The COVID-19 pandemic has called attention to a trend of increasing mental health challenges among U.S. youths, which had already been identified in national surveillance data before 2020 (

1). For example, 2019 data from the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey revealed concerning escalations in indicators of poor mental health among high school students, with 37% of students reporting feelings of persistent sadness and hopelessness and 19% seriously considering suicide (

2). Pandemic-related stressors and routine disruptions, including school closures, affecting students and families have also potentially exacerbated mental health challenges and contributed to poorer mental health outcomes for many students (

3–

5). An analysis of syndromic surveillance data indicated that emergency department (ED) visits for attempted suicide among girls ages 12–17 years were 51% higher in February–March 2021 compared with the same period in 2019; ED visits due to suspected suicide attempt among boys ages 12–17 also increased by 4% from 2019 to 2021 (

6). Further, a robust body of literature has identified child and adolescent mental health disparities related to race, socioeconomic status, and adverse experiences (

1,

7,

8).

Amid the pandemic, recognition increased that schools are instrumental in facilitating the provision of myriad services that extend beyond academic resources (

9). Indeed, schools serve an integral role in supporting students’ mental health by providing access to mental health programs, identifying students in need of additional support, and linking students to services (

10–

16). Schools are one of the primary providers of mental health supports for youths and serve as a primary point of entry to mental health services (

12).

Before the pandemic, school mental health initiatives were transforming with an emphasis on delivery of population-based services, such as schoolwide positive behavior supports, and on the establishment of multitiered frameworks to guide the provision of services such as response to intervention and multitiered systems of support (

17–

20). School and community partnerships have been essential to building schools’ capacity to provide mental health supports for diverse student populations (

21). Yet, the pandemic has exposed the challenges, including personnel shortages and fractured referral systems, that schools have faced in the delivery of mental health supports (

22,

23).

In response to evidence of growing needs of youths and as a call to action to strengthen systems of support, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association released a statement declaring a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health in 2021 (

24). Included among the recommendations for addressing this emergency was the need for strengthening school-based approaches to support children’s mental health. Likewise, the 2021 U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on protecting youth mental health highlighted eight strategies that schools could take to support youths, including implementing social-emotional learning programs, expanding the school health workforce, incorporating trauma-informed approaches, and increasing partnerships with community-based mental health providers (

25). In parallel, a portion of funds from the American Rescue Plan Act was allocated to the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, providing access to funding in support of mental health programming in schools (

26).

Information has begun to emerge regarding the extent to which schools could enhance implementation of school-based mental health supports amid the pandemic. A Kaiser Family Foundation report describes aspects of the school mental health landscape, noting that more than half of U.S. schools have worked toward increasing their mental health programming (

27). Our study offers additional information on specific mental health supports that schools implemented across a multitiered framework of mental health service delivery, including schoolwide programming, group and individualized interventions, and establishment of community partnerships to facilitate linkage to indicated treatment services. We also sought to identify disparities in implementation by school characteristics, such as school-level poverty, because schools may be particularly well positioned to implement mental health programming or provide mental health supports on the basis of existing resources, infrastructure, expertise, and staffing.

Methods

Data

The National School COVID-19 Prevention Study (NSCPS) included five Web-based survey waves that were sent to school administrators from June 2021 to May 2022 to examine school-based strategies to prevent COVID-19 transmission. The NSCPS sampling frame of U.S. K–12 public schools was developed from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Common Core and Market Data Retrieval (MDR) databases (

28,

29). Schools that were private, alternative, or run by the U.S. Department of Defense or had <30 students were excluded from the sampling. Schools providing services to a “pull-out” population in another eligible school were also excluded. A nationally representative stratified random sample of U.S. K–12 public schools stratified by level (elementary, middle, or high school), NCES locale (city, suburb, town, or rural area), and U.S. region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West) were invited to participate (N=1,602). The final sample consisted of schools from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with minimal clustering at the school district level. Survey weights were applied to account for nonresponse and design strata. Additional details about NSCPS methods are published elsewhere (

30).

Data presented in this article come from the second wave of the NSCPS, administered from October 5 to November 19, 2021, which was the first data collection period of the 2021–2022 school year. The NSCPS wave 2 survey was pilot tested with a sample of school principals (N=8) to solicit feedback on how to improve the questionnaire. A similar mental health module included in wave 2 was also included in the 2022 School Health Profiles questionnaire for principals. School Health Profiles is a set of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveys administered biennially to middle and high school principals and lead health education teachers (

31). Although these data were not available for pilot testing, the School Health Profiles questionnaire underwent cognitive testing with a sample of principals who were asked whether they understood each survey item and whether they could answer the questions. Feedback from both rounds of pilot testing was incorporated into the NSCPS survey. A total of 437 of 1,602 schools that were invited to complete the survey participated in wave 2 (a 27% response rate). Most survey participants were school principals (N=340); on completion, participants received a $50 electronic gift card. This study was approved by the ICF Institutional Review Board in accordance with CDC policies.

