Children were not spared from the September 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Eight children died on the airplanes that crashed into the World Trade Center and in the Pennsylvania countryside. Thousands of children were directly affected—by losing a parent or other family member, being displaced from their home, or being evacuated from their school. All told, 6,000 children experienced significant disruptions to their daily routines as a result of school closures (

1). A considerable number of children witnessed the events directly (

2), and countless more watched the replaying of dramatic footage in news broadcasts.

Although studies of the impact of trauma typically examine the effect on direct victims (

3,

4), the unprecedented magnitude of the September 11 attacks has led to concerns that the psychological sequelae will be substantial and enduring in the general population of New York City (

5). Studies suggest that the psychological sequelae among children is pronounced (

6,

7). Disaster mental health models emphasize the importance of early crisis intervention and supportive services (

8).

Although data on the effects of the September 11 attacks on adults' and children's mental health are being reported (

5,

6,

9), data on the use of services after the attacks are sparse. It is not known what effect parents' reactions to the September 11 attacks has had on children's mental health. This study, based on a survey of 112 Manhattan residents who were parents or primary caretakers, aimed to examine the exposure of a sample of children in Manhattan to the September 11 attacks, to describe the prevalence of child counseling, and to identify factors associated with whether children received counseling. This study has important implications, because parents play a central role in children's receipt of mental health services (

10).

Methods

Data collection

Data were collected through telephone interviews with a random sample of Manhattan residents between October 16 and November 15, 2001. The institutional review board at the New York Academy of Medicine approved the study, and all study participants provided informed consent. Interviewers were selected for the study on the basis of their experience working on other disaster studies. They were trained and monitored throughout the study. The interviews were conducted in English or Spanish.

A sample of households that had telephones and that were located below 110th Street in Manhattan were selected by using random digit dialing. An adult (defined as someone at least 18 years of age) in the household was randomly selected by using the last-birthday procedure. Adults who reported that they were the "parent" (defined as parent or primary caretaker) of a child living in the household were asked to respond to a set of questions about a focal child, who was also selected by using the last-birthday procedure. Of the 1,008 adults who completed the survey, 112 (11 percent) were the parents of at least one child living in the household.

Data from the 2000 census show that 17 percent of Manhattan households include a child or children under the age of 18 years. This survey undersampled households with children, because northern Manhattan neighborhoods have a higher proportion of households with children than neighborhoods below 110th Street. We excluded these neighborhoods because we were interested in surveying residents who lived in close proximity to the disaster site. The overall cooperation rate for the survey was 64.3 percent; the cooperation rate for parents was identical to the overall cooperation rate.

Instrument

The study participants provided information about the focal child's experiences immediately after the September 11 attacks on the basis of a structured questionnaire: where the child was at the time of the attacks, the location of the child's school or day care in relation to the World Trade Center, the amount of time before the child was reunited with a parent, whether the parent was concerned about the child's safety on September 11, whether the child saw the parent crying about the attacks, and whether the child knew a teacher or a coach who lost someone in the attacks. The parents were asked to estimate the average number of hours of television the child watched on September 11 and during the week after September 11. Information about the death of friends or relatives and loss of shelter, possessions, or the parent's employment was ascertained for the child on the basis of the parent's own reported disaster event experiences. Demographic characteristics of the children were also obtained from the parents.

We used a broad definition of counseling. The question asked was "Did the child receive any counseling related to his or her experiences from the September 11 attacks?" In a follow-up question, we asked who provided these counseling services—for example, a teacher or a psychiatrist—to determine whether the services were provided in school or by the mental health care system.

The parents were asked three questions about their child's behavior in the previous month: whether it was often true, sometimes true, or never true that the focal child did not get along with other children, could not concentrate or pay attention for long, or had been unhappy, sad, or depressed since September 11. The parents were also asked whether the focal child was covered under any health insurance.

We used three measures of parental mental health status: current posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to the disaster, recent depression, and panic attack during and immediately after the events of September 11. We measured current PTSD by using a modified version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) based on

DSM-IV criteria. This instrument has a coefficient of agreement with clinician-administered structured clinical interviews of .71 (

11,

12).

