A total of 21 reports were reviewed. The reports are discussed here from three perspectives: patterns of aftercare service use, the effectiveness of these services, and predictors of use.

Patterns of use

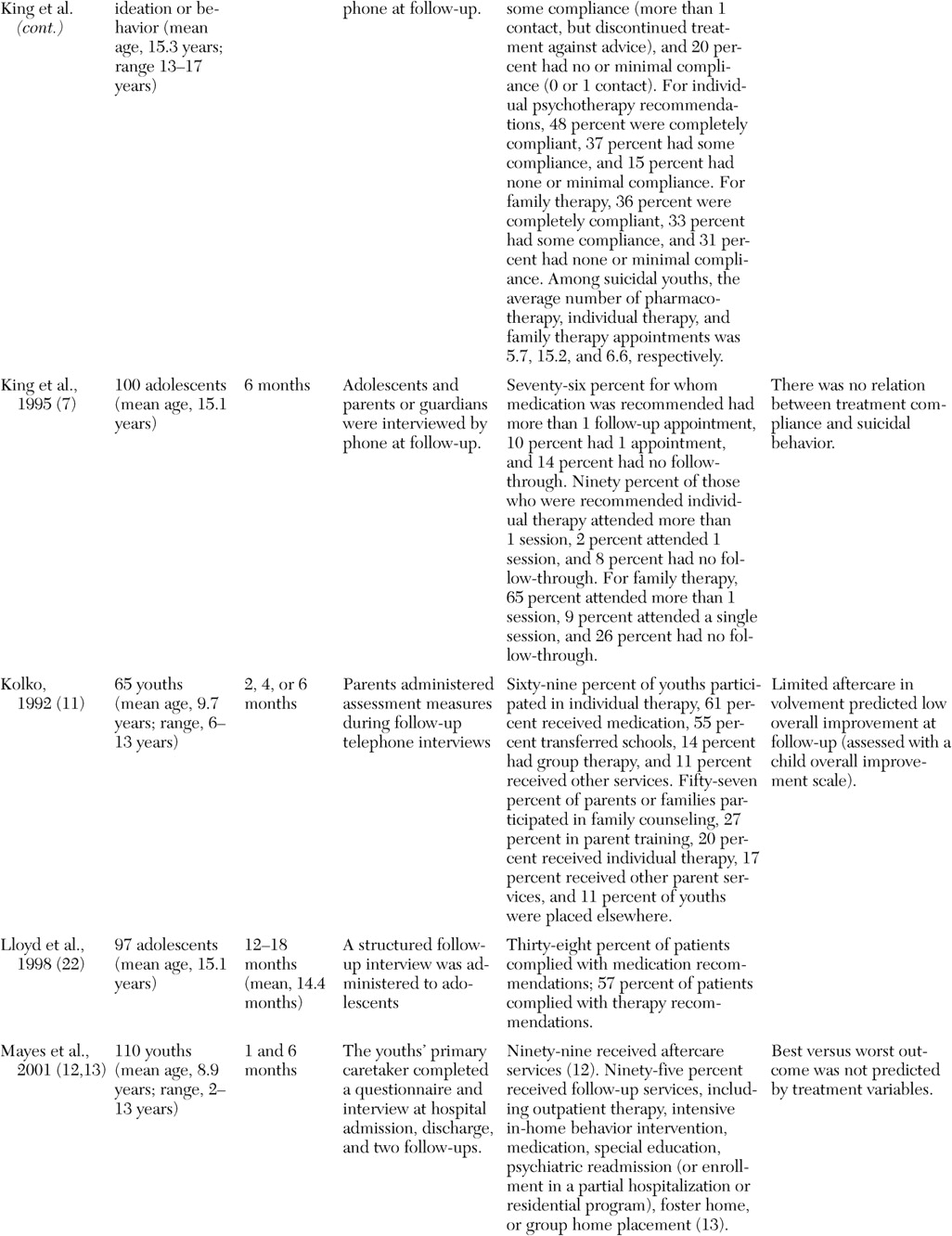

The studies that identified rates of initiation of aftercare services or rates of compliance with aftercare services among youths are summarized in

Table 1. As the table shows, most studies that examined rates of initiation of aftercare services found that approximately two-thirds or more of the youths received at least some services after being discharged from the hospital (

