It has been almost 50 years since antipsychotic medications were first introduced to the United States. Since that time we have witnessed extraordinary societal changes that probably could not have occurred in the absence of such drugs. It could be argued that many of these changes are the inevitable result of irreversible economic pressures and would have occurred even in the absence of antipsychotic medications. We will never truly know, but it is difficult to imagine the emergence of such trends without the antidelusional, antihallucinatory, antiagitation, and decibel-dampening effects of the antipsychotic drugs. The neighbors—collectively termed the community—would not have tolerated the noise.

The extent of these changes may be difficult to comprehend by those of us who missed the exhilarating experience of having lived in the B.C.—before chlorpromazine—psychiatric era and witnessed the introduction of antipsychotic drugs. The degree to which these medications have produced profound social and economic change is generally unappreciated and is best understood as a product of psychopharmacosocioeconomics—a useful, although personally constructed, neologism that addresses societal changes in relation to drug development.

Within this context, one of the major consequences of the introduction of antipsychotic drugs was the depopulation of state hospitals and the transfer of many patients to specialized living facilities in the community. These facilities are variously known as board-and-care homes, adult residential facilities, adult foster homes, adult homes, group homes, domiciliary homes, rest homes, personal care homes, family care homes, residential care facilities, and special hotels. In addition, a certain proportion of patients improved sufficiently so that they could return to their own homes.

This increase in the population of nonhospitalized patients with chronic schizophrenia created an enormous new consumer market, which provided an economic incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs that could work more effectively than the conventional antipsychotics and without troublesome side effects such as drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia. The new drugs, in the spirit of NASA, were supposed to work "faster, better, and cheaper," but along the way it became clear that "cheaper" did not mean cheap.

Cheaper meant that because of the new medications, the patient's psychiatric status could improve and recurrent hospitalizations could be avoided, thereby saving society a vast sum of money. Many of us uncritically accepted these macroeconomic justifications for high prices and ignored the microeconomic consequences of price escalations—such as the consequences for a consumer when payment must be made on an out-of-pocket basis.

These new medications are sometimes referred to as new-generation antipsychotics or as atypical antipsychotics because they are different from conventional antipsychotics and work via different pharmacological mechanisms. However, the new drugs are also atypical because their prices are atypically high.

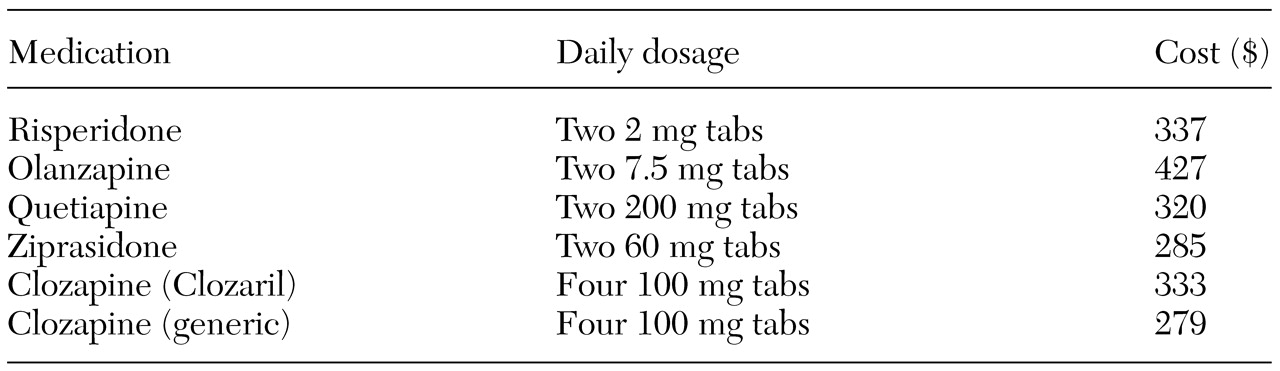

Table 1 lists the monthly costs for the five atypical antipsychotic medications in current use. The prices are based on the average wholesale price as listed in the

Drug Topics Red Book (

1) plus the retail markup of an average chain pharmacy. The prices represent the monthly cost of average therapeutic dosages for noninsured consumers in San Francisco. Noninsured consumers pay more for medications, because they do not enjoy the advantages of the lower prices afforded by bulk purchases—although such prices are not spectacularly lower.

It is undeniably true that these drugs are an improvement in many respects over conventional antipsychotics. By way of justifying the high costs of these new-generation medications, pharmaceutical manufacturers offered the quid pro quo argument that the high prices are justified (the quid) because they decrease the incidence of hospitalizations and thereby lower the costs of health care to society (the quo).

