An estimated 25 percent of U.S. children are exposed to alcohol abuse or dependence in the family (

1). In the 1980s about 21 million adults in the United States grew up with an alcoholic parent (

2). As early as 1977, a lay movement to address this issue formally began when the first meeting of Adult Children of Alcoholics was convened to address the health and social problems of this population (

3,

4). Although self-help groups and publications subsequently flourished (

5), scientific investigation of the health and mental health problems of adult children of alcoholics has not kept pace with the development of lay recovery programs and literature (

6).

Children living in families with alcohol-abusing parents are more likely than other children to have an unpredictable home life and to carry a burden of secrecy as a result of their attempts to hide the alcohol abuse from others (

7,

8). These children also have an increased risk of a variety of other adverse childhood experiences, including being abused or neglected, witnessing domestic violence, and being exposed to drug-abusing, mentally ill, suicidal, or criminal household members (

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20).

The risk of alcoholism, psychopathology, and other medical and social problems has been reported to be greater among adult children of alcoholics than among other adults (

6,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25). However, little epidemiologic research has quantified the burden of the wide variety of adverse childhood experiences that are more common in alcoholic families and, in turn, the effect of this burden on the risk of alcoholism and depression among adult children of alcoholics.

To address these questions, we used data from more than 9,300 adults in a primary care setting who participated in the adverse childhood experiences study. First, we examined the association between growing up with one or more alcohol-abusing parents and nine adverse childhood experiences. Because previous research has largely ignored the co-occurrence of alcohol abuse in both parents (

20), we describe these associations according to whether the mother, the father, or both were alcohol abusers. Because the occurrence of alcoholism and depression may be influenced by both genetic predispositions (

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31) and environmental factors (

3,

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20), we assessed how adverse childhood experiences influenced the risk of alcoholism and depression among persons with and without a history of parental alcohol abuse.

Methods

Setting

The adverse childhood experiences study was based at Kaiser Permanente's San Diego Health Appraisal Clinic, where more than 50,000 adults receive standardized examinations annually. The health appraisals used at the clinic include completion of a standardized medical questionnaire, a physical examination, and review of laboratory results with the patient. All enrollees of the Kaiser Health Plan in San Diego are given literature about this free service. Most members are self-referred, and health care providers refer about 20 percent of the clinic's patients. A recent review of membership and utilization records among Kaiser members in San Diego who were continuously enrolled between 1992 and 1995 showed that 81 percent of those 25 years of age or older had been evaluated in the Health Appraisal Clinic during this four-year interval.

Procedures

The data reported here are from a retrospective cohort analysis of data from the larger study; the methods of the larger study have been reported in detail elsewhere (

9,

10). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group (Kaiser Permanente), the Emory University School of Medicine, and the Office of Protection from Research Risks of the National Institutes of Health.

A total of 13,494 Kaiser Health Plan members who completed standardized medical evaluations at the Health Appraisal Clinic between August 1995 and March 1996 were mailed the study questionnaire, which included questions about childhood abuse and exposure to forms of household dysfunction while growing up. Those who did not respond to the first mailing received a second mailing. The response rate for the survey was 70.5 percent (9,508 members).

We found no important differences between respondents and nonrespondents in health risk behaviors, such as smoking, obesity, and substance abuse, or in history of disease, such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Nonrespondents tended to be somewhat younger and to be from racial or ethnic minority groups. Furthermore, after adjustment for differences in age and race, the magnitude of the relationships between a history of sexual abuse and health behaviors and outcomes was nearly identical for respondents and for nonrespondents. Thus we found no evidence that response bias affected the direction or strength of our estimates of the association between a history of sexual abuse and behavioral and health outcomes (

32).

We excluded 51 respondents with missing information about race, 34 with missing educational data, and 77 with incomplete information about parental alcohol abuse. The final study cohort of 9,346 included 98 percent of the respondents.

Measures

Parental alcohol abuse. Questions about exposure to parental alcohol abuse during childhood were adapted from the supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey conducted by the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (

33). The specific question was "During your first 18 years of life, did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic?" Those who responded affirmatively were asked to check boxes from a list to indicate the identity of the alcohol abuser or abusers. Persons whose father, mother, or both were alcohol abusers were defined as adult children of alcoholics.

