Limited progress has been made in developing effective interventions to manage insight deficits and nonadherence among psychotic patients. In one controlled trial, a brief cognitive-behavioral intervention was associated with significantly improved insight into illness and reduced symptom severity compared with usual care for patients with schizophrenia (

17). A type of cognitive-behavioral therapy that focused specifically on improving antipsychotic adherence also proved to be effective (

18) and durable (

19) in a mixed sample of psychotic patients. However, a replication of the study in a sample that was limited to patients with schizophrenia did not show a significant improvement in adherence (

20). Psychoeducational interventions for schizophrenia have tended to demonstrate little effect on insight (

21) or adherence (

22).

Little is known about the routine psychiatric management of nonadherence to antipsychotic medications among patients with schizophrenia who lack awareness of their illness. Information is sparse regarding how psychiatrists manage these patients and whether and to what extent commonly provided clinical interventions improve adherence among patients who lack insight into their illness. By examining the effects of patients' insight into their illness on the clinical presentation and management of nonadherence as well as the treatment response among patients with schizophrenia, we hope to inform efforts to improve the clinical management of nonadherence to antipsychotics among patients who are not aware that they have a mental illness.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of psychiatrists was surveyed by mail to assess their management of patients with schizophrenia who had been nonadherent to antipsychotic medication regimens. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of New York State Psychiatric Institute and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education. Primary data collection was conducted from September 2003 to January 2004.

A random sample of psychiatrists was selected from the American Medical Association's Masterfile of Physicians. Psychiatrists who were in psychiatric residency training, living outside the United States, over the age of 75 years, and not involved in direct patient care were excluded. Selected psychiatrists (N=1,150) were sent a prescreening postcard to determine whether they had treated at least four patients with schizophrenia in the past typical work month. Analysis of the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (

23,

24) indicated that more than 90 percent of patients with schizophrenia who were receiving psychiatric care were being treated by psychiatrists who treated four or more patients with schizophrenia per month.

When the psychiatrists who reported treating fewer than four patients with schizophrenia per month were excluded, the sample was reduced from 1,150 to 880. An additional ten psychiatrists were excluded from the sample because the screening postcards were returned with "addressee unknown" indicated and a follow-up telephone inquiry revealed no forwarding contact information. These exclusions resulted in a final sample of 771 psychiatrists who met eligibility criteria and had a serviceable mailing address.

In this sample, 534 psychiatrists responded to the survey, for a response rate of 69 percent. Of these 534 psychiatrists, 310 reported on an eligible patient who met the study criteria of being older than 18 years; being under the psychiatrist's care for at least one year; being nonadherent to oral antipsychotics at some point in the past year, defined as taking less than half of the prescribed medication for at least two consecutive weeks; not receiving an injection of depot antipsychotic medication during the two months before nonadherence to oral antipsychotics; and being the last patient the psychiatrist saw who had these characteristics. The other participating psychiatrists (N=224) provided general information about their management of medication nonadherence among patients with schizophrenia, but not individual patient-level information. This information was not analyzed for this study.