First, we measured current PTSD on the basis of the prevalence of criteria B, C, and D symptoms (necessary for the diagnosis of PTSD) in the previous 30 days. Second, for PTSD to qualify as current PTSD related to the September 11 attacks, at least one reexperiencing symptom (criterion B) and at least three content-specific avoidance symptoms (criterion C) had to be related to the September 11 attacks. Recent depression (in the previous 30 days) was assessed with a modified version of questions related to a major depressive episode from the Structured Clinician Interview for DSM-IV (

13,

14). Panic attack was measured with a modified version of the DIS for panic attack, phrased to assess symptoms that occurred in the first few hours after the September 11 attacks (

15).

Statistical analyses

Variables for the child's demographic characteristics and behaviors, disaster event experiences, and parents' mental health were cross-tabulated by the child counseling variable. Crude odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals were calculated for all bivariate associations. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of counseling related to the September 11 attacks. The final model included all the independent variables that were shown in the bivariate analysis to be associated with counseling at a significance level of less than .1.

Results

Sample description

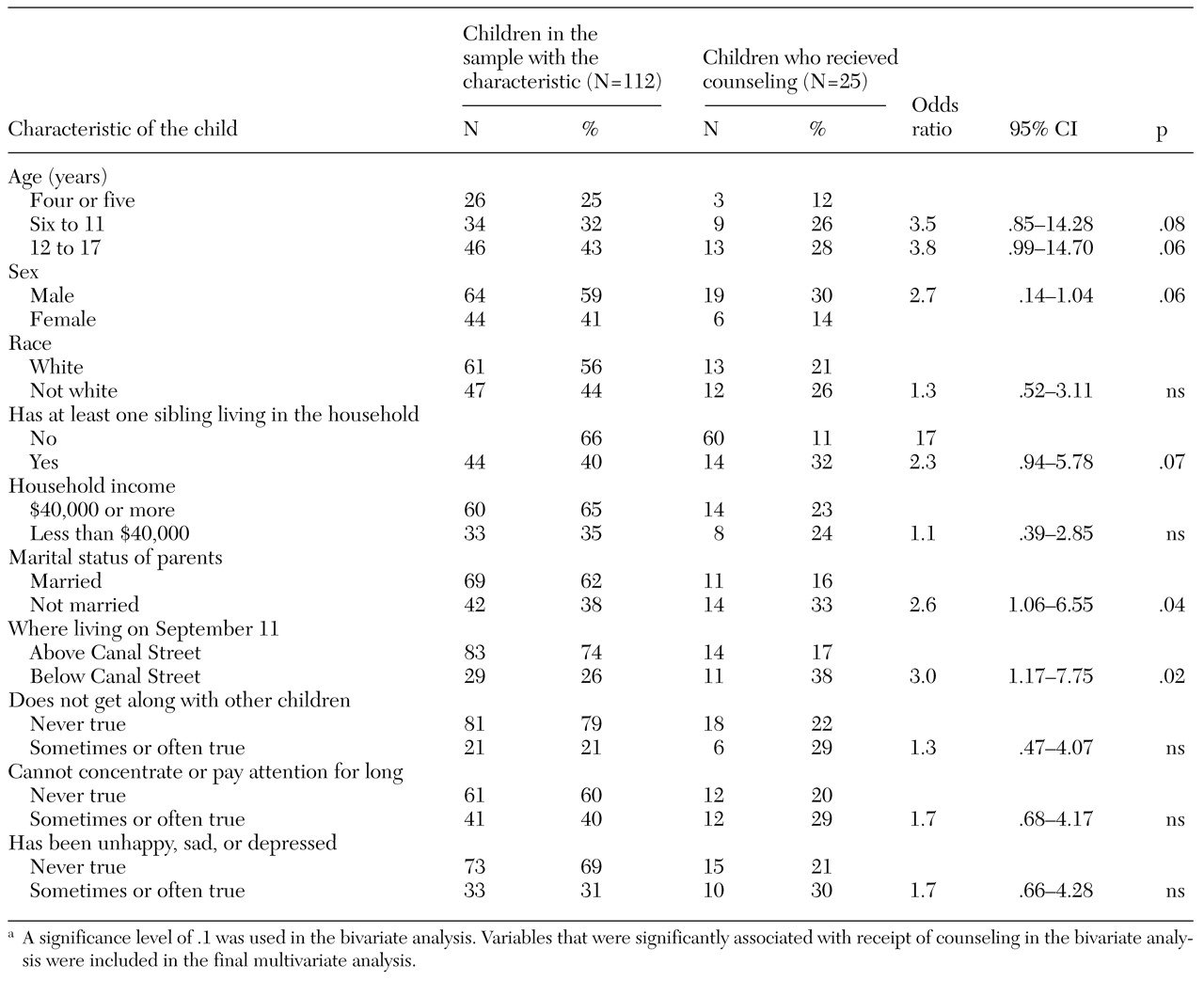

Among the 1,008 adults surveyed, 112 reported that they were the parent of at least one child who was living in their household. The bivariate relationships between child characteristics and receipt of counseling are summarized in

