In the United States in 2020, more than 1.4 million people were in prisons (

1) and more than 8.5 million spent time in a jail (

2). Approximately two-thirds of all people involved with the criminal legal system have a substance use disorder, and roughly the same proportion have a mental health condition (

3). The rates of substance use disorders and mental health conditions among people who are incarcerated are roughly 10 times higher than the respective rates in the general population (

3–

6). Historical barriers, such as lack of insurance, poor coordination across systems of care, and inadequate capacity in the community behavioral health care system, make accessing community-based treatment difficult for this population. Approximately 80% of people who are incarcerated lack insurance on reentry into their community (

3–

5).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided new opportunities to address low rates of insurance coverage among people with recent criminal legal interactions. In 2014, the ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility criteria to include all adults residing in the community with incomes less than 138% of the federal poverty level. By May 2023, 40 states and Washington, D.C., had expanded their Medicaid eligibility criteria via the framework and funding provided by the ACA. In 2014, the ACA also required guaranteed issue among private health insurance plans (i.e., insurers can no longer deny or exclude coverage because of preexisting conditions) and provided tax credits to low- and middle-income adults to reduce premiums and out-of-pocket costs for private health insurance. Approximately half of all people leaving prisons or jails were expected to be newly eligible for health insurance, either through expanded Medicaid eligibility or subsidized private plans (

3).

Although prior research (

6–

9) has suggested that the ACA is associated with higher rates of insurance for previously incarcerated people, few studies have compared changes in insurance coverage and behavioral health treatment use among people with criminal legal involvement versus among those without such involvement (

7). Prior to the ACA, people with criminal legal involvement had much lower rates of insurance coverage than similar people without such involvement (

3). Given the barriers faced by people reentering the community, the relative gains in insurance coverage and access to care made possible by the ACA may be smaller among people with criminal legal involvement. For example, previously incarcerated adults accounted for more than one-third of the population who remained uninsured 2 years after the ACA’s coverage expansions took effect (

10), suggesting that the disparities in insurance coverage and care that existed before the ACA persist.

Thus, research on the ACA’s effects on disparities in insurance coverage and access to care among people with (vs. without) criminal legal involvement is needed to understand whether disparities remain and need to be addressed in other ways. In this study, we analyzed the combined effect of the ACA’s coverage expansion provisions on rates of insurance coverage and use of treatment services for mental and substance use disorders, from 2014 (when the provisions were implemented) through 2019, among adults experiencing a mental health condition or substance use disorder and having or not having past-year criminal legal involvement.

Methods

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is a cross-sectional and nationally representative survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population older than age 12. Respondents are sampled at the household level by using an address-based sampling frame that includes people living in shelters or group homes but not people who are incarcerated, institutionalized, or without a fixed address (i.e., people experiencing homelessness). The NSDUH uses computer-assisted interviewing and asks respondents about recent and past substance use, psychiatric diagnoses, access to and receipt of treatment services, and previous interactions with the criminal legal system. The survey’s weighted response rate varied from 65% to 70% during our study period (2010–2019).

We restricted our sample to respondents ages 18–64, the target population of the ACA’s insurance coverage expansions, who self-identified as having a past-year mental or substance use disorder via the NSDUH’s validated instruments. These instruments are consistent with definitions of mental illness and substance abuse or dependence from DSM-IV. We included any mental health condition and any substance use disorder (alcohol, cannabis, heroin, cocaine, prescription pain relievers, stimulants, sedatives, hallucinogens, and tranquilizers) included in the NSDUH. Our exposure of interest was whether a respondent had recent contact with the criminal legal system—we included people who reported being arrested and charged with a crime as well as people under community supervision (i.e., on probation or parole) (N=103,818). Our outcomes of interest included whether the respondent had health insurance coverage and had received treatment for a mental health condition or for a substance use disorder in the prior 12 months.

We conducted survey-weighted difference-in-differences (DID) models to quantify whether past-year contact with the criminal legal system was associated with changes in the probability of having health insurance or receiving mental or substance use disorder treatment relative to those without past-year contact. Results are reported as weighted percentages that were derived by multiplying the proportional means by 100. Regression analyses used linear probability models and adjusted for respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex). We also made adjustments for race-ethnicity because structural racism results in higher rates of criminal legal involvement, lower rates of health insurance coverage, and reduced access to health care services among people in non-White communities (

11–

13).

