The COVID-19 pandemic placed significant strain on an already overwhelmed U.S. health care system and significantly disrupted access to health services. Additionally, the pandemic triggered an increase in mental health challenges and substance use (

1). The highest numbers of drug overdose deaths ever to be recorded occurred in 2020 and 2021, with most deaths involving opioids; opioid overdose deaths increased from about 70,000 in 2020 to >80,000 in 2021 (

2). In the face of pandemic-related stress and because access to treatment was already tenuous before the pandemic, persons with opioid use disorder were particularly vulnerable to disruptions in treatment for opioid use disorder after the pandemic’s onset.

Access to treatment for opioid use disorder is critical to the health and well-being of people with opioid use disorder. Guideline-concordant primary treatment options include care provided in an outpatient setting and approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD; i.e., buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone) (

3). Treatment for opioid use disorder, particularly MOUD, is associated with reduced cravings and withdrawal symptoms, abstinence from opioid use, and reduced risk for overdose (

4). Disruptions to such a treatment could therefore lead to negative outcomes, including overdose. Policies intended to increase treatment access and mitigate disruptions in ongoing care, such as expanded telehealth services, increased methadone take-home flexibilities, and fewer restrictions on buprenorphine prescribing, were implemented early in the COVID-19 pandemic (

5,

6).

Research examining early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on care has shown little change in opioid use disorder treatment utilization overall, including opioid use disorder care in outpatient settings (

7,

8) and buprenorphine treatment (

9–

13), but has indicated an increase in the use of telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment (

7,

8,

14). However, most studies examining utilization of opioid use disorder treatments before and after the start of the pandemic did not disentangle pandemic-related treatment disruptions among patients who were already engaged in treatment prepandemic from pandemic-induced treatment demand by patients with new-onset opioid use disorder (

8–

10,

12). Two previous studies examined treatment trends among adults receiving opioid use disorder treatment before the pandemic (

7,

13). These studies reported little change in overall utilization of opioid use disorder treatment in the pandemic’s first 6 months (

7,

13) and observed an increase in telehealth-delivered treatment from March to May 2020 (

7). We noted a lack of research examining potential shifts in care utilization trends in the latter phases of the pandemic among patients receiving opioid use disorder treatment before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study fills an important gap by exploring potential pandemic-related disruptions to opioid use disorder outpatient care and MOUD treatment among people engaged in opioid use disorder treatment prepandemic.

Methods

We used deidentified administrative insurance claims in the OptumLabs Data Warehouse (

15) records from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2022, to examine potential COVID-19–related disruptions in outpatient and MOUD treatment among persons already receiving opioid use disorder care before the pandemic. To this end, we created a longitudinal cohort of patients with continuous insurance coverage and used data from the March 2018–February 2019 period to capture prepandemic treatments for an opioid use disorder diagnosis. The sample included adults ages ≥18 years (N=13,113) with continuous medical, pharmacy, and mental health coverage via commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2022, and an insurance claim indicating inpatient or outpatient treatment for an opioid use disorder diagnosis (see section A of the

online supplement to this report for

ICD diagnosis codes) between March 1, 2018, and February 28, 2019. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Outpatient and MOUD treatment outcomes were assessed between March 1, 2019, and February 28, 2022, to examine trends in the year before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and then in the 2 years following its onset. We measured the proportion of patients with any claim for opioid use disorder outpatient treatment per month, as well as the proportion of patients who received MOUD for each month. For MOUD, we used both pharmaceutical and medical claims to identify medication fills and medication administration visits. Among patients receiving outpatient treatment for opioid use disorder, we measured the proportion of patients who had only in-person visits, only telehealth visits, or both in-person and telehealth visits in a given 12-month period. (All codes used to identify services and medications are presented in section A of the online supplement.)

To examine utilization of opioid use disorder outpatient and MOUD treatments, we calculated the proportion of patients with any of the medical or pharmaceutical claims of interest. Using ordinary least-squares regression and data from March 2019 to February 2020, we calculated predicted proportions of patients with any claim for opioid use disorder outpatient treatment and any MOUD treatment claim from March 2020 to February 2022 to estimate trends in care utilization during this timeframe had prepandemic utilization trends continued on the same trajectory. We then plotted the actual and predicted proportions for each month. Additionally, we calculated the percentage-point differences between actual and predicted values in each month after pandemic onset. To examine the distribution of in-person and telehealth outpatient visits, we calculated the annual proportion of patients receiving opioid use disorder outpatient treatment who had only in-person visits, only telehealth visits, or both in-person and telehealth visits.

