Methods

Data for psychiatrists in California who participated in the 1998 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP) were used in this study. The 1998 NSPP was the second in a series of nationwide surveys conducted by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to measure a range of clinical, organizational, and financing characteristics that shape contemporary psychiatric practice (

21,

23). The APA membership database, which is considered to represent a majority of practicing psychiatrists in the United States, was used in the sampling frame for the study. The 26-item survey was implemented through a series of personalized mailings, reminder postcards, and telephone calls.

Systematic sampling procedures were first used to select 1,200 participants. In addition, a random sample of 100 psychiatrists was drawn from each of three subgroups: African Americans, Hispanics, and psychiatrists younger than 40 years. The final sample of 1,500 psychiatrists represented the APA membership across key demographic and training variables. To adjust for the oversampling of psychiatrists from these three subgroups, a correction weight was constructed on the basis of a series of logistic regression models. A total of 1,076 valid surveys were received, for a response rate of 72 percent. Additional information about the sampling procedures, field methods, and weighting scheme as well as a description of the survey have been reported previously (

21).

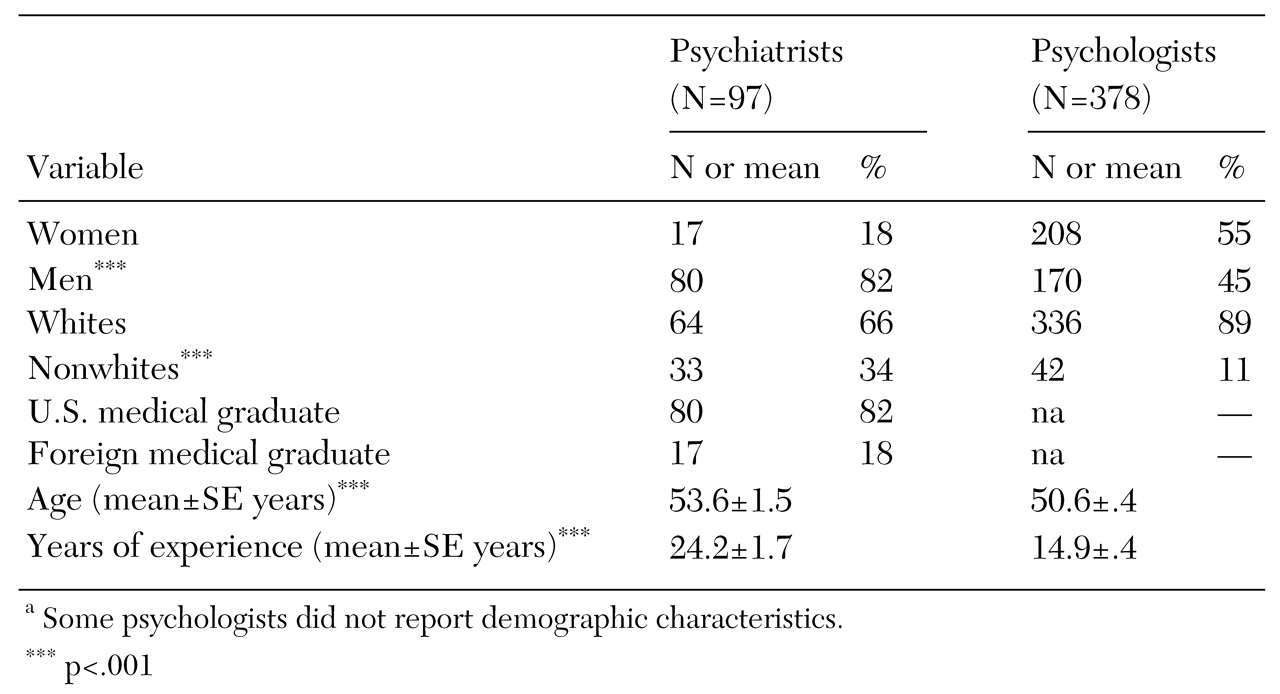

The 97 California psychiatrists represented nearly 10 percent of the 1998 NSPP sample. Preliminary comparisons of selected variables were made between the study sample and the larger 1998 NSPP sample. The subsample of NSPP psychiatrists in California was similar to the entire 1998 NSPP sample in age, mean number of years of clinical experience, and ethnicity but overrepresented male psychiatrists. The study sample was also similar to the 1998 NSPP sample in the proportion of psychiatrists who provided long-term psychotherapy, the proportion of psychiatrists who provided medication services without psychotherapy, and the mean rate of participation in managed health care plans.

The study sample reported a greater mean number of weekly hours in solo practice than the 1998 NSPP sample. The entire study sample of 97 California psychiatrists was engaged in clinical practice, which was defined as treating at least one patient a week.

Psychologists who were members of the California Psychological Association (CPA) were randomly selected to participate in the 2000 California Survey of Psychological Practice. The survey was pilot tested with a sample of CPA members and was revised on the basis of suggestions from the participants. Psychologists under the age of 40 years were oversampled to allow for differences between the CPA membership and the age distribution of all California licensed clinical psychologists. The final sample was weight adjusted to account for this oversampling. The survey was a 17-item questionnaire that included items to solicit demographic data on the CPA members. A description of the survey and additional information about its design and sampling procedures are reported elsewhere (

24).

The sample consisted of 770 psychologists; 412 valid surveys were received, for a response rate of 54 percent. This sample of California psychologists was similar in mean age to all licensed psychologists in California. It was also similar in mean age, gender, and race or ethnicity to all California psychologists who at the time of the study were practitioner members of the American Psychological Association (