This quid pro quo pricing philosophy does not seem to have proportionately affected the pricing policies of new-generation medications used to treat other chronic diseases that cause multiple hospitalizations, such as the new oral antidiabetic drugs. A month's supply of metformin (Glucophage)—two 500 mg tabs a day—costs $37, approximately nine times less than most of the antipsychotics listed in

Table 1. It is interesting to speculate about what the cost of antibiotics might have been had quid pro quo pricing been used to justify their cost, given that the pricing policies would have had to reflect the value of preserving life.

However, unlike antibiotics, which are administered for several days or weeks, antipsychotics tend to be administered for a lifetime. What is unclear at this point is whether the savings associated with decreased hospitalizations have been offset by the increased costs associated with long-term daily use of atypical agents when extended over a lifetime. To estimate this cost in macroeconomic terms, one would have to consider not only the lifetime costs of the medication but also the difference in costs between a person who is dependent for a lifetime on tax revenue and a person who generates tax revenue for the better part of a lifetime.

In a sense, the atypical antipsychotic drugs have created a new type of addiction that is not amenable to treatment by conventional programs. In best-case scenarios, the addiction occurs among patients who have improved enough to resume a working career. However, they have become psychopharmacosocioeconomic addicts— "psychopharmaco" because they are dependent on the new medications for emotional stability; "economic" because once they have improved enough to live independently, they are unable to afford the drugs that induced the improvement; and "socio" because as a result of these factors they are locked into a social class that is dependent on government subsidies. Under such circumstances, best-case scenarios have become worst-case scenarios. I know of no good way to estimate the number of patients who are—or will be—in this position, but the probability is that for many patients the high cost of these medications will prevent their conversion from tax revenue recipients to employable tax revenue generators.

The macroeconomic costs of psychiatric medications are accelerating rapidly, as is evidenced by the following statistics obtained from the Medicaid program by the Lewin Group, a health and human services consulting firm, as part of a study of antipsychotic medications conducted under a contract with the National Institute of Mental Health (

2). Total costs for prescriptions for antipsychotic drugs grew from $484 million in 1995, to $641 million in 1996, to $894 million in 1997, and to $1.264 billion in 1998. The Lewin group interpreted the 1998 Medicaid costs for antipsychotic medications in the following way: Atypical antipsychotics account for the vast majority of expenditures on antipsychotics—in 1998, just over $1.1 billion, or 89 percent of expenditures. In 1998, 51 percent of the 11 million Medicaid prescriptions for antipsychotics were for atypical antipsychotics. In contrast, in 1995 atypical agents accounted for only 17.5 percent of the 9.1 million antipsychotic prescriptions for Medicaid beneficiaries. Only two new-generation atypicals were available in 1995 (clozapine and risperidone).

The Lewin Group also reported that the use of atypical antipsychotics in the Medicaid program has more than doubled since 1995 (

2). Concomitantly, the use of typical antipsychotics has dropped by 25 percent. In 1998 olanzapine accounted for the largest share of spending for antipsychotics—$536 million (42 percent). Risperidone ranked second at $395 million (31 percent), followed by clozapine at $172 million (14 percent). Oral haloperidol and phenothiazines accounted for only 2 percent and 6 percent of expenditures, respectively. Quetiapine accounted for only 2 percent of total antipsychotic expenditures, probably because in 1998 it was a newly marketed drug.

However, these medication costs are direct costs to the mentally ill population. In truth, we cannot attribute the high cost of the treatment of mental illness only to atypical agents. Pharmacological treatment of mental illness is now much more complicated than it used to be and involves psychiatric medications in addition to atypical antipsychotics. Stabilization of many patients depends on complicated pharmacological regimens that may include other antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants, minor tranquilizers, beta-blockers, antiparkinsonian agents, lithium, and stool softeners.

Furthermore, psychiatric patients are getting older, and they are not immune to the chronic physical illnesses that afflict older people without mental illness—diabetes, arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and other cardiovascular conditions. In one of the board-and-care homes that I visit, an audit of the medications revealed that in a total population of 28 patients, 23 patients were taking medications for the treatment of accompanying medical illnesses. Aspirin was not included in the audit. The average patient with mental illness is no longer a psychiatric patient in the sense of taking only psychiatric drugs. Perhaps a better term for the average psychiatric patient is simply "patient" or "broad-spectrum patient."

Other factors contribute to high costs. Hospitals are under increased pressure to discharge patients rapidly, and sometimes such discharges involve patients who are very disturbed. It often seems as if the number of medications that a patient is taking at discharge is inversely proportional to the duration of the hospitalization. Whatever the reason, patients are now being discharged on very complicated and very expensive drug regimens.

