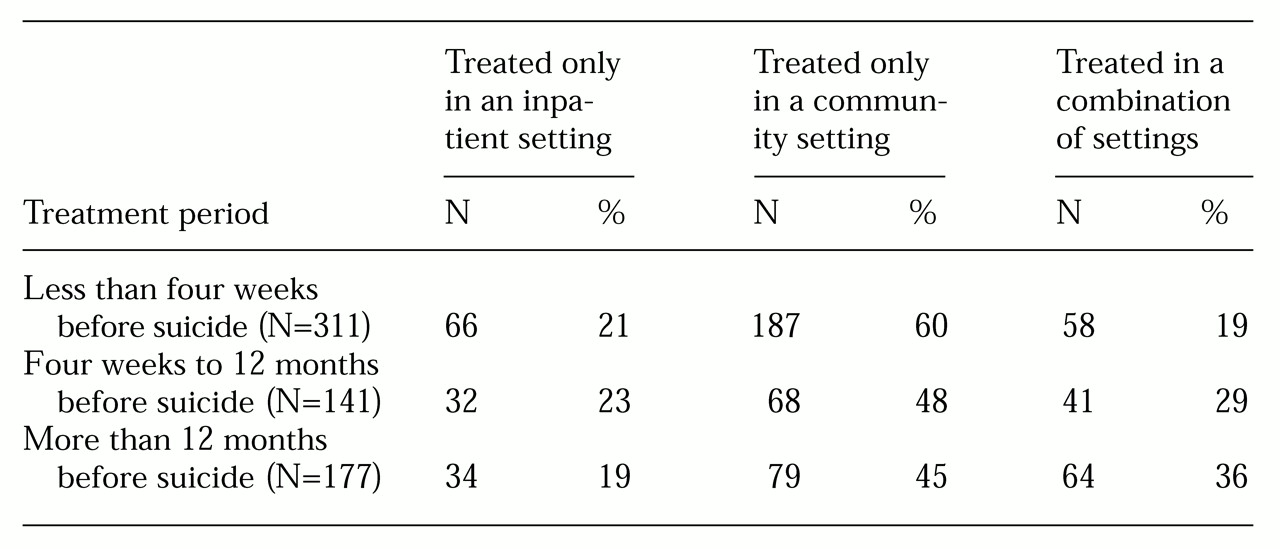

The study identified 2,638 suicides in Victoria over the five-year period. A total of 629 suicides (24 percent) were by people who had a history of contact with Victorian public psychiatric services; 452 (17 percent) had received public-sector care during the previous 12 months, and 311 (12 percent) had done so within four weeks of death.

Patient characteristics

The patients who committed suicide were predominantly male and relatively young. A total of 454 of the 629 patients were male (72 percent). Three hundred of the males (66 percent) and 89 of the females (51 percent) were under 40 years old. Many of the patients (303, or 51 percent) were unmarried, and 173 patients (28 percent) were socially isolated at death. Social isolation was defined as "not in regular contact with friends, if any, or family, if any."

A diagnosis was available for 599 of the 629 patients. Of these, 215 (36 percent) had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 123 (21 percent) had manic-depressive psychosis or major depression, 119 (20 percent) had neurotic depression, and 142 (24 percent) had other nonpsychotic or personality disorders.

A total of 418 patients (66 percent) had made at least one previous suicide attempt. One hundred forty-eight patients (24 percent) had made one previous attempt, 98 (16 percent) had made two, and 172 (27 percent) had made three or more.

Many patients had a pathological family history. A total of 371 patients (59 percent) had a history of childhood problems. Such problems included parental separation; severe parental conflict; a chaotic family life; living with others for significant periods of time; foster care; neglect; a critical-hostile or cold-distant relationship with parents; parental alcoholism, psychiatric illness, physical illness, or drug abuse; and other trauma. A total of 236 (36 percent) had a family history of psychiatric illness, and 86 (14 percent) had a family history of suicide. Such family histories were common across diagnostic clusters.

Of the 629 patients, 114 (33 percent) had a history of violence to others or to property, and 163 (26 percent) had been involved with the justice system, including court appearances, significant police involvement, forensic psychiatric treatment, and involvement with a youth training center. A total of 307 (49 percent) had a history of drug or alcohol abuse.

Judgments of preventability

The auditors believed that 125 of the suicides (20 percent) could have been prevented had the service system responded differently. The auditors cited several factors in their judgments.

Assessment factors. In terms of assessment factors, judgments of preventability were most commonly associated with suboptimal staff-patient relationships (in 78 cases, or 62 percent).

The auditors cited poor or incomplete assessment of suicide risk in 74 cases (59 percent), concluding that the patient's suicide risk was not adequately ascertained or its level not given due weight.

The auditors also cited poor assessment of symptoms that were not specific criteria for the patient's diagnosis. For example, affective symptoms were sometimes overlooked in the absence of a diagnosis of an affective disorder. Poor assessment of depression or psychological issues was among the reasons for judgments of preventability for 19 of the 45 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder whose suicides were considered preventable (42 percent). Poor assessment of depressive symptoms was cited in the case of four of the 20 patients with other nonpsychotic or personality disorders whose suicides were judged preventable (20 percent).

Also associated with judgments of preventability were poor assessment of current functioning (14 patients, or 11 percent) and poor history taking (13 patients, or 10 percent).

Cross-setting treatment issues. For 30 suicides judged to be preventable (24 percent), the auditors noted that no documented counseling for psychological problems occurred, or, if it did, it was inadequate. The auditors also cited inadequate treatment of depression (20 cases, or 16 percent).

Inpatient treatment issues. In the case of 24 preventable suicides (19 percent), the auditors cited poor quality of the inpatient staff-patient relationship as a reason for their judgment.

Other inpatient treatment issues cited were poor communication between inpatient staff (15 cases, or 12 percent), inappropriate discharge (12 cases, or 10 percent), and insufficient planning or action regarding leave (11 cases, or 9 percent).

Community-based treatment issues. A judgment of preventability was sometimes based at least partly on the auditors' perception that the response to suicide risk by a community team was inadequate. In 19 of the cases (15 percent), the inadequate response occurred when patient care was the responsibility of a continuing care team. The auditors cited excessive time between appointments with a continuing care team for 16 preventable suicides (13 percent).

The auditors based their judgments of preventability on poor relationships between the patient and a continuing care team in 14 cases (11 percent) or a crisis assessment and treatment team in six cases (5 percent). For six preventable suicides (7 percent), the auditors based their judgment on a reduction in or change of medication.

Continuity-of-care issues. Twenty-nine of the preventable suicides (23 percent) were attributed, at least partly, to continuity-of-care issues, because the patient was not admitted to an inpatient unit, the patient was refused admission, or admission could not be arranged. In 11 of the preventable cases (9 percent), the auditors stated that the patient was refused services or offered limited services by a continuing care team. Refusal or abrupt termination of services by a crisis assessment and treatment team was given as a reason in 38 cases (30 percent).

In 25 preventable suicides (20 percent), the judgment was based on the fact that the patient appeared to need but did not receive assertive community follow-up.

Poor transition between services was also cited. Twenty of the preventable suicides (16 percent) were attributed to poor transition at least in part because the patient had been poorly transferred or discharged from a community mental health center.

The loss of or change in case manager was given as a reason in 15 cases (12 percent), presumably where termination issues and the transition to a new case manager were not dealt with adequately.