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17). Notable exceptions included the rate of aftercare service use that was reported at the comparison sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (

18) and the rates of follow-through with appointments for medication management at community mental health centers that were reported in another study (

19). The decreased rate at the comparison sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (

18) may be attributable in part to the fact that data on aftercare services were collected by using financial records; however, data on aftercare service use that were obtained outside of the CHAMPUS system would not have been recorded. In the other study, the decreased rate may be partially related to the fact that rates of aftercare service use were estimated from clinical records at the community mental health centers (

19). This procedure also may have resulted in conservative estimates of aftercare service use, particularly if youths and families obtained services outside the mental health centers or if they obtained services that were not originally recommended.

Although a majority of youths in the studies that we reviewed eventually received at least some aftercare services, they did not always receive their first services promptly or when it was first intended. For example, Goldston and colleagues (

4) found that most outpatient mental health service use (73 percent of 80 youths) was initiated within the first month after discharge. However, adolescents and families continued to seek new services even after that point. More specifically, 92 percent of the youths ultimately received some form of outpatient care up to eight years after their hospitalization. In a similar manner, Parmelee and colleagues (

14) found that only 61 percent of 79 youths and families kept their first scheduled aftercare appointment, but a greater proportion of youths (83 percent) eventually received services.

Several investigators described specific types of aftercare services that were received by youths (

4,

5,

11,

14,

17). Across studies, individual therapy seemed to consistently be among the most commonly used—if not the most commonly used—and recommended type of aftercare service (

4,

7,

9,

11,

17). Pharmacotherapy and family therapy also appeared to be highly used and recommended, although rates of the use of these services appeared to differ somewhat across sites and studies (

4,

5,

7,

8,

9,

11,

14,

17). Group therapy, including self-help groups, appeared to be used less frequently among child and adolescent psychiatric patients, although participation in groups appeared to be commonly recommended for youths with alcohol and substance use problems (

10,

20,

21). Few studies documented mental health services that were received through the schools or juvenile justice system; although it is clear that youths who were discharged from psychiatric hospital settings often received school services and have contact with the legal system (

14,

15,

17). At least one study suggested that a majority of youths received multiple forms of aftercare services (

4). However, only one of the naturalistic follow-up studies examined the extent of case management among formerly discharged patients (

17), despite its potential utility in improving coordination and continuity of care after discharge (

18).

Even when youths and families received aftercare services, they often did not participate in these services for as long as recommended (

7,

8,

9,

22). Across studies that examined compliance with the three types of therapy, pharmacotherapy and individual therapy appeared to be associated with higher rates of compliance than family therapy (

7,

8,

9). However, rates of compliance with recommended pharmacotherapy appeared to vary across studies and sites (

6,

7,

8,

9,

19,

22).

Few studies examined the actual number of appointments of aftercare services that were kept by youths and families, regardless of the recommended number of appointments. Particularly for individual therapy, data for the number of appointments that were kept have varied widely. For example, Solomon and Evans (

17) reported that 20 youths who were discharged from a state psychiatric hospital attended an average of 4.3 individual therapy appointments in two months. In contrast, King and colleagues (

9) reported that among 61 suicidal youths, the average number of individual therapy sessions was 15.2 in six months. The extent to which these differences reflected the differing lengths of follow-up or reflected sample characteristics is unclear. The number of pharmacotherapy visits was more consistent across studies (

6,

9,

17). For example, in the two studies with the largest samples that reported the number of aftercare service visits, the number of pharmacotherapy visits ranged from 5.4 (N=77) (

6) to 5.7 (N=51) (

9).

In terms of length or duration of treatment, Spirito and colleagues (

23) found that among 84 youths who received psychotherapy after discharge from either a general or a psychiatric hospital, 57 percent were classified as having had at least monthly or bimonthly sessions three months after discharge. For a mixed psychiatric inpatient sample, Goldston and colleagues (

4) estimated that between 71 percent and 81 percent of adolescents who received individual therapy (N=148), family therapy (N=89), group therapy (N=59), or pharmacotherapy (N=116) continued in treatment three months after service initiation. Similarly, in two samples from inpatient substance abuse treatment facilities, attendance in 12-step groups three months after discharge was reported by 60 percent (N=91) (

20) to 75 percent (N=99) (

10) of youths.