Table 1. Overall, 25 percent of the focal children were four or five years old, 32 percent were six to 11 years old, and 43 percent were 12 to 17 years old. Fifty-nine percent of the children were boys, 40 percent had at least one sibling living in the household, 35 percent lived in a household that had a reported annual income of less than $40,000, and 38 percent lived in a household with a parent who was not married.

Overall, 44 percent of the parents reported that they were not white—that is, that they were Spanish or Hispanic; Arab, North African, or Middle Eastern; Asian; black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or other. Twenty-six percent of the parents reported that they and the focal child were living below Canal Street, which is in close proximity to the disaster site, on September 11. On the behavior variables, 21 percent of the parents reported that it was sometimes or often true that their child had not gotten along with other children since September 11, 40 percent said that it was sometimes or often true that their child could not concentrate or pay attention for long, and 31 percent reported that it was sometimes or often true that their child had been unhappy, sad, or depressed since September 11. Only one child was reported not to have any health insurance coverage (data not shown).

Prevalence of counseling

Of the parents surveyed, 25 (22 percent) reported that the focal child had received some form of counseling directly related to his or her experiences on September 11. For 58 percent of the children this counseling was provided at school either by teachers (37 children, or 33 percent) or by a school psychologist (28 children, or 25 percent). Counseling was also provided in the health care system by psychologists or psychiatrists (24 children, or 21 percent) or by social workers (24 children, or 21 percent) (data not shown).

