Univariate relationships between predictive variables and serologic results by site were examined for any clear patterns and to reduce the size of the set of predictor variables. Next, to examine the consistency of these relationships across sites, we conducted meta-analyses of the t test and chi square results, again using serologic test results as the outcome variables. We then conducted factor analyses to identify clusters of variables and used these results in regression analyses, the results of which are presented below.

Univariate relationships

Univariate relationships among 38 demographic, psychiatric, psychosocial, and behavioral predictors and four infection-status outcome variables (presence of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or any one of the three infections) were examined separately for each of the five sites by using chi square and t tests. Some relationships emerged as significant in each of the five sites (for example, total overall risk behavior was significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections" in Connecticut (t=−2.28, df=147, p=.024), Maryland (t=−3.36, df=130, p=.001), the public site in North Carolina (t=−2.92, df=175, p=.004), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) site in North Carolina (t=−6.16, df=182, p<.001), and New Hampshire (t=−3.62, df=281, p<.001). However, other relationships were significant at some sites but not others. For example, having a current substance use diagnosis was significantly related to HIV infection among study participants in Connecticut (χ2= 4.71, df=1, p=.030), Maryland (χ2= 8.13, df=1, p=.004), and the public site in North Carolina (χ2=4.61, df=1, p=.032) but not the VA site in North Carolina or in New Hampshire.