In sum, it appears that most youths who were discharged from inpatient settings received at least some aftercare services. Individual therapy, pharmacotherapy, and family therapy appear to be the most commonly used aftercare services. Regardless of initial use of services, estimates of the length of aftercare services varied quite widely among studies. Missed appointments and lack of full compliance with aftercare recommendations appeared to be common. Nonetheless, findings from several studies converge in suggesting that a majority of youths receiving aftercare service continued to do so three months after hospital discharge.

Effects of use

To examine the effectiveness of aftercare services, a minimum requirement is that a comparison be made between a sample that received aftercare services and a sample that did not receive those same services. Or a comparison could be made between samples that received different amounts or different types of aftercare services. Without such comparisons it is impossible to determine whether the effects are a result of participation in the treatment program per se or are simply a result of the passage of time, the increasing maturity of the youths who are being followed, an artifact of the manner in which outcomes are assessed, or a particular characteristic of the target population that is being followed.

Randomized controlled trials in which youths (or sites) are assigned to receive aftercare services or no aftercare services, different types of aftercare services, different forms or frequencies of aftercare services, or specialized aftercare services compared with treatment as usual would be the ideal approach to examining the effectiveness of aftercare services. However, restricting recommended treatment choices—as in the case of assigning a youth to aftercare services or to no aftercare treatment—is not ethically justifiable. Thus we were not able to locate any randomized controlled trials of aftercare services among children or adolescents who were previously hospitalized.

Given the dearth of controlled studies, investigators have had to infer information about the effectiveness of aftercare services from studies of youths who either complied or did not comply with aftercare recommendations, from studies of youths who received either more or fewer aftercare services, or from naturalistic prospective studies in which some youths received specific aftercare services and others did not. The results of such studies may provide indirect indications of the effectiveness of aftercare services, but they are tempered by the fact that youths and families who self-select or remain in aftercare services or who are compliant with aftercare treatment recommendations may differ in important ways from youths and families who do not participate in aftercare services.

With that caveat, we found six studies that examined whether aftercare service use was associated with reduction in severity of symptoms. These studies are summarized in

Table 1. Three of these studies focused on outcomes among youths who were hospitalized in general psychiatric settings, whereas the other three focused on outcomes among youths who received inpatient substance abuse treatment. For the first three studies, no clear conclusions can be reached about whether a relationship exists between aftercare service use and outcomes. One of these studies found that aftercare service use or involvement was not related to suicide attempts (

7). In another study, rates of combined treatment were also not found to be associated with the likelihood of suicide attempts, but antidepressant use during follow-up was related to increased suicide attempts (

16). In an additional study, limited involvement in aftercare services predicted low overall improvement at follow-up (

11). By contrast, all three studies of youths who were discharged from substance abuse facilities found that greater involvement in aftercare services was related to lower risk of substance use or greater likelihood of abstinence (

10,

20,

21).

Although studies that focus on symptomatic improvement obviously are important, Hoagwood and Koretz (

24) suggested that efforts to assess the impact of mental health interventions should also focus on other domains, such as level of functional impairment, consumer perspectives, environmental contexts, and service systems. Nonetheless, only one study that we found examined the effects of aftercare service use on functional impairment (

12), and we did not find any studies that examined the effect of aftercare service use on consumer perspectives, such as patient or family satisfaction, or on environmental contexts, such as the quality of family and peer relationships. The importance of assessing the impact of interventions on customer satisfaction was illustrated by findings from the Fort Bragg Evaluation study in which the provision of a case manager and continuum of clinical services did not necessarily reduce costs for enrolled families, but it did result in greater satisfaction among those who received the services (

25).

The Fort Bragg Evaluation study was the only study that we found that examined the effects of aftercare services on service systems, such as the rates of rehospitalization or out-of-home placement (

18). The Fort Bragg Evaluation study showed that aftercare services did not appear to be related to the likelihood of rehospitalization. The paucity of studies that we found that examined the effects of aftercare services is alarming, given the particularly high rate of rehospitalization and out-of-home-placement among youths who were hospitalized previously. For example, Arnold and colleagues (

26) examined data for 180 psychiatrically hospitalized youths and found that 44 percent had one or more rehospitalizations. Of these youths, 19 percent had been rehospitalized within six months after discharge, and 23 percent were rehospitalized on multiple—between two and 13—occasions.