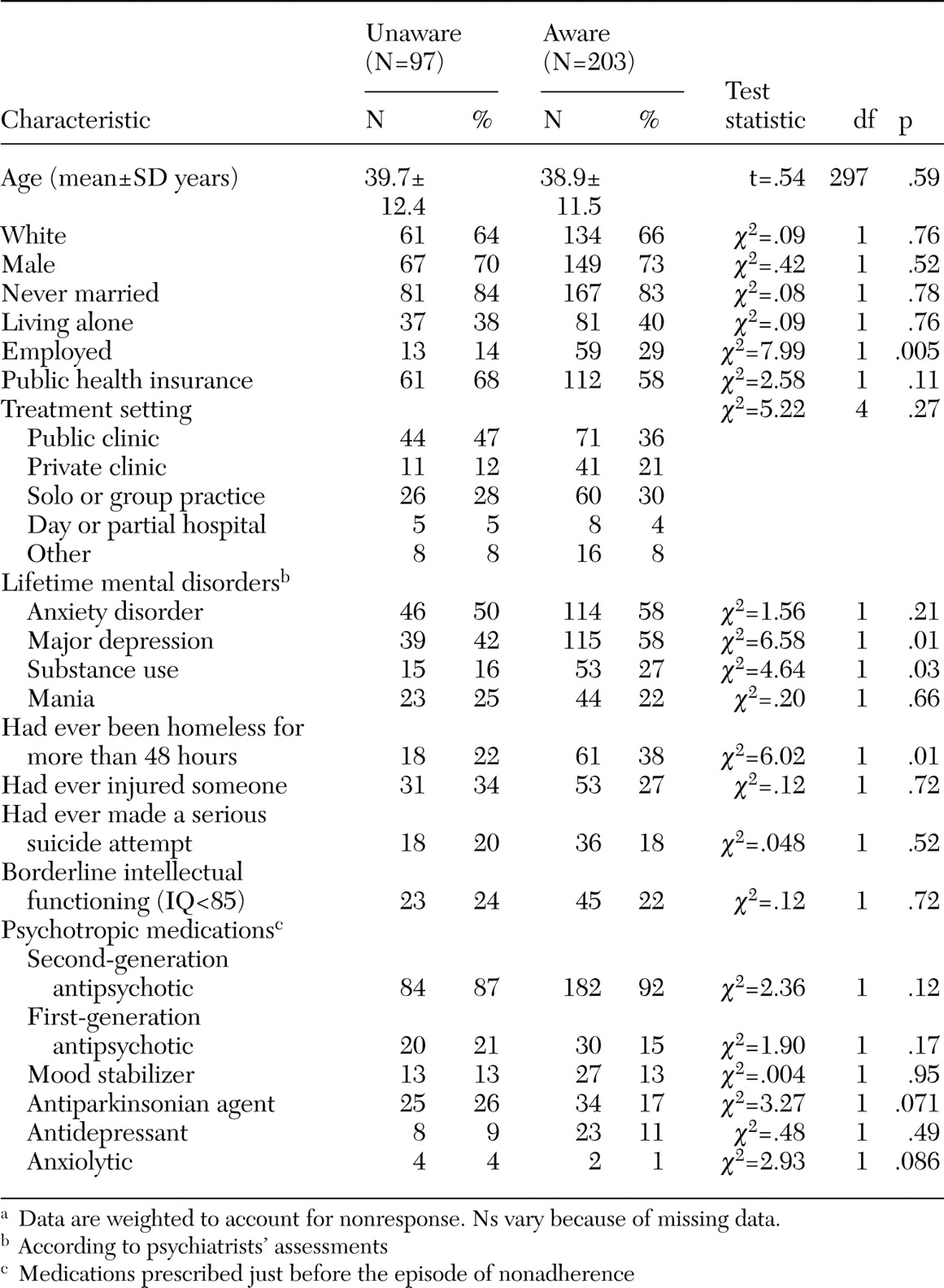

Psychiatrists were asked, in characterizing the selected patients, to determine whether the patient generally believed he or she had a mental illness. This item was used to define the two study groups: patients who were aware that they had a mental illness and those who were not. Data were missing for ten patients for this variable.

