Little is known about the long-term costs of chronic diseases in general or about depression specifically. The National Institute of Mental Health has solicited research projects addressing the cost of illness (

1). Cost studies help policy makers allocate limited resources for research and treatments to areas of greatest need and largest potential impact.

Depression is economically important. The direct costs for affective disorders in the U.S. were estimated at $12.2 billion in 1985, or 3.3 percent of total personal health care spending for all illnesses (

2). The total economic burden was estimated at $20.8 billion in 1985 and $30.4 billion in 1990 (

2). Another estimate put the direct costs of depression at $12.4 billion in 1990 and the total economic burden at $43.7 billion (

3).

Large-scale estimates (

2,

3) are based on assumptions and extrapolations, not patient records. Smaller studies are based on small samples that document the experience of selected populations (

4). The generalizability of their results is questionable. An additional problem is that study periods are usually short and rarely follow patients through multiple hospitalizations.

In this study, we determined the patterns of long-term hospital costs for depression in different hospital settings in Nova Scotia over a three- to six-year follow-up period. The study required tracking 4,383 individuals through all of their psychiatric hospitalizations. The hospital settings were general hospital nonspecialized units (general wards), psychiatric units in general hospitals or specialized psychiatric hospitals (specialized units), and mixed hospital settings. A mixed hospital setting refers to a situation in which a patient has been admitted at least once to a general ward and at least once to a specialized unit. Hospitalizations in different settings have been compared in only a few studies (

5,

6). Those that did often inferred the type of hospital setting (

6).

We studied the entire population of the province of Nova Scotia, which had a 1990 population of 893,100. Canada has universal, single-payer insurance coverage for all residents. Mental illnesses have parity with physical illnesses. There are no mental health exclusions, no limits, and no deductibles for hospital care. No financial incentives exist for either the physician or the hospital to differentially treat patients. Everyone has the same mental health coverage. Furthermore, Canada has no centralized system of managed care. Medical treatment, such as the decision to hospitalize and the length of stay, is determined at each hospital.

This study analyzed hospitalization costs exclusively. Hospital costs constitute the largest component of health care expenditures. Because hospitalizations involve more severe cases of clinical depression, there is little likelihood of missed or undiagnosed severe depression, a phenomenon that allegedly exists when cases are less severe (

7).

Nova Scotia has a long-standing government policy of promoting the decentralization of medical care and building small, local hospitals so that patients can be hospitalized within their own communities. The treatment of psychiatric illnesses is complicated by the shortage of psychiatrists and specialized psychiatric hospital beds, as well as by the geographic concentration of psychiatrists and beds in the larger cities and towns. As a result of either of these limitations or the desire to be treated close to home, psychiatric patients from rural communities are often treated in their small local hospitals in nonspecialized wards by their family physicians.

Methods

This study analyzed the Nova Scotia Longitudinal File (NSLF), a database created by AlgoPlus Consulting Limited in collaboration with the Nova Scotia Department of Health. The NSLF is a statistical psychiatric database that includes all hospitals (general and psychiatric) in Nova Scotia. Patient confidentiality was maintained through the use of a Nova Scotia Department of Health encryption algorithm, which transformed the patient identifiers in a consistent manner. All hospitalizations over the study period for individual patients were cumulated and organized by the patient identifier, which enabled analysis of the longitudinal course and costs of hospital care (

8).

The study group consisted of all patients who were age 18 years or older at first hospitalization and who had a primary diagnosis of any mental disorder as well as a depressive-spectrum diagnosis between January 1, 1989, and December 31, 1991.

Specifically, all patients included had to have an ICD-9 diagnosis of depression during the period from 1989 to 1991. The diagnoses included the affective psychoses (ICD-9 codes 296.1, 296.3, 296.4, 296.5, 296.6, 296.8, and 296.9), neurotic depression (code 300.4), affective personality disorder (code 301.1), and depression not elsewhere classified (code 311).

Hospital costs were cumulated from the first hospitalization during 1989 through 1991 until December 31, 1994, which constituted a three- to six-year follow-up period. Hospital costs were calculated by multiplying the number of patient days in each hospital setting by the cost per patient day determined by the Nova Scotia Department of Health in 1994 Canadian dollars.

Results are reported in May 1998 U.S. dollars. First, the 1994 Canadian dollars were transformed into May 1998 Canadian dollars using the Statistics Canada Consumer Price Index (1994 Canadian dollars were multiplied by 108.7 divided by 103.8). Next, the May 1998 Canadian dollars were transformed into May 1998 U.S. dollars at the May 15, 1998, noon exchange rate of .6894. The costs per hospital day were $289 U.S. 1998 ($400 Canadian 1994) for general wards in general hospitals, $399 U.S. 1998 ($552 Canadian 1994) for psychiatric units in general hospitals, and $321 U.S. 1998 ($445 Canadian 1994) for units in psychiatric hospitals.

