Uptake of virtual care has accelerated exponentially during the COVID-19 pandemic (

1,

2). In addition to virtual provision of outpatient services, virtual wards have proliferated that leverage technology and clinical staff and systems to replicate a hospital ward without a physical location (

3,

4). A virtual ward or “hospital-at-home” can be structured either as early supported discharge, where the goal is to reduce the length of hospital stay, or as admission avoidance, providing an alternative to hospitalization, with admission avoidance showing greater benefits for patients and the health care system than does the early supported discharge model (

3,

5).

Individuals experiencing a mental health crisis are candidates for virtual intervention to avoid hospitalization and to overcome access barriers that can lead to reliance on emergency services (

6). This is a high-risk population, however, for whom care is typically delivered in person through emergency departments (EDs) and hospitals (

7), and literature on virtual care of persons experiencing a mental health crisis is lacking (

8). Examples of pandemic-responsive virtual services for persons with higher-acuity mental health needs have been described, including services for triage and referral (

9) and partial hospitalization (

10). Although beneficial, these programs have a limited role in the acute management of psychiatric emergencies; many of these individuals have psychosis, mania, and suicidal behavior (

11).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, our mental health crisis center in Winnipeg, Canada, opened a virtual acute psychiatric ward (vWARD) to divert hospital admissions (

12). The vWARD provided high-intensity psychiatric monitoring and intervention delivered remotely to individuals in their own environments, with rapid connections to outpatient services or transition to hospital admission when required. This study’s objectives were to assess characteristics of patients admitted to the vWARD, patient-level predictors of transfer to a hospital, acute care use in the 30 days postdischarge, and vWARD cost-saving potential compared with usual care.

Methods

Design and Setting

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in adherence with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (

13). Data were collected for all vWARD admissions from its launch on March 23, 2020, until April 30, 2021, to evaluate patient characteristics and outcomes. The vWARD opened in response to the reallocation of the short-stay in-person ward to serve COVID-19–positive patients. It was based at the Crisis Response Centre (CRC) in downtown Winnipeg, a mental health–specific 24/7 walk-in center for individuals ages ≥18 years. The vWARD was designed as a rapid assessment and intervention service for patients who met criteria for voluntary hospital admission. Care was delivered virtually, with multiple contacts a day as required. The vWARD team consisted of six physician assistants and three psychiatrists, who rotated on services providing diagnostic assessment, medication management, risk management, supportive care, and psychoeducation. Patients also had access to 24-hour crisis support available in person at the CRC and through the telephone crisis line staffed by trained mental health clinicians. The target length of a vWARD stay was 3 days, which could be extended according to a patient’s needs. If the individual’s condition could not be managed in the community, hospital admission was coordinated, often directly from the individual’s home to the inpatient unit. Specific service components of the vWARD are described in

Box 1.

This study was approved by the University of Manitoba Research Ethics Board (HS23878 [H2020:196]). Because the study consisted of a retrospective review of patient data, informed consent was not required.

Participants

Admissions to the vWARD came from the CRC and two EDs in two academic hospitals. Individuals were eligible for referral if they met criteria for a voluntary hospital admission, agreed to virtual care, and had access to the necessary technology (ideally a device supporting videoconferencing, but a telephone was also acceptable). There were no restrictions on diagnosis or concomitant care, as long as the vWARD referral was complementary and not redundant to other services accessed. Risk for harm to self and others was fully assessed before referral, and a safety plan was completed if indicated.

Data Sources

The vWARD team completed a discharge form for all admissions. The form captured patient demographic and clinical characteristics and service delivery and outcome variables. A retrospective chart review of electronic patient records (EPRs) was completed to retrieve additional vWARD data documented during the stay, as well as preadmission (6 months before admission) and 30-day postdischarge health care utilization data. Two EPRs were reviewed: the CRC record to capture data on all CRC visits and vWARD stays and the provincial EPR to capture data on all ED visits and inpatient admissions at major centers in the province. Data from all sources were linked by using the individual’s provincial personal health information number. The first three digits of postal codes were collected to determine median household income on the basis of data from the Statistics Canada 2016 Census profile (

14).

Variables

COVID-19 timeline.