Predictors of use and discontinuation

Andersen and Newman (

27) proposed a framework for viewing health service use that suggests an interaction among predisposing factors, enabling factors, and perceived need in the use of services. In this model, predisposing factors—such as demographic characteristics, social structure, and health beliefs and attitudes—increase the likelihood that treatment will be considered a viable option for persons who are faced with illness. Enabling and impeding factors are personal, family, or community resources or variables that affect the likelihood that patients or families will be able to obtain and use services. Perceived need refers to the perception of the patient, family, or experts as to the severity of the illness. In the latest version of this model, these factors influence each other and work as a whole in affecting service use (

28). This model provides a useful framework within which to review current research.

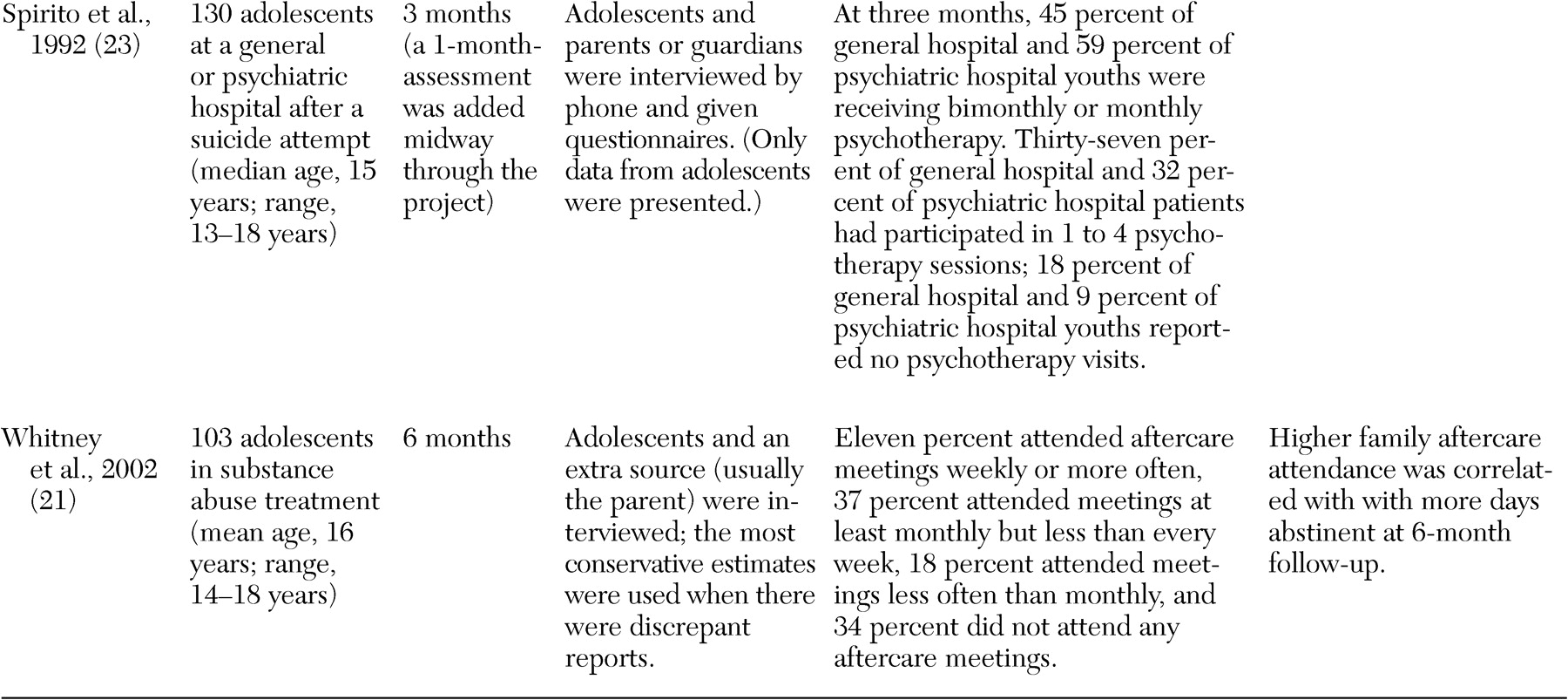

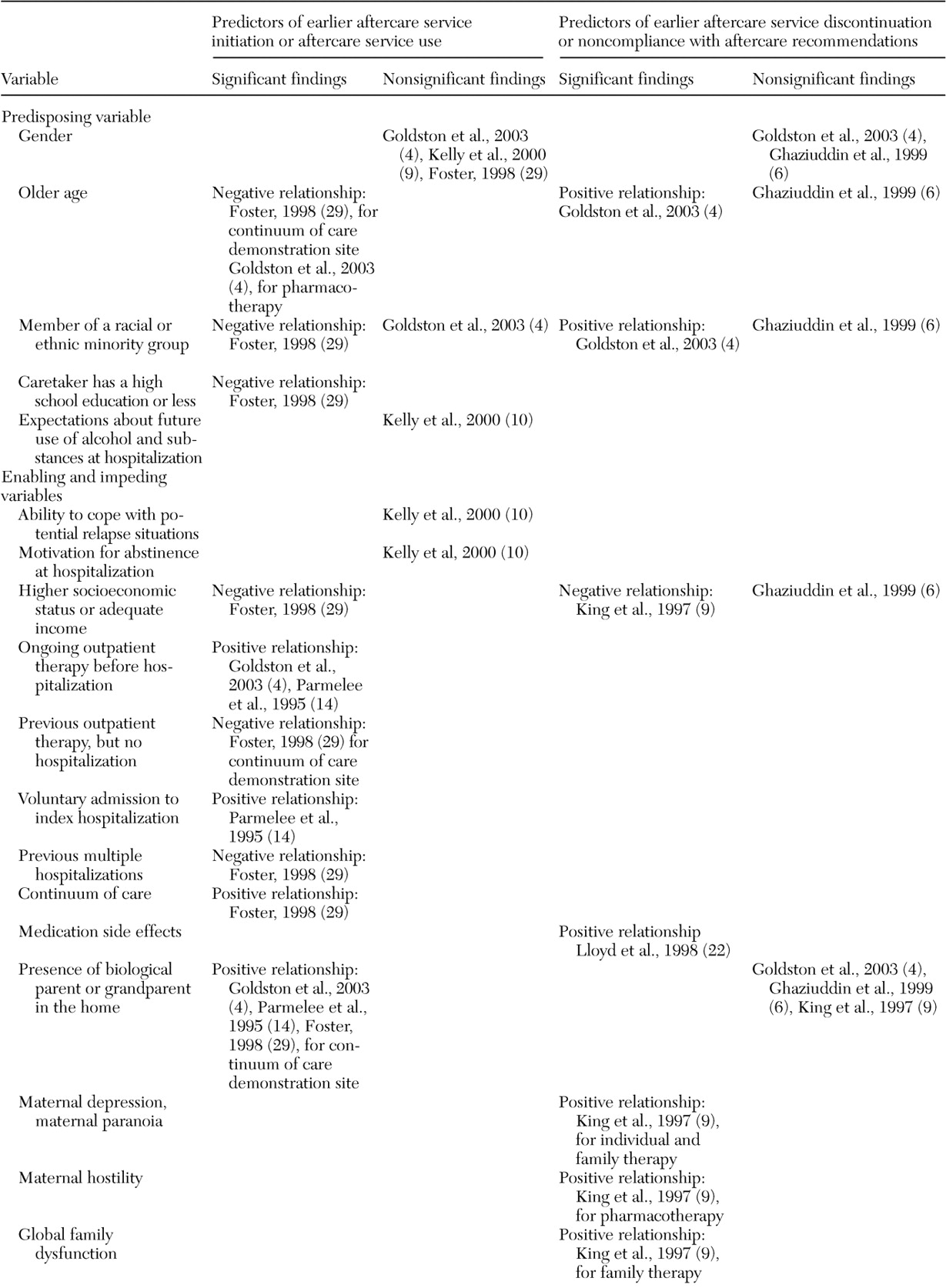

As can be seen in

Table 2, the number of studies about predictors of initial use and discontinuation of aftercare services is quite limited in the sense that few variables have been examined in more than two studies. Nonetheless, several identifiable trends or replicated findings in the literature are noteworthy. For example, across four studies it appeared that gender did not influence whether youths entered into or remained in aftercare services (