Measures

NSCPS wave 2 included a one-time module capturing 11 school-based mental health supports (see the online supplement to this article). Nine of the 11 items assessed the following current supports: schoolwide trauma-informed practices, universal mental health programs, facilitated cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) groups, small therapy groups, confidential mental health screening, prosocial skills training, provision of an employee assistance program (EAP), stress management training sessions for teachers and staff, and professional development for staff to recognize mental health needs among students. Two items assessed an increase or improvement in the following supports: expanded partnerships to support students’ mental health needs and added mental health or counseling staff. For many of these mental health supports, parentheticals with definitions or examples for survey participants were included. For example, “schoolwide trauma-informed practices” was defined as “efforts to ensure that all students, including those affected by trauma, are experiencing social, emotional, and educational success.” The examples of “positive behavioral interventions and supports, social-emotional learning programs or supports” were included in describing universal mental health promotion programs. (The online supplement provides the complete survey wording.) In addition, space was provided for respondents to enter any mental health programs or services offered at their schools that were not included in our survey. Three coders independently reviewed write-in responses and categorized them into existing response categories when applicable. Differences in coding were reconciled through discussion.

Five school-level characteristics were also examined: school level (elementary, middle, and high), NCES locale, school poverty level, having a full-time school nurse, and having a school-based health center (SBHC). The latter two characteristics were included as questions on the NSCPS survey. The MDR database, which contains information about U.S. schools, was linked to the NSCPS survey data (

29). For school level, elementary schools included schools with any grade K–4, middle schools included schools with any grade 7–8, and high schools included schools with any grade 10–12. Schools were categorized as being located in a town, suburb, city, or rural area on the basis of the NCES locale classification scheme (

28). School-level poverty was categorized on the basis of the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals (FRPM) from 2019 to 2020. Informed by previous work, we categorized high-poverty schools as those with ≥76% of students being eligible for FRPM; mid-poverty schools, between 26% and 75% of students eligible for FRPM; and low-poverty schools, ≤25% of students eligible for FRPM (

32,

33).

Analyses

Associations between 21 school characteristics (e.g., U.S. region, poverty level, and size of the student body) and participation in wave 2 of the NSCPS were previously examined (

34). Only one school characteristic was significantly associated with participation—schools low or below average in affluence (based on school socioeconomic status) were more likely to participate than were schools that were average or above average or high in affluence. Survey weights, created by incorporating nonresponse adjustment classes based on the affluence indicator and poststratification based on the design strata (i.e., school level, NCES locale, and region), were used in all analyses.

Using the survey package of R, version 4.1.2, we calculated and presented weighted prevalence estimates of school-based mental health supports (

35). We calculated the relative standard error (RSE) for all prevalence estimates; one estimate had an RSE >30% and was suppressed. We conducted chi-square tests to examine whether prevalence of school-based mental health supports varied by school characteristics. We fitted 11 logistic regression models in which each mental health support was the dependent variable, and school-level characteristics were included as independent variables. Adjusted ORs (AORs) and 95% CIs are presented; a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the participating schools, most were elementary (52%), followed by middle (26%) and high (22%) schools (percentages reported here and in the following were weighted). About a third of the schools were suburban (32%), followed by schools in a city (29%), rural area (25%), or town (13%). Most schools were at a mid-poverty level (58%) and had a full-time school nurse (60%). Only 17% of the schools had an SBHC.