Each admission was coded according to Winnipeg COVID-19 lockdown status (based on heightened public health restrictions). The periods were as follows: lockdown 1, study launch to May 3, 2020; between lockdowns 1 and 2, May 4 to September 27, 2020; lockdown 2, September 28, 2020, to February 12, 2021; and after lockdown 2 to the end of the study period, February 13 to April 30, 2021.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Age, gender (female, male, or other), and living situation during admission (alone or with others) were collected. Neighborhood income quintiles were created for the sample, with Q1 representing the lowest income quintile.

Clinical characteristics.

Main presenting problems at referral were coded in non–mutually exclusive categories: depression, anxiety, psychosis, mania, suicidal or self-harm, personality disorder, or other. To capture conditions that typically represent more acute presentations that may be challenging to manage virtually, we grouped mania with psychosis and coded it as present or absent. The presence of suicidal behavior at the time of referral was coded as the highest level: none, ideation, planning, or attempt. Active substance use at the time of referral was coded as present or absent, with present referring to problematic substance use regardless of whether a substance use disorder diagnosis was made. Previous 6-month utilization of acute care services included any use and number of visits for any reason and presence of psychiatric hospitalizations specifically.

Service delivery.

Service delivery variables included length of stay in the vWARD, number of psychiatry assessments in the vWARD, type of contact with the vWARD team (telephone exclusively or some combination of telephone and videoconferencing), and whether any call was made to the crisis line. We also collected data on any virtual involvement of family members or other supports, defined as participation in one or more psychiatric assessments. To involve family, informed consent was obtained from the patient. Family and other supports often played a key part in at-home observation and medication assistance.

Outcomes.

Disposition from the vWARD was transfer to a hospital or discharge, which could include referral to outpatient services or connection with preexisting providers. For individuals who were not transferred directly to a hospital from the vWARD, we captured 30-day postdischarge outcomes as occurring or not in three nested levels of increasing specificity: any-cause acute care visit, any specific mental health acute care visit (ED, urgent care, CRC, or hospitalization), and any psychiatric hospitalization.

Costs.

To calculate costs of usual care, we assumed that all vWARD admissions would have been hospitalizations had the program not existed. The vWARD discharge diagnosis was categorized by using the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) diagnostic case-mix groups by age group (18–59, 60–79, and ≥80 years) (

15). CIHI collects and standardizes inpatient data from jurisdictions across Canada and has developed the Patient Cost Estimator, which maps the discharge diagnosis onto the expected costs (in Canadian dollars [CAD]) of a hospitalization. These data are based on several years of acute care inpatient activity and cost records (

15). The Manitoba-specific cost estimates for each diagnosis were used in these analyses. The most recent available costs were in 2018 CAD, and they were adjusted into 2021 CAD by using a rate of 1.0617 obtained from an inflation calculator (

https://www.inflationtool.com/canadian-dollar?amount=100&year1=2018&year2=2021&frequency=yearly).

To approximate program costs, we used conservative assumptions. We assumed that a full-time team with daily resources totaling 4 hours of psychiatrist time, 8 hours of physician assistant time, and 8 hours of clinician time could support eight to 10 individuals in the vWARD. Because the program operated with redeployed resources and capacity was limited to three or four admitted individuals, we took 50% of the cost of the full-time team, in addition to an operating budget ($60,000) and 4 hours weekly of directorship time. We also added the actual costs for all hospital days incurred by individuals who were admitted to the hospital directly from the vWARD.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for the sample of vWARD admissions, stratified by the outcome of hospitalization or discharge. A logistic regression was used to examine predictors of hospitalization. Independent variables included pandemic timeline, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics. Previous 6-month psychiatric hospitalization was included, given its strong association with subsequent hospitalization (

16). Cumulative survival for each 30-day postdischarge outcome was plotted as a Kaplan-Meier curve.

An analytical technique known as a break-even analysis was conducted to determine the circumstances under which the costs of the new intervention would be lower than the costs of usual care. When this occurs, the new intervention is relatively cost saving. A finding that usual care assumptions are consistent with input values in the cost-saving region on a break-even plot provides evidence that the intervention is cost saving. If modifying a usual care assumption changes the result in terms of which option is less costly, the change is evidence that the findings are sensitive to the assumptions. High and low values for the usual care costs were set to illustrate the results. All referrals to the vWARD clinically warranted hospitalization, but not all referred patients would have necessarily been hospitalized if the program did not exist, and we therefore examined to what extent usual care costs could be lower and the program would still be cost saving. All analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel; SPSS, version 28; and Stata, version 17.

