Food insecurity is defined as a household-level socioeconomic condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate amounts of food (

1). Food security is built on three components:

food availability (sufficient quantities of food being consistently available),

food access (sufficient resources to obtain adequate food), and

food use (appropriate intake based on knowledge of nutrition and food preparation). Because food availability is not guaranteed, given potential threats to food resilience caused by climate change–related weather events and temperature changes, water crises, land degradation, overfishing, fuel shortages, shipping disruptions, wars, and other factors, a fourth pillar of food security—beyond availability, access, and use—is

food stability. In the United States, the prevalence of food insecurity in recent years has been 11.1% (2018), 10.5% (2019 and 2020), and 10.2% (2021), meaning that, for example, 33.8 million people were food insecure in 2021 (

2). Rates of food insecurity are higher in households with children, especially those headed by a single parent; households headed by non-Hispanic Black or by Hispanic individuals; and households with incomes below 185% of the federal poverty level ($30,000 for a family of four in 2023) (

2).

Rather than being an issue of food availability (the United States has a sufficient overall supply of food, and food waste is a widely recognized problem), food use, or food stability, U.S. food insecurity is mainly a problem of food access: the available food is unevenly and unfairly distributed. This is especially true of healthy and nutritious food, in keeping with a recent reconceptualization of food security as nutrition security (

3). The unjust distribution of access to healthy food is carved along sociodemographic and geographic lines, as exemplified by the concept of

food deserts, geographic areas (like census tracts) with limited access to affordable and nutritious food and substantial distances between supermarkets.