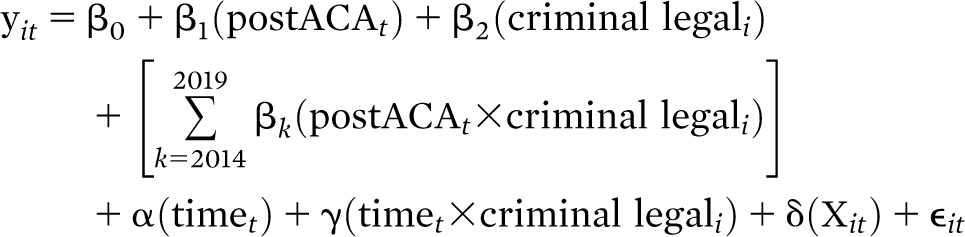

Our regression models included a group-specific linear trend to account for nonparallel growth in the outcome across the two groups, which was evident in event study plots (see Figure S2 in the

online supplement to this report) (

14). This specification requires a fully saturated model with time-varying treatment effects at each postperiod time point (i.e., each year after the implementation of coverage expansions, from 2014 through 2019, represented by postACA

t in the equation):

Where yit is a binary outcome for respondent i at time t, β0 is the preperiod (i.e., the period before ACA’s coverage expansions, from 2010 through 2013) mean of the comparison group, β1 is the postperiod mean of the comparison group, β2 is the preperiod mean of the group with criminal legal system exposure, βk represents the DID estimate in each postperiod year k, α is the preperiod linear time trend for the comparison group, γ is the preperiod linear time trend for the exposure group, δ is a vector of coefficients for respondent characteristics (e.g., age, sex), and ϵit represents the error term. We then averaged the βk for each outcome to construct a single estimate of the treatment effect and used a joint F test to examine whether the linear combination of these coefficients was statistically significantly different from zero.

Because this study used publicly available, deidentified data, it was considered exempt by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. The analysis was conducted, from October 2020 through January 2022, by using Stata, version 14.

Results

Roughly 10% (N=10,539 of 103,818) of the respondents with a mental health condition or substance use disorder had a past-year interaction with the criminal legal system. Prior to the ACA’s insurance coverage expansions, respondents with recent criminal legal involvement were younger; were more likely to be male, Black, and unemployed; had lower rates of educational attainment and mental health conditions; and experienced higher rates of substance use disorder compared with those with no past-year criminal legal involvement (data not shown). Prior to the ACA’s coverage expansions, respondents with a past-year criminal legal interaction had lower rates of health insurance coverage (61.5% vs. 79.3%) and receipt of any treatment for a mental health condition (34.7% vs. 36.3%) but higher rates of substance use disorder treatment (26.0% vs. 3.3%) compared with their counterparts without a recent criminal legal interaction (

Table 1).

After implementation of ACA’s expanded insurance coverage in 2014, the rate of insurance coverage among those with past-year criminal legal involvement and those without such involvement increased to 73.2% and 87.5%, respectively (

Table 1). This result represented an unadjusted increase of 11.7 percentage points in the exposure group and of 8.2 percentage points in the comparison group. The rates of receipt of mental health treatment increased slightly in the exposure (35.9%, an increase of 1.2 percentage points) and comparison (38.3%, an increase of 2.0 percentage points) groups after ACA’s insurance coverage expansions. The comparison group experienced no unadjusted change in receipt of treatment for substance use disorder (3.3%), and the exposure group experienced a 1.7–percentage point increase (27.7%) in receipt of treatment for substance use disorder.

In our adjusted DID analyses, we found an increase in the probability of having insurance coverage in the exposure group relative to the comparison group (4.9 percentage points, p<0.01). However, we found no statistically significant change in the likelihood of receiving treatment for a mental health condition or substance use disorder among adults with past-year criminal legal involvement relative to adults with no such involvement (

Table 1; see the

online supplement for the full regression output). We also found no changes in the specific forms of mental health treatment examined (inpatient, outpatient, or prescription drug) between the exposure and comparison groups (results not shown).