25). The sample of psychologists used in this study (N=395) comprised only psychologists who were engaged in clinical practice, which was defined as treating at least one patient a week.

Psychiatrists and psychologists who participated in each respective survey provided information on caseload and practice profile characteristics, along with insurance or managed care participation rates. Items in this survey were worded in an equivalent or near-equivalent manner to the items in the NSPP to enable comparison.

Overall comparisons using analysis of variance were first performed on seven profiles of practice. For these comparisons, F tests were used to examine within-group variations versus between-group variations for each profile of practice. For each dimension of practice, between-group variation was significantly different than within-group variation. Individual t test comparisons of each aspect of clinical practice were then made between provider groups. Two-tailed tests were performed to control for type I errors; confidence intervals were set at 99 percent, and unequal variances between the two provider groups were assumed. Hourly wages for each provider group were calculated by dividing net reported income by the total number of weekly hours worked over a 46-workweek period. Median figures for net income, hourly wages, the proportion of total weekly hours spent in solo practice, and the total number of weekly hours worked for each provider group are presented for comparison. Standard errors were adjusted for the weighting and sampling design of each survey by using procedures for complex survey data implemented in STATA 6.0 (

26).

Discussion

This study presents a portrait of the practices of psychiatrists and psychologists since the introduction of managed care and recent changes in treatments. Previous studies have been restricted to samples of consumers or aggregate claims data from individual delivery systems in efforts to chart the distribution of patients by demographic and diagnostic categories and by the financing-arrangement patterns for both provider groups.

In contrast, we used provider data to chart typical weekly clinical practice patterns. This approach measures many of the essential elements of contemporary clinical practice. For the first time, comparative data are presented on the treatments, practice settings, health plan arrangements, income, and discounting practices of these providers. Each provider group is fairly representative of its larger respective national population on many demographic and practice characteristics. It is likely that these results generally represent the clinical practices of both provider groups.

Although statistically significant differences between psychiatrists and psychologists were evident for many dimensions of practice, many of those differences are of little clinical significance. This lack of clinical significance is due to each group's limited provision of services or limited participation in a service—for example, the proportion of time providing group psychotherapy per week—or because there were only minor differences between psychiatrists and psychologists for the services that represented important characteristics of each group's clinical practice, such as hours of direct patient care. Other differences, however, offer evidence of relevant trends in practice within and between the two groups of providers.