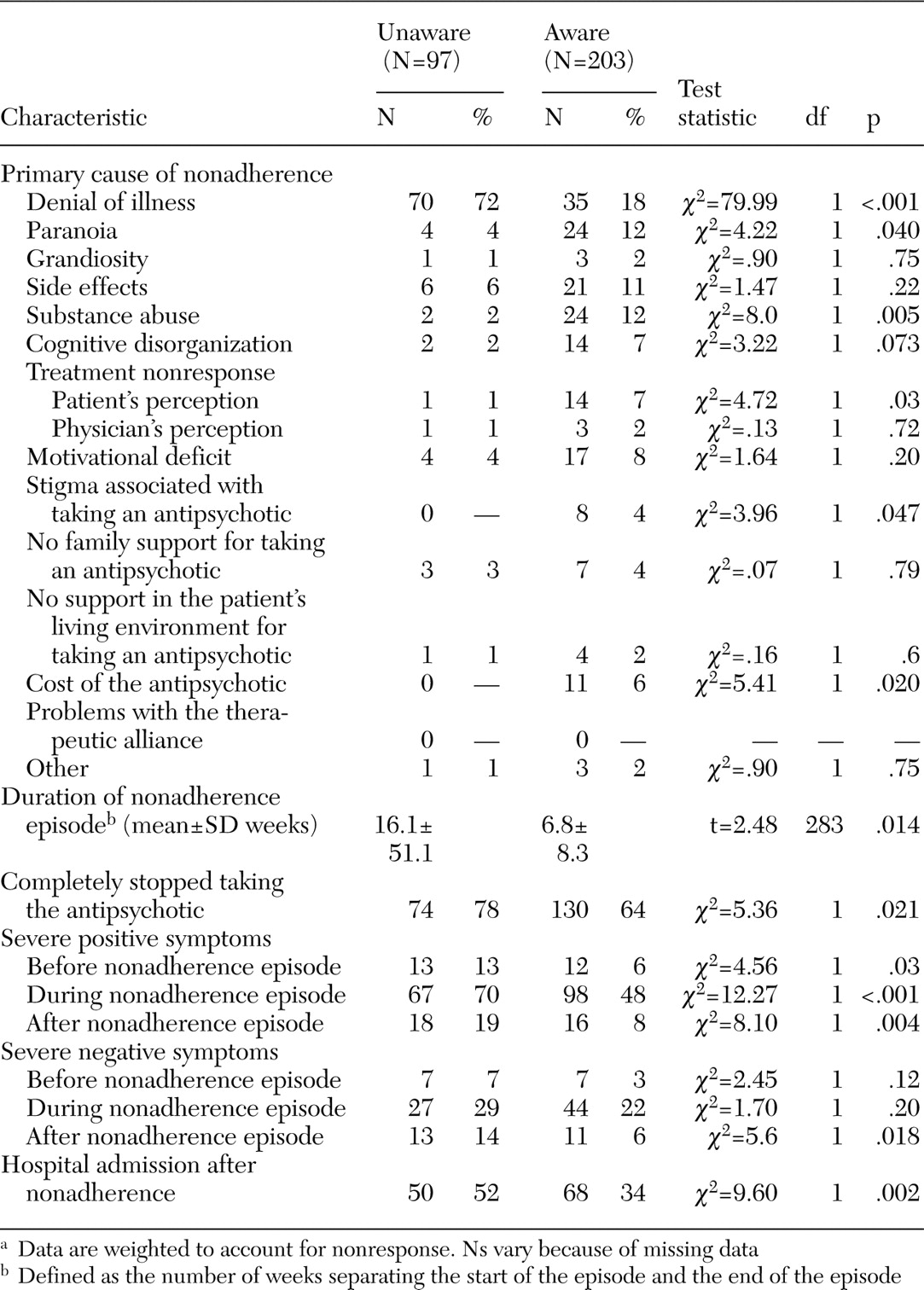

Psychiatrists' assessments of patients who were and were not aware of their illness were compared in terms of basic sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, including selected lifetime mental disorders and prescribed psychotropic medications. The study groups were also compared in terms of the perceived primary cause of the patient's last episode of medication nonadherence: denial of illness, paranoia, grandiosity, cognitive disorganization (difficulty following a medication regimen), motivation deficits (indifference, apathy), intolerable side effects, nonresponse of symptoms to medications, patient's belief that his or her symptoms did not respond to medications, stigma associated with taking medications, lack of family support for medications, lack of support in the patient's living environment for medications, substance use problems, problems with the therapeutic alliance, and cost of medications.