Adverse childhood experiences. Questions about adverse childhood experiences asked specifically about the respondent's first 18 years of life. The experiences were verbal abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, having a battered mother, parental separation or divorce, and four types of household dysfunction—exposure in the household to drug abuse, mental illness, suicide, or criminal behavior. Questions about verbal and physical abuse and about having a battered mother were adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (

34), for which the five possible responses were never, once or twice, sometimes, often, or very often. Questions about contact sexual abuse were adapted from Wyatt (

35). More information about the wording of specific questions for the nine adverse childhood experiences can be obtained from the authors or from previous publications of the adverse childhood experiences study (

9,

10).

For each respondent we summed the number of adverse childhood experiences to create an "ACE score," which ranged from 0 to 9. The ACE score has been shown to have a robust and graded relationship to unintended pregnancies (

36), sexually transmitted diseases (

37), numerous health risk factors such as smoking (

10), and many of the leading causes of death during adult life (

9).

Personal alcoholism and depression. A personal history of alcoholism was defined as an affirmative response to the screening question used in the NIAAA supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (

32), "Have you ever considered yourself to be an alcoholic?"

We used a screening instrument for depressive disorders—major depression and dysthymia—that was developed for the Medical Outcomes Study (

38,

39). This instrument used data from primary care and mental health subsamples of the Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey (

40) and the Psychiatric Screening Questionnaires for Primary Care Patients (

41).

The screening instrument includes two questions from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (

42): "In the past year, have you had two weeks or more during which you felt sad, blue, or depressed, or lost pleasure in things that you usually cared about or enjoyed?" and "Have you had two years or more in your life when you felt depressed or sad most days, even if you felt okay sometimes?" Respondents who answered yes were asked, "Have you felt depressed or sad much of the time in the past year?"

The instrument also included six questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (

43). The CES-D items ask the respondent how often in the past week the following statements were true: "I felt depressed." "My sleep was restless." "I enjoyed life." "I had crying spells." "I felt sad." "I felt that people disliked me." The response scale for these questions was less than one day, one or two days, three or four days, and five to seven days.

The prediction equation developed for this screening tool uses responses to the questions from the DIS and the CES-D; we used a cutoff score of .009 to define a lifetime history of depression (

39).

To assess recent problems with depressed affect, we also assessed the relationship of parental alcoholism and adverse childhood experiences to the first question from the DIS.

Statistical analysis

Persons who gave incomplete information about an adverse childhood experience were considered not to have had that experience. This approach would likely have resulted in conservative estimates of the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes, because some of those who had had the experience would have been misclassified as not having had it; this type of misclassification would have biased our results toward the null hypothesis (

44). However, to assess this potential effect, we repeated our analyses after excluding all respondents with missing information on any of the adverse childhood experiences. The results of this analysis did not differ substantially from the results we report here.

We calculated the adjusted odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals for the associations between parental alcohol abuse and each of the nine adverse childhood experiences by using logistic regression. Then we calculated the adjusted odds ratios for the relationships between the experiences and a personal history of alcoholism or depression. Next, we assessed the relationship of the ACE score to these two disorders using five dichotomous variables (ACE scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more); having had no adverse childhood experiences was used as the referent. To test for a trend, we entered the ACE score as an ordinal variable. We then assessed the relationships between parental alcohol abuse and the risk of alcoholism and depression during adulthood with and without control for the ACE score. We included age, sex, race, and education as covariates in all models. Finally, we assessed the prevalence of alcoholism and depression while we controlled simultaneously for the ACE score and for a history of parental alcohol abuse.

Results

The mean±SD age of respondents was 56.6±15.6 years (range, 19 to 94 years). Fifty-four percent (N=5,004) were women, and 79 percent (N=7,380) were white. Forty-two percent (N=3,930) were college graduates, and 7 percent (N=633) had not graduated from high school.