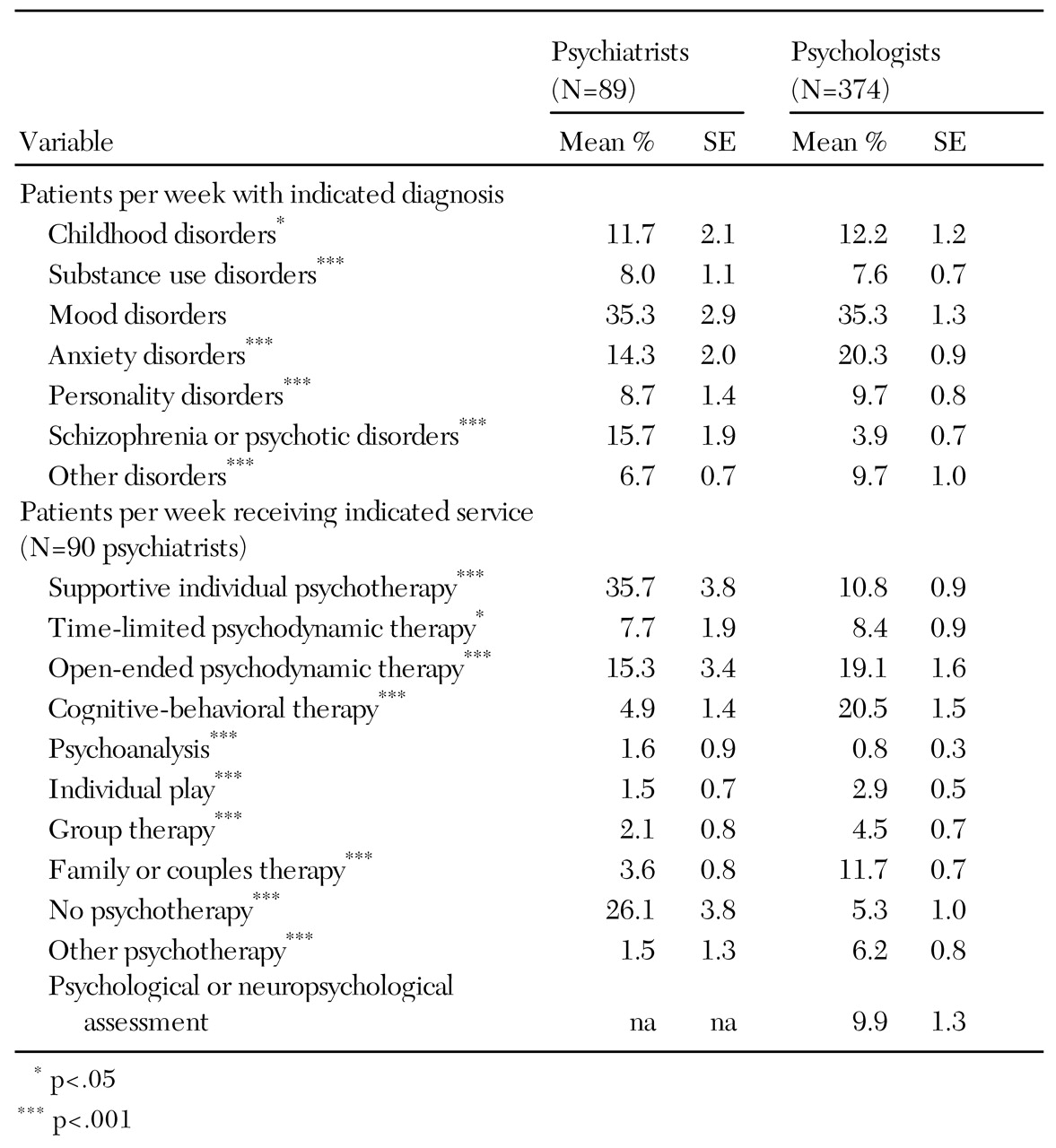

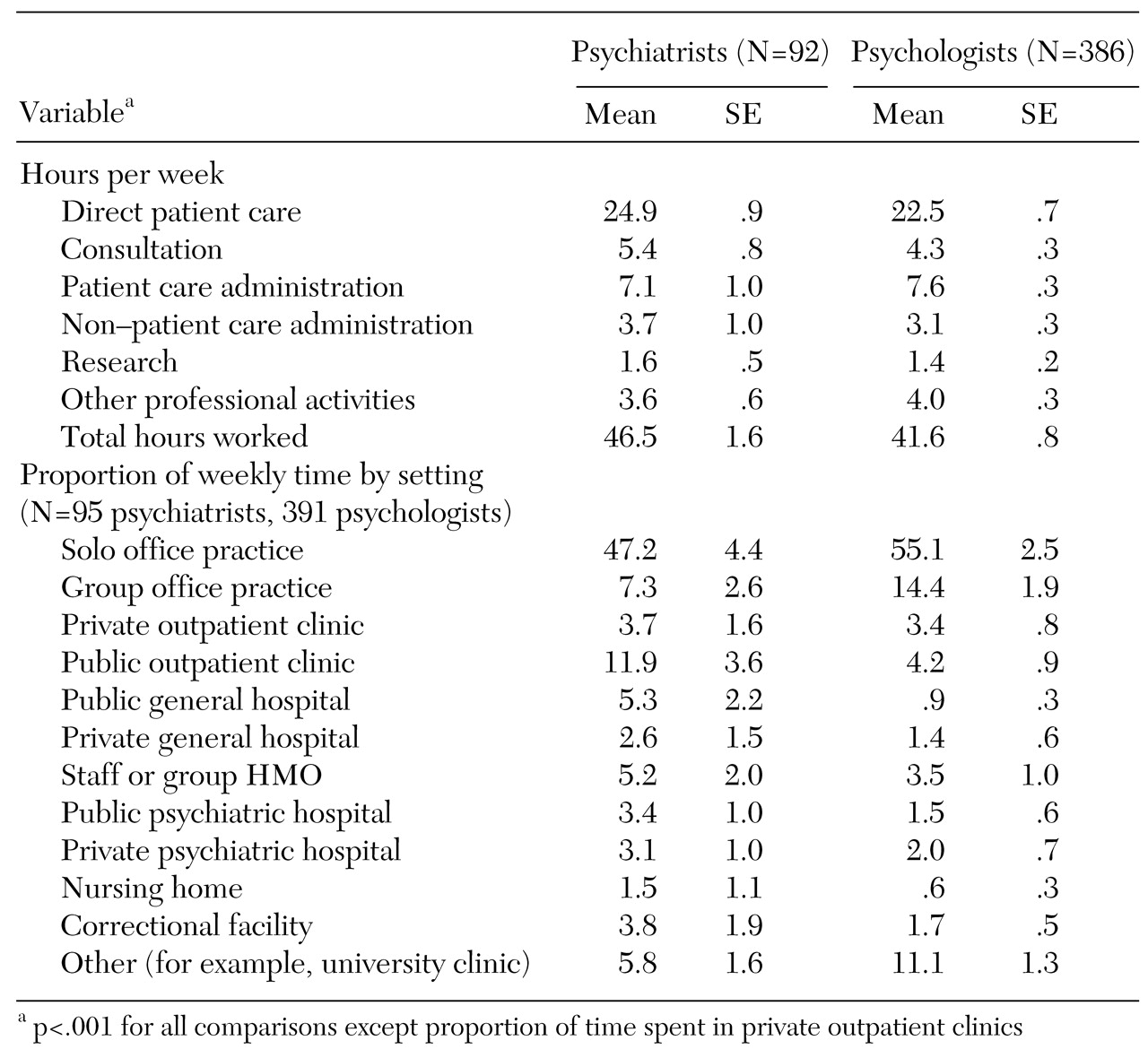

First, psychiatrists treat more patients, participate in more patient visits, and work more hours per week than psychologists. Clinical productivity appears to be greater among psychiatrists than psychologists, perhaps because psychiatrists treat patients who require more intensive treatment or because psychiatrists work in settings that produce larger caseloads, such as hospitals. This difference may be due to other characteristics of psychiatric practice, such as the fact that psychiatrists prescribe medications and schedule medication management visits, which allows them to treat more patients per hour.