4,

6,

10,

29). On the other hand, it appears that younger age may be related to aftercare use. In one study, younger age was related to aftercare use in the first 30 days after discharge, primarily for pharmacotherapy (

4). In another study, younger age was related to earlier use of aftercare services at the continuum of care demonstration sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (

29). Also, findings have been mixed about whether younger age was related to longer use of or compliance with recommended services (

4,

6). Inconsistencies have been found for whether there is a relationship between race or ethnicity and use of aftercare services. However, studies have suggested that youths from minority groups may enter aftercare services at a slower rate (

29) and that they may not remain in aftercare services as long as other youths (

4). Such findings, if replicated, would be consistent with data that suggest that minority youths with psychiatric disorders may receive fewer mental health specialty services in the community than other youths (

30).

Enabling and impeding factors may also be important predictors of aftercare service use. For instance, one study found that history of outpatient therapy, but not hospitalization, was associated with longer time until aftercare follow-up when there was an adequate continuum of care (

29). However, this study did not describe when these past outpatient contacts occurred, and it is possible that recent contacts with mental health services may have a more facilitative effect in aftercare use. For example, in two studies, being in outpatient therapy just before hospitalization appeared to increase the likelihood of entering aftercare services or continuing in outpatient therapy after hospitalization (

4,

14). Presumably, youths and families who were engaged in treatment just before hospitalization already had overcome some of the barriers to gaining access to outpatient services (

31). In addition, the results from the Fort Bragg Evaluation study suggest that having an adequate continuum of care and case manager services increases the likelihood of receiving aftercare services earlier after discharge—a 16-fold increase after other variables were considered (

29). In addition, much like the finding that outpatient therapy before hospitalization increased the likelihood of aftercare service use, having adequate coordination and continuum of care may reduce barriers to entering outpatient treatment after hospitalization. Other service system variables—such as type of insurance coverage, aspects of managed care, wait list for new appointments, scheduling practices of service systems, availability of appointments, restrictiveness of policies for third-party payer sources, and accessibility of service locations—apparently have not been examined in relation to the likelihood of youths' gaining access to care after hospitalization.

Goldston and colleagues (

4) found that the presence of at least one biological parent or grandparent in the home was associated with greater access to aftercare services in the first month after hospitalization. At the continuum of care demonstration site, Foster (

29) found greater aftercare service use when a father was in the home. Logan and King (

32) pointed out that parental figures have important roles in recognizing the need for treatment and gaining access to care for children and adolescents. One study in particular suggested that less compliance with aftercare recommendations may be related to family problems; maternal depression, hostility, and distrust; and a poor relationship between adolescent and father (

9). Such findings suggest that parental problems and difficulties in relationships with parents interfered with follow-through with aftercare recommendations or the recognition of need for aftercare services. Poor parent-child relationships and parental psychological problems may, of course, be interrelated with the problems that are experienced by the child or adolescent. Youths' mental health and behavioral problems may have an impact on others, just as youths' problems may be triggered, exacerbated, or maintained by what is going on in the family.

In Anderson and Newman's model (

27), perceived need and illness severity are potential correlates of health service use. There was no strong or consistent evidence that suggested that the presence of a psychiatric disorder, psychiatric comorbidity, or symptoms per se is related to aftercare service use (

6,

4,

29). Similarly, history of a single suicide attempt, recent suicidality, and even severity of suicidality did not appear to be related to aftercare service use (

4,

15,

29), although repeat suicide attempts were related in one study to longer time in aftercare services and greater use of family therapy (

4). In an inpatient sample—which by definition is characterized by a high degree of psychiatric problems—psychiatric disorders or symptoms may not differentiate youths in terms of their subsequent service use as much as other factors.

Another possible indicator of need is caregiver burden. However, only one study examined the relationship between the burden posed by a child's psychiatric problems and its relationship to aftercare service use (

29). Paradoxically, that study found that objective burden—which was reflected in difficulties or changes in routine or lifestyle caused by the child's problems—was related to use of aftercare services sooner after discharge. However, that study also found that more subjective indexes of burden—for example, guilt or worry—were related to less timely service use. Further studies are needed to examine the relationship between the burden that is caused by a child's psychiatric problems and how the burden affects the likelihood of gaining access to needed services.