According to the

Oxford Dictionary on Historical Principles (

1), humor is “the faculty of perceiving and enjoying what is ludicrous or amusing.” Much literature has described the role of humor in psychotherapy, including several handbooks (

2–

6). Humor’s potential as a psychotherapeutic tool, however, has long been considered controversial (

7,

8). For example, Kubie (

9) was unequivocally against its use in psychoanalysis. He found that humor limited the client’s range of reactions to the therapist’s interpretations and that the therapist’s humor could be used as a defense against the therapist’s own anxiety, as disguised hostility toward clients, or as a seductive interaction. In contrast, most existing literature points out numerous advantages of using humor in an empathic, respectful way during psychotherapy.

Many authors have underscored humor’s potential in reframing a client’s view of the world, with its ability to introduce a new interpretation or new point of view about the presenting problem (

10–

13). This advantage has been highlighted by empirical evidence, demonstrating a correlation between sense of humor and active perspective taking (

14). Concurrently, reframing has been recognized as one of the most frequently used therapeutic tools in a variety of psychotherapy models (

15,

16). Several psychotherapeutic uses of humor are related to the therapist’s ability to use it to reframe clinical situations. For example, by connecting the meaning of the client’s favorite joke to the presenting problem (

17) or by using humor or jokes as metaphors for the present situation (

18).

Additionally, the anxiolytic effects of humor have led to its recognition as one of the most effective coping mechanisms (

19), inspiring therapists to use humor successfully in stressful situations, such as reducing interpersonal tension (

20), working creatively with aggressive clients (

21), and coping with disasters (

22).

Finally, various other therapeutic uses of humor have been described, including communicating indirectly (

23), deflating shame (

24), exposing irrational thinking (

25), developing resilience (

26), and producing verbal communication and contradictory nonverbal signals simultaneously, thereby resolving auto-double-binds (

27). Considerable advice has been offered on effective, non-harmful ways of using humor in therapy (

7,

10).

Recently, attention has focused on the importance of positive dimensions of mental health, such as feeling optimistic, enjoying relationships, and feeling in emotional control, in defining remission from depression. Patients have considered these elements better indicators of remission than absence of depressive symptoms (

28). General practitioners and psychiatrists also rank resumption of pleasure in doing things as most important in defining recovery from depression (

29). Additionally, facilitating change requires keeping the client’s emotional arousal at moderate levels (

30). Thus, the use of humor by therapists could appear to foster these positive elements. However, the following questions remain: Is there any empirical evidence that therapy sessions in which humor is present lead to better outcomes for clients? Are scientific data available that would lead us to advise therapists either to include humor intentionally as a useful therapeutic tool or to avoid it and adopt a serious attitude instead?

To date, researchers have found that humor is associated with various dimensions of the therapeutic process. Depressed individuals have been found to display decreased levels of humor (

31,

32). Nevertheless, clients’ positive reactions to therapists’ humor have been described in severe clinical situations (

33,

34), and appreciation of humor has been shown to persist in a group of 200 patients diagnosed as having depression (

35). Furthermore, the association between humor and therapeutic alliance has been highlighted by clinical experience (

36,

37). This association is particularly interesting because therapeutic alliance is considered “one of the most potent common factors” related to psychotherapy outcomes (

16), and this association is supported by strong empirical evidence (

38,

39).

Despite these overall encouraging findings about the impact of humor, little empirical research has been conducted on the effect of intentionally used humor on psychotherapy outcomes (

2,

40). To the best of our knowledge, the only study dedicated to this purpose (

41) tested humorous versus nonhumorous systematic desensitization among 40 students with arachnophobia. Both therapeutic options were equally effective in reducing fear of spiders, although the authors found that the students treated with the humorous desensitization significantly increased their use of humor as a coping strategy.

The research presented in this article constitutes a first step toward addressing whether the use of humor by therapists in individual outpatient psychotherapy sessions fosters positive patient outcomes. In this study, we analyzed possible associations between the presence of humor during individual outpatient psychotherapy sessions and several psychotherapeutic outcome measures. Other parameters investigated included the association between the presence of humor and therapeutic alliance and severity of patient illness and whether clients and a therapist reported similar experiences regarding these elements of the therapeutic relationship. We then discuss whether, when, and how humor can be useful to the therapeutic process and, ultimately, to client well-being.

Methods

Participants

A total of 110 clients (70 [64%] women and 40 [36%] men) who attended at least 10 psychotherapy sessions were included in this study conducted in Belgium. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Hôpital St. Joseph in Liège. Mean age was 40.8±11.9 (range 20–70 years). All therapy was individual, although couple or family sessions were included for 12 clients, totaling 0.35±1.37 sessions (range 0–10). Two clients had six systemic sessions, one client had five, and eight clients had one to three sessions. Also, one client had 10 systemic sessions, as she was always accompanied by a social worker. The total number of sessions averaged 12.1±4.7 (range 10–38), with 65 clients attending 10 sessions and 45 clients attending more than 10 sessions. Ninety-six clients (87.3%) had a maximum of 14 sessions. Therapy sessions were provided over 335±281 days (range 67–1,837). Missed sessions, defined as sessions not attended by the client and not cancelled 24 hours in advance, were counted in the total number of sessions. The mean number of missed sessions was 0.51±0.9 (range 0–5). Most clients were Caucasian (N=105; 95%), two clients were of Turkish origin, one was of Moroccan origin, one was of Algerian origin, and one was one of Vietnamese origin. Sixty-six percent of the clients were taking antidepressant medication during the study.