Changes in the mental health care delivery system may also influence psychiatrists' workloads. On average, the psychiatrists in this study treated nearly a quarter of their patients with medications alone and treated nearly 60 percent of patients with an overall treatment plan that included medications. This pattern may reflect the impact of managed care policies that promote use of psychopharmacologic treatments alone or combined with treatment from other providers.

Characteristics of psychologists as a group may also affect their clinical activity, such as the higher proportion of women in the psychology field than in psychiatry. Previous studies have shown that female psychologists are more likely to work part-time than male psychologists (

27). In addition, the female psychologists in this study were more likely to have had fewer years of clinical experience than the male psychologists. This characteristic of the sample might account for the differences we observed between psychologists and psychiatrists in important dimensions of practice, such as treatment settings and income sources. Given the growing dominance of women in the profession of psychology, the results of this study may represent practice trends nationwide.

The difference in productivity between the two provider groups may also reflect a longer duration of psychologists' traditional outpatient psychotherapy. The practice patterns of California psychologists in this study may reflect the adverse effects of competition among providers in a market that is saturated with mental health professionals (

22,

25). The emphasis of California psychologists on independent practice, their provision of few clinical services in hospital settings, and the fact that psychologists in California are not licensed to prescribe medications may magnify competition from other nonpsychiatrist mental health care providers.

Second, the results suggest that psychiatrists provide more specialized treatment than psychologists. More than three-quarters of the typical weekly treatments offered by psychiatrists fell into three categories: supportive psychotherapy, open-ended psychodynamic psychotherapy, and medication-only services. Two of these service categories, as presented in the 1998 NSPP, involve medication delivery, which is not provided by psychologists. In contrast, psychologists appear to provide more diverse treatments than psychiatrists. In addition, psychologists vary greatly among themselves in the types of treatment they offer. This variety in practice may exist because of the diverse theoretical and clinical perspectives that dominate contemporary clinical psychology.

However, although this sample of psychologists offers evidence of clinical diversity, the psychologists were largely independent practitioners with minimal reported affiliations with larger systems. Practice in solo and group settings accounted for nearly three-quarters of the psychologists' typical weekly practice locations. Many factors may account for this pattern, including training and personal choice, case mix, absence of hospital admitting privileges, and institutional treatment philosophies and clinical workforce patterns that influence psychologists' ability to diversify their practice settings. Evidence of this limitation in psychologists' clinical affiliations was found in a study of the staffing patterns in one large HMO, which showed reductions over time in the number of psychologists per 100,000 covered lives (

11).

