At least 10 years of life are estimated to be lost for individuals with psychotic, affective, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

1). A similar mortality gap has been found between individuals with eating, neurocognitive, neurodevelopmental, and personality disorders and those in the general population (

2). Moreover, each additional comorbid psychiatric condition an individual experiences is estimated to widen this mortality gap by over 2 additional life-years lost (

2). Coordinated health care could help close the mortality gap by meeting the needs of patients with complex conditions. However, this potential has not been studied in psychiatric care settings (

3,

4).

One promising evidence-based model for delivering coordinated care is the collaborative chronic care model (CCM), which delivers anticipatory, interdisciplinary, and patient-centered health care in team-based settings (

5). CCM involves realigning work roles and organizational leadership, linking services with community resources, and managing information to support patients’ self-management and improve clinicians’ decisions (

6). An essential advantage of CCM is adaptability, because components can be tailored to meet local needs and goals. Although randomized controlled trials outside mental health care settings have shown that CCM is associated with reduced mortality (

7,

8), all have excluded patients with serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia (

3,

4). In addition, research has indicated that increased depression symptom severity may be associated with significant reductions in mortality after intervention (

9).

The current study examined the CCM’s effectiveness in mitigating mortality risk by using data from a randomized implementation trial conducted in general mental health clinics at nine U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. VA’s national network of general mental health clinics serves adult veteran populations with high rates of psychiatric disorders and complex comorbid conditions. Therefore, VA is an ideal setting to study the CCM’s impact on mortality, with results also applicable to other adult populations with similar complex conditions.

Methods

The VA Central Institutional Review Board approved this study as a combined quality improvement program evaluation and research project. Full details on the trial’s recruitment, enrollment, and design (

7,

8) and the distribution of individual- and site-level characteristics across arms have been published (

10). As a brief overview, recruiters identified 11 interested VA medical centers. The first nine sites to respond were enrolled. The intervention group consisted of 5,570 patients treated in the general mental health clinics that participated in the CCM implementation support trial (

11). The control group included 46,443 patients treated in non-CCM general mental health clinics at the same VA medical centers as CCM clinics, such that every center had both CCM and control clinics. Quality indicator data were available at the level of the VA medical center and could not be compared between clinics at the same center. No patients treated in either CCM or control clinics were excluded from this study or from analysis, except those with dementia. Patients were followed up for 1 year. The nine VA medical centers were randomized under a stepped-wedge design into three groups, each consisting of three sites. Groups’ implementation start times were staggered by approximately 4 months, with the first group of sites starting implementation in February 2016 and the last group of sites starting in February 2017. Patients in the CCM clinics were compared with those in control clinics contemporaneously. We used electronic health record data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse to construct time-to-event data on the basis of study protocol time, allowing group aggregation regardless of groups’ calendar start time.

Mortality data were captured from VA’s Master Veteran Index (MVI), which uses data from the National Cemetery Administration, Social Security Administration Death Master File, and VA’s Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture. Agreement rates between death dates found in the MVI and the VA Vital Status File (VSF) are >99%. The MVI is the authoritative source of mortality data for VHA operations (

12).

