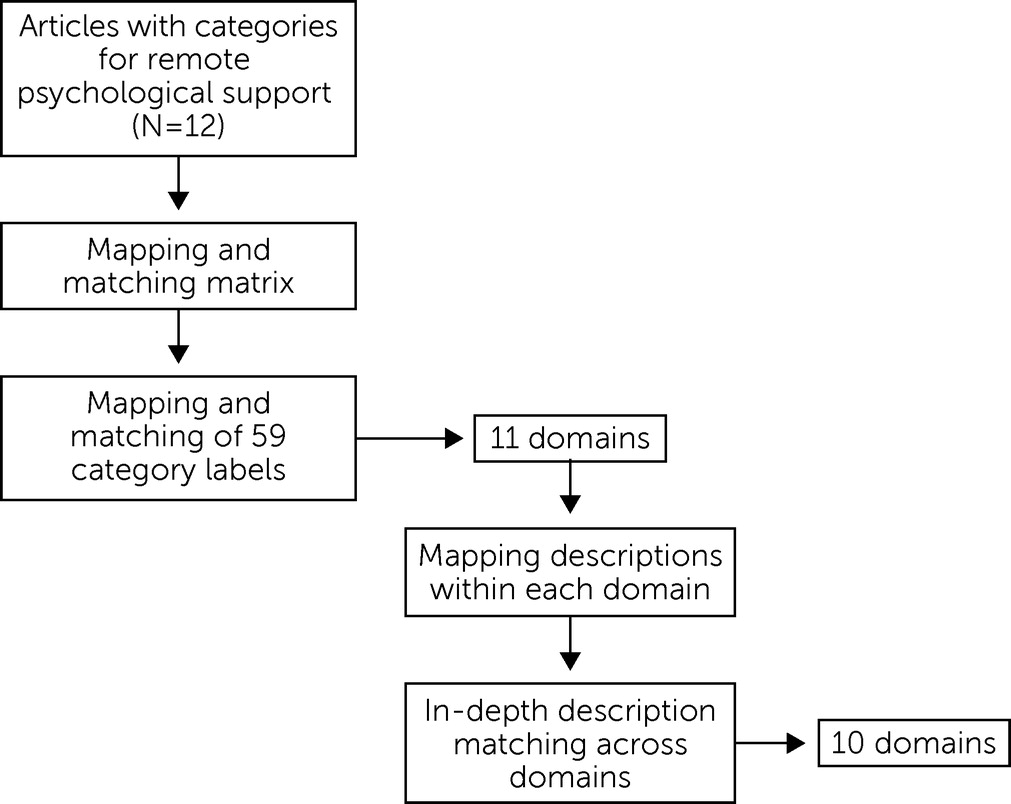

Predetermined extraction criteria for each eligible article included general study information (study design and type, setting, and population type for providers), label and description of guideline or skill, and any behaviors or other attributes included with the description. Iterative creation of extraction criteria was optional if other relevant information presented itself throughout the extraction process. These categories were inserted into Covidence, and one author (G.A.P.) carried out the initial extraction of the included articles. Any data related to the inclusion and extraction criteria were extracted, regardless of whether the article had mixed components—e.g., synchronous and asynchronous or remote and in-person delivery. To ensure accuracy in reporting, any surrounding information that may have supported comprehension of or that gave additional context to the criteria-matched data was also extracted. Another author (K.A.P.) checked the extracted data for accuracy and consistency by using the “check data” form in Covidence, which allows for direct comparisons per category and corrections as needed alongside the article being extracted. Final data were exported from Covidence into a spreadsheet to prepare for analysis, wherein an in-depth mapping and matching exercise was conducted to identify and consolidate core skill domains across articles. The mapping and matching exercise was done in three stages: mapping and matching labels of competency categories extracted from the articles to create overarching domains, mapping the corresponding label descriptions within each domain, and in-depth description matching across domains.

Results

The search identified 135 articles. Twelve articles met inclusion criteria (

48–

59). (A flow diagram of the identification process is available in the

online supplement.) Study types included guidance documents (e.g., guidelines, program guidance overview, and in-depth guidance commentary; N=5) (

48–

52), narrative reviews (N=3) (

53–

55), a scoping review (N=1) (

56), a task force review of guidelines (N=1) (

57), a case series (N=1) (

58), and a feasibility study (N=1) (

59). All studies took place in HICs. Most were reported from the United States and Canada (N=11), and one study was reported from Saudi Arabia (

57). Each article focused its guidance or considerations on practitioner conduct or training principles for specialist practitioners or professionals or on trainees or students in a prelicensure or professional program; all were working with adult populations. Within the scope of their work, the authors of seven articles (58%) referenced the American Psychological Association’s telepsychology guidelines (

48,

50,

56,

59), and three articles (25%) referenced the ACGME requirements for training and preparing resident and fellow physicians (

48,

53,

54). Four articles mentioned work with youth populations; these articles suggested that the same procedures used with adults be followed with modifications as needed, such as paying attention to youths’ developmental status (

48,

49,

51,

52). Summary descriptions of included articles can be found in

Table 1.