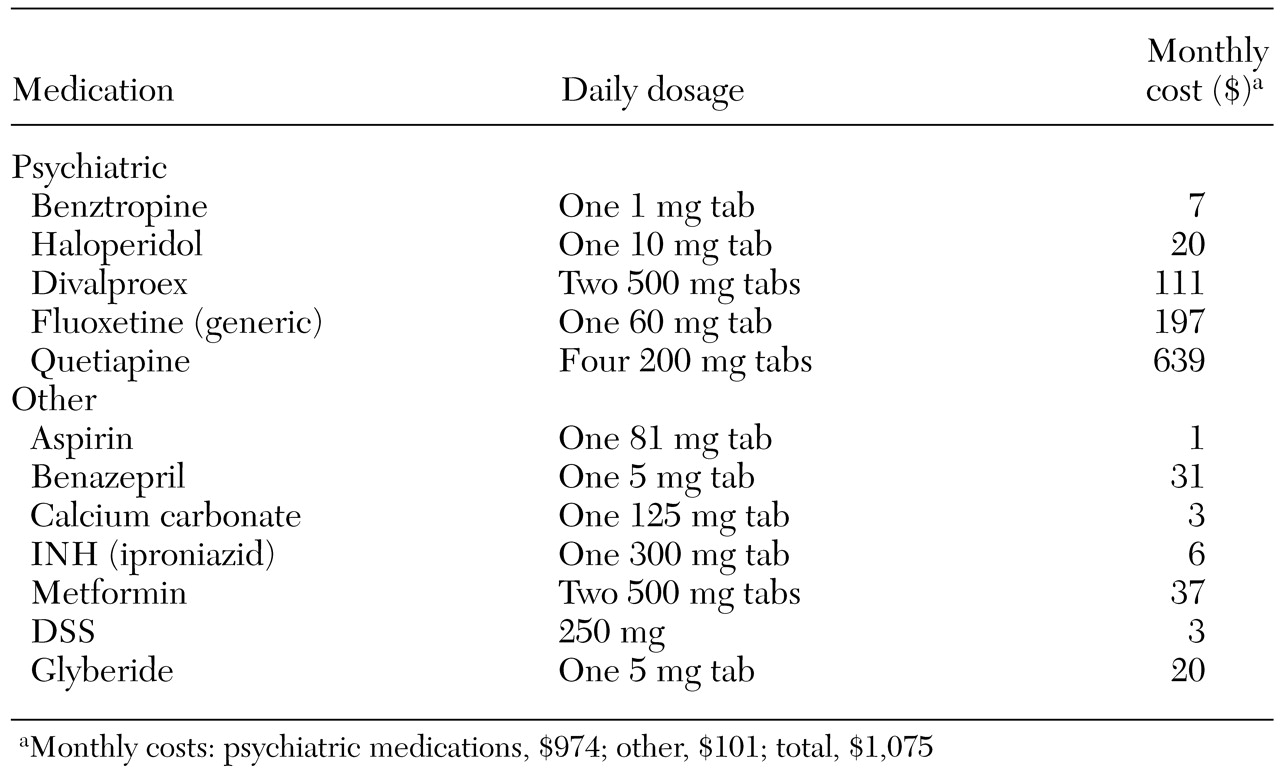

Table 2 summarizes the discharge order of a patient—patient A—released from a local hospital and admitted to a board-and-care home on May 9, 2002.

Of the drugs listed in

Table 2, four are for a psychiatric condition (haloperidol, divalproex, fluoxetine, and quetiapine), one is for the side effects produced by the psychiatric medications (benztropine), one is for the side effects of the medication used to treat the side effects of the psychiatric medications (DSS for constipation), and six are for the treatment of concurrent medical conditions (benazepril for hypertension, metformin and glyberide for diabetes, iproniazid for tuberculosis prophylaxis, calcium carbonate for osteoporosis prophylaxis, and aspirin for its preventive effect in cardiovascular diseases).

In this example, the cost of the nonpsychiatric medications is less than the cost of the psychiatric drugs, but this is not always true.