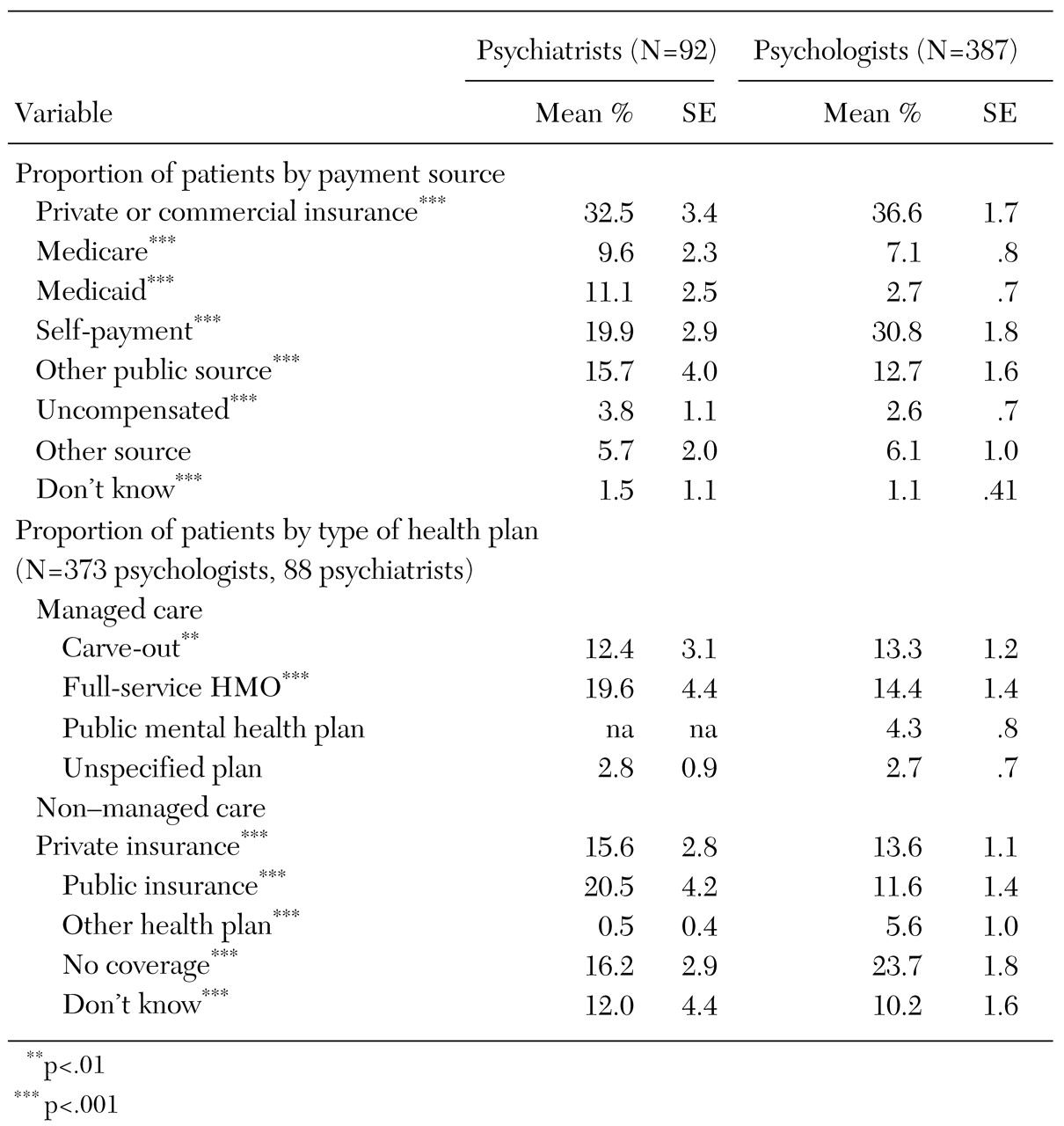

Third, our data on predominant financing sources for both psychiatrists and psychologists update earlier evidence of differences in financing sources between the two provider groups (

3,

6). The psychologists in this study had a higher proportion of patient self-payments among their weekly payment sources than did the psychiatrists. In addition, the psychologists provided nearly a quarter of their services to patients who did not have insurance coverage. This feature of psychological practice may be due to the types of treatments that psychologists provide, such as long-term dynamic or systemic therapies, which are reimbursed for only a portion of the duration of treatment.

Although psychiatrists' treatment settings—for example, public psychiatric hospitals—may be highly related to financing source and the treatment offered, the relationship between treatment, setting, and payment source appears to be less direct for psychologists. Future research may be able to assess whether psychologists' delivery of outpatient services in independent practice dictates the predominant payment sources or whether delivery of specific treatments to particular groups results in psychologists' reliance on particular payment sources and practice locations.

