The relationship between patients' satisfaction with services and the outcomes of those services is poorly understood. In this study, it was hypothesized that service satisfaction is related to self-reported mental health status and increases in life satisfaction. To test this hypothesis, the relationships between service satisfaction and self-reported measures of mental health and life satisfaction were examined in a survey of 815 persons who received mental health services.

Methods

A stratified random sample of 2,530 persons was selected from 16,579 Medicaid recipients between the ages of 18 and 64 who received mental health services under Iowa's Medicaid fee-for-service plan in fiscal year 1993. Subjects were identified through Medicaid claims records. The sample was stratified according to the diagnosis listed on the Medicaid service claim, urban or rural county of residence, and illness severity, which was defined as high if the respondent had an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization in fiscal year 1993 and low if the respondent had not. The four diagnostic categories were schizophrenia (schizophrenia and schizoaffective illness), affective disorders (major depressive disorder and bipolar illness), anxiety disorders (panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder), and adjustment disorders. Within each category of the stratified sample, subjects were randomly selected. Subjects who did not respond to the first mailing of the survey instrument received a second survey approximately one month after the first mailing.

The survey items used as study variables are available from the first author. Life satisfaction questions were modified from the Quality of Life Index for Mental Health developed by Becker and associates (

1). Because patient satisfaction with the patient-provider interaction has been shown to influence the outcome of care (

2,

3,

4,

5), questions about service primarily assessed the quality of the interpersonal experience with providers. Self-reported mental health status was measured on a scale of 1, poor, to 5, excellent.

Self-reported service satisfaction and life satisfaction over the past six months were each assessed by eight items, which were rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 7. An aggregate scale of service and life satisfaction was calculated and scored, with 0 as the most negative response and 1 as the most positive. The scales displayed evidence of good test-retest reliability and face validity in a pilot study in which respondents' survey answers were compared with their answers in a follow-up, face-to-face interview that included a careful examination of the respondents' understanding of the questions and response scales (

6).

The relationships between service satisfaction and other self-report measures were examined using Spearman rank correlation and the default statistical tests for zero correlation in SAS Proc Corr.

Results

Survey instruments were sent to 2,520 persons and were returned by 815 (32.3 percent). The mean±SD age of survey respondents was 37±11.4 years, and 586 (71.9 percent) of the survey respondents were female. Nearly half of the respondents (N=365) resided in a rural county. More than 75 percent of the respondents (N=610) completed high school or had an equivalent education level, and 38.9 percent (N=314) reported at least some college education. Nearly all of the respondents (709 respondents, or 88.5 percent) were white and of non-Hispanic descent. Only 167 respondents (20.6 percent) were married or living with a partner at the time of the survey; 318 respondents (39.3 percent) reported that they had never been married.

A total of 330 respondents (40.5 percent) had schizophrenia, 257 (31.5 percent) had an affective disorder, 93 (11.4 percent) had an anxiety disorder, and 135 (16.6 percent) had an adjustment disorder.

The response bias was evaluated and reported in a separate study (

7). Although some differences were noted between the group that responded and the group that did not, and the large size of each group made even small differences statistically significant, no response bias was apparent in demographic characteristics, utilization of mental health care, and primary diagnosis.

The mean ratings of service satisfaction for persons with and without schizophrenia were compared using a two-tailed t test for independent samples. The mean service satisfaction score of respondents with schizophrenia was .74, compared with .70 for the other diagnostic groups combined (t=2.60, df=722, p<.01). The mean life satisfaction scores for the groups were .68 and .58, respectively (t=5.04, df=661, p<.001). The mean mental health rating was 2.8 for persons with schizophrenia and 2.5 for those without schizophrenia.