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, there were 132 admissions of 130 unique patients to the vWARD. The mean±SD length of stay was 2.4±1.2 days (range 1–8 days), with 2.3±1.2 psychiatric assessments per stay. Care delivery was exclusively by telephone for 56 admissions (42%), and a combination of telephone and videoconferencing for the other admissions. More than one-third of the admissions had virtual involvement of family members or other supports (N=50, 38%). Crisis calls occurred in 22 (17%) admissions.

Table 1 presents data for the vWARD admissions. Admissions occurred across the COVID-19 timeline, with the highest proportion between lockdowns 1 and 2 (42%). The mean age of vWARD patients was 34.5 years. The proportion of females (57%) was slightly larger than the proportion of males. During admission, most patients lived or stayed with other people, such as family, partners, or friends (76%).

More than half the admissions involved a patient with suicidal behavior (N=75, 57%). Psychosis or mania was present in 29% and active substance use in 33% of the admissions. Other presenting problems included depression (N=42, 32%), anxiety (N=23, 17%), and personality disorder (N=18, 14%). Overall, 14% of admissions were preceded by a psychiatric hospitalization in the past 6 months. For an additional 58 admissions (44%), the individual had an acute care visit in the past 6 months that did not result in hospitalization, with visit counts ranging from 1 to 16.

Outcomes

Hospitalization.

In total, 17 admissions (13%) resulted in transfer to a hospital from the vWARD. In the adjusted logistic regression (

Table 2), only the presence of psychosis or mania (vs. its absence) was significantly associated with transfer (OR=34.2, p=0.003).

Use of acute care within 30 days.

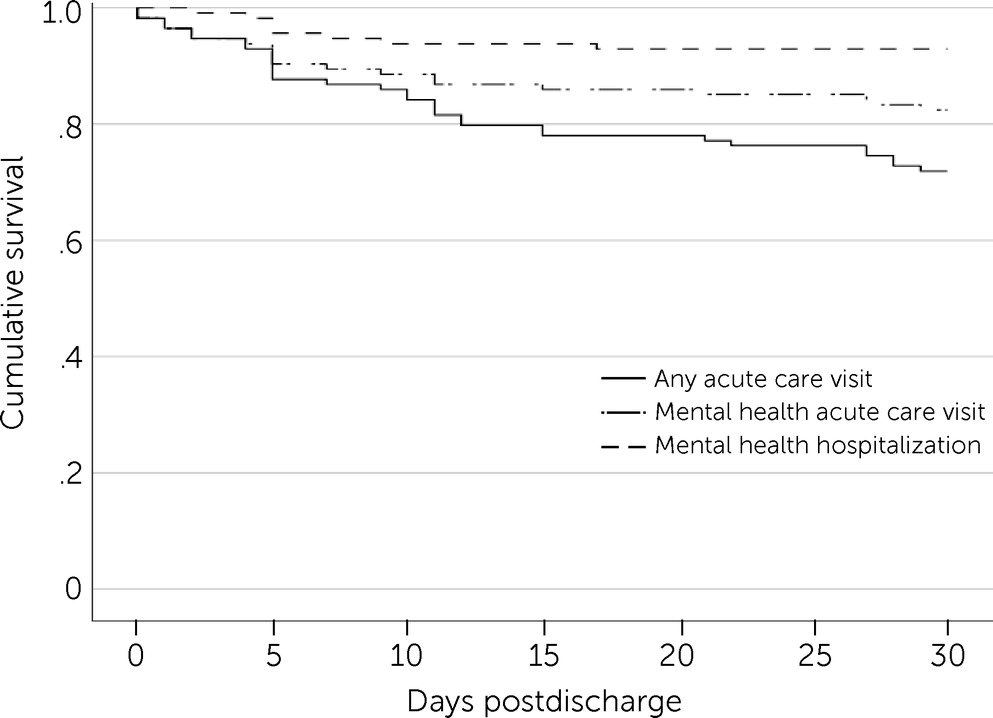

The Kaplan-Meier curve for each outcome of acute care use in the 30 days after vWARD discharge is shown in