Because it is possible that patients included in the primary sample had different care utilization patterns (i.e., for those with a new diagnosis vs. those in long-term treatment), we repeated the analyses with a second sample of patients likely to have received a new diagnosis of opioid use disorder in 2018. This sample included adults who had continuous insurance coverage from March 1, 2016, to February 28, 2022; did not have opioid use disorder diagnosis claims from March 1, 2016, to February 28, 2018; and did have opioid use disorder diagnosis claims between March 1, 2018, and February 28, 2019.

Results

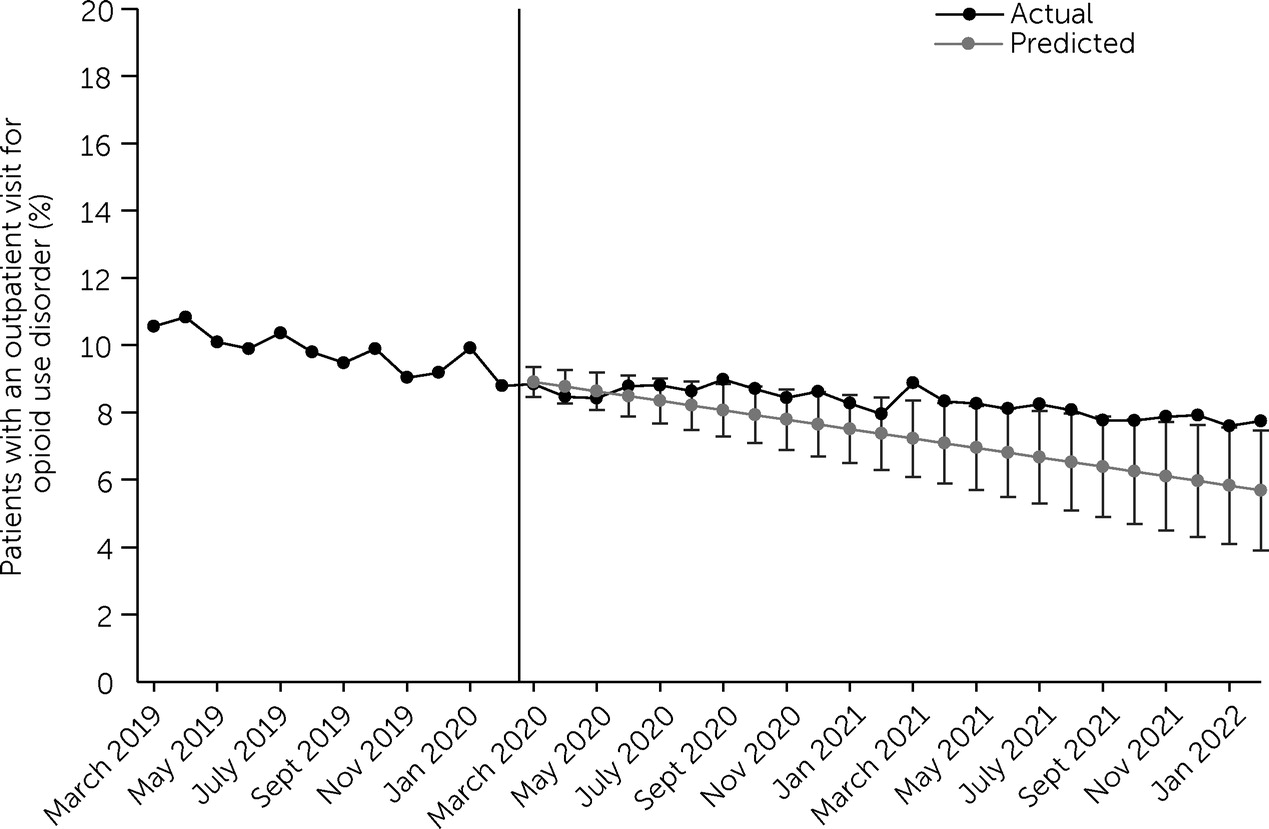

In the sample of adult patients receiving treatment for an opioid use disorder diagnosis between March 2018 and February 2019, we examined treatment utilization between March 1, 2019, and February 28, 2022, to examine trends in the year before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the 2 years after its onset. The proportion of those who had an outpatient or MOUD treatment visit in a given month was low and relatively stable before the pandemic and after its onset. In March 2019, 10.6% (N=1,390) of the patients had an opioid use disorder outpatient visit, declining to 7.8% (N=1,023) in February 2022. The actual proportion of patients with an opioid use disorder outpatient visit between March 2019 and February 2022 declined by 2.8 percentage points; this decline was slightly less than predicted for the March 2020–February 2022 period (

Figure 1). In March 2019, 7.8% (N=1,023) of patients received MOUD. Between March 2019 and February 2022, we observed a decline of 0.3 percentage points in the proportion of persons receiving MOUD (see section B of the

online supplement). For MOUD, the difference in actual and predicted proportions was <1.5 percentage points throughout the study period.

