Project Liberty was established by the New York State Office of Mental Health in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, to provide free educational and crisis counseling services to residents of the New York City metropolitan area. The program, which is still in operation, provides two broad categories of services: services for persons who have demonstrated symptoms of psychological illnesses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, and outreach to the general population through education and widely available counseling services.

Project Liberty's services were widely advertised through media such as television, radio, and billboards throughout the New York City area starting in November 2001. Details of the Project Liberty program have been published elsewhere (

1). Understanding public awareness and acceptance of this program has important implications for the program itself and potentially for similar programs initiated after urban disasters.

We assessed public awareness of and willingness to make use of Project Liberty's services by conducting a survey of New York City residents several months after the terrorist attacks. We were interested in assessing the level of awareness of Project Liberty, the characteristics of persons who were more likely to have heard of or to say that they would telephone Project Liberty, and whether persons with psychological symptoms were more or less likely to have heard of and to use Project Liberty.

Methods

A random-digit-dial telephone survey (in English and Spanish) of New York City households was conducted during January and February 2002, when the program had been in operation for three months. From the implementation of the program to March 2002, Project Liberty provided more than 42,000 service encounters, including individual counseling and group education sessions, representing services to more than 91,000 persons (

1). The sampling frame for this survey was adults (persons aged at least 18 years) who were living in New York City on September 11. The overall cooperation rate for the survey was 64 percent. The survey included questions about the respondents' demographic characteristics, exposure to the events of September 11, and psychological symptoms since September 11. Further details about the survey and measures used have been published (

2,

3,

4,

5).

We asked respondents whether they had heard of Project Liberty. Persons who had heard of Project Liberty were asked for their impressions of the program and how likely it was that they would make use of Project Liberty's services in future.

We calculated the prevalence of awareness of Project Liberty. We assessed the bivariate relations between the covariates of interest and awareness of and likelihood of telephoning Project Liberty. We also assessed the relations between persons who met criteria for probable PTSD and their awareness of and likelihood of telephoning Project Liberty.

Results

The sample comprised 2,001 adults. The demographic breakdown of our sample was comparable to that of the 2000 U.S. Census for the same sampling area (

6). Overall, 24 percent of persons interviewed (N=480) were aware of Project Liberty. Among respondents who had heard of Project Liberty, 273 (67 percent) had a good impression of the program, and 92 (23 percent) thought that they would telephone the hotline to request services.