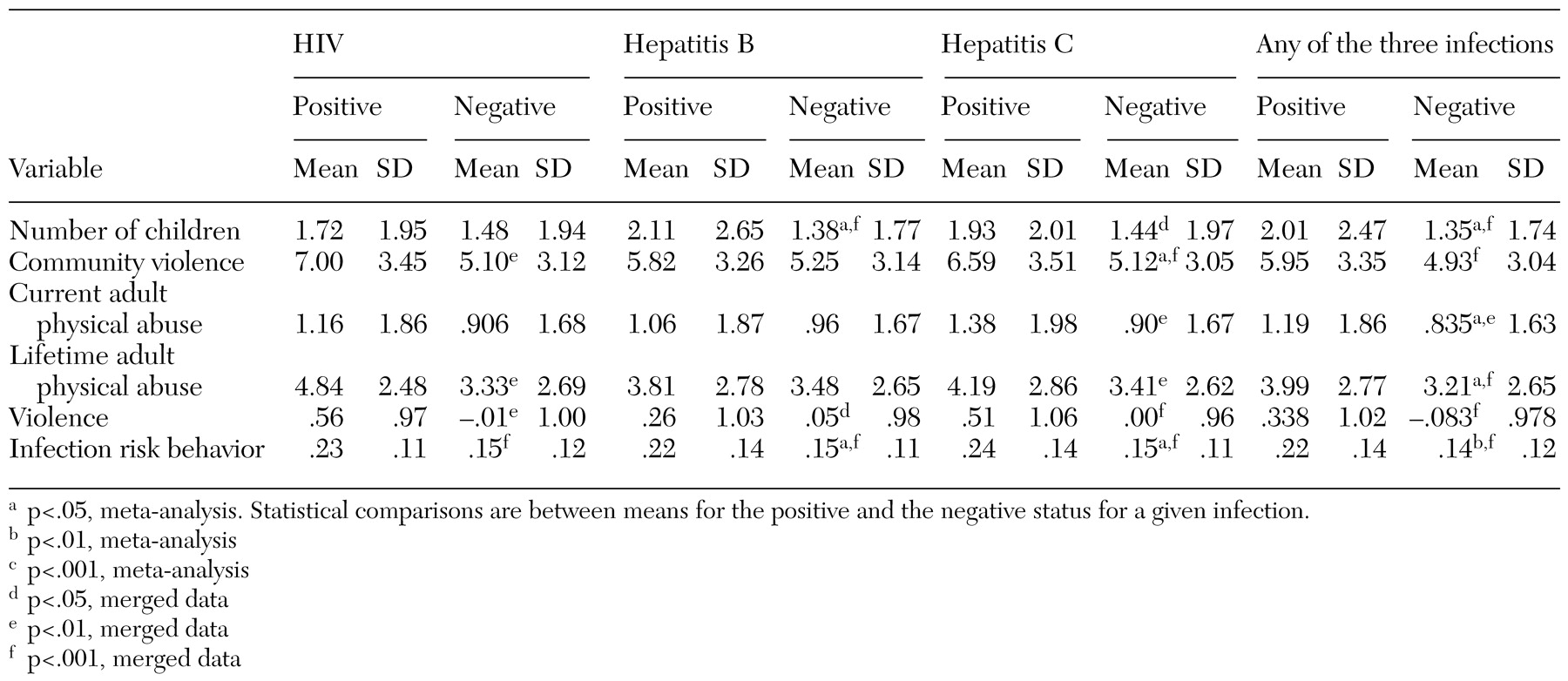

Because no clear pattern emerged across or between sites for most variables, we conducted meta-analyses of the t test and chi square results to look for stable relationships across sites. The results of these meta-analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2, along with the results when all sites were merged and analyzed as a single sample, for comparison purposes. The categorical variables by infection status are shown in

Table 1, and the continuous variables are shown in

Table 2. (Possible scores on the community violence scale range from 0 to 14; on the current and lifetime adult physical abuse scales range from 0 to 9; on the violence scale (Violence Factor Score) range from 0 to 1; and on the infection risk behavior scale range from 0 to 1.)

As can be seen in

Table 1, of the demographic variables, race, gender, and number of children showed some relationship to infection outcomes. Hispanic persons were most likely to test positive for at least one infection. However, race was not significantly related to any single infection. Persons who tested positive for hepatitis B and for at least one of the infections had significantly more children than those who tested negative (p=.025). The relationship between number of children and infection status approached significance (p=.070) for hepatitis C and was not significant for HIV. Finally, in terms of demographic variables, the relationship between HIV and gender approached significance (p=.053), with men more likely than women to be positive for HIV.

Across sites, participants who were HIV-positive were significantly more likely to have been homeless in the previous six months. However, homelessness was not significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections." Study participants who tested positive for at least one of the three infections were significantly less likely to have private health insurance (p=.008). This relationship was similarly significant for each of the infections separately (HIV, p= .008; hepatitis B, p=.036; hepatitis C, p=.045). Furthermore, persons who tested positive for hepatitis B (p=.035) but not for HIV or hepatitis C were more likely to have Medicaid insurance.

Persons who tested positive for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or at least one infection were more likely to have a substance use disorder (p=.039, p=.048, and p=.028, respectively). Persons with HIV, hepatitis C, or any of the infections were more likely to have an alcohol use disorder (p=.003, p=.020, and p=.041, respectively). This finding was observed across sites, except for Connecticut, where persons who tested negative for HIV were more likely to have an alcohol use disorder. Having a diagnosis of PTSD was significantly related to only one of the infection outcome measures—HIV (p=.043). Persons who were HIV-positive were more likely to have PTSD than those who were not.

Study participants who tested positive for at least one of the three infections reported more severe trauma exposure as adults, both currently (p=.048) and across their adult lifetime (p=.027). Trauma exposure was not a significant predictor of each of the three infections separately, although, for lifetime severity of trauma exposure, the relationship approached significance among persons with hepatitis C (p=.058) and HIV (p=.090). For lifetime community violence, persons who tested positive for hepatitis C reported more violence than those who tested negative (p=.048). Similarly, those who were positive for at least one of the infections, or for HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C, separately, were significantly more likely to have been arrested at least once (p=.004, p=.023, p=.035, and p=.001, respectively).

Finally, as would be expected, engaging in risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases was significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections" (p=.005), hepatitis B (p=.012), and hepatitis C (p=.020)—persons who were positive for infection reported more risk behaviors. In terms of the relationship between infection risk behaviors and HIV status, site-specific differences were observed. In Maryland and in the public mental health system in North Carolina, this relationship was significant (p<.001), whereas it was not significant in Connecticut, the VA system in North Carolina, or New Hampshire.

In an attempt to reduce the number of variables used in subsequent analyses, a factor analysis was performed on lifetime community violence, current adult physical abuse, lifetime adult physical abuse, and history of arrest. One factor emerged (eignenvalue=2.209), and all four of the variables loaded onto this factor. These factor scores were then used to create a new "violence" variable, which succinctly summarized the original four variables.