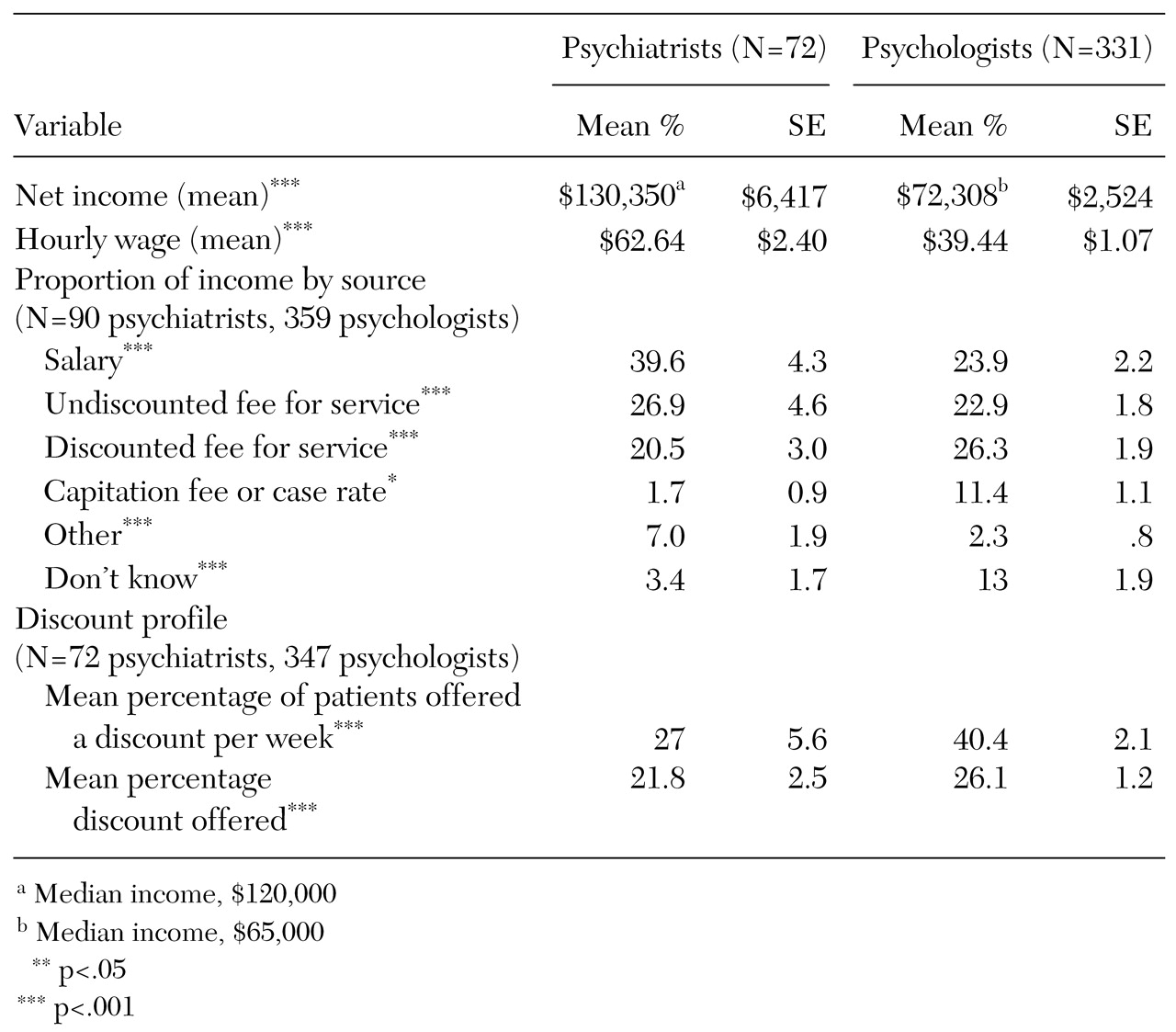

Finally, this study is the first to present comparative income data for both provider groups. Nationally, psychiatrists' income has been reported relative to that of other medical specialty groups, and income for different demographic groups has been reported among full-time psychiatrists from the larger 1998 NSPP sample (