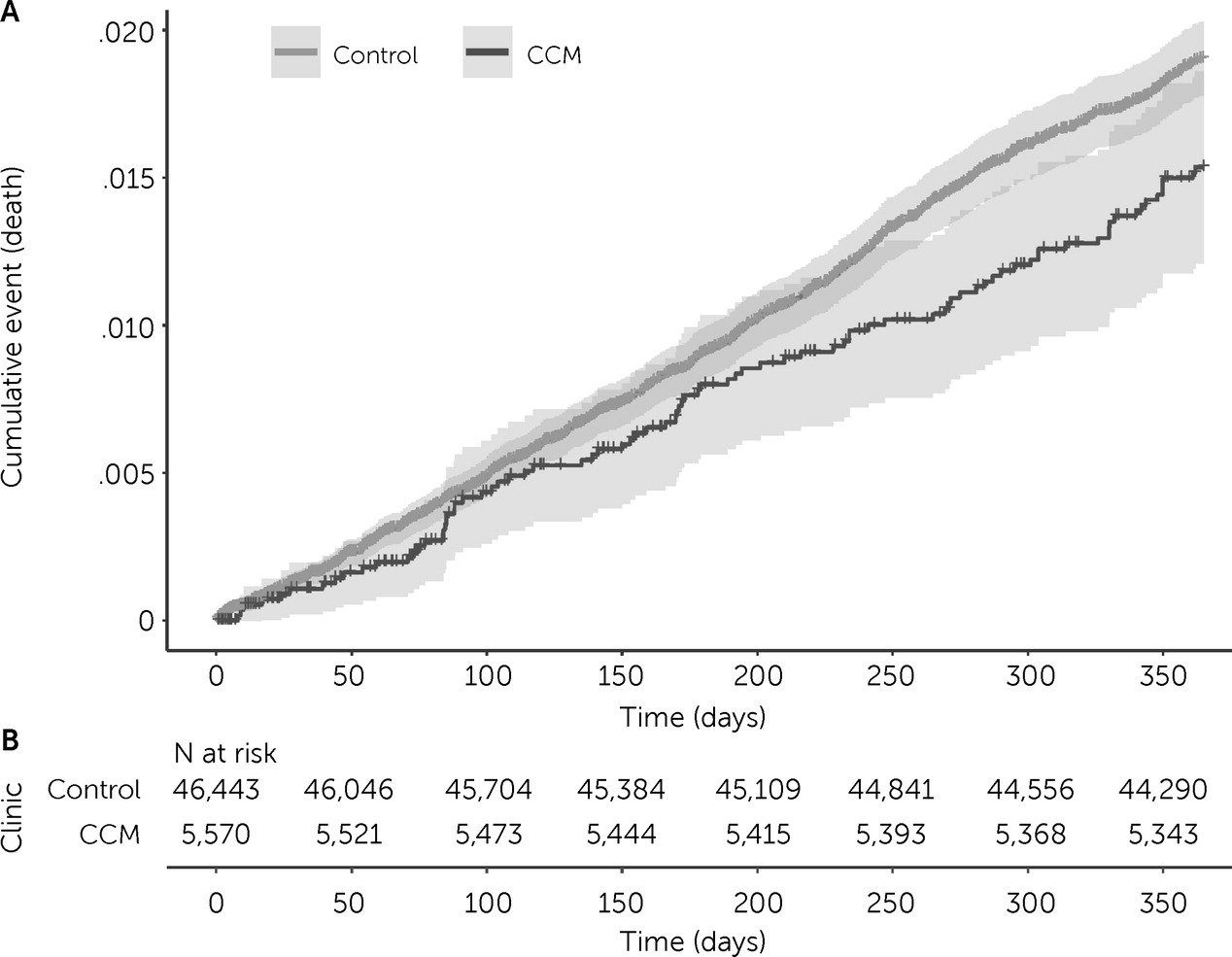

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves were visualized by using the R survminer software package, version 0.4.9 (

13). We estimated the hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality among patients in the CCM cohort, compared with those in the control cohort, with a Cox proportional hazards model by using the R survival software package, version 3.2-13 (

14). Our multilevel model was conditioned on a multinomial variable for the center where patients’ clinics were located (capturing CCM fidelity, as operationalized in the primary implementation trial) (

11) and on individual-level variables capturing baseline acute care utilization, including history of one or more general medical or psychiatric hospitalizations in the year prior to CCM implementation. Schoenfeld residuals were used to check the proportional hazards assumption. Unmeasured residual confounding was estimated by calculating the E-value.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine CCM’s effect on all-cause mortality when delivered in a mental health setting. When the analysis was adjusted for site-level factors, the CCM clinics were associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality, compared with care at control clinics within the same VA center that did not implement the CCM (HR=0.76). For comparison, a prior CCM trial conducted in a primary care setting reported a reduction in mortality over almost 4.5 years among individuals in the CCM group, relative to control participants, that was greatest among those with major depression (

9). However, most excess deaths in that study were due to cancer. Our findings suggest a more wide-ranging effect of the CCM on mortality in a diagnostically diverse cohort of individuals with various levels of psychiatric syndrome severity. Thus, our results suggest that the CCM can reduce all-cause mortality for a broader group of psychiatric patients than previously demonstrated.

