The number of inpatient psychiatric beds has decreased sharply over the past generation, both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of total hospital beds. In the United States, bed reductions initiated in an era of deinstitutionalization have been fostered by the development of managed care. In Europe and other regions, the number of beds has decreased as a result of intense government pressure to curtail health care budgets. The health consequences of this dramatic reduction in inpatient psychiatric beds are not clear.

This report uses the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) dataset to examine the relationship between psychiatric beds per capita and annual death rates reported for persons with mental and substance use disorders (categories 290 to 319 in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision). Data reported to central government statistical agencies in seven countries between 1960 and 1996 were examined. Bed counts consisted of the average daily census or midyear count of available beds allocated for psychiatric treatment in all general or specialty inpatient or acute care institutions.

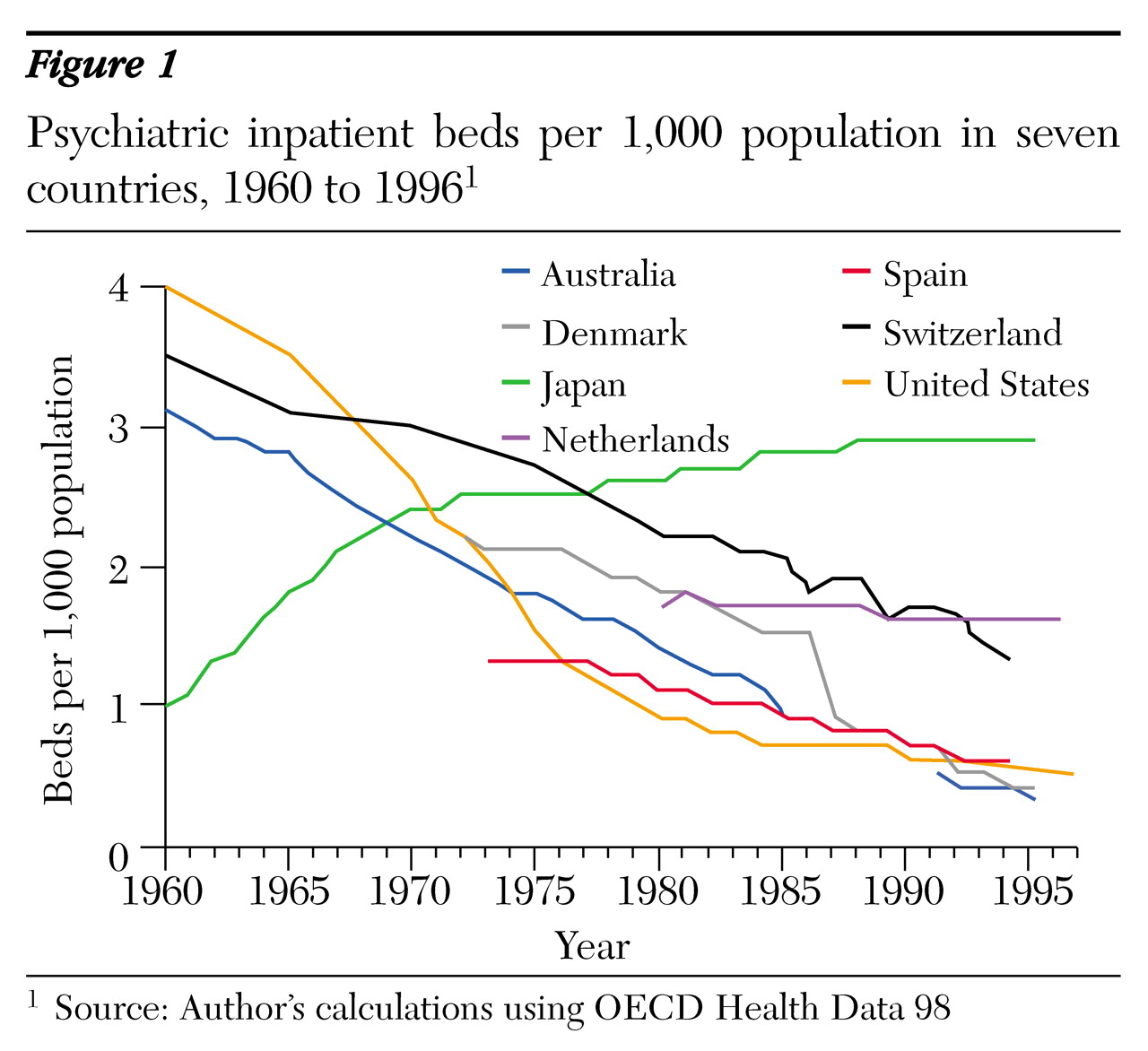

Figure 1 shows the total number of inpatient psychiatric beds per 1,000 population in the seven countries over the past three decades. In the U.S. beds dropped by two-thirds, from four per 1,000 population in 1960 to 1.3 per 1,000 population in 1994. In Australia the reduction was more remarkable, with a tenfold decrease from 3.1 per 1,000 in 1960 to .3 per 1,000 in 1995. In Japan beds increased from one per 1,000 population in 1960 to 2.9 per 1,000 in 1995.