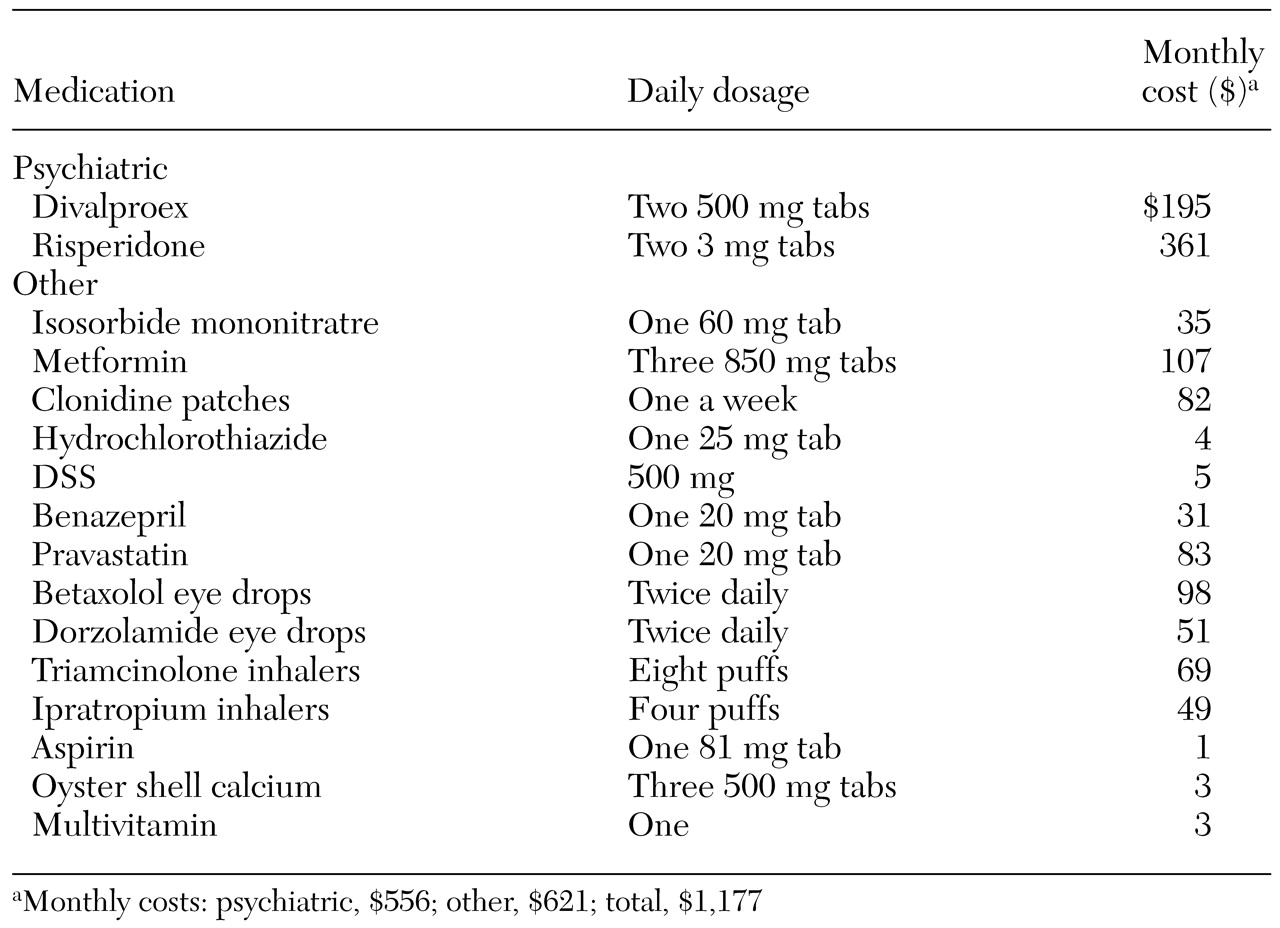

Table 3 shows the discharge order for a patient—patient B—with chronic schizophrenia and complications of asthma, diabetes, hypertension, glaucoma, and hypercholesterolemia, all of which may have been aggravated by the patient's history of smoking, alcoholism, and abuse of street drugs. This is an extreme example, but it provides an idea of what often happens to a somewhat lesser degree. Only two medications in the list (divalproex and risperidone) can be regarded as purely psychiatric.

What are some of the reasons for this increase in the complexity of medication regimens? Medications may be prescribed to prevent illnesses that have not yet occurred. Rapid hospital discharge policies may lead to shotgun treatments. Many clinicians adhere to the dictates of treatment algorithms of ever increasing complexity. Polypharmacy in the treatment of psychiatric and other chronic medical illnesses is becoming increasingly accepted. Also, unanticipated medical complications created by atypical antipsychotic medications must be treated, which include type 2 diabetes, weight gain, dyslipidemia, and, as some claim, osteoporosis.

No doubt there are other reasons, but regardless of the reasons, these regimens are much more expensive than they used to be. Since most of my practice involves the treatment of seriously mentally ill patients residing in board-and-care homes, many of whom have been recently discharged from hospitals, I am in a good position to identify emerging trends. My impression is that patients recently discharged from psychiatric hospitals are on drug regimens that are far more complex and far more expensive than the regimens of only two years ago. Patients recently discharged from hospitals to medical care facilities are like canaries in coal mines—they will be the first to show signs of an emerging medical trend that will affect all of medicine. The consequent increase in costs will eventually contribute to the economic difficulties of all mental health systems and inevitably of all health care systems.