28,

29). Income has been routinely reported among psychologists in full-time practice across disciplines and specialties (

15,

30). In this sample of California psychiatrists, reported net average income was similar to that reported in the entire 1998 NSPP sample of psychiatrists who worked full-time. The net median income of this sample ($120,000) was also equivalent to that of the entire 1998 NSPP (

21).

This sample of clinical psychologists reported a net average income that was nearly $10,000 less than the figure most recently reported in the annual salary survey conducted by the American Psychological Association. However, if the comparison is restricted to full-time clinicians, the two figures are nearly identical. Median income for the sample ($65,000) was also equivalent to that reported in the annual salary survey (

15).

What is striking in this study is the difference in hourly wages and income between psychiatrists and psychologists. The psychiatrists reportedly earned 60 percent more per hour and had an 80 percent higher annual net income than the psychologists. This income difference exists despite the fact that psychiatrists' caseloads include a sizeable percentage of persons with psychotic conditions, who presumably are unemployed, have public insurance that reimburses services at a lower rate than private insurance, or have incomes that may not be sufficient to cover this type of out-of-pocket expense.

The income differential between psychiatrists and psychologists is likely multifaceted and is probably due to such factors as the higher usual and customary fees of psychiatrists and the fact that the psychiatrists in this sample reported more clinical productivity, on average, than the psychologists. The results also suggest that although the two provider groups meet different clinical needs both for California's mental health delivery system and for the patients in that system, this division of labor results in considerable discrepancies in wages and net income.

Although psychologists treat a high proportion of self-pay patients and have a significant presence in mental health carve-out firms (

12), market and organizational dynamics may be exerting significant downward pressures on their incomes. Nationwide, male psychologists and psychologists with more than ten years of clinical experience have more frequently reported decreases in annual salary that they attribute to changes in the health care system (

30). The overall supply of psychologists in a given market may also suppress productivity and income.

One recent study developed several psychologist workforce scenarios using different ratios of psychologists to the treated population. The study estimated that the current supply of psychologists in many states, including California, greatly exceeds the workforce needs of managed care organizations (

22). Evidence of this possible oversupply can be also found in data on the total growth of California licensed psychologists over time. While 11,000 California psychologists held a valid license and practiced their profession in California in 1999, only 5,340 held a license in 1990. This expansion in the psychologist workforce in California represents an 88 percent increase over a ten-year period (

31). Furthermore, a study using these same data estimated that the supply of psychologists per 100,000 persons in the respondents' practice market had a larger negative effect on reported net income in dollar terms than did the psychologists' rate of participation in managed care (

32).

Additional evidence may indicate how competitive pressures adversely affect psychologists' income. The percentage of patients who had discounted fees and the reported average discount per patient were greater for psychologists than for psychiatrists. It is possible that the observed wage and income differences are due to psychiatrists' professional dominance and status (

33), clinical specialization, labor market supply dynamics, and diversification of treatment settings.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the sample of psychiatrists was small, so the practice patterns we observed may not fully represent important characteristics of current psychiatric practice. The observed differences might not be generated—or might even be greater—in a larger sample of psychiatrists. The large proportion of male psychiatrists in our sample and the reported level of weekly time spent in solo practice may have produced different practice patterns than those that would be found in a sample with more female psychiatrists or more psychiatrists who spend less time in solo practice (

34,

35). Second, our data are cross-sectional and may not reflect important longitudinal trends. Third, the study was an exploratory, hypothesis-testing study subject to type I errors as a result of multiple statistical tests. Finally, particular epidemiological and demographic characteristics of the California population and characteristics of the health system in California may have affected these two provider groups in ways that are not evident elsewhere.