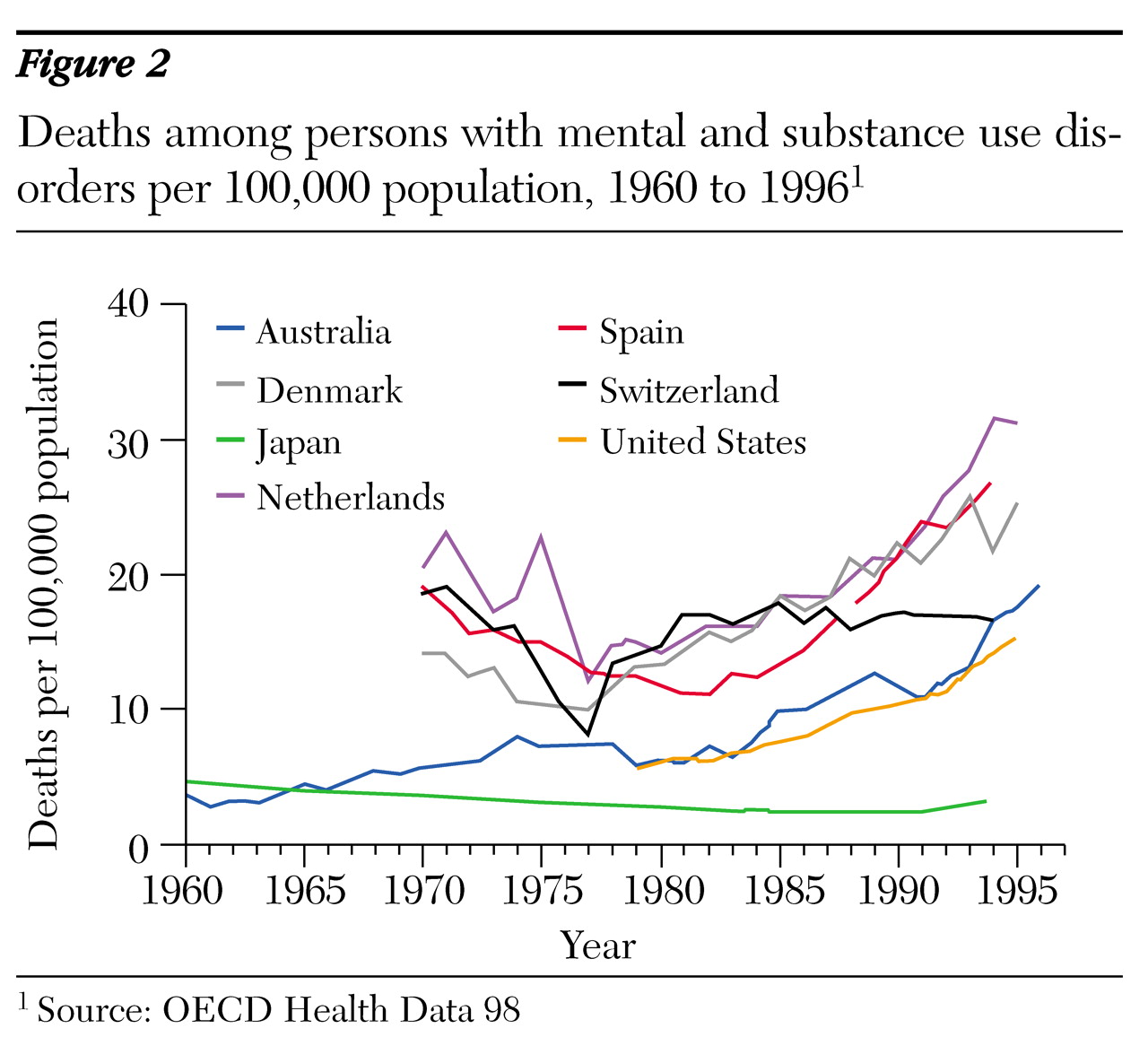

Figure 2 shows annual mortality per 100,000 population for persons with mental disorders. In six of the seven countries, the mortality rate has risen substantially. In the U.S. death rates have almost tripled, rising from 5.7 per 100,000 in 1979 to 15.5 per 100,000 in 1995. Death rates in Australia rose fivefold from 1960 to 1996, from 3.4 to 19.4 per 100,000 population. Japan witnessed a modest decline, with the number of deaths decreasing from 3.4 per 100,000 in 1970 to 2.8 per 100,000 in 1994.

Numerous other factors may be driving increased mortality among persons with mental and substance use disorders. In the U.S. persons with serious mental illness often lead a marginal existence, with poor health habits, high rates of substance use, and little access to all forms of health care. Nonetheless, these findings suggest a possible association between psychiatric bed reductions and increased mortality among persons with mental and substance use disorders.