Children's disaster event experiences

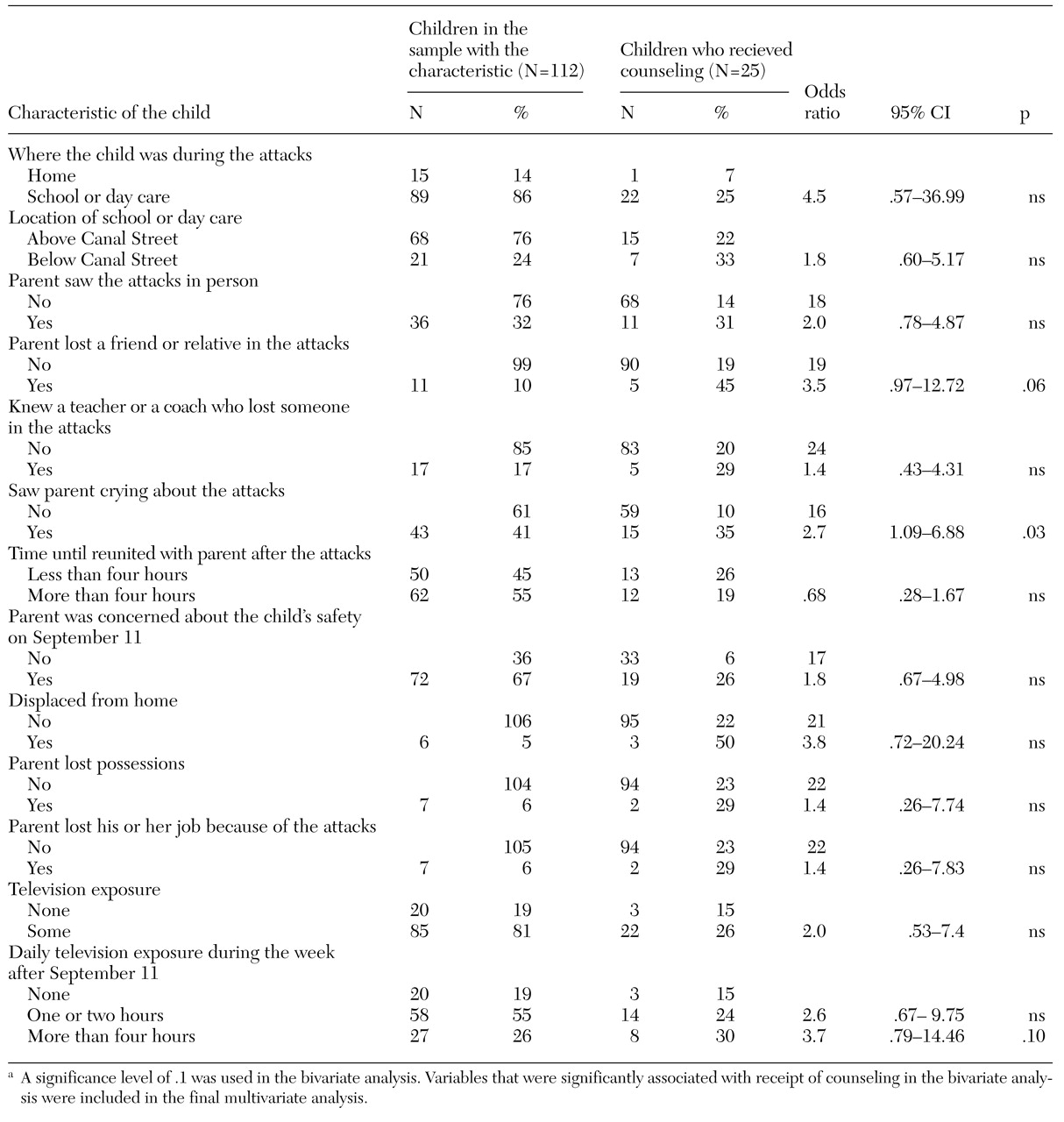

The bivariate relationships between the children's disaster event experiences and receipt of counseling are summarized in

Table 2. Eighty-six percent of the parents reported that their child was at school or day care during the events of September 11, and 24 percent reported that their child's school was located below Canal Street. About a third of the parents (32 percent) reported that they had seen some aspect of the disaster themselves, 10 percent said that a relative or friend had been killed, and 17 percent reported that the focal child knew a teacher or coach who had lost someone in the attacks. A majority of the parents (67 percent) indicated that they had been concerned about their child's safety on September 11; 55 percent said more than four hours passed before they were reunited with their child on that day. Forty-one percent said that their child saw them crying about the terrorist attacks. Five percent of the parents reported that they had been displaced from their home, 6 percent said that they had lost possessions, and 6 percent said that they had lost a job as a direct result of the attacks. Most parents (81 percent) said they believed that their child was exposed to some television coverage of the attacks either on September 11 or during the week after September 11, and 26 percent said that this exposure was likely to have been for more than four hours a day during the week after the attacks.