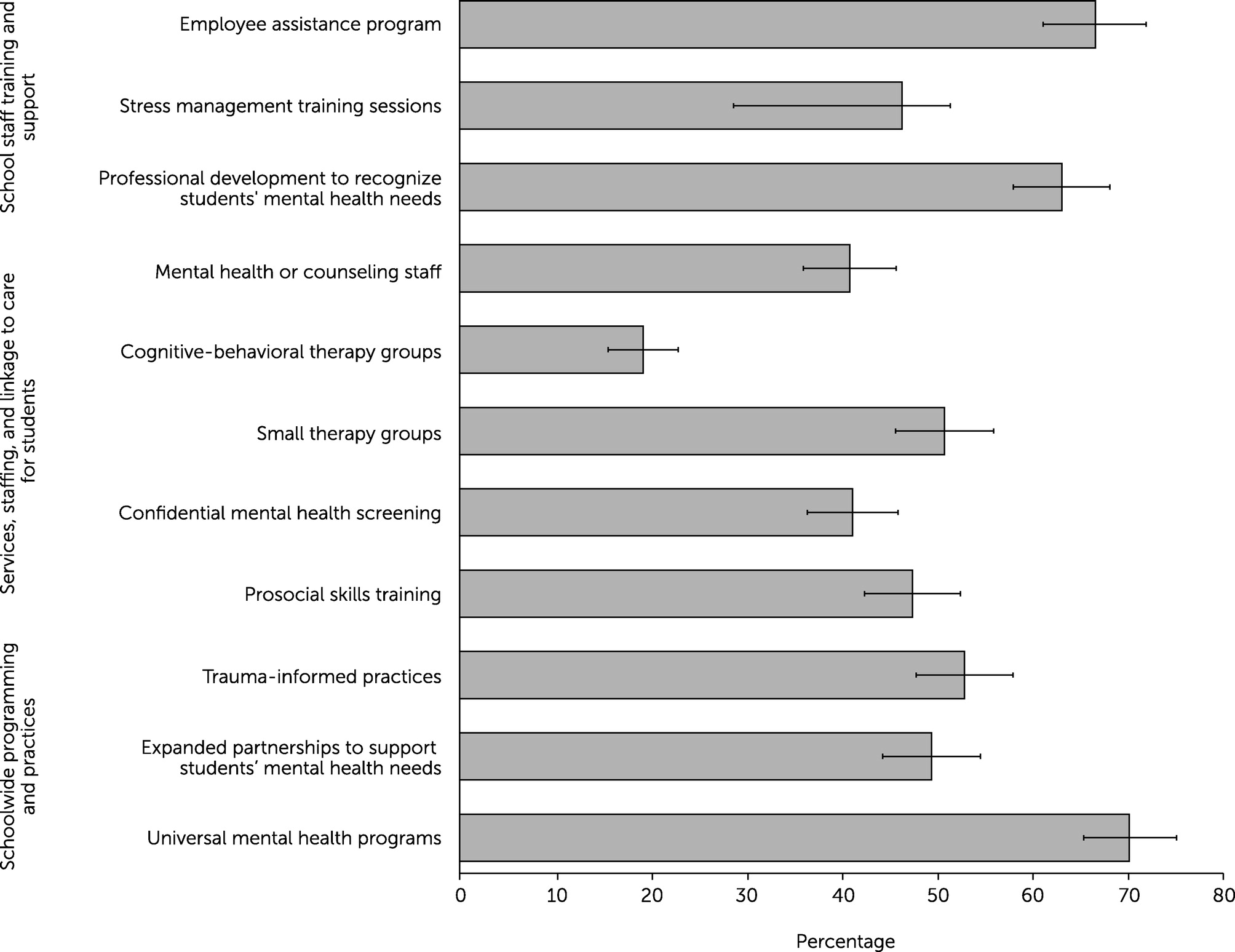

During the 2021–2022 school year, most schools reported providing universal mental health promotion programs (e.g., social-emotional learning) (70%), offering an EAP (67%), providing professional development to help staff recognize students’ mental health needs (63%), implementing schoolwide trauma-informed practices (53%), and having small groups for specific mental health concerns (51%) (

Figure 1). Less than half of the schools reported expanding partnerships to support students’ mental health needs (49%), implementing prosocial skills training for students (47%), offering stress management training sessions for staff (46%), providing confidential student mental health screening (41%), adding mental health or counseling staff (41%), or facilitating CBT groups for students (19%).

Unweighted estimates of mental health supports by school characteristics, weighted prevalence, and chi-square test results are presented in the

online supplement. Model estimates for associations between school characteristics and schoolwide mental health supports are presented in

Table 1; mental health services, staffing, and linkage to care for students in

Table 2; and mental health–related staff training and support in

Table 3. Adjusted regression analyses revealed that several disparities in implementation of school-based mental health supports persisted after adjustment for all examined school-level characteristics. Middle schools had higher odds of providing confidential student mental health screening to identify students in need of services (AOR=2.47), compared with elementary schools (

Table 2). High schools had higher odds of expanding student-support partnerships (AOR=2.93) (

Table 1) and providing confidential mental health screening (AOR=2.93) (

Table 2), compared with elementary schools. However, high schools had lower odds of implementing prosocial skills training (AOR=0.50), compared with elementary schools (

Table 2). Compared with city schools, rural schools had lower odds of providing EAPs (AOR=0.28) and providing staff stress management training (AOR=0.41) (

Table 3). Similarly, compared with city schools, schools in towns had lower odds of providing EAPs (AOR=0.23) and providing staff stress management training (AOR=0.34). Compared with low-poverty schools, mid-poverty schools had lower odds of implementing prosocial skills training for students (AOR=0.49) and providing confidential mental health screening (AOR=0.42) (

Table 2). Similarly, high-poverty schools had lower odds of implementing prosocial skills training (AOR=0.44), compared with low-poverty schools. Schools with a full-time nurse had higher odds of providing stress management training for staff (AOR=1.70) (

Table 3), and schools with an SBHC had higher odds of implementing schoolwide trauma-informed practices (AOR=2.48) (

Table 1).