Parental alcohol abuse was reported by 20.3 percent of respondents (N=1,894): mother only (2.3 percent or 213 respondents), father only (15.2 percent or 1,417), and both parents (2.8 percent or 264). The prevalence of parental alcohol abuse declined with the age of the respondent and was higher among women (22.8 percent compared with 17.4 percent).

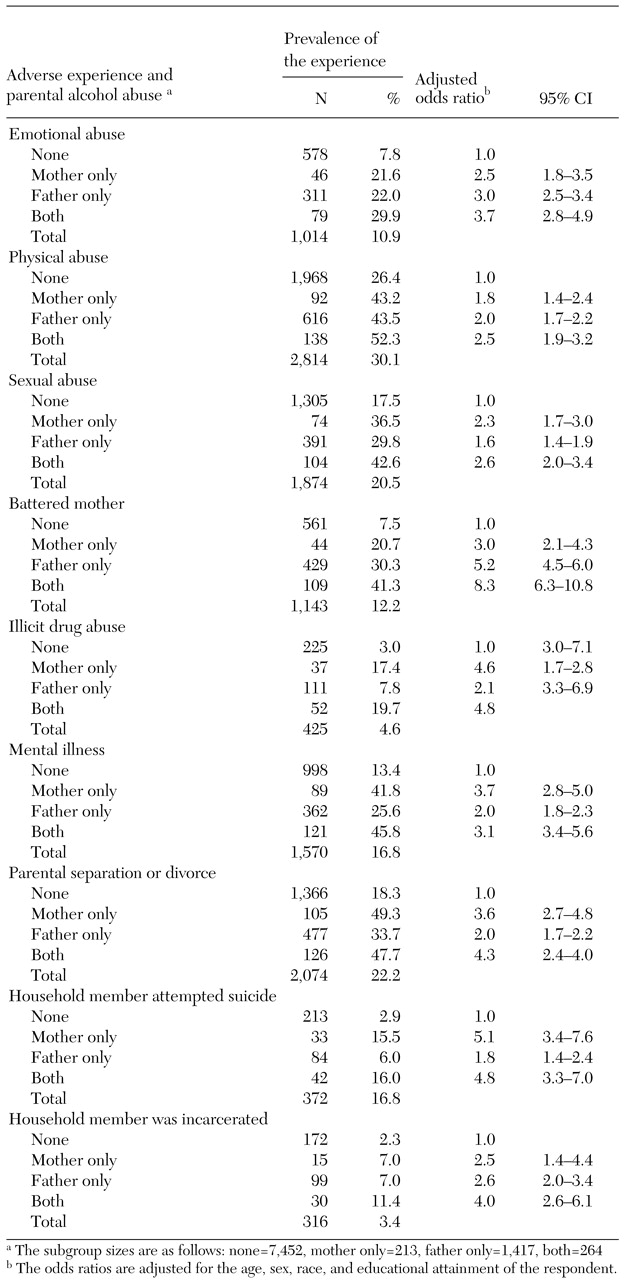

As

Table 1 shows, in contrast with respondents who reported no history of parental alcohol abuse, those who had grown up with at least one alcohol-abusing parent were two or three times as likely to report childhood histories of emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and parental separation or divorce. Respondents who reported a history of parental alcohol abuse were two to five times as likely to have lived during childhood with household members who used illicit drugs, had mental illnesses, attempted suicide, or were criminals (p<.001 for all associations). Respondents who reported parental alcohol abuse were three to eight times as likely to have had a battered mother as those with no history of parental alcohol abuse.

