A total of 46,000 suicide deaths were reported in the United States during 2020, representing an increase in the annual mortality rate of more than 35% since 2000 (

1,

2). Suicide has been the 10th leading cause of death during this period, and the burden is especially acute among veterans (

3), people from sexual and gender minority groups (

4), and tribal populations (

5). In response to this ongoing public health crisis, multiple prevention resources to identify and aid at-risk individuals have been put in place, including crisis hotline services. Although program evaluations suggest that crisis hotlines play an important role in suicide prevention (

6,

7), little is known about the national coverage of crisis hotline services in relation to local need. With the launch of a nationwide suicide prevention and mental health crisis number (988) in July 2022, addressing this knowledge gap has a renewed urgency (

6,

8).

In this report, we describe trends in utilization of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline during the study period and hereafter referred to as the Lifeline;

https://988lifeline.org) alongside trends in suicide mortality burden. Funded by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Lifeline is a large network of more than 200 around-the-clock crisis call centers and is the primary telephone psychiatric hotline in the United States, providing confidential mental health crisis and counseling services. Calls made to the Lifeline are routed to the network center closest to the caller, and they are rerouted to national backup centers when local centers have reached capacity. Call centers are staffed by trained counselors who undergo a certification process or attain licensing from an external body before becoming part of the network.

Here, we report results from our analysis of calls to the Lifeline during 2007–2020 in relation to state suicide mortality rates. We hypothesized that Lifeline call rates would be correlated with the magnitude of suicidal ideation in a state and that, when studied alongside suicide mortality rates, Lifeline call rates would serve as a measure of unmet need for suicide prevention services. We identified trends in these two measures, categorized states by their similarity in trends, and identified states that could be prioritized for additional crisis centers or related mental health prevention services.

Methods

We identified suicide deaths reported to the National Vital Statistics System with

ICD-10 underlying cause-of-death codes (X60–X84, Y87.0, U03) (

9) from 2007 to 2020. To adjust for differences in age-sex-race distribution across states, we estimated standardized state mortality rates by using bridged-race population estimates (

10–

12) and the age, race, sex, and state of residence of the decedents. Because the study used retrospective, deidentified data, institutional review board approval was not required.

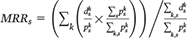

A state’s standardized mortality rate was calculated as

, where

denotes the population in group

k and state

s in a given year and

denotes the corresponding suicide deaths (the time subscript was dropped for notational simplicity; all calculations are annual); hence,

is the group-specific crude mortality rate in the state, and

is the proportion of the national population that belongs to group

k (

12). Here,

k=72, representing a stratification of each state’s population into nine age groups (5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years), two sex groups (male and female), and four racial groups (White, African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander), consistent with bridged-race grouping. (A comparison showing state-level crude mortality rates and standardized mortality rates is available as the first

online supplement to this report.)

Annual state mortality rate ratios (MRRs) were calculated as

, where the numerator is the state’s standardized mortality rate and the denominator is the national crude mortality rate. An

indicates a higher suicide mortality rate in state

s during year

t than would be expected if the state had the same age-race-sex distribution as that of the United States overall.

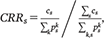

Lifeline call volumes were made available to the authors under a restricted-use agreement with Vibrant Emotional Health. All calls routed to one of the Lifeline centers from 2007 to 2020 were resolved to the origin county (inferred from the calling number) and were aggregated to calculate annual national and state call volumes. For each state and year, call rates per 100,000 population and call rate ratios (CRRs), a measure of the state’s annual per capita call rate relative to the national per capita call rate, were estimated. Analogous to mortality rates described earlier, if

cs denotes the call volume from state

s, the crude calling rate for state

s is

and the national rate is

. Given

, a

indicates that residents of state

s accessed the Lifeline at a higher rate than the national average during year

t. Unlike mortality rates, standardization of Lifeline call rates was not possible because demographic characteristics of callers were unavailable.

As a measure of state-level heterogeneity in CRRs and MRRs, we calculated the interquartile range (IQR) across states in each year of the study period. IQR is easily interpretable, is a robust measure of dispersion, and is less sensitive to extreme values than standard deviation. A change in heterogeneity would result in a statistically significant monotonic trend in IQR, as verified with the Mann-Kendall test. Furthermore, to assess change in a state’s CRR and MRR relative to other states over the study period, we grouped states into octiles by their annual CRR and MRR. The number of group transitions by a state is interpreted as a measure of consistency in crisis hotline use (CRR) or suicide mortality (MRR) relative to other states.

Results

During the study period, a cumulative 13.6 million calls were routed to Lifeline call centers, and the national call rate per 100,000 population increased from 151 in 2007 to 579 in 2020. The IQR of state CRRs decreased from 0.36 to 0.28, suggesting a narrowing of differences among states, and the decreasing trend was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001) (see first online supplement). Correspondingly, the national suicide mortality rate per 100,000 population increased from 12.3 in 2007 to 14.8 in 2020 (cumulative deaths=588,122); however, no significant trend in IQR was observed (p=0.51), with IQR remaining at 0.31, on average, for 2007 and 2020.