Identification of Competency Categories Related to Remote Psychological Support

Four articles (33%) provided an operational definition of competency, with definitions differing across the articles (

48,

53,

54,

58):

“Professional competence can be viewed as the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community served. Competence requires that practitioners possess the knowledge and skills needed to ensure meeting minimum expectations for the quality of professional services provided.” (

58)

“ACGME defines milestones as competency-based developmental outcomes (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, and performance) that can be demonstrated progressively by residents and fellows from the beginning of their education through graduation to the unsupervised practice of their specialties.” (

48)

Only two of the 12 included articles (17%) referenced competency measurement, both of which included observational measurement through simulation methods, but there was not a universally preferred method of measurement across articles (

53,

59).

A total of 59 competency categories with descriptions of knowledge, attitudes, or skill sets related to remote psychological interventions were identified across articles, ranging from two to eight categories per article. Terminology and framing varied across articles, such as using direct labeling (“skill,” “competence,” or “competency”) with or without the related stage or topics of remote psychological interventions (e.g., “Competency 1,” “general telemental health competence,” or “telepsychology technical skills”) (

42,

50,

58), omitting any reference to “skill” or “competency” and referring only to it as a scenario, domain, or stage in practice (e.g., “client care,” “management and treatment planning,” or “telepsychology practice domain”) (

49,

53,

56). Some articles used a category such as “best practices” to describe behaviors or actions (e.g., “Examples of best practices include the use of settings in which the patient’s video screen should not include picture-in-picture because self-reflected image can inhibit the patient’s communication”) (

59).

Within and across articles, descriptions of competency categories varied in style (e.g., checklists and paragraphs), detail, and length (e.g., in-depth descriptions with five to seven sentences or four or more bullets or brief descriptions using one or two bullets or a phrase). All articles included either operative descriptions (N=10, 83%) or some reference to a behavior that a practitioner could show an observer. Descriptions utilized present or past tense, or sometimes both, and sometimes included both unobservable (e.g., completed before or between sessions) and observable (e.g., performed during a session with a client or patient) knowledge, attitudes, or skills in a sequence of events involving multiple interactions or timepoints. For example, “Within their knowledge of local resources, providers should have knowledge of or be acquainted with local in-person and emergency resources” (

56); or “Technological competence includes possessing adequate knowledge of and familiarity with the various technologies being used in the practice of tele–mental health. . . . Practitioners should possess adequate familiarity with systems used so that they can make needed adjustments to settings used to ensure that auditory and visual quality are sufficient for optimal professional services to be provided as well as to provide instruction to clients on the use of these systems” (

58). (A table in the

online supplement presents other examples of various description types from four articles.)

Harmonization of Core Skill Domains

The 59 competency categories from each article were inserted into a matrix to guide the mapping and matching exercise for identifying core domains (

Figure 1). After label mapping and descriptive mapping, we generated a consolidated list of 10 domains common across articles.

Table 2 presents the domain name, general description of the domain, and the referenced articles that contributed to the domain creation. The 10 domains included remote-specific skills (e.g., use of technology during remote delivery) and skills that can be used for in-person delivery with varying degrees of adaptation for remote settings (e.g., communication skills). The domains were prioritized by the number of articles mentioning the guidance and are as follows: emergency and safety protocols (N=10 articles), facilitating communication over remote platforms (N=8), remote consent procedures (N=7), technological literacy (N=7), confidentiality and privacy during remote services (N=7), practitioner-client identification for remote services (N=5), verbal and nonverbal communication during remote services (N=4), engagement and interpersonal skills for remote services (N=4), establishing professional boundaries during remote services (N=4), and encouraging continuity of care during remote services (N=1). Although harmonization into domains was possible, descriptions from articles varied within domains. Examples of these description variations are presented below (a table with exact descriptions per article per domain is available in the

online supplement.)

Domain 1: Emergency and safety protocols during remote services.