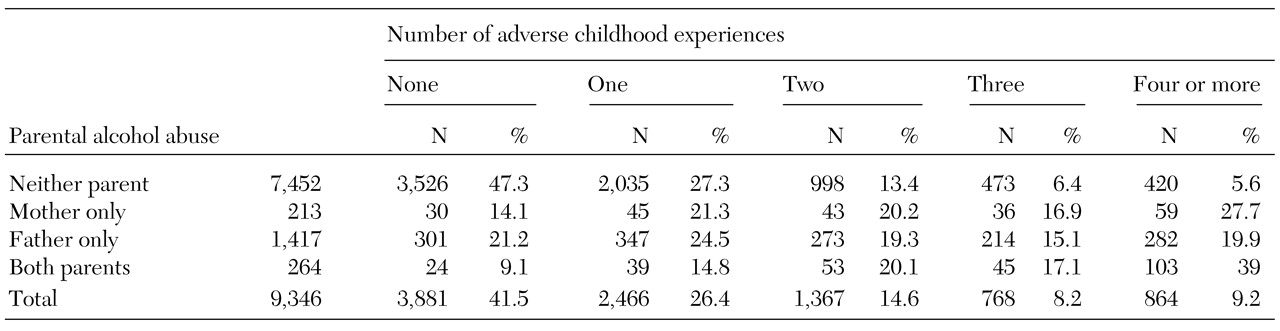

As shown in

Table 2, respondents with no history of parental alcohol abuse were less likely to report any of the nine adverse childhood experiences. Among respondents without a parental history of alcohol abuse, 47 percent had an ACE score of 0, compared with 9 percent of those who grew up with two alcohol-abusing parents. Six percent of the former group had an ACE score of 4 or more, compared with 39 percent of the latter group. After adjustment for age, race, sex, and education, the mean±SD ACE scores according to parental history of alcohol abuse were as follows: neither parent, 1.2±.04; mother only, 2.5±.10; father only, 2.1±.05; and both parents, 2.9±.09. Differences between all groups were statistically significant in the linear regression analysis (p<.001).

