Visits to hospital emergency departments for nonurgent needs have been estimated to account for up to 85 percent of all admissions to medical emergency departments. Such visits create an undue financial burden and limit the availability of urgent care for patients who need it (

1,

2,

3,

4).

Only a few studies have examined this issue for psychiatric emergency departments. One study at a hospital in Dallas showed that one-quarter to one-third of more than 2,000 visits were for nonurgent needs (

5). In one study of 52 patients in Cleveland, 69 percent of the patients endorsed a need for information and advice and 64 percent for financial assistance (

6). These findings suggest that there is a mismatch between the services that patients believe are available and those that most psychiatric emergency departments are equipped to deliver.

Few investigations have examined approaches that patients take to managing their symptoms before they present to the psychiatric emergency department. In one survey of 200 patients, only 35 percent had previous contact with a mental health professional, and only 5 percent acknowledged using illicit drugs or prescription medication in an attempt to regulate their symptoms (

7).

In the study reported here, we investigated the hypothesis that there is a significant amount of inappropriate use of the psychiatric emergency department and sought to understand approaches to obtaining treatment among persons who use the psychiatric emergency department.

Methods

A brief, self-report, paper-and-pencil survey was administered in the psychiatric emergency department at Butler Hospital, a private, nonprofit freestanding psychiatric facility in Providence, Rhode Island. Butler Hospital serves as the primary teaching site of the department of psychiatry of Brown Medical School and receives patients from Rhode Island and neighboring Massachusetts. The hospital's emergency department is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

During the one-month period of July 2003, psychiatric emergency department intake coordinators were instructed to offer all patients the seven-item survey form and to indicate that the form could be completed anonymously. For patients who completed the survey nonanonymously, demographic data, primary DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis, and disposition were obtained from the medical record. The hospital's institutional review board approved the study.

Content-similar responses to open-ended questions were grouped together. Responses to the multiple-choice question "What services are you hoping to receive at the psychiatric emergency room today?" were categorized as either appropriate or mismatched on the basis of concordance with routinely available psychiatric emergency department services. "Appropriate" services included treatment recommendations; admission to an inpatient unit; crisis counseling, support, or advice; diagnostic evaluation; admission to a day hospital; and substance detoxification or rehabilitation. "Mismatched" services included tests, prescriptions for medications, referral to outpatient providers, family therapy, and a physician's letter for documentation of illness.

Results

Eighty-two patients completed surveys, of whom 60 (73 percent) included their name. Because of fluctuations in psychiatric emergency department acuity and inconsistent patient solicitation, the number of patients who were offered the survey is not known. However, approximately 400 patients presented to the emergency department during the month. The composition of the study sample was very similar to the total population of persons presenting to the emergency department for the month in terms of age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, and insurance status.

The subset of 60 patients who completed the survey nonanonymously comprised 28 females and 32 males. These patients' ages ranged from nine to 81 years, with a mean±SD age of 31±14.5 years; parents completed the survey for children. Fifty-four study participants (90 percent) were Caucasian, four (7 percent) were Hispanic, and two (3 percent) were African American. Two-thirds of the patients (N=38) had commercial health plans or Medicare, and the remaining third (N=23) were receiving public assistance or had no coverage. Primary psychiatric diagnoses were affective disorder (34 patients, or 62 percent), substance use disorder (nine patients, or 16 percent), psychotic disorder (six patients, or 11 percent), anxiety disorder (two patients, or 4 percent), and other disorders (four patients, or 7 percent). More than half the sample reported that they had been to this particular psychiatric emergency department before.