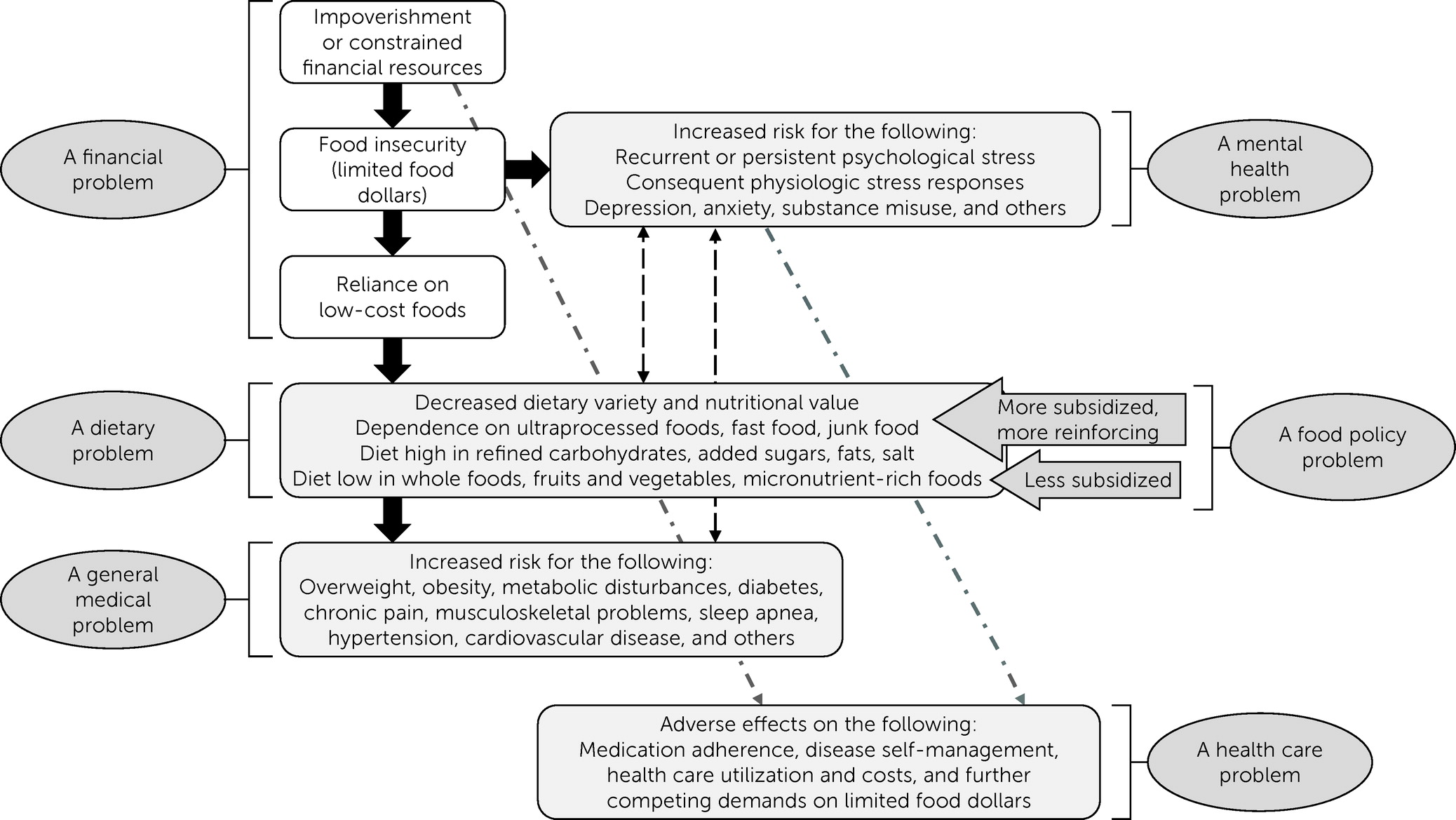

The initial financial problem leads to a series of dietary problems, which then cause overall health problems (worsened by food policy problems) and, ultimately, health care problems;

Figure 1 illustrates the chain reaction. In the United States, policies focus on food and nutrition security rather than on

hunger, which is usually considered to mean having insufficient amounts of food or raw calories to meet basic nutritional needs for sustained periods and being at risk for malnutrition as a result. Hunger and food shortages are ongoing and devastating issues for people in many low-income countries.

Food and Nutrition Insecurity as a Social Determinant of Health

Food and nutrition insecurity has been linked to numerous health conditions (

4). In the United States, food and nutrition insecurity tends to be associated not with underweight and malnutrition but, rather, with overweight and obesity (

5). Having limited food dollars reduces people’s purchasing options and leads them to spend those funds in a way that provides as many calories as possible—often in the form of energy- or calorie-dense foods high in fats and added sugars and low in micronutrients and nutritional value (e.g., fast food, junk food, and other ultraprocessed foods) (

Figure 1).

Beyond its serious effect on general medical health, food and nutrition insecurity has been repeatedly associated with several poor mental health outcomes. Hundreds of studies have documented associations of food and nutrition insecurity with psychological distress, depression, and suicidality, among other poor mental health outcomes, across the life span. Food and nutrition insecurity, similar to other social determinants of mental health, causes repeated instances of acute stress, chronic stress, or both, negatively affecting physiology through an interplay of neural, endocrine, and immune mechanisms (e.g., activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis). Among individuals with mental illnesses, food and nutrition insecurity impedes treatment adherence, disease self-management, and recovery while setting the stage for overweight, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disturbances in addition to issues brought about by psychotropic medications and the chronic stress arising from other social determinants of health (e.g., housing instability, discrimination).

Neglect of Food and Nutrition Insecurity Versus Other Social Determinants

The social determinants of mental health are increasingly recognized as warranting attention in terms of both policy (the public health approach) and clinical care (the biopsychosocial approach). Regarding the latter, mental health professionals contend with multiple social determinants among their clients and communities, including adverse early life experiences, racism and other forms of discrimination, job insecurity, housing instability, and poor access to health care, to name a few (

6). Mental health professionals are accustomed to incorporating many social determinants related to basic needs (e.g., housing, transportation, and access to health care) into psychosocial assessments. Furthermore, additional social determinants—such as criminal legal system involvement (along with its disproportionate effect on communities of color and on individuals with serious mental illnesses, e.g., schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) and air pollution and its culmination in global climate change—are gaining recognition as key drivers of poor mental health. The mental health field is increasing its support of movements that aim to rectify these societal problems. Yet, one could argue that food and nutrition insecurity remains a neglected social determinant. Next, I point out three basic facts that we as mental health professionals should know and three levels at which we can work to address food and nutrition insecurity.

Knowing About Food and Nutrition Insecurity

First, similar to other social determinants, food and nutrition insecurity at both population and individual levels impedes achievement of optimal mental health, increases risk for behavioral disorders, worsens outcomes among those with existing disorders, and creates mental health inequities between population groups. Second, as with any other social adversity, food and nutrition insecurity can be screened for, assessed, evaluated, addressed, and monitored by health professionals, including mental health professionals. Third, the rate of food and nutrition insecurity among individuals with mental illnesses is higher than that of the general population; for those with serious mental illnesses, the rate is alarmingly high (

7,

8).

Regarding the third point, about 70% of individuals with serious mental illnesses in public-sector mental health clinics are food insecure (compared with 10%–11% in the general population), often because they are also contending with unemployment, poverty, and other social disadvantages (

7,

8). Relatedly, those with serious mental illnesses experience disproportionately high rates of overweight, obesity, metabolic disturbances, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic physical diseases that cause early mortality and that can be mitigated in part by better access to nutritious food.