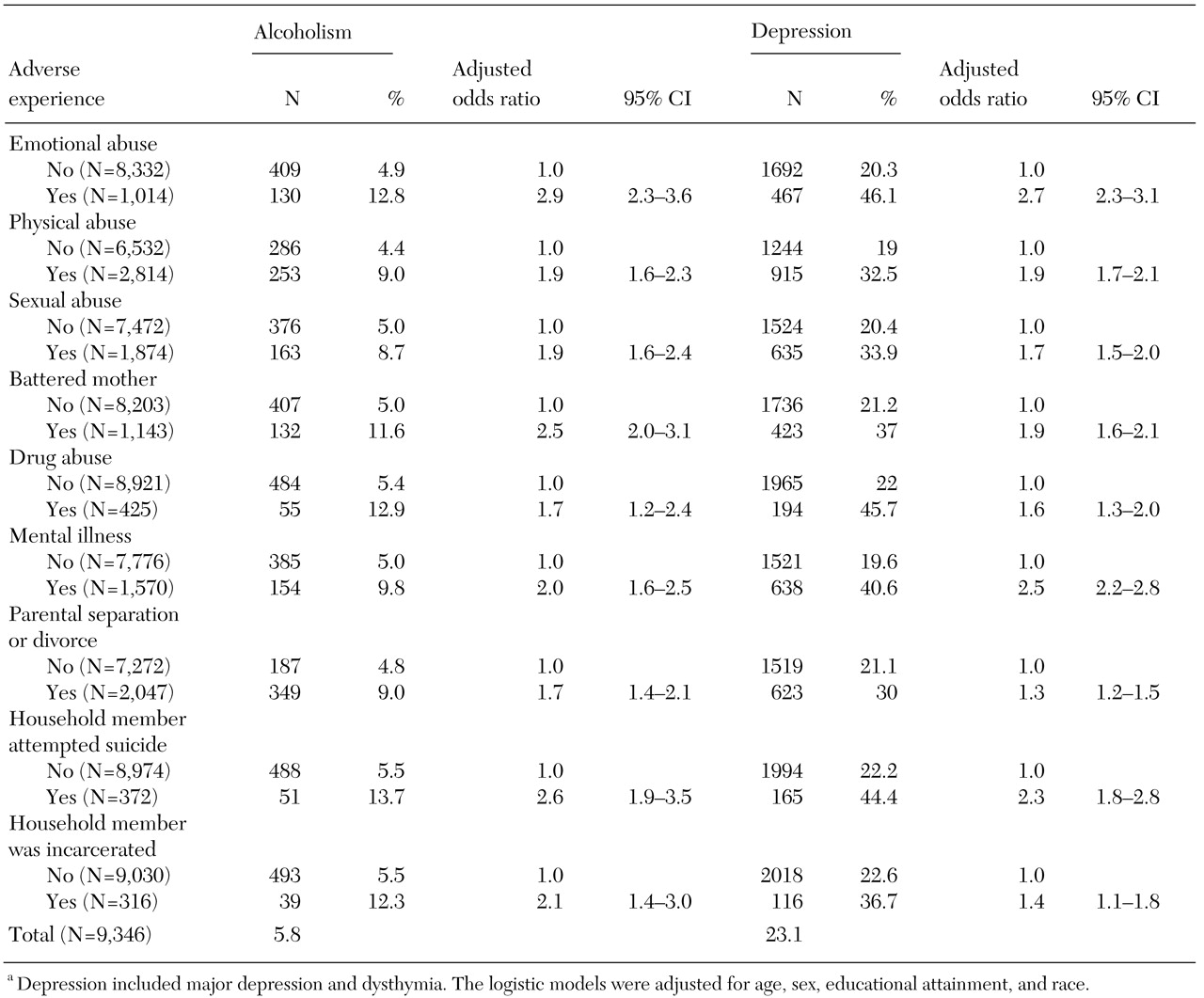

As can be seen in

Table 3, a personal history of alcoholism was reported by 5.8 percent of respondents (N=539), a lifetime history of depression was reported by 23.1 percent (N=2,159), and recent problems with depressed affect by 23.4 percent (N=2,184). Each of the nine adverse childhood experiences was associated with both personal alcoholism (p<.05), a lifetime history of depression (p<.05), and recent problems with depressed affect (p<.05).