Parent's mental health problems since the attacks

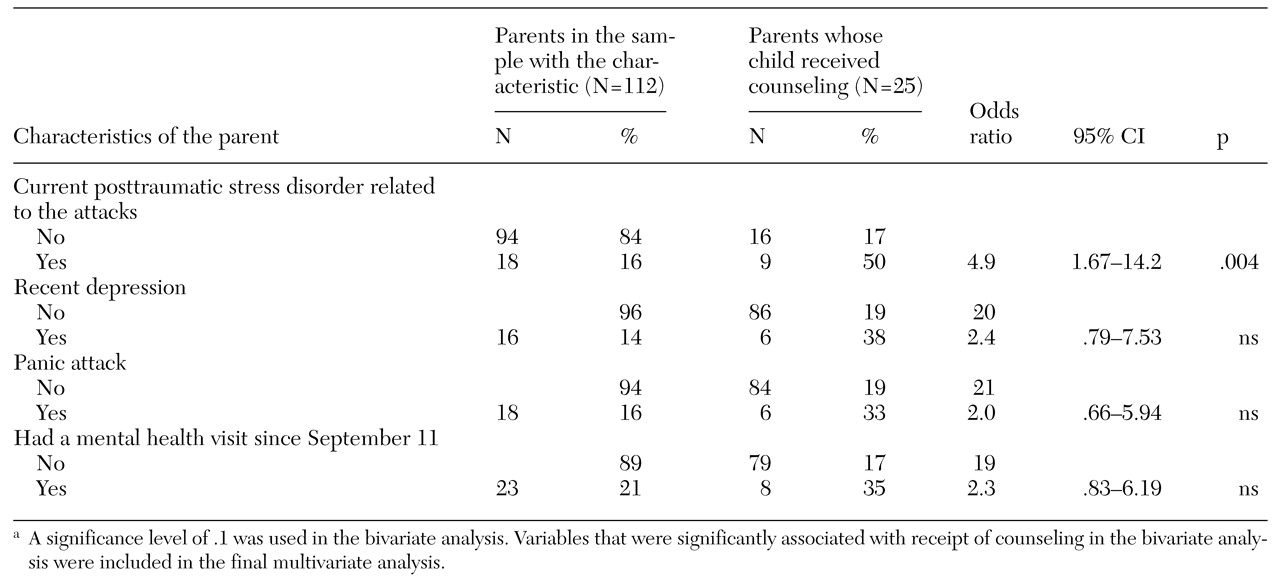

The bivariate relationships between characteristics of the parent and whether the child received counseling are summarized in

Table 3. The parents reported that they had experienced substantial mental health problems after the events of September 11. Sixteen percent had symptoms consistent with current PTSD related to the attacks, 14 percent had depression, and 16 percent had a panic attack during or shortly after the events of September 11. The prevalence of mental distress was greater among survey respondents who were parents than among those who were not; 7 percent of nonparents had current PTSD, 10 percent had current depression, and 12 percent had had a panic attack. However, these differences were statistically significant only in the case of current PTSD (p<.001) (data not shown).

About a fifth (21 percent) of parents said that they had made a mental health visit since September 11. The Spearman correlation coefficient between whether the parent received counseling and whether his or her child also received counseling was .12 (p=.002). The bivariate results indicated that parents who reported that they had cried about the attacks in front of their child were more likely to have had a mental health visit since the attacks than parents who had not cried in front of the child (p=.09).

Bivariate relations between covariates and counseling

Tables 1, 2, and 3 list covariates associated with receipt of counseling by the child. The child characteristics associated with receipt of counseling included age of six to 11 years (odds ratio=3.5 compared with age of four or five years), age of 12 to 17 years (OR=3.8 compared with age of four or five years), male sex (OR=2.7), having at least one sibling living in the household (OR=2.3), the parent's not being married (OR=2.6), and living below Canal Street (OR=3.0). The presence of behavioral problems was not significantly associated with whether the child received counseling. A chi square test of significance (data not shown) indicated that boys were more likely than girls to experience problems with peers (p=.10) and concentration difficulties (p=.03) but not sadness. Disaster event experiences associated with whether the child received counseling related to the September 11 attacks included the parent's having a friend or relative killed in the attacks (OR=3.5) and seeing the parent crying about the attacks (OR=2.7). Current parental PTSD associated with the attacks was also related to whether the child received counseling (OR=4.9).