Discussion

This study provides a snapshot of the supports that U.S. schools implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic to help meet their students’ mental health needs, revealing disparities in implementation of supports by school-level characteristics. Our results highlight myriad efforts that schools were taking to support students and staff, including schoolwide programming and therapeutic support for students with specific needs. However, marked disparities in implementation also suggest that the capacity of many schools to provide mental health supports may be limited and needs bolstering, especially in low-income and rural communities.

Although more than half of the schools were implementing several initiatives to support the mental health of their students, the prevalence of certain schoolwide mental health supports was suboptimal. For example, only 53% and 49% of schools implemented trauma-informed practices and expanded partnerships for student support, respectively. These represent actions schools can take to support the mental health of all students and establish a foundation for early intervention and treatment for students with additional needs.

Furthermore, it is imperative that implementation of school-based mental health supports be equitable. Mid- and high-poverty schools and schools located in rural areas or towns were less likely to have certain mental health supports (e.g., prosocial skills training and confidential mental health screening for students) in place than were city and low-poverty schools. Implementation of mental health supports depends on resources such as funding and training to expand teachers’ capacity to implement universal strategies. Also, schools face competing demands, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, schools may be especially well positioned to provide specific mental health supports and navigate opportunities to access supplemental funds. Elementary schools were less likely to have mental health supports such as confidential mental health screening. There are several explanations for this disparity, including possible underestimation of the need for services for this population. Early intervention not only can be integral to promoting positive mental health outcomes among youths but also can facilitate greater mental health care engagement throughout the life course (

14). Additionally, previous research has shown that children living in rural areas or from low-income families and neighborhoods experience substantial barriers to mental health care (

36). This study extends this literature by identifying similar disparities in school settings. In fact, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on protecting youth mental health identified low-income youths and youths living in rural areas as being at increased risk for mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may require more tailored outreach efforts (

25). Schools with full-time nurses and those with SBHCs were more likely to provide specific mental health supports. The presence of health infrastructure and personnel within schools may contribute to greater capacity to provide such supports.

Schools also are a setting where teachers and other staff can receive mental health support. Teachers facing high stress during the pandemic may have experienced difficulties in teaching effectively and coping with routine stressors (

37). Creating a comprehensive system of mental health supports, including initiatives to support teacher well-being, can benefit both teachers and students, fostering a positive learning environment that complements effective teaching. However, several barriers to the implementation of mental health programs in schools have been identified, such as competing responsibilities, logistic challenges, and lack of districtwide and state-level support (

38). Dedicated funding for mental health and community partnerships has been identified as facilitator of mental health supports that may help ensure that schools possess adequate resources and capacity to implement mental health initiatives effectively (

38).

This study had several limitations. The response rate of 27% was low. School affluence was significantly associated with NSCPS participation, with schools that were low or below average in affluence being more likely to participate than schools that were average or above average or high in affluence. To help address nonresponse bias, survey weights incorporating nonresponse adjustment classes based on the affluence indicator and poststratification based on the design strata (i.e., school level, NCES locale, and U.S. region) were used; however, these findings still may not be generalizable to all U.S. public schools. Implementation of school-based mental health supports was self-reported by school respondents, primarily principals, who may be limited in their knowledge of the extent of all supports available, which may have resulted in underreporting. In contrast, social desirability biases might have resulted in overreporting. Fidelity, participation, and quality of specific supports were not assessed. Two supports (expanded partnerships to support students’ mental health needs and added mental health or counseling staff) were used to assess improvement in school-based mental health supports in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, we did not have data on these supports before the pandemic, limiting the interpretability of the findings.

Conclusions

Overall, the levels of implementation of school-based mental health supports leave substantial room for improvement, and we found numerous disparities in these supports arising from school characteristics. All schools may benefit from additional resources and assistance in implementing mental health supports for students and staff. Elementary, rural, town, and mid- and high-poverty schools as well as schools without a health infrastructure may require more assistance to ensure equitable access of students to mental health supports during public health emergencies.