Discussion

Among a nationally representative sample of adults with a self-identified mental health condition or substance use disorder, we estimated the rates of exposure to the criminal legal system, insurance coverage, and receipt of treatment for mental and substance use disorders. For the period before the ACA’s implementation of coverage expansions in 2014, we found a disparity in the rate of insurance coverage among respondents with past-year criminal legal exposure versus those without such exposure. We found that ACA’s expanded insurance coverage provisions led to increases in insurance coverage in both the exposure and comparison groups. Furthermore, the ACA’s expanded coverage provisions reduced the disparity in insurance coverage between these two groups by almost 5 percentage points. However, respondents with past-year criminal legal involvement remained more likely (by 14.3 percentage points) to be uninsured 5 years after ACA’s expanded coverage provisions than their counterparts without a past-year criminal legal interaction. The ACA’s expanded coverage provisions alone were not enough to close the gap in health care access for this vulnerable population.

We also found preexpansion inequities in receipt of mental health treatment between the exposure and comparison groups, and these inequities did not narrow after ACA’s expanded coverage provisions were implemented, a finding consistent with other work (

7). Taken together, these results suggest that interactions with the criminal legal system continue to pose a barrier to obtaining health insurance and mental health treatment. Conversely, our results suggest that adults with criminal legal involvement received substance use disorder treatment at significantly higher rates than did their noninvolved counterparts prior to the ACA’s expanded coverage provisions, although we did not find any change in the rate of substance use disorder treatment after ACA coverage expansions. The greater rate of receipt of treatment for substance use disorder among respondents with a past-year criminal legal interaction was likely the result of the criminalization of substance use.

As with any quasi-experimental analysis, our study had some limitations. Our analysis relied on the counterfactual assumption that differences in outcomes between the exposure and comparison groups would have continued into the postexpansion period in the absence of the ACA’s expanded coverage provisions. This assumption is not observable or directly testable. However, we indirectly assessed the plausibility of these assumptions by comparing estimates across DID regression specifications, including one with group-specific linear time trends.

Although we narrowed our sample to respondents who self-identified as having a mental health condition or a substance use disorder, we could not account for illness severity among respondents, which may have varied by exposure to the criminal legal system. Similarly, we could not account for differences in treatment received, including its intensity, appropriateness, or quality. Finally, we did not have data on factors that might have affected involvement in the criminal legal system, insurance coverage, and health care utilization. These factors, such as diversion and reentry programs, may have differed substantially across jurisdictions, resulting in varying outcomes (

15).

Despite rhetoric urging reform of the fragmented behavioral health system, policy has tended to rely on the criminal legal system to provide treatment and public health–oriented interventions, as evidenced by a 30-year proliferation of treatment courts. Substance use disorder treatment in alternative courts, jails, and prisons often does not incorporate the evidence base (e.g., medications for opioid use disorder) (

16), nor do these settings frequently connect people to high-quality treatment in the community.

People who are incarcerated or under community supervision not only have higher rates of mental health conditions and substance use disorders than the general population but also experience reduced access to care. In the absence of wide-scale reform to the U.S. criminal legal system, potential remedies to address these persistent gaps in health insurance coverage and mental health treatment include the federal Medicaid Reentry Act of 2021, which would require states to provide 30 days of Medicaid coverage prior to release from incarceration, and state action via section 1115 waivers. California’s waiver to provide 30 days of Medicaid coverage prior to reentry was approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in January 2023. Although the current forms of the Medicaid Reentry Act and these waivers represent an important step, they should be amended to include automatic enrollment into Medicaid coverage for 1 year after reentry for anyone reentering the community from jail or prison. State-level opposition to this new provision could be overcome by setting the federal match rate to 100%—the same rate that was used during the early years (2014–2016) of the ACA’s coverage expansions.

Conclusions

Our work demonstrated that people with criminal legal involvement experienced substantial barriers to accessing mental health services. Policy should promote public health–oriented approaches to mental health treatment—such as further expanding health insurance, especially in non–Medicaid expansion states; reducing the administrative burden of health insurance enrollment and of accessing care; and redirecting funding from the criminal legal system to robust, high-quality, community-based outpatient treatment options.