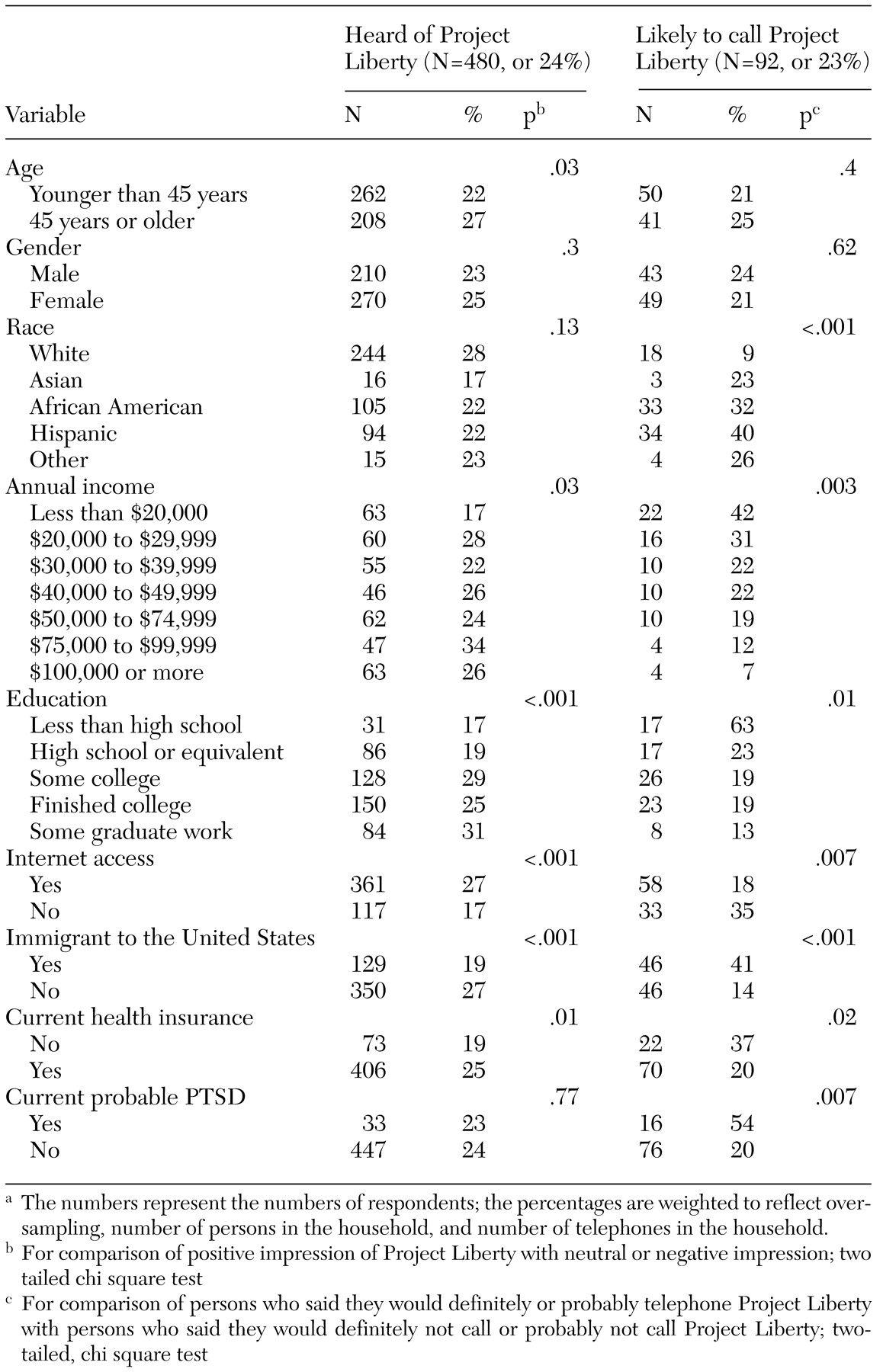

Variables that were significantly associated with having heard of Project Liberty were being older, having a higher income, having more education, having Internet access, being a U.S. citizen, and having current health insurance, as can be seen from

Table 1. Variables that were significantly associated with respondents' reporting that they would be likely to telephone Project Liberty were belonging to a racial minority, having a low income, having less education, not having Internet access, being an immigrant to the United States, having no current health insurance, and having symptoms consistent with current probable PTSD.

Discussion and conclusions

Recent research has shown that the mental health consequences of a large human-made disaster in a densely populated urban area can be substantial (

2,

7). Although a number of approaches have been adopted in the past to provide mental health services to persons affected by various disasters, few formal evaluations of these programs have been published.

Our study showed that despite considerable attempts to inform the public of Project Liberty, only 24 percent of New York City residents had heard of the program four months after September 11. This finding suggests that it is difficult to publicize a program intended to provide counseling services, even when public awareness of issues related to a particular disaster are very high. Encouragingly, among persons who were aware of Project Liberty, perception of the program was largely positive, and persons who reported that they would be likely to telephone Project Liberty had a higher prevalence of mental health symptoms. Persons with indicators of higher socioeconomic status were more likely to have heard of Project Liberty. This finding may reflect greater access within this group to the mass media and other resources. The association between awareness of Project Liberty and Internet access supports this hypothesis. However, we found that persons of lower socioeconomic status said that they were more likely to make use of Project Liberty services.

In conjunction with our earlier observation that persons of lower socioeconomic status may be more likely to experience psychological consequences after a disaster (

4), this finding has two implications. First, Project Liberty may be meeting a need that would otherwise have remained unmet in making mental health services available to persons with lower incomes. Second, greater effort to increase awareness of Project Liberty among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups may be warranted. For example, the lower awareness of Project Liberty among immigrant groups combined with the higher willingness of these groups to use the program suggests that immigrant groups might benefit from targeted marketing of Project Liberty or similar programs after disasters. We also found that persons with symptoms consistent with probable PTSD were more likely to say that they would telephone Project Liberty, which suggests that the program may reach persons who are likely to benefit from its services.

Our study had a number of limitations. Since the time of this study, public awareness of Project Liberty may have grown and public perceptions of the program may have evolved. Follow-up work will be necessary to investigate evolving awareness and perceptions of Project Liberty. We asked respondents only about whether they were likely to use Project Liberty's services; we have no data on respondents' subsequent use of these services. Also, although we explicitly outlined the services provided by Project Liberty, it is possible that some respondents were aware of or planned to use services that were part of Project Liberty without recognizing that these services were in fact Project Liberty services.

In conclusion, our study showed that awareness of available mental health services was low despite considerable attempts to raise awareness of these services. However, we also found that persons who were more likely to say that they would telephone Project Liberty were those who may have had the greatest need for mental health services after the September 11 disaster. Although a formal evaluation of the efficacy of Project Liberty's services is yet to be conducted, early reports suggest that Project Liberty's services are being used by a broad range of residents of the New York City metropolitan area (

8). The results of this study suggest that Project Liberty, although well received by New York City residents, needs to increase its efforts at marketing, particularly to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.