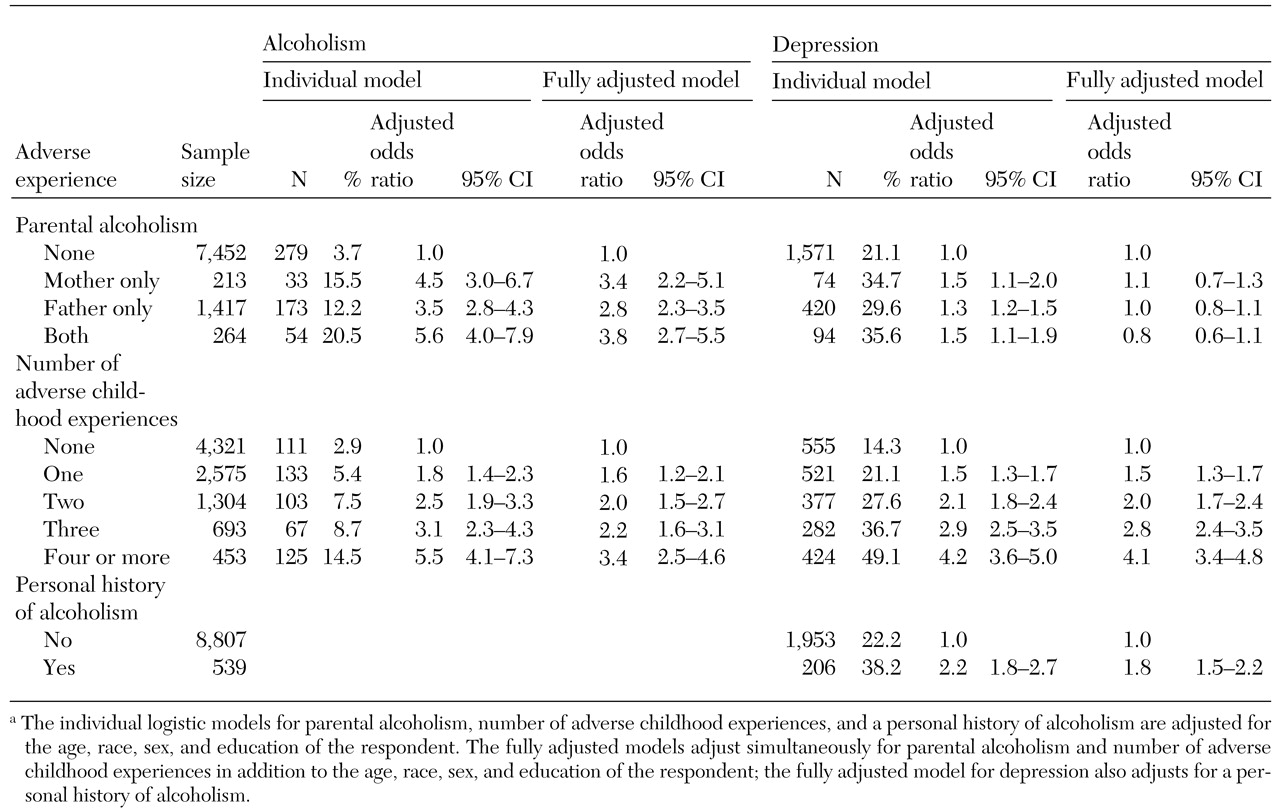

As shown in the individual models in

Table 4, a personal history of alcoholism was strongly related to having alcohol-abusing parents and to the number of adverse childhood experiences reported. We concluded that these two factors were independent, because each remained strongly associated with having a personal history of alcoholism after we simultaneously adjusted for both in the statistical model (fully adjusted model in

Table 4). Indeed, the overall fit of the logistic regression model in which only parental alcohol abuse was considered was significantly improved when the ACE score was added (χ

2=67, df=4, p<.001). This result suggests that the most accurate estimate of the relationship between having a personal history of alcoholism and either of these factors is obtained when both are accounted for simultaneously.

The individual model in

Table 4 suggests that parental alcohol abuse increased the risk of depression by 30 to 50 percent. However, having alcohol-abusing parents was not independently associated with a lifetime history of depression after we adjusted for the ACE score. The odds ratios for having alcohol-abusing parents were all near the null value of 1, whereas the odds ratios for the ACE score were strong and graded. Further evidence that adverse childhood experiences are important risk factors for depression comes from the finding that the fit of the model that included only parental alcohol abuse was dramatically improved with the addition of the ACE score (χ

2=2=447, df=4, p<.001). The addition of both the ACE score and a personal history of alcoholism did not improve the fit of the model (data not shown). The findings for depressed affect in the past year were nearly identical to those for a lifetime history of depression (data not shown).

Respondents with higher ACE scores were more likely to have a personal history of alcoholism. Furthermore, among respondents with similar ACE scores, the prevalence of alcoholism was substantially higher among those who had alcohol-abusing parents than among those who did not. We fit a generalized linear model with binomial errors and identity link to the prevalence data and found no evidence that parental alcohol abuse modified the relationship between ACE score and a personal history of alcoholism.

Although we found a strong, graded relationship between the ACE score and a lifetime history of depression, we did not find that depression was more prevalent among respondents who had alcohol-abusing parents. We fit a generalized linear model with binomial errors and identity link to the prevalence data and found no evidence that parental alcohol abuse modified the relationship between ACE score and current depression. The findings for the variable "depressed affect in the past year" were nearly identical to those for current depression.

Discussion

Growing up with alcohol-abusing parents substantially increased the risk of each of the nine adverse childhood experiences as well as the risk of multiple adverse experiences. We found an independent, graded relationship between the number of adverse childhood experiences reported and the risk of alcoholism and depression regardless of whether the respondent reported parental alcoholism. Although the prevalence of personal alcoholism was higher among respondents with a parental history of alcoholism, parental history did not affect the strength of the graded relationship between the ACE score and alcoholism. An important finding of this study is that depressive disorders among adult children of alcoholics appear to be largely, if not solely, due to the greater likelihood of having had adverse childhood experiences in a home with alcohol-abusing parents. Respondents who had similar ACE scores had a similar risk of depression—both lifetime and current—whether or not they had alcohol-abusing parents.