Figure 1. Complete data were available for all but one admission for which postdischarge data were not available. Thirty-two of 114 individuals had any acute care visit (cumulative survival±SE=0.72±0.04). The visit was a mental health–specific visit in 20 of the 114 cases (cumulative survival±SE=0.82±0.04). Of those, eight visits were mental health hospitalizations (cumulative survival±SE=0.93±0.02). Overall mean survival time for any-cause acute care visit was 26.5 days (95% CI=25.6–27.4). In the first 5 days postdischarge, most outcomes were related to mental health, with increasing visits for other reasons over the remainder of the follow-up period. Nearly all psychiatric hospitalizations occurred in the first 10 days postdischarge.

Economic Analysis

A table presenting data on admissions to the vWARD by CIHI diagnostic category, with the corresponding costs of hospitalization (converted to 2021 CAD), is included in the online supplement to this article. The table also presents data on the number ultimately admitted to a hospital and total days in hospital. The program costs, after inclusion of the operations costs ($320,627) and the costs for individuals who were transferred to a hospital directly from the vWARD or who were hospitalized within 30 days postdischarge ($132,843), totaled $453,470. The total estimated usual care cost was $1,043,394. The high and low cases for usual care cost assumptions were set at $1,327,125 and $796,275, respectively. On the basis of the data and assumptions, the results of this economic analysis indicate that the costs of the virtual program would be more than offset by the cost savings, compared with costs of usual care.

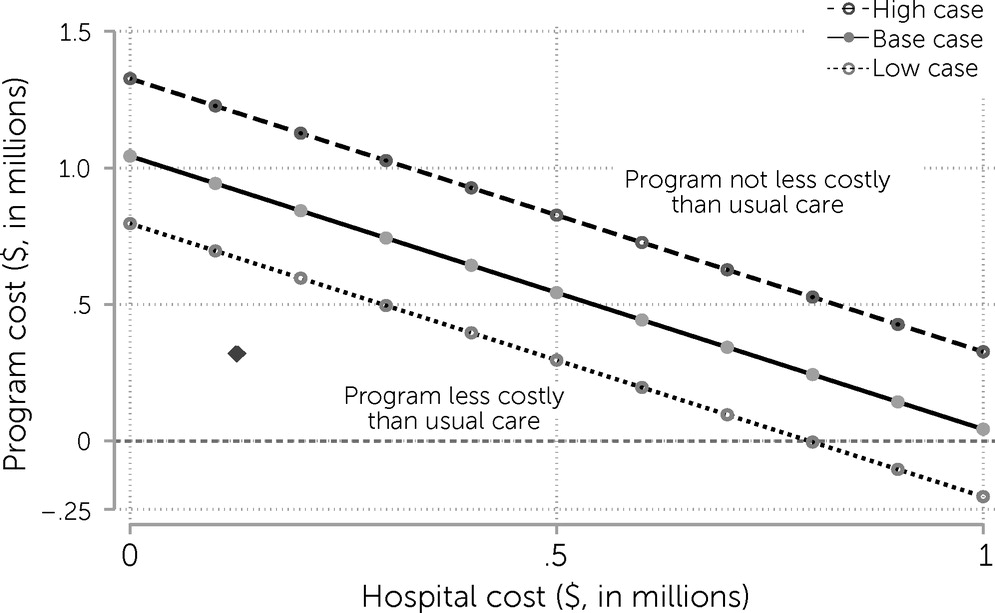

We conducted a break-even analysis to determine the effect of varying estimates (

Figure 2). The diamond in

Figure 2 indicates the observed program costs on the y-axis ($320,627) and the hospital costs for patients who were directly transferred to a hospital on the x-axis ($132,843). The diamond is below all the estimates represented by the lines, indicating that even if the total cost of usual care was lower than was estimated, the vWARD costs would still be lower. In fact, the cost estimates for usual care could be >50% lower than those assumed in the base case, and the virtual program would still break even (i.e., 50%×$1,043,394=$521,697>$320,627+$132,843=$453,470).