Results

Between 1989 and 1991, a total of 4,383 individuals were hospitalized in Nova Scotia for depressive disorders, for a rate of seven patients per 1,000 population.

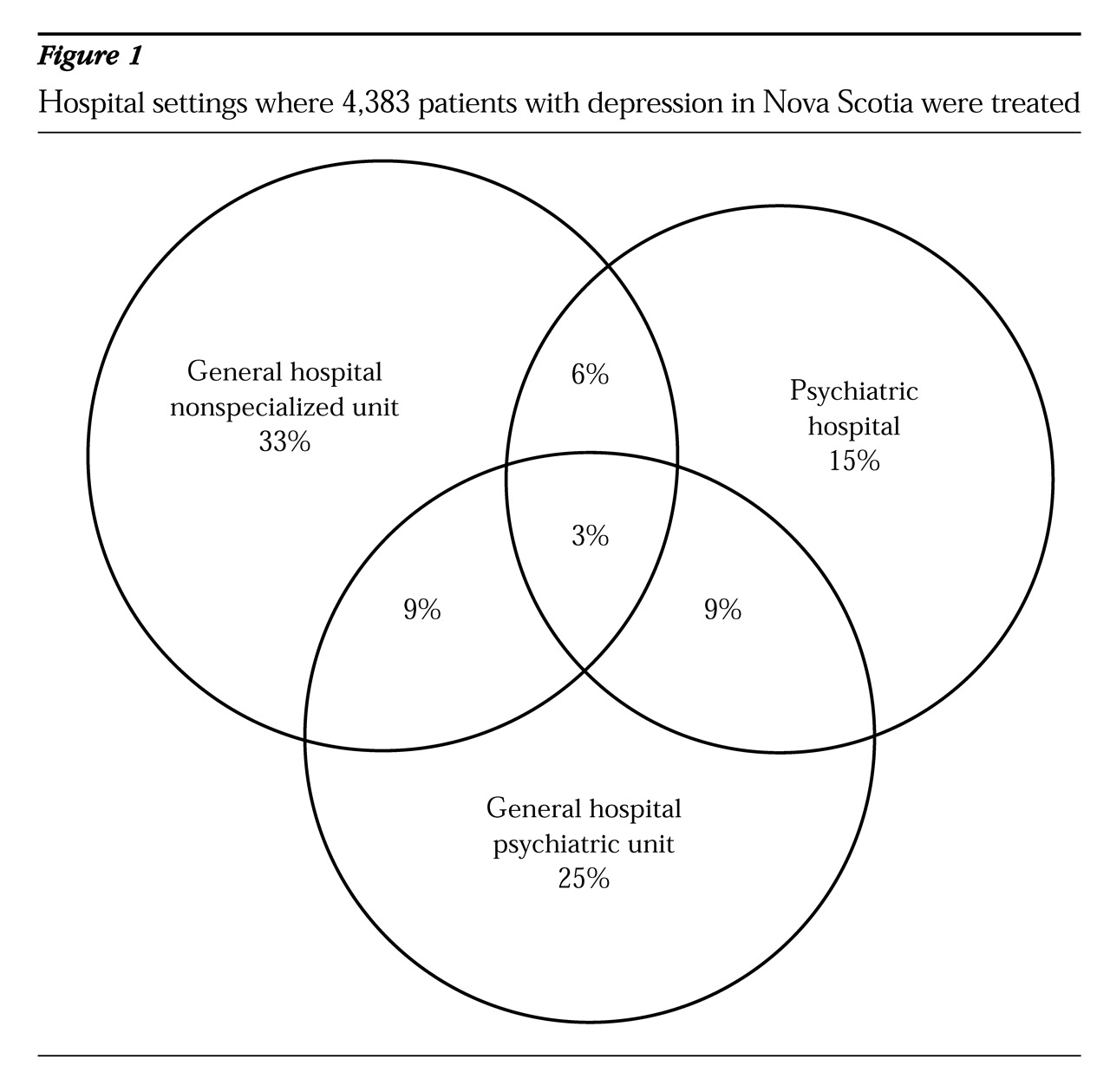

As

Figure 1 shows, 51 percent of the 4,383 patients (N=2,217) were hospitalized at least once in nonspecialized general hospital wards; 33 percent (N=1,427) were hospitalized exclusively in this setting, and 18 percent (N=790) were hospitalized in mixed settings. Forty-nine percent of the 4,383 patients (N=2,166) were hospitalized exclusively in specialized units, either in general hospitals or in psychiatric hospitals.