Multivariate model predicting counseling

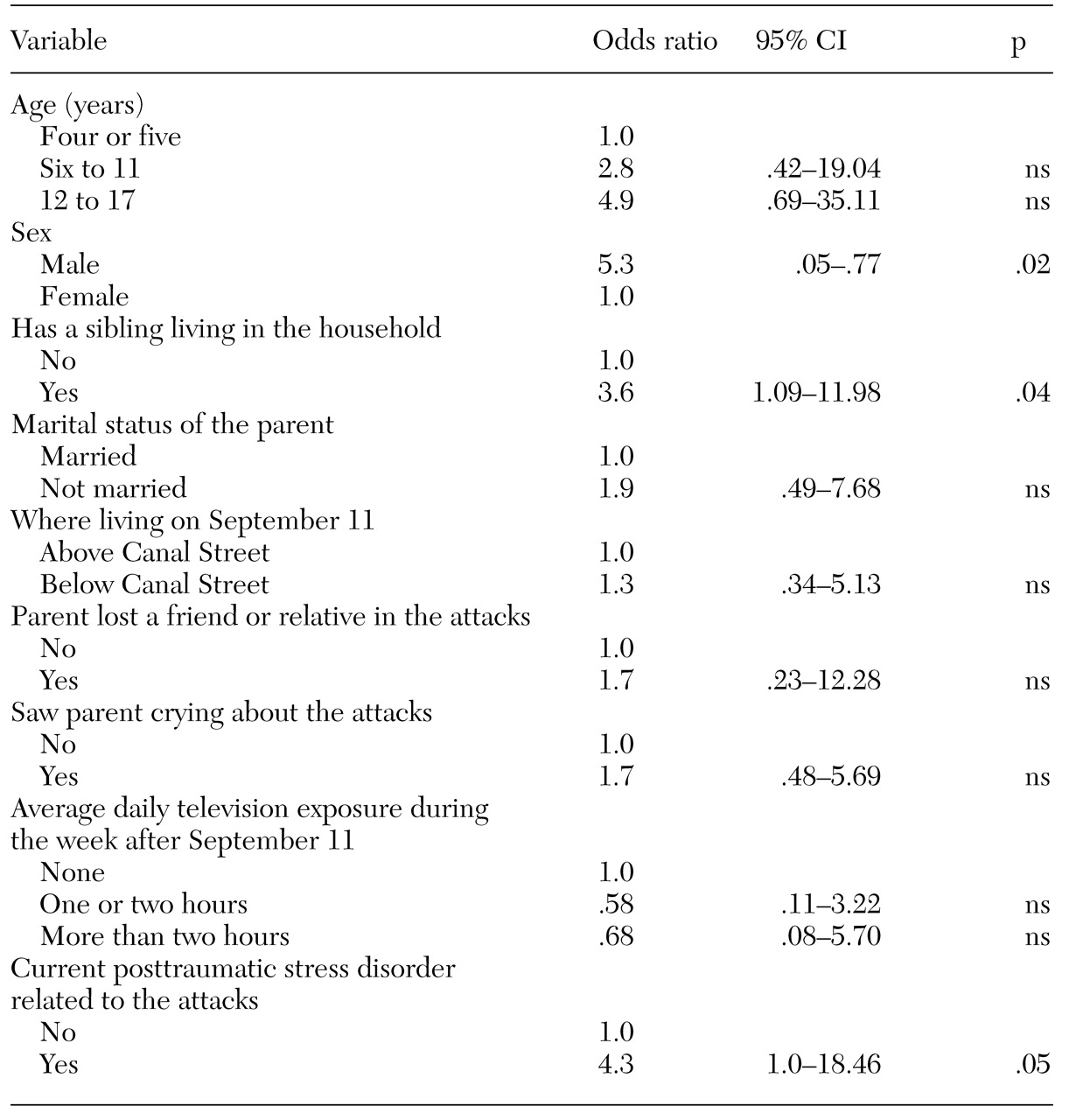

The results of the final multivariate logistic regression model are summarized in

Table 4. Male sex (OR=5.3), having at least one sibling living in the household (OR=3.6), and current parental PTSD (OR=4.3) were significant predictors of whether the child received counseling related to the September 11 attacks.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we found substantial levels of exposure to the September 11 attacks among children who lived in Manhattan below 110th street: 41 percent saw a parent crying about the attacks, 26 percent watched the event on television for more than four hours a day during the week after the disaster, and 32 percent had parents who witnessed the disaster in person. Moreover, 10 percent of the parents reported that a friend or relative had been killed, and 17 percent of the children knew a teacher or a coach who lost someone in the disaster. Twenty-two percent of the children had received some form of counseling related to the attacks. In a multivariate analysis, three factors were significantly associated with whether children received counseling: male sex, having a sibling in the household, and having a parent with PTSD related to the attacks.