In a best-case scenario, where hospital costs for individuals admitted to the vWARD are $0 (i.e., all transfers to a hospital directly from the vWARD are avoided), the program costs could double and the program would still be cost-effective, compared with the estimate for usual care. In contrast, if every admission to the vWARD were transferred to a hospital, the program cost savings would not cover the program’s operating expenses. However, if the program reduced usual care costs by half (i.e., by reducing hospital days), it would be cost neutral. Our usual care values indicate that the vWARD is likely less costly than usual care in many circumstances, even with additional costs that are not accounted for in these program cost estimates.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred innovation in health care delivery. In-person at-home crisis stabilization services have previously been established to divert individuals from hospitalization and from use of EDs (

17), and the evaluation of our vWARD supports the feasibility and cost-savings potential of a completely virtual at-home model that avoids hospital admissions. The vWARD patients were diverse in mental health needs and sociodemographic characteristics. More than half of admissions involved suicidality, and nearly a third had psychosis or mania. Although a portion of vWARD admissions resulted in transfer to a hospital, 30-day postdischarge outcomes were favorable, and the program appears to have saved costs according to a variety of scenarios.

The presence of psychosis or mania was the only significant predictor of transfer from the vWARD to a hospital. This outcome was somewhat expected, given the clinical features of persons with these conditions: disorganized behavior, hallucinations, delusions, loss of insight, and impulsivity. Such presentations often require a controlled, low-stimulus environment to stabilize the patient (

18). Transfer to a hospital also ensures adherence to pharmacotherapy and abstinence from substance use. However, only one-third of individuals with psychosis or mania were transferred from the vWARD to a hospital; often these individuals were admitted to the vWARD because they initially declined hospital admission and did not meet criteria for involuntary admission. The vWARD may function as transitional support to provide education for patients and close contacts, initiate treatment, monitor progress, and assess the need for in-hospital care. Treatment on the vWARD may be particularly appealing for first presentations, where stigma and fear may delay care and lead to worse outcomes (

19). The rate of psychiatric hospitalization in the 30 days postdischarge was favorable, compared with readmission rates in Canada (which had a risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rate of 13% in 2019 [

20]). The occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization shortly after discharge may indicate that a longer stay could avoid additional admissions.

The vWARD enabled cost savings, compared with usual care, across a range of scenarios. Mental disorders contribute to some of the highest health care expenditures, and programs that can help reduce such costs are urgently needed (

21). In addition to the high costs of inpatient care, many patients dislike the inpatient setting (

22). Admission avoidance models that integrate with outpatient services can function as an effective alternative to hospitalization. Findings from an analysis of the crisis resolution team model, developed to reduce and gatekeep hospitalization by offering 24-hour access to intensive support through home visits, supported the delivery of high-intensity community-based crisis care and suggested a potential for improved outcomes (

17). The vWARD leverages technology that may further optimize resources and flexibility for patients and families. Our vWARD is run by a medical team with physician oversight, addressing one of the limitations noted for models in which the virtual setting is entirely staffed by other professionals (

17). To add in-person outreach and other team members to our vWARD team would require more resources, but such additional staff may optimize use of medical staff and facilitate treatment of individuals whose presentations may be challenging for exclusive virtual assessment.

This study had some limitations. The vWARD was rapidly implemented at the start of the pandemic by using redeployed rotating staff. The team members changed often, which could have resulted in varying thresholds for length of stay. The focus of the model on reassessment and brief stay may have led to early discharge for some individuals who could have benefited from a longer stay. The vWARD was integrated within a 24/7 crisis center supporting after-hours care options; although not essential, this was an important program component. Costs were estimated on the basis of the assumption that vWARD admissions would otherwise have warranted hospitalization and that length of hospitalization would approach the average. Although a criterion for referral to the vWARD was a clinical presentation warranting hospitalization, vWARD admissions overall may have been less acute than hospital admissions, given that a requirement for vWARD admission was that it was safe for the patient to be in the community. The approach to costing used a conservative estimate of program costs and a break-even analysis to account for some of the limitations imposed by the assumptions and available data. We did not have data on how many individuals were offered the vWARD and how many declined, and these data may have been subject to variation related to COVID-19 risk. In future studies, it will be important to assess the rate of suitability and acceptability of the model in a steadier state of external influences.