Over the three- to six-year follow-up, the mean±SE cumulated hospital cost per patient was more than six times higher in specialized units than in general wards—$30,266±$1,026 versus $4,729±$173. Those treated in mixed settings had a mean cumulated hospital cost of $29,422±$1,301, which was similar to the cost for those hospitalized in specialized units.

Within the same hospital setting, marked variability was noted in cumulated costs per patient. The coefficient of variation was 138 percent for general wards and 158 percent for specialized units, which means that relative to their means, the cumulated costs within general wards varied less than within specialized units.

The distributions of cumulated costs were skewed. The 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th cost percentiles for patients treated exclusively in specialized units were $2,888, $8,361, $22,842, and $54,052, respectively. The same figures for patients treated exclusively in general hospital nonspecialized wards were $1,155, $2,599, $5,487, and $10,107.

Although the mean cumulative cost for all patients with depression was $21,800 per patient, the mean was only $3,376 per patient for the patients in the lower-cost half of the sample. The mean cumulated hospital costs were $66,304 for a patient in the top quartile and $111,644 for a patient in the top decile.

Discussion and conclusions

In Nova Scotia, .7 percent of the adult population (age 18 and over) was hospitalized for clinical depression during 1989–1991. This finding conflicts with the general perception of massive unrecognized need due to missed diagnoses of depression. Upper-limit estimates of three-year hospitalization rates of .39 to .75 percent can be derived by making four assumptions (

9). The first is that all mood disorders during one year, 7.1 percent according to the U.S. Surgeon General's recent report (

10), are depression. The second assumption is that all cases in which depression is recognized, 35 percent according to one recent study (

11), are cases of major depression (35 percent × 7.1 percent = 2.5 percent). The third assumption is the Surgeon General's estimate that 5 to 10 percent of cases of major depression require hospitalization (

10) (5 percent × 2.5 percent = .13 percent to 10 percent × 2.5 percent = .25 percent). The fourth assumption is that the three-year rate of hospitalization would be three times the one-year rate, which would result in a hospitalization rate in the adult population of .39 to .75 percent. The actual Nova Scotia hospitalization rate for depression of .7 percent is at the high end of this theoretical upper limit.

A major methodological contribution of this paper has been determining longitudinal hospital costs for depression. Major cost differences were found between hospital settings. The mean cumulated cost for patients hospitalized only in nonspecilized wards was $4,729, or 85 percent less than the cost of hospitalization for those hospitalized only in specialized units, which was $30,266. Similar disparities between costs for hospital care have previously been reported (

6).

If such studies are to have an impact on policy, further analyses are required to confirm that the differences in hospital costs for depressed patients in Nova Scotia were not the results of severity or complexity of illness. We have previously reported that nonspecialized wards in general hospitals treat patients who are older than those treated in specialized units (

12). The older patients would be expected to be a more complex patient group. The assumption that additional days of hospitalization enhance patient outcomes has been shown to be dubious in research on hospital cost-containment pressures of prospective payment systems (

6,

13).

Severity of depression is difficult to determine. Available methods are limited and lack rigor. We have no equivalent of the Apgar score for newborns. Current methods include a symptom count as in the Hamilton Depression scale, diagnosis-related-group classification, proprietary algorithms that are not disclosed (

14), and an examination of the clinical course of care, encompassing previous history, complications, rehospitalizations, and resource use (costs).

In comparing patients, it would be useful to answer four questions. First, are similar proportions of patients with specific diagnoses treated in general wards and in specialized units? Second, what is the influence on costs of gender, age, geographic proximity to the hospital, previous hospitalizations, and comorbidity? Third, among patients hospitalized in both specialized and nonspecialized settings, what is the sequence of hospitalization settings? Fourth, what are the intervals between hospitalizations for patients treated in general wards and in specialized units?

Major variations in hospital costs were found within the same hospital setting. This finding is consistent with findings about treatment of depression in the Veterans Affairs health care system (

15), which has standardized treatment protocols. Twenty-nine percent of VA medical centers reported mean lengths of stay for their patients with depression that were significantly different (p<.01) from the mean in the study sample.

In our study the distribution of costs was skewed. In a nonselected hospitalized population of patients with depression from which no patients were excluded, 10 percent of the patients accounted for 51 percent of the hospital costs. The mean per-patient cost for all of the hospitalized patients with depression was $21,800. However, the mean cost for a patient in the decile with the highest costs was $111,644. Among patients in specialized settings, the mean cost was $30,266, while the median cost was $8,361. A few high-use patients had a major impact on the overall system costs. This finding has important implications regarding future long-term costs resulting from mental health parity legislation in the United States.

This study confirmed that nonspecialized wards in general hospitals play a major role in hospitalizing depressed patients. Economic studies of depressive disorders must include these wards.