The finding that almost a quarter of the children received some form of counseling is striking. Few studies have reported the prevalence of counseling for children after trauma. Studies that have been conducted have reported comparable rates of counseling for direct victims and far lower rates for children in the community at large (

16,

17). It is also pertinent that most of the counseling in this study (58 percent) occurred in the schools, as was the case after the Oklahoma City bombing (

18). Several New York City schools are currently providing counseling services to children (

19). Although counseling in a school setting might not be considered formal counseling, it is probably the norm for postdisaster situations, because formal disaster mental health services for children are commonly provided in schools (

20,

21).

The finding that boys were more likely than girls to receive counseling is puzzling. Most disaster studies of large samples have shown that girls are more symptomatic than boys (

22,

23,

24), although this is not a universal finding (

25,

26). Our finding may be related to parents' assessing symptoms among boys differently from those among girls. Maternal reports of a child's behavior tend to be biased in the direction of attributing more internalizing symptoms to girls and more externalizing symptoms to boys (

27). The higher prevalence of counseling among boys may reflect attention to more obvious externalizing symptoms and is consistent with the findings of other studies, such as studies of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (

28). In this study, we measured two externalizing symptoms: concentration difficulties and problems with peers. These symptoms were not associated with receipt of counseling in the bivariate analysis, but this finding does not preclude the possibility that other unmeasured externalizing behaviors identify boys more often than girls for counseling.

The children in this study who had at least one sibling in the household were more likely to have received counseling than the children who had no siblings. One possible explanation for this finding is that parents in households with multiple children may feel less able to cope with the emotional problems of their children as a result of greater demands on their time and attention.

The finding that parental PTSD was a significant predictor of whether the child received counseling is important, especially in light of the finding that the prevalence of current PTSD related to the September 11 attacks was twice as high among survey respondents who were parents or primary caretakers as among those who were not. Parental symptoms and poor parental functioning have been shown to constitute risk factors for development of symptoms among children after exposure to a disaster (

29,

30,

31,

32,

33).

These results are similar to those of studies conducted in other settings that have shown that parental attitudes, abilities, and well-being are important factors in whether children obtain health care (

34,

35,

36,

37). A growing body of evidence suggests that parental mental health is related to health care decisions made on the child's behalf (

35,

36). One important study found high levels of PTSD among injured children and their parents after automobile accidents and that the parents' symptoms affected decisions to provide appropriate care for their children as well as for themselves (

16). Mental health professionals should be aware of the link between parental mental health and the health care decisions that parents make on behalf of their children.

This study had several limitations. First, we did not obtain specific information about the types of counseling interventions provided, whether the counseling services were provided one-on-one or in a group, or how often these services were provided. Second, given that the literature indicates that parents underestimate the stress their children experience after traumatic experiences (

23,

37,

38), our results may underestimate children's behavioral reactions to the September 11 attacks. Third, because we sampled only households below 110th Street, our sample was relatively homogeneous compared with New York City overall. Fourth, we did not assess the children's behavior in school. One previous study indicated that disruptive behaviors in school are less common in the immediate aftermath of a disaster (

39). Finally, because of the small number of parents in the sample, there was insufficient statistical power to test some of the hypotheses, although many effects of this disaster were so large that even a sample of 112 parents was sufficient for differences to be detected.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study provided an early assessment of children's exposure to the September 11 attacks. It showed that children living below 110th Street in Manhattan were substantially exposed. Our results also suggest that there is a need for mental health professionals to be educated about the link between parental health and the decisions parents make about their children's needs for mental health services. More research is needed to ascertain the continuing mental health needs of children, the nature of the interventions being provided, and the effect on teachers of additional counseling responsibilities.