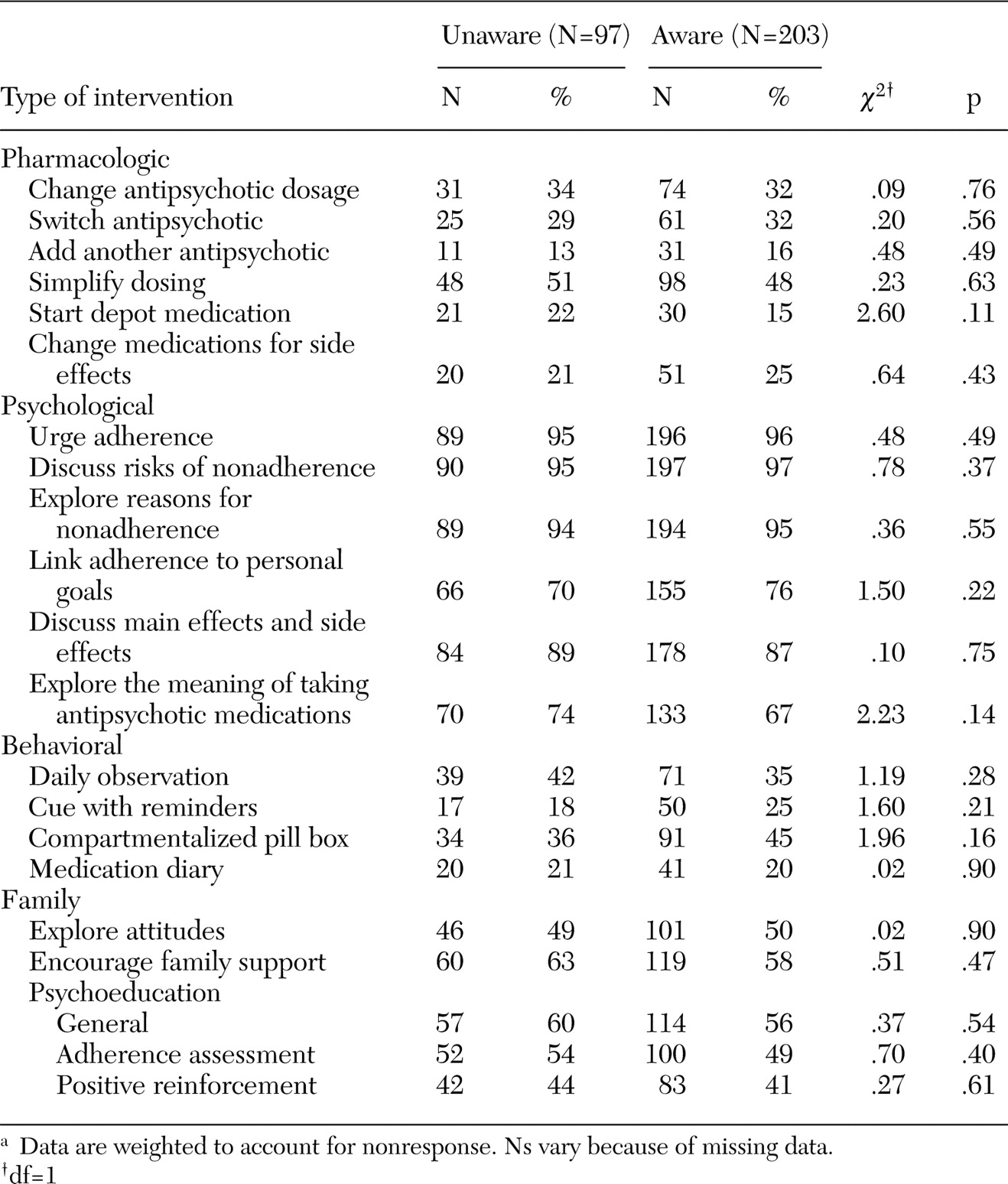

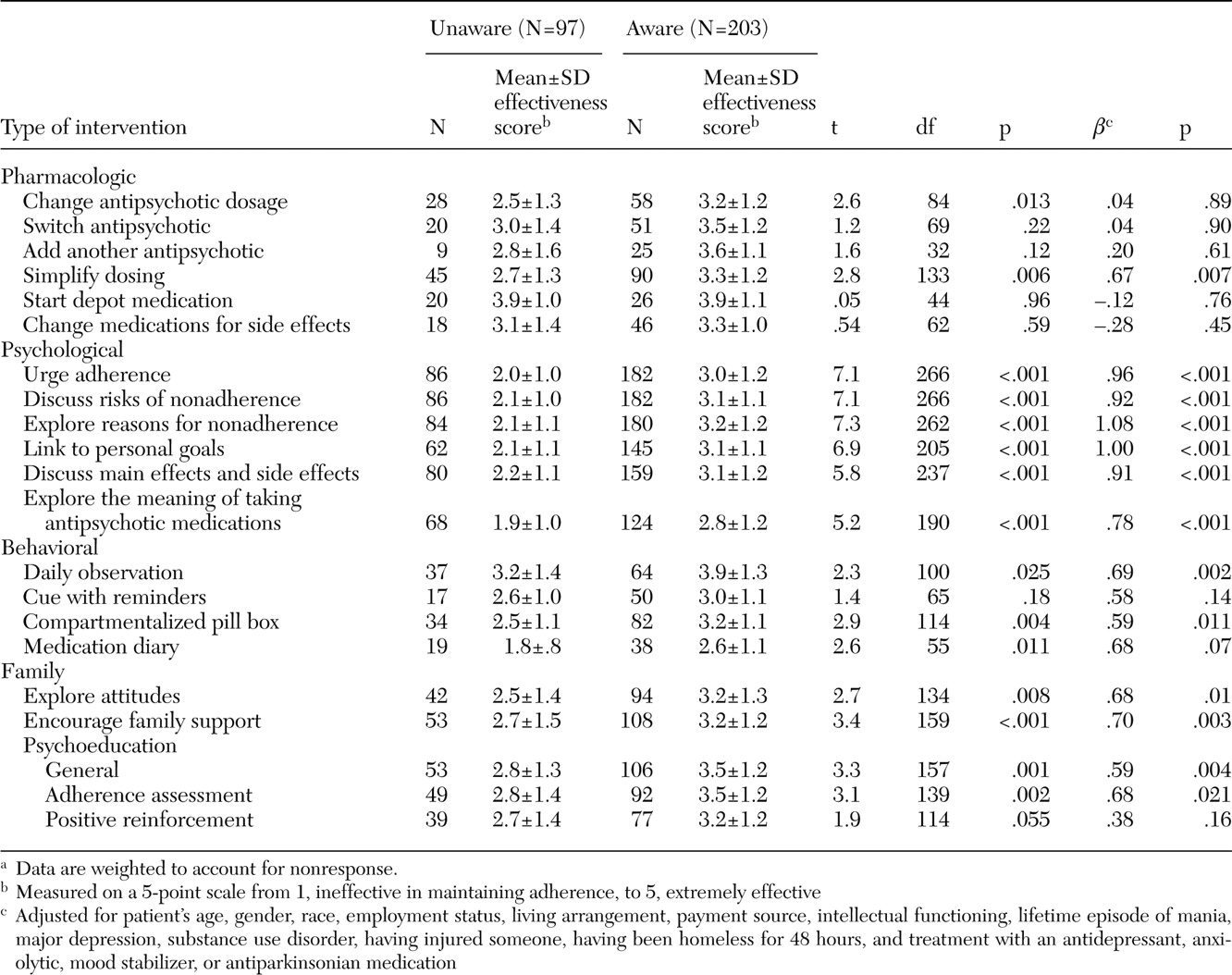

The groups were compared on the frequency and perceived effectiveness of several pharmacologic, psychological, behavioral, and family interventions that were used to manage the most recent episode of nonadherence. For these items, the psychiatrists were asked to indicate whether they used each intervention, and, among those they used, to assess the effectiveness of each on a 5-point scale from 1, ineffective in maintaining adherence, to 5, extremely effective.

Bivariate statistical comparisons were based on chi square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Multiple linear regression analyses examined associations between insight into illness and perceived effectiveness of the intervention, with potentially confounding sociodemographic and clinical patient characteristics controlled for. All analyses included weighting to account for nonresponse.

Discussion

Our findings, in line with previous research (

6,

8,

9), indicate that patients with schizophrenia who are not adherent to antipsychotic medication regimens commonly lack an awareness of having a mental disorder. We estimate that approximately one-third of psychiatric outpatients with schizophrenia in the United States who are nonadherent are not aware that they have a mental illness.

In this study, awareness of illness was related to a history of comorbid depression. A recent meta-analysis also indicated a positive relationship between insight and depressive symptoms (

25). More severe depression has been strongly associated with greater insight early in the course of illness (

26) and among patients with multiple episodes (

27,

28,

29). In one study, insight into illness was related to suicidal ideation (

30). As clinical efforts are made to extend and broaden insight into illness among persons with schizophrenia, it may be important to monitor patients closely for changes in mood state and suicidal behavior (

17).

Patients who were aware of having a mental illness were approximately twice as likely to be engaged in paid or volunteer employment as patients who lacked such awareness. This finding is consistent with previous research linking impairments in insight and occupational performance (

31,

32). In one study of adults with schizophrenia, those with poor insight into their illness had greater difficulties cooperating with coworkers, poorer work habits, and poorer quality of work than their counterparts whose insight was intact (

32). Improvements in vocational rehabilitation have also been related to improved insight (

33).