All 10 articles (83%) contributing to this domain had some description related to a practitioner’s ability to screen for risk of or handle emergencies (

48,

51–

59). Seven of the 10 articles (70%) included reference to having a protocol or plan in place or included action steps to determine risk, such as, “Check on need for an emergency protocol,” “a plan for addressing acute safety issues,” and “Providers should have protocols in place.” Seven articles (70%) included specifications for practitioners’ knowledge of local resources, “Must be aware of local emergency resources,” or of a service or “back-up” local to the client or patient. Two of these seven articles also included guidance for practitioners to discuss with clients or patients the “importance of having consistency” in location and for practitioners to be aware of their location and any changes to ensure relevant emergency resource knowledge.

Domain 2: Facilitating communication over remote platforms.

The eight articles (67%) included in this domain all had some reference to the practitioner’s creation of an environment that can enhance engagement with the client (

50–

53,

55–

57,

59). Five of the eight articles (63%) had specific descriptions to address placement and height of the camera at an “ideal position” with “face clearly visible to the other person” and “close to the patient’s eye level.” Two articles (25%) had instructions to turn off the picture-in-picture feature on the client’s side. Three (38%) directed the practitioner to secure an agreeable physical environment on the sides of both the practitioner and the client by using “well-placed lights.” Three (38%) had general guidance for “maximizing comfort” or to “minimize distractions” or “clarify and amplify communication.”

Domain 3: Remote consent procedures.

The seven articles (58%) in this domain included descriptions of addressing and discussing with the client the nuances of consent procedures as consent relates to remote delivery (

49–

52,

55–

57). This included four articles (57%) with guidance for the practitioner to explain “benefits, risks, and limitations” related to remote psychological support, such as drawbacks to not being able to see full body language, potential Internet security breaches, or, in the case of one article, discussing circumstances for discontinuation of remote services if they can no longer be provided safely. Three of the seven articles (43%) had guidance for discussing possible alternatives to remote support and for establishing expectations for client-practitioner interactions in and outside sessions.

Domain 4: Technological literacy.

The seven articles (58%) in this domain had skill descriptions regarding the practitioner’s level of knowledge and familiarity with technology and the practitioner’s skill set for clearly communicating with and guiding the client through such mediums (

50–

52,

55–

58). Guidance included making technical modifications with devices or Internet connections, such as adjusting volumes and checking microphones, cameras, video display, and wiring for a strong Internet connection on both receiver ends (N=5 articles, 71%), assessing the client’s comfort and past experiences with technology or videoconferencing (N=2, 29%), maintaining communication about potential issues and disruptions with remote modalities (N=2, 29%), and establishing a back-up plan in case of disruption (N=2, 29%).

Domain 5: Confidentiality and privacy during remote services.

Seven of the 12 articles (58%) included descriptions of ways practitioners may address confidentiality and privacy processes or issues during remote services (

48,

49,

53–

56,

59). These typically involved adjustments to existing in-person confidentiality and privacy procedures, such as “Use telepsychology regulations, and if none, apply judgment to convert in-person ones,” or additions to existing laws, such as a practitioner’s conducting a standard HIPAA privacy and security discussion with the client while also adjusting “behavior context, e.g., institutional, local, regional,” or additionally explaining how “digital health information will be protected and kept from outside interference during the course of telephone, video, email, or text-based therapeutic services.” Some articles had descriptions of specific adjustments the practitioner could make to enhance and ensure privacy, such as “using head-phones” or “adding white noise,” planning sessions when children can be supervised by others, and moving the camera around to show the practitioner’s space to the client.

Domain 6: Practitioner-client identification for remote services.

Five of the 12 articles (42%) included steps or guidance for practitioners to identify themselves and clients before remote services begin or during the first session of remote treatment or services (

51,

52,

55–

57). Among these articles, identification methods included having introductions or verification of the practitioner’s and client’s identity (N=5 articles, 100%), introducing other parties present on both sides (N=1, 20%), providing the practitioner’s certification or credentials (N=4, 80%), confirming the location of the practitioner (N=2, 40%) and of the client (N=3, 60%), and exchanging immediate contact information between the practitioner and the client (telephone, text, or e-mail) and other relevant support people (N=2, 40%).

Domain 7: Verbal and nonverbal communication in remote services.