Many year-to-year transitions between CRR groups were observed over the study period (see first online supplement and second online supplement). Although a few states were consistently in the same octile group throughout the 14-year period (e.g., Alaska, Maine, Massachusetts), 40 of the 50 states were in four or more octile groups during the study period (mode=4). This finding suggests considerable variability in hotline utilization across states relative to each other, independent of an increasing overall trend. In contrast, octiles of state MRRs remained largely unchanged, with 35 of the 50 states in three or fewer groups (mode=2; see first online supplement and second online supplement).

On examination of CRR and MRR together, a few broad categories of states emerged (see first online supplement). About one-third of states (Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming) showed a consistently high MRR and a low CRR, suggesting high suicide burden and relatively low Lifeline use. Conversely, a few states (California, Illinois, Maryland, and Massachusetts) exhibited a low MRR and a high CRR, suggesting a relatively low suicide burden, either because of or independent of high Lifeline usage. Finally, several western states (Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Oregon) experienced a high CRR and a high MRR, and some middle Atlantic and southern states (Delaware, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) had declining Lifeline usage over the study period.

Discussion

The combination of low CRR and high MRR can be interpreted as a measure of unmet need for crisis hotline services. With the recent launch of the national suicide and mental health crisis number (988), states consistently exhibiting low CRRs and high suicide MRRs should be prioritized for increased messaging and outreach. Although alternative strategies based on population-level characteristics (e.g., states with the highest number of suicide deaths) may yield greater reductions in the number of suicide deaths, a balanced approach that integrates need-based metrics, such as those presented here, is necessary to ensure more equitable access to treatment. Additional analyses to evaluate complementary mental health services in high-need areas and modifiable barriers to these services, especially in high-risk population subgroups, are also required.

Identifying population-level drivers of the shared patterns among states requires more detailed analyses incorporating socioeconomic indicators, state-specific policies, budgeting for mental health services, and cultural factors that could affect willingness of individuals with mental health needs to seek help. Such analyses may help extend the categorization to states not currently grouped into any of the broad categories described earlier. Furthermore, caution is warranted in interpreting the strength and direction of causal associations between call volumes and suicide mortality because these links are complex and difficult to discern in ecological analyses.

This analysis also does not address individual-level drivers of differential utilization of Lifeline services; in addition, caller demographic information (age, race, sex, employment status, etc.) and mental health history (diagnoses of major depressive disorder, anxiety, etc.) can potentially inform in-depth analysis of barriers to access. Collecting such information in a manner respectful of caller privacy remains a challenge.

The rollout of 988 was expected to increase call volumes and to test the Lifeline system’s capacity. Reports estimate that call volume increased by 45% during the week of transition; encouragingly, this increase was adequately handled by the network (

13). Sustained funding will be necessary to maintain capacity, bring additional centers into the network, and add staffing to existing centers. Continued monitoring of MRRs and CRRs may also inform decisions on which states to prioritize for additional support. For example, additional resources could be directed to states in which the gap between MRR and CRR has widened over time (e.g., Alabama, Montana, and New Hampshire), suggesting growing underutilization of the Lifeline.

This study has several limitations. The precise geographic location of callers was not available, and our use of the telephone area code as a proxy for caller location did not account for mobile phone area codes that may have been different from callers’ county of residence. This occurrence is more common among younger individuals, because they are less likely to own landlines and are more likely to move away from their home county for school or work. Within-state movement, however, should not have affected the results because call volumes were aggregated by state. Information on the specific crisis center answering a call (in-state vs. backup), if available, may provide an alternative way to determine origin county.

Callers to the Lifeline self-identifying as veterans are routed to call centers that are part of the Veterans Crisis Line and staffed by responders specifically trained in military culture. Such calls were not included in this analysis. Given the increasing rate of veterans’ suicide relative to that of the general population and their heterogeneous geographic distribution in the United States, exclusion of such calls has likely differentially affected CRR estimates. Similarly, in addition to telephone services, the Lifeline supports chat and text services, and a more comprehensive assessment of need for crisis services should include chat and text volumes.

Additional data on the proportion of all crisis calls that are handled by call centers that are not part of the Lifeline network, as well as the variance in this proportion by state and over the study period, are necessary to understand the representativeness of the Lifeline data set used here. Similarly, callers to the Lifeline can include those in nonsuicidal crisis, a percentage of callers with potentially considerable geographic dispersion and uneven distribution across study years, rendering a simple aggregation of all calls irrespective of motivation, as used here, a possibly simplistic measure. Other limitations include the unaccounted impact of frequent callers on call volumes (

14), uncertainty in the manner of death certification, and potential undercounting of suicide deaths among people from certain racial-ethnic minority groups (

15).

Conclusions

Utilization of the Lifeline increased nearly fourfold between 2007 and 2020; although a slight decrease in heterogeneity among states was observed, differences in utilization persisted. Analyzing call volumes alongside standardized suicide mortality rates identified specific state groupings, which, in turn, can inform need-based prioritization of outreach efforts for the continued effective utilization of the Lifeline.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Sean Murphy, Ph.D., of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, Vibrant Emotional Health, for providing guidance during data collection and valuable feedback on the manuscript.