Acting on Food and Nutrition Insecurity

Action is needed at multiple levels. Here, I highlight three of those levels and actions that can be taken at each. First, at the population level, where the goal is primary prevention (i.e., overall health promotion, mental health promotion, disease prevention, and mental and substance use disorder prevention), action is required in terms of both changes to public policies and changes to social norms (

9). The former means that mental health professionals must contribute to conversations and deliberations about federal and state legislation and other policies related to food and nutrition. The predominant federal policies related to food and nutrition are delineated within the U.S. farm bill, an omnibus bill renewed about every 5 years. At the state level, relevant policies direct how the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); school meal programs; and other food and nutrition assistance programs are administered (e.g., SNAP’s statutes, regulations, and waivers provide state agencies with numerous policy options that enable them to adapt their programs substantially) and how such programs are expanded with state dollars. For example, some states offer SNAP-related incentive programs to encourage recipients to make purchases at farmers markets (where fresh, whole produce is sold, as opposed to ultraprocessed foods).

Although federal and state policies play major roles in food and nutrition security and thus mental health, we as mental health professionals must challenge social norms by articulating to the public that food and nutrition insecurity at its current, stable rate (around 10%–11% overall, but with prominent variation across states and subpopulations) is unacceptable. We must make it clear that food and nutrition insecurity is damaging the mental health of many people in the United States and causing mental illnesses (and diseases of despair) and that nutrition is as much a mental health issue as it is a general medical health issue.

Second, action is also needed at the local or community level. Mental health professionals need to advocate for and help to strengthen food banks (regional nonprofit organizations that collect food products from the food industry and food drives; inventory and safely store them; and distribute them to food pantries, soup kitchens, etc.) and food pantries (local sites, such as churches or community centers, where food is directly distributed to local individuals in need). Mental health professionals can also advocate for the provision of medically tailored meals and other “food is medicine” initiatives; programs that provide people with better opportunities to afford and access whole foods and fresh produce; and classes or training resources that give people the knowledge, motivation, and self-efficacy to incorporate healthy food into their daily diet.

Third, although effects may be more incremental for families and individuals, mental health professionals can act at this level through their work in clinical settings or through collaborations with schools, colleges, universities, workplaces, primary care practices, or community-based organizations. In clinical venues, where the social determinant (societal problem) of food and nutrition insecurity manifests as an individual-level social adversity, clinicians can apply their well-established approach to care—that is, screening, assessment, treatment, and follow-up—to food and nutrition insecurity. The first step is screening. More comprehensive food insecurity measures exist, but a two-item food insecurity screener has been validated in primary care settings (

10). Specifically, clinicians can screen for food insecurity by using the following script.

Please tell me whether these statements were often true, sometimes true, or never true for you or your household in the past 12 months. First, “Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.” Second, “Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

A positive screening (a response of “often true” or “sometimes true” to either question) may indicate food insecurity. Suggested follow-up questions have been put forth (

6) for mental health professionals to explore food insecurity, nutrition, and dietary habits among clients.

Possible counterarguments to the suggestion that food insecurity screening should be conducted in behavioral health programs are that clinicians already have limited time with clients, so adding yet another screening measure increases burden without evidence that care will be improved by screening, and that screening should be done only when community resources are available for referrals. Yet, if the two-item screener can be successfully used in primary care settings, then it can also work in behavioral health settings. Given findings that those with serious mental illnesses have very high rates of food and nutrition insecurity and alarming early mortality from conditions driven in part by diet-related conditions, the screener is arguably even more needed in behavioral health than in primary care settings.

The “treatment” of food and nutrition insecurity is improving access to healthy food. Facilitating participation in SNAP and its related nutrition education is one approach. Some clients may also be eligible for other U.S. Department of Agriculture–supported food and nutrition assistance programs (e.g., WIC). Facilitating access to local food support programs (e.g., food pantries) is another approach. Mental health professionals should be familiar with or have a means of easily identifying food pantries in the communities where their clients live and the special state or local programs that support food and nutrition security (e.g., farmers market incentive programs). Follow-up is warranted for clients with food and nutrition insecurity, just as it would be for any other psychiatric or social condition. Screening should be longitudinal, because income, employment-related or public benefits, family relations, criminal legal involvement, and other factors affect a client’s risk for food and nutrition insecurity.

Conclusions

Food and nutrition insecurity is one of many societal problems that impede a population’s achievement of optimal mental health, increase risk for behavioral disorders, worsen outcomes among those with such disorders, and cause mental health inequities. Mental health professionals have a role in addressing food and nutrition insecurity across multiple levels. Knowing about this neglected social determinant of mental health is the first step to taking the necessary and warranted actions to ameliorate it.