In four articles (33%), authors gave suggestions and guidance on ways that practitioners could facilitate clear verbal and nonverbal communication during remote services (

48,

50,

54,

57). Nonverbal communication recommendations varied across the four articles and included having an “appropriate appearance” or “appropriate posture” or presenting as “well-appearing”; instructing the practitioner to “listen more and speak less”; listing options for how the practitioner can make facial expressions “very clear to the client,” such as zooming the camera in on the practitioner or the client’s face or zooming out for a better view of the client’s body language; and, more generally, instructing the practitioner to “optimize one and other’s telepresence.” Verbal communication recommendations were identified in two of the four articles, either with specific instructions (e.g., “ask open questions” and “summarize outcomes”) or more broad instruction to the practitioner to “amplify communication (i.e., 15%) based on video literature” and to “trouble-shoot communication difficulties.”

Domain 8: Engagement and interpersonal skills for remote services.

We identified four articles (33%) that explicitly referenced behaviors that a practitioner could perform to enhance rapport building and therapeutic alliance, although these behaviors sometimes overlapped with the verbal and nonverbal communication domain (

52–

54,

57). References were made for the practitioner to “establish therapeutic alliance, build trust and rapport” and to “adjust to technology (e.g., replace handshakes with verbal comment)”; guidance was provided for the practitioner to be attentive to technology and how it affects “patient rapport and communication.”

Domain 9: Establishing professional boundaries during remote services.

Four articles (33%) covered guidance on ways that practitioners could mitigate ambiguity in professional boundaries that arises during remote services (

48,

51,

52,

56). Suggestions for practitioners varied from general statements, such as for the practitioner to describe the “appropriate interpersonal and online relationship boundaries,” to more specific suggestions. Specific suggestions involved practitioner guidance to discuss and document with the client when and how the practitioner will communicate, including detailing the technology medium (e.g., video, text, or e-mail); business hours and response times; and when, where, or whom to contact in an emergency. Issues involving a practitioner’s personal and professional social media presence and clear boundaries on these platforms were also mentioned in one article.

Domain 10: Encouraging continuity of care during remote services.

One article (8%) covered the topic of the importance of a practitioner’s encouraging continuity of care during remote services, particularly to cover remote-characteristic services, such as a brief call or a single session (

55). The authors of this article emphasized that “Even if the telepsychiatric meeting is a single appointment, the psychiatrist is responsible for giving the patient clear guidance about what to do next.” They also offered options to address levels of urgency with “reasonable actions,” such as managing this step with a “relatively healthy and well-functioning patient” by advising the person on how to find a referral and with “a patient with emergent clinical needs and significant risk factors,” which may require the practitioner to schedule a follow-up appointment to check in with the client.

Discussion

We conducted a rapid review to synthesize evidence of observable competencies for remote psychological support services to aid in decision making and program implementation for training and delivery of remote psychological support during the COVID-19 pandemic and thereafter. Observable knowledge, attitudes, or skills unique to remote delivery with adult clients and in-person knowledge, attitudes, or skills modified for remote delivery with adult clients were identified across 12 peer-reviewed articles. Operationalization and framing varied across articles, which supported the need for the harmonization procedure in this rapid review. We did not identify any published literature from LMICs for this review, and thus our results are limited to high-income settings. Consequently, the core skill domains may capture techniques or processes that may need adaptation for the technical, logistical, legal, social, and cultural contexts wherein roughly 85% of the world’s population lives (

32). For example, issues related to confidentiality and the practical elements that constitute privacy during remote services are likely to vary dramatically and are not well represented by the seven articles identified in this review. Moreover, although the skill domains described in this review pertain to unique aspects of using remote modalities to deliver psychological support, the standard of clinical care provided should ideally meet the accepted requirements for the given treatment setting.

Many of the guidelines and considerations found in the articles were tailored toward existing organizational structures, practices, ethics, and laws, which may represent a barrier to generalizing these competencies, especially in the case of nonspecialist practitioners who are not typically connected to professional mental health associations. For example, several articles in this review offered guidance on ethical and legal compliance, primarily around health laws based in the United States (e.g., HIPAA), which may not be relevant for training in other settings and may create obstacles for implementation of psychological interventions designed for humanitarian settings that encourage multisectoral coordination for a whole-person and whole-society approach to mental health (

60). Other skills identified in articles were specific to a particular setting, such as inpatient units, or for remote care that takes place within a specific organizational infrastructure (e.g., delivered in supervised emergency settings at a hospital or delivered in tandem with trained technical specialists). Moreover, because of their length, some of the guidance and competency frameworks in the included articles may not be feasible to implement in lower-resourced or humanitarian settings or in emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, given the already extremely short timelines and lack of funding and human resources.