Other studies have shown that childhood trauma and familial and genetic factors are associated with alcoholism and other forms of substance abuse (

29,

45,

46,

47). Family studies have found that adult children of alcoholics are three or four times as likely to develop alcoholism as adults whose parents were not alcoholics (

29). Twin studies have found concordance rates of alcoholism of between 30 percent and 36 percent among fraternal twins and 60 percent among identical twins (

48). Similarly, adopted sons of alcoholic fathers have a higher risk of alcoholism than adopted sons of nonalcoholic fathers (

49).

The increased risk of alcoholism reported in these studies is consistent with our finding of a 3.5- to 5.6-fold risk of alcoholism among adult children of alcoholics regardless of the extent to which they had adverse childhood experiences. Previously published findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study have also shown that adults who reported four or more adverse childhood experiences were two to ten times as likely as adults who had no adverse childhood experiences to report other forms of substance abuse, including illegal drug use, parenteral drug abuse, and smoking (

9,

10). Another area of research that is still in its infancy has identified physiologic and biochemical markers of familial transmission of alcoholism (

29,

50,

51).

The aggregation of alcoholism and depressive disorders in families has been observed (

52,

53), but its underlying mechanism is unclear. We found that depressive disorders were 30 percent to 50 percent more common among adult children of alcoholics, a finding consistent with a previous report (

54). However, we also observed that parental alcoholism was not independently related to lifetime risk of current depression after we simultaneously controlled for adverse childhood experiences and a personal history of alcoholism. Furthermore, we found no evidence that adverse childhood experiences and parental alcoholism interact to increase the risk of depression. Rather, the increased risk of depression among adult children of alcoholics appears to have been determined by the extent of childhood trauma, such as abuse, domestic violence, and other family dysfunction, that we found to be substantially more common in alcoholic households.

Our results corroborate previous findings suggesting that traumatic childhood experiences are an important component in the etiology of alcoholism and depression (

29,

47,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67). Understanding that the origins of depression among adult children of alcoholics may be the result of the trauma of child abuse, domestic violence, and other family dysfunction could be critical to the diagnosis and treatment of depression in this group (

9,

47,

67).

Adverse childhood experiences such as sexual abuse have been shown to be underreported (

68,

69). Furthermore, our measure of personal alcoholism likely resulted in substantial underreporting of a personal history of alcoholism. These forms of underreporting probably would have biased our results toward the null hypothesis, and thus our estimates of the association between adverse childhood experiences and both depression and alcoholism are probably conservative.

Our study showed that the risk of mental illness, drug abuse, and suicide attempts in the household was strongest when the mother was an alcoholic and that the risk did not significantly increase when both parents were alcoholics. The pivotal role of an alcoholic mother in the emergence of household dysfunction may stem from the fact that the mother is generally the primary caretaker. Alcohol abuse may diminish a mother's capacity to care for her children and to deal with household problems. In addition, women who abuse alcohol are more likely to marry chemically dependent men (

70). An alcoholic mother's difficulty in caring for her children may be exacerbated by the coexistence of affective, personality, and thought disorders (

53).

Our findings suggest that prevention of child abuse, domestic violence, and other forms of household dysfunction that are common in alcoholic families will depend on advances in the identification and treatment of alcoholic parents (

4,

6,

7,

54). Improved recognition and treatment of alcoholism in adults and tandem family interventions to reduce the burden of adverse childhood experiences in alcoholic households (

9,

10) would probably decrease the long-term risk of alcoholism, depression, and other adverse effects of trauma observed among adult children of alcoholics (

54,

71,

72,

73,

74). Alcohol treatment programs and child protective and welfare services have tended to ignore the likelihood that they share a population of clients (

1,

47). The tendency is probably even more pronounced in primary care settings, where despite guidelines established by the American Medical Association (

75,

76,

77), clinicians' inquiries about issues such as domestic violence are infrequent (

47,

78,

79,

80).

Health care providers need training and guidelines not only for identifying and treating families in which children are exposed to adverse experiences but also for identifying and treating adult children of alcoholics (

81,

82,

83). Our data strongly suggest that prevention and treatment of alcohol abuse and depression, especially among adult children of alcoholics, will depend on clinicians' inquiring about parental alcohol abuse and the long-term effects of adverse childhood experiences, with which both alcohol abuse and depression are strongly associated.