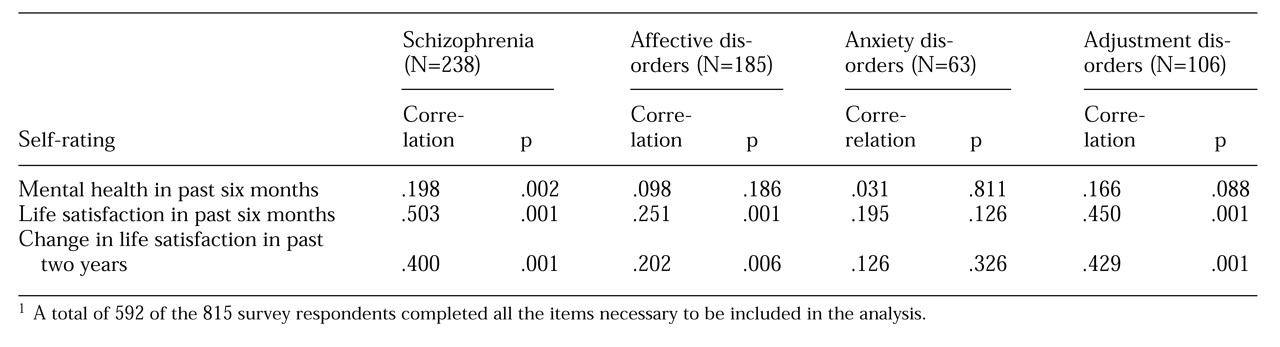

Spearman rank correlation coefficients between service satisfaction and other self-ratings were calculated for all diagnostic groups and are summarized in

Table 1. Among persons with schizophrenia, service satisfaction was most highly correlated with current life satisfaction. A statistically significant correlation was also noted for persons with affective disorder and adjustment disorder, but not for those with anxiety disorder. Service satisfaction was correlated with self-rated mental health status among persons with schizophrenia but not among those with affective or anxiety disorders. The correlation observed for respondents with an adjustment disorder approached statistical significance.

Change in life satisfaction was significantly correlated with service satisfaction for patients with adjustment disorder, schizophrenia, and affective disorder, although the relationship was much weaker for patients with affective disorder.

Discussion and conclusions

The relationship between service satisfaction, satisfaction with mental health, and life satisfaction was different for patients with different diagnoses. Additional research is needed to clarify the relationship between service satisfaction and self-reported health status measures among persons receiving services for different conditions, particularly when service satisfaction is used as a measure of program performance.

Service satisfaction, while important, may not be a valid measure of service adequacy among persons who have cognitive impairment as a consequence of mental illness (

8,

9). Patients with schizophrenia may be too generous in their assessments about the adequacy of care received, while patients with anxiety disorders may have a tendency to be negative. For patients with adjustment disorders, the observed correlation between service and life satisfaction may reflect general satisfaction after the resolution of an acute stressor.

Demographic characteristics explained only 7 percent of the variance in service satisfaction ratings in this survey of Medicaid recipients (data not shown). Earlier studies have not demonstrated a consistent effect of age, education, family size, income, marital status, occupation, race, religion, gender, social class, or diagnosis on satisfaction with mental health services (

4,

10). In a household survey of 400 persons, Weiss (

2) found that confidence in the community medical care system, having a regular source of care, and satisfaction with life in general were more important predictors of patients' satisfaction with primary medical care than age, gender, race, educational attainment, or income.

A limitation of the study reported here is the possibility of bias introduced by the large proportion of nonresponders. The extent to which these study findings can be generalized to all Medicaid recipients is unknown. Correlated measurement error may also have affected some of the observed correlations. That is, different questions may have been answered in the same way because the same response scale with similar wording was used.

In addition, the observed correlation between all of these scales could also be the result of a relationship with a common underlying dimension such as psychological well-being, contentedness, happiness, or positive attitude. Because these concepts may have little or nothing to do with the desired clinical benefit of a service, the common use of service satisfaction as a quality performance indicator should be interpreted with caution until further study clarifies its meaning and its relationship with other outcome measures.