A recent survey found that almost 50% of the countries that promptly adopted remote psychological support to address disruptions to in-person services due to COVID-19 were low-income countries (

61). Yet only 35% of those living in low-resource countries have Internet access, compared with 80% in higher-resourced countries (

62); telecommunication status ranges widely across global regions in terms of policy, innovation, infrastructure, and technology (e.g., digital apps and video consultation platforms), with advancements predominantly being led in high-income settings (

11). Although digital technologies are rapidly progressing in high-income settings and changing the way in which therapy is delivered (e.g., self-help digital applications and virtual reality) (

63), a cooperative effort must be made to meet the varying social, environmental, and resource needs and to inform optimal use of remote delivery methods (

13,

64).

As such, more evidence on implementation, training, and delivery of remote psychological support and related competency assessments in low-resource countries is needed to fully capture key competencies that support safe and effective remote care and to inform best practices for remote delivery. In terms of competencies for synchronous remote modalities, such as video connections or voice-only with telephones, standardizing the use of common definitions, applications, and measurement strategies could be a start. For example, having clear distinctions of how to measure competency alongside the framework and formatting competency descriptions with concise, simple descriptions of actionable behaviors could enhance adaptability and feasibility of implementing observational competencies into practice across an array of global organizations and programs.

Also, future research on and implementation of competencies and assessments would ideally align with current global initiatives that offer and promote the use of competency assessment tools that can be measured observationally, such as those paired with structured role-plays. An initiative led by the WHO and UNICEF called Ensuring Quality in Psychological Support (EQUIP) (

www.equipcompetency.org) aims to improve the competence of practitioners and the consistency and quality of psychological support training, supervision, and service delivery by providing resources, tools, and guidance for assessment and enhancement of essential competencies and use of competency-driven approaches in training and supervision programs (

40). EQUIP supports competency tools paired with standardized role-plays for observational assessment, such as the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) tool (

65,

66) that covers foundational helping skills (e.g., communication, empathy, rapport building, and confidentiality) in the delivery of psychological support to adults, including among nonspecialists and for manualized interventions (

67). ENACT has been widely implemented in a range of countries and humanitarian settings (

40,

68–

72) and has been successfully used in remote training of nonspecialists for delivery of a brief psychological intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic (

19). The

online supplement contains a draft observational evaluation tool for remotely delivered psychological interventions (ENACT-Remote) that training and implementing organizations can pilot test for remote competency assessment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and other expansions of tele–mental health services.

This review had some limitations. Because it focused only on common competencies that are observable during a practitioner-client interaction in a remote session, the goal was to address individual-focused competencies that are not tailored to certain licensures, treatments, programs, or organizational infrastructures. Therefore, we specifically designed our protocol to exclude identification of certain skills and competencies from this review and cannot report on them at this time: “higher-order” or “internal” skills (e.g., conceptual decision making, reflection, and mindfulness), skills that are not directly observable during synchronous care (e.g., competencies demonstrated between sessions or prior to or after a session or certain knowledge or certain attitudes), skills that are related to therapeutic change but likely remain consistent for remote or in-person sessions (e.g., promoting hope and providing psychoeducation), and tailored skills (e.g., treatment, organization, and infrastructure specific). Furthermore, this review did not identify skills specific to practitioners who work with youths, and thus our results are limited to practitioners who work with adults. We recognize the benefit of these areas and encourage our fellow researchers to explore these areas further, such as reviewing existing child-focused competencies and competency frameworks available in both high-income and low-income settings that could be used for remote settings (

73,

74).

Because of the rapid nature of this review, we limited our search to three databases and did not include gray literature. In addition, the evidence identified and summarized in this review is limited to high-income settings. Therefore, we cannot say we have comprehensively represented all core skill domains for remote psychological support nor have we refined them as discrete observational competencies useable in observational assessments. We have summarized and distilled results from only the published literature. Future exercises, such as a Delphi process wherein a group of field experts could participate in several rounds of surveying, could be considered to support consensus among these skill domains, along with other research studies and exercises involving implementation across more diverse global settings. Furthermore, the processes of this rapid review did not include an assessment of the quality of each included study, and thus we cannot determine the overall quality of the evidence at this time. Although this review highlighted core skill domains identified for the synchronous delivery of remote psychological support, it cannot be generalized for asynchronous methods.

As the field of remote psychological support develops, identifying competencies used in asynchronous methods and how these pair with the skill domains identified in this review could be beneficial for supporting enhanced and effective remote delivery of care. For example, identifying core skills around the use of digital applications or SMS messaging between sessions that support consistency during delivery of synchronous remote psychological support or that strengthen treatment adherence and relationship building when hybrid techniques are used (in-person and remote sessions) would be an important step in this field.