Multivariate predictors across sites

On the basis of the results of these meta-analyses, only variables that were significantly related to at least one of the three infections were used in subsequent multivariate analyses that pooled data across sites. Multiple logistic regressions were used to examine how infection status was related to gender, race, number of children, private health insurance, Medicaid insurance, homelessness, alcohol abuse diagnosis, substance abuse diagnosis, PTSD diagnosis, violence, and behavioral risk for sexually transmitted diseases.

Site was also used as a predictor to capture site-specific differences. The significant predictors of having at least one of the three infections were site, gender, number of children, private health insurance, substance use disorder, and risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases. As can be seen in

Table 3, these variables were also significant predictors of hepatitis B and hepatitis C, except that gender was not a significant predictor of hepatitis B infection. PTSD emerged as a significant predictor of hepatitis B and the only significant predictor of HIV.

To examine the importance of predictors, we ran multiple versions of sequential regressions predicting serologic test results. The variables were entered in five steps: first, site; second, gender and race; third, number of children, risk total, PTSD, and violence; fourth, private health insurance, Medicaid, and employment; and fifth, alcohol abuse diagnosis, drug abuse diagnosis, and homelessness. The strategy for selecting the order of entry was to rank clusters of variables—with the exception of site—from the least modifiable by means of treatment interventions to the most modifiable. These regressions were then run again with site entered last rather than first. Regardless of when site was entered into the model, it was one of the strongest predictors.

Generally, few differences were found between the standard and sequential regressions, and these differences highlighted the same variables found to be important in the meta-analysis. The one difference between the two analyses was that the marginally significant relationship between race and the variable "any of the three infections" found in the meta-analysis was not significant in the regression analysis. This result suggests that the race variable was confounded with one or more of the stronger predictors, such as site. When race was examined in the regression analyses, it accounted for no significant unique effect.

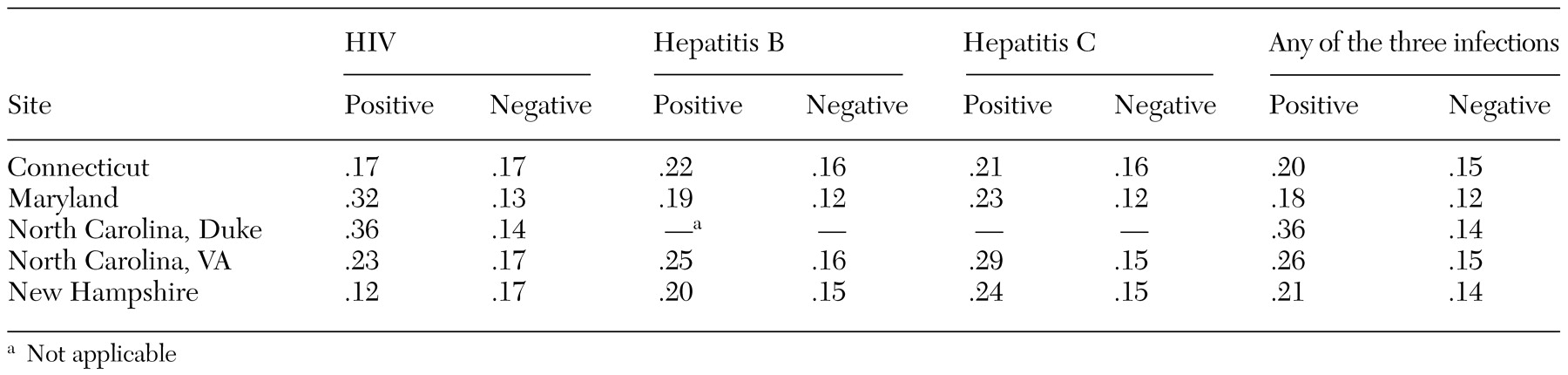

In contrast with identifying variables that could be used to predict behaviors that put an individual at greater risk of hepatitis C infection as opposed to the other infections, these analyses indicated that the sole robust predictor was the total risk variable. Greater total risk predicted a greater chance of infection with any one of the three infections, with hepatitis C alone, and with hepatitis B alone. For HIV, no significant predictors were identified, perhaps because of the low number of positive cases entered into the analyses. The relationship between the most robust predictor of infection—infection-risk behaviors—is shown by site in

Table 4. (Data for hepatitis B and C from the public mental health system in North Carolina are absent from the table because information on hepatitis was not collected at that site.)