Between March 2019 and February 2020, 98.6% (N=3,436 of 3,485) of the patients who received outpatient opioid use disorder treatment obtained care via in-person settings only (see section C of the online supplement). Between March 2020 and February 2021, 46.0% (N=1,333 of 2,900) of the patients received at least some opioid use disorder treatment via telehealth, 34.6% (N=1,002) received a combination of telehealth and in-person care, and 11.4% (N=331) received services solely via telehealth. From March 2021 to February 2022, 34.9% (N=960 of 2,749) of the patients received at least some outpatient care via telehealth, 23.4% (N=643) received both telehealth and in-person care, and 11.5% (N=317) received care via telehealth only (see section C of the online supplement). Results for the sample of patients having a new diagnosis of opioid use disorder in 2018 (N=3,178) were similar to the findings in the primary sample (see section D of the online supplement).

Discussion

Patients receiving opioid use disorder treatment before the COVID-19 pandemic had only small changes in utilization of outpatient services and MOUD treatment during March 2019–February 2022. Our results align with previous work encompassing the early months of the pandemic (

7,

13), suggesting that patients already engaged in care could continue treatment during the pandemic despite broad disruptions in health care delivery. We did observe a slight downward trend in utilization of outpatient treatment for opioid use disorder. This decline may be explained by individuals needing less frequent visits over time or could have been related to changes in service delivery. It is also possible that demand for care increased after the start of the pandemic, but because in-person services became less available, patients were unable to access treatment, even with the expansion of telehealth.

Telehealth utilization for opioid use disorder was minimal before the pandemic and increased at the start of the pandemic, a trend that continued through February 2022. Adoption of telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment likely helped mitigate disruptions in outpatient and MOUD care (

14,

16). During the pandemic, state and federal agencies temporarily eased restrictions on reimbursement of addiction services delivered via telehealth, and many of these policies have now been made permanent (

17). Additionally, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration proposed updates to federal rules, including permanently allowing flexibilities in telehealth treatments for opioid use disorder (

6), which could help reduce access barriers for outpatient and MOUD care.

Our findings suggest that telehealth did not completely replace in-person services for opioid use disorder in either the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic or 2 years after its onset. Several reasons may account for this incomplete replacement. Provider and patient preferences influence the uptake of telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment. Findings from interviews and surveys of addiction treatment providers suggest that uptake of telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment was large after pandemic onset and that telehealth helped mitigate treatment disruptions (

16). However, providers reported continued use of in-person services or a combination of in-person and telehealth modalities (

16). Moreover, patient perspectives have suggested the need for flexibility in the use of treatment modalities. In one study, 21% of patients engaged in MOUD treatment preferred a combination of telehealth and in-person visits and emphasized the importance of this flexibility to enhance treatment access (

18). Results from these studies highlight the need for flexible, patient-centered care. Additional research on the efficacy of telehealth-delivered opioid use disorder treatment, alone and in combination with in-person treatment, is needed.

This study had several limitations. The sample included adults with continuous enrollment in commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance. Generalizability to other populations, including those with Medicaid or Medicare and those who are uninsured or with inconsistent coverage, may be limited. Additionally, we did not examine differences by geographic or sociodemographic characteristics. Because this study used insurance claims, we could have missed services not covered by insurance, which is particularly relevant for methadone treatment. Telehealth visits prepandemic could have been undercounted because of the lack of telehealth billing codes and coverage prior to 2020. We also were unable to accurately track audio-only visits, given the lack of billing standards for this type of service. Last, we could not assess the clinical appropriateness or quality of the opioid use disorder services used by patients in our sample.

Conclusions

Among a group of adults with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage who had received opioid use disorder treatment before the COVID-19 pandemic, we observed minimal changes in outpatient and MOUD treatment utilization in the 2 years after pandemic onset. The pandemic prompted increases in delivery of opioid use disorder treatment via telehealth, with more than a third of patients receiving opioid use disorder treatment via telehealth between March 2021 and February 2022. Additionally, the pandemic spurred widespread policy changes, including flexibility in the delivery of telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment, that may have enhanced treatment access. Future research may examine how these policies affect receipt of care and explore how to optimally target in-person, telehealth, or a combination of treatment modalities to patients with opioid use disorder.