One explanation for our findings might be that the CCM enhances detection of clinically significant acuity of illness. Core components of CCM support this possibility in that they increase the frequency and variety of contacts across specialties between patients and clinical staff (

7–

9). For example, outreach managers may help patients miss fewer appointments and specialist consultations, providing more opportunities for self-disclosures. In addition, the interdisciplinary nature of CCM teams can help clinicians identify a wider range of indicated interventions and enhance communication between otherwise siloed providers and support staff. Moreover, increased detection of illness acuity could lead to more targeted use of lifesaving interventions. Prior analyses of our trial could be consistent with this reasoning. For example, although the CCM was previously shown to lead to fewer psychiatric hospitalizations overall compared with control clinics (

11), the hospitalizations that occurred were predominantly among individuals with a recent psychiatric inpatient history (

10)—that is, those with higher mortality risk at baseline (

1). Specifically, compared with patients treated in the control clinics, patients treated in the CCM clinics who had higher mortality risk (who were psychiatric inpatients during the pretrial year) were five times more likely to be hospitalized during the trial than patients with lower mortality risk (who were not psychiatric inpatients during the pretrial year) (

10). If the CCM increases detection of illness acuity, which leads to more selective psychiatric hospitalizations, then the model could save lives while decreasing the number of unnecessary hospitalizations.

Our study is also the first to examine the effect of the CCM on mortality when delivered in a general mental health care setting. We demonstrated a beneficial effect of the CCM on life expectancy among patients who were not selected for having life-threatening illness through an adequately powered national study in which several regions of the United States were represented. In addition, differences between medical centers were addressed at two levels. At the design level, the CCM and control clinics were paired within the same medical center. At the analysis level, our multilevel model was conditioned on site (capturing the total unspecified fidelity of a site, differences in case mix across sites, and other institutional differences affecting mortality but unrelated to the CCM) and on individual history of prior general medical or psychiatric hospitalization in the preceding year (capturing baseline differences in acute care utilization that might lead to the same patient being hospitalized at one clinic center but not another).

However, because quality indicator data were collected at the level of the VA medical center, a possible limitation is that quality may have differed between the CCM and control clinics, even if they were located at the same center. In addition, our study was not powered to detect subgroup differences in treatment response for clinics within the same medical center. Future studies that compare clinics within the same center may benefit from explicitly accounting for clinic-level quality indicators and subgroups.

Another study limitation was the use of a quasi-experimental, controlled, cluster-randomized design. It is possible that residual confounding due to randomization only at the level of clusters could have introduced bias into our results. However, sensitivity analysis with the E-value demonstrated that for our findings to be explained by a type I error, the combined magnitude of unaccounted confounding in our analysis would have to be HR≥1.99 (E-value=1.98). Because our study was not observational, we interpreted this estimate as the size of bias needed to nullify our results because of confounding not already accounted for by the balancing of individual characteristics after cluster randomization in the study design or by adjustments made for site-level characteristics in the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics from the primary trial suggested that all measured patient characteristics achieved a good balance between the CCM and control clinics, as previously described (

10,

11). Further adjustment for well-balanced individual-level factors did not improve estimate precision, and our results were robust.

The external validity of this study was limited by the sample, which comprised U.S. military veterans and predominantly men. As a result of military service, veterans also have a higher rate of mental health conditions than civilians, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder and general chronic disease. Direct comparison with nonveterans was not possible. However, past CCM trials have also observed reduced mortality among older, nonveteran adults with chronic illness (

7,

8). It is unknown whether the CCM may also benefit other nonveteran populations with similar complex or multiple comorbid conditions.

Although discrepancies in mortality data existed between VA’s MVI and VSF, discordance was less than 1% (

12), a difference that would not change our results. In addition, MVI captures recent deaths better than VSF (

12), thus representing more complete data for our study. MVI also compares favorably to the National Death Index (NDI), which has a sensitivity for capturing deaths approaching 100%. Agreement rates between the MVI and NDI for death dates (±2 days) are close to 99%. Moreover, after a death occurs, a lag of up to 2 years may ensue before the NDI reports the death (

15).