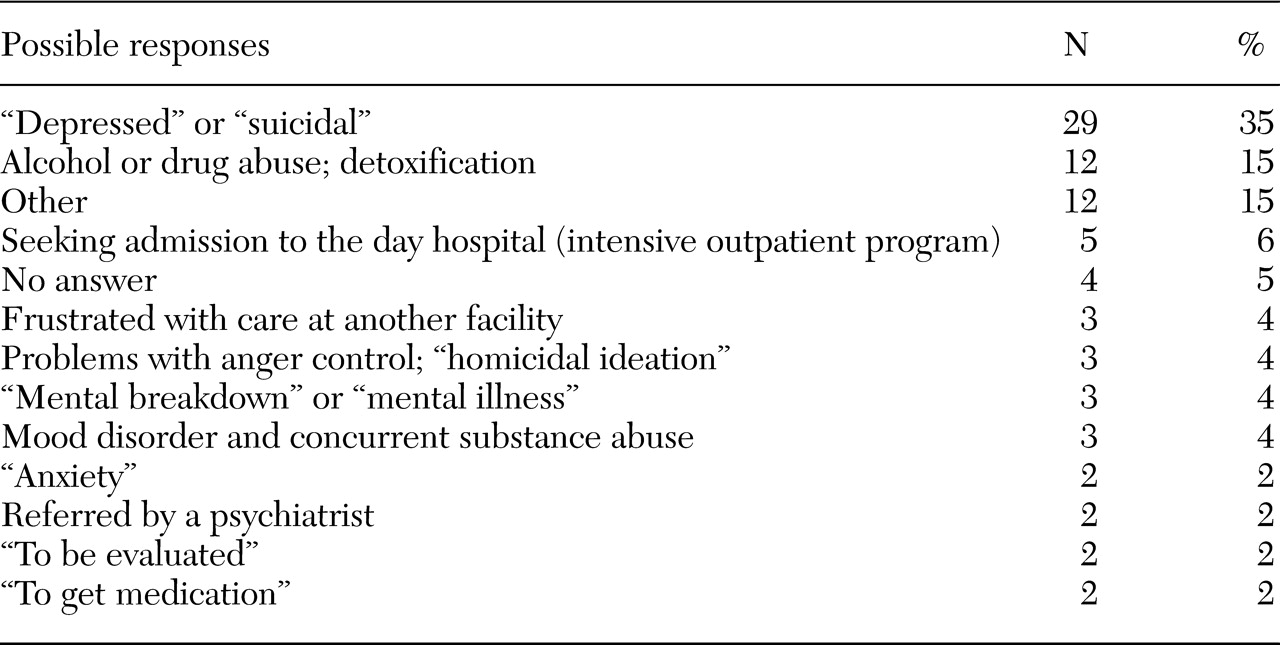

Responses to the open-ended query "What is the main reason you came to the psychiatric emergency room today?" are shown in

Table 1. In addition, patients were asked to endorse one or more of 12 possible services for the question "What services are you hoping to receive in the psychiatric emergency room today?" The great majority of patients had at least one appropriate expectation; only eight patients (10 percent) had exclusively mismatched expectations. However, nearly half the respondents (37 respondents, or 45 percent) endorsed at least one mismatched service expectation. These patients were significantly younger than the 45 patients (55 percent) who had exclusively appropriate expectations (28.1±2.2 compared with 39.0±2.6 years; t=3.1, df=80, p=.003), but knowledge of psychiatric diagnosis, previous experience in this facility, and previous contact with a health care provider did not differentiate these groups.

Three-quarters of the 58 patients with disposition data (N=43) were admitted to the inpatient or day hospital, and one-quarter (N=15) were discharged home. Of the 15 patients who were discharged, six had service expectations that were exclusively appropriate, five had exclusively mismatched expectations, and four had mismatched service needs in addition to at least one appropriate expectation. The patients who were discharged home were significantly more likely to have exclusively mismatched service expectations compared with those who were admitted to the inpatient or day hospital (χ2=6.1, df=1, p<.05).

Of 18 possible responses to the question "What other things did you try before you came to the hospital today?" the patients endorsed a mean of 3.9±3.9 responses. Two-thirds reported "talking to friends or family for advice or support," and more than half endorsed taking prescribed medication and consulting with a physician or therapist. Self-directed efforts to reduce symptoms were common: roughly one-quarter of respondents used nonspecific relaxation techniques, and 45 percent used alcohol or illicit substances for this purpose.

Discussion and conclusions

Several important findings emerge from this pilot study of psychiatric emergency department utilization. Nearly all patients had psychiatric needs that they believed required attention in a relatively short time frame. Only 25 percent of visits were judged to be nonurgent and appropriate for routine outpatient care. This proportion is well below the estimate of 85 percent for nonurgent use of medical emergency departments but consistent with a previous estimate of 25 to 30 percent for psychiatric visits (

5).

The second key finding involves the types of service expectations endorsed by patients who presented to the psychiatric emergency department. Although the great majority of patients endorsed at least one service need that was available at the psychiatric emergency department, 45 percent of the whole sample and 60 percent of those who were discharged to outpatient care reported hoping to receive services that were not routinely offered. The patients who had mismatched expectations were younger than those who had exclusively appropriate expectations, possibly reflecting less experience with psychiatric services. However, it is notable that even those who had a previous visit to the psychiatric emergency department had mismatched expectations.

A final noteworthy observation was the diversity of strategies patients used before they came to the psychiatric emergency department. More than half reported that they first contacted friends or family. This finding contrasts with the 14 percent reported elsewhere (

7) and indicates that our sample may have been less socially isolated than other cohorts. In addition, 45 percent of our sample used illicit drugs or alcohol to ameliorate their symptoms. This finding suggests that it may be important to outfit and train personnel to handle substance-related complications in such facilities.

The use of a unique survey form and a small sample may have limited the generalizability of our findings. However, despite these limitations, this study provides useful insights into the characteristics and expectations of patients who use the psychiatric emergency department. We conclude that use of the psychiatric emergency department was consistent with its mission. However, the fact that 45 percent of respondents endorsed a need for an unavailable service underscores the importance of providing better education to the public about how to obtain mental health services and improving access to such services.