In this study, a history of substance abuse and homelessness was related to an awareness of illness. Longitudinal research is needed to help define the extent to which awareness of schizophrenia increases vulnerability to substance abuse or housing loss, or whether these adversities tend to lead to a greater awareness of having a mental disorder among individuals with schizophrenia.

Several investigators have reported that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is related to deficits in insight (

32,

34,

35,

36). In our study, which involved comparisons among patients who had recently been nonadherent to medications, awareness of mental illness was not significantly related to general intellectual functioning. Because nonadherence is also significantly related to poor intellectual functioning (

36), it is possible that, because the samples were limited to patients who were nonadherent, group differences in intellectual functioning were attenuated.

Denial of illness was cited as the primary cause of nonadherence for a majority of patients who lacked awareness of their illness. By contrast, paranoia was less commonly related to nonadherence among patients who lacked awareness than among those who were aware of having a mental illness. This finding, together with the lower rates of depressive disorder in the group that lacked insight, is consistent with research linking the evolution of insight to development of depression and paranoia in early-stage schizophrenia (

37).

The consequences of nonadherence to antipsychotic medications may be especially serious for patients who lack awareness of having a mental disorder. Compared with patients with intact insight, patients with impaired insight have a significantly longer duration of nonadherence, are more likely to completely cease taking antipsychotic medications, have more severe positive psychotic symptoms, and are more likely to be psychiatrically hospitalized.

In routine psychiatric practice, management of nonadherence to antipsychotic medications does not appear to vary markedly with awareness of illness. No significant differences were found by illness awareness in the frequency with which patients received a wide range of pharmacologic, psychological, behavioral, and family interventions. Simple psychological interventions, such as urging the patient to maintain medication adherence or discussing the risks of nonadherence, were almost universally provided to both patient groups.

In clinical treatment research, cognitive-behavioral and motivational approaches have shown some promise in building insight (

17) and improving adherence (

18,

19) among persons with psychotic disorders. By contrast, the common—and presumably much less intensive—psychological interventions we assessed in routine practice were perceived as relatively ineffective in managing antipsychotic nonadherence, especially among patients who lacked awareness of having a mental disorder. Differences between patient groups in perceived effectiveness tended to be less evident for several of the pharmacologic interventions.

For both patient groups, starting a depot medication (

38) and observing pill taking on a daily basis were rated as the two most effective interventions. Expanding the use of these interventions might improve the management of nonadherence. At the same time, more work is needed to develop and test intensive psychological approaches to the prevention and management of nonadherence to antipsychotic medications among patients with schizophrenia.

This study had several limitations. First, the data are based exclusively on the psychiatrists' assessments. Although we limited the study to patients who had been under the psychiatrists' care for at least a year and who therefore were presumably well known to the psychiatrists, the absence of patient-reported or family-reported data imposes significant and obvious limitations. For example, patients may have a different view than their psychiatrist of the effectiveness of treatment. In addition, the exclusion of patients who were seen for less than a year is likely to have eliminated many highly nonadherent patients.

Second, the accuracy of clinicians' assessments of adherence to antipsychotic regimens has been questioned (

39,

40). Although a more intrusive method of adherence measurement, such as pill counts, serum levels, and electronic MEMS (Medication Event Monitoring System) caps, would likely have yielded more accurate information, the promise of improved accuracy of measurement must be weighed against substantial selection biases that are likely to have been introduced by limiting the sample to patients who were willing to submit to intrusive adherence monitoring.

Third, illness awareness was measured with a single survey item. A more extensive assessment of insight into illness (

41,

42,

43) would have provided a more informative description. For some patients, illness awareness may fluctuate and cannot be captured by a dichotomous measure.

Fourth, salience of individual cases may have biased patient selection and produced a sample of memorable patients rather than representative patients (

44). Fifth, no information was collected for patients who consistently adhered to their antipsychotic therapy. For this reason, the results do not address patients who, despite reporting that they were not ill, came to appointments and took their antipsychotic medications as prescribed. Finally, survey nonresponse may have biased the reported rates and group associations. Although we adjusted the results for nonresponse related to known characteristics of the study psychiatrists, we cannot exclude the possibility that response patterns related to unmeasured respondent characteristics biased study findings.