All clients were assessed clinically by the first author (C.P.) during therapy sessions according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Diagnoses were major depressive disorder (N=26; 24%), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (N=24; 22%), generalized anxiety disorder (N=3), obsessive-compulsive disorder (N=2), panic disorder with agoraphobia (N=4), panic disorder without agoraphobia (N=2), social phobia (N=3), relationship problems (N=42; 38%), cyclothymia (N=1), substance dependence or abuse (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis) (N=14; 13%), anorexia nervosa (N=3), and brief psychotic disorder (N=4).

Procedure

Between March 2010 and January 2015, new clients reaching the 10th session and current clients who were in therapy for more than 10 sessions were invited to answer a questionnaire as part of a global evaluation of their therapeutic progress. Our purpose was to assess clients within an ongoing therapeutic process, at a point in therapy where it would be possible to evaluate outcomes. We also wanted to measure occurrences of humor, which we believed would be rare. Because the average number of sessions in individual psychotherapy varies from 5.5 (

42) to 22 (

38), we decided to include clients who completed at least 10 sessions. We invited 111 clients to answer the questionnaire. One client declined to participate in the study, a second client declined at session 20, but on his own initiative requested the questionnaire at session 22. For a third client, the invitation to complete the questionnaire was postponed to session 17, because the client had a relapse in acute psychotic symptoms at session 10. All clients were treated by the same therapist (C.P.). Therapy sessions occurred at a hospital outpatient clinic or in private practice in Liège, Belgium.

Data were collected for clients who provided informed consent. The therapist first completed a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

43) measuring depression intensity in the client’s presence. Then, on his or her own in the therapist’s presence, each client completed the Humor in Therapy Questionnaire–Client Version. This 25-item questionnaire was designed specifically for the study and is described below. Meanwhile, the therapist completed Clinical Global Impressions scales (CGI) 1 and 2, which measured clients’ severity of illness and global improvement (

44). The therapist also collected clients’ demographic and clinical data (sex, age, diagnosis, and number of sessions) and searched client file

s for the number of written notes concerning humorous events or laughter episodes. The therapist then answered the Humor in Therapy Questionnaire–Therapist Version (described below). The therapist also retrospectively completed a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale based on the psychotherapy notes from the client’s first session. When information was missing, a conservative method was applied, using the answers from the Hamilton scale completed by the therapist during the 10th session to fill in the missing items. Filling out the Hamilton scales, CGI, and questionnaires usually lasted no more than 15 minutes, within a 45-minute session. Clients were assured that no identifying data would be used during the statistical analysis or publication of the material. Results of the questionnaires were discussed individually with clients in subsequent sessions to provide feedback about their evaluation and provide the therapist’s evaluation of therapy effectiveness and therapeutic alliance, with the purpose of enhancing outcomes (

42). All clients provided informed consent to include the results in their therapy files.

Measures

The 17-item Hamilton Depression scale was selected for its sensitivity to assess change in depression intensity and for its multidimensional nature. In this scale, depression is considered to be absent, 0-7; low, 8–17; moderate, 18–25; or severe, 26–52. The CGI-1 was used to measure severity of illness (ranging from 1, normal, not at all ill, to 7, extremely ill) at the time of the study (10

th session or beyond). The CGI-2 was used to evaluate the client’s global improvement (ranging from 1, very much improved, to 7, very much worse) (

44).

The Humor in Therapy Questionnaire–Client Version was designed with three sections assessing 25 items. Section A consisted of nine items focused on global satisfaction with therapy, including two items assessing therapy effectiveness, two assessing hope, three assessing therapeutic alliance, and two assessing pleasure in participating in therapy sessions. Section B consisted of 12 items focused on the presence of humor during therapy sessions, assessing the frequency and intensity of the client’s ability to see humor in the situation, client-initiated humor, therapist-initiated humor, client laughter, and therapist laughter. One item addressed the frequency of shared laughter, and one item addressed the frequency of shared word play. Section C covered additional data not used for the current article. Section D consisted of four items assessing the client’s beliefs about the usefulness of humor during therapy. Four of the 25 items were reverse-keyed (16.0%). The Humor in Therapy Questionnaire–Therapist Version was composed of the same 25 items (sections A, B, and D) as the client version, but was adapted to collect the therapist’s perspective. Clients and therapist rated their answers on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, completely disagree, to 4, completely agree. After pilot testing of the questionnaire with three clients and four family members, annotations were adapted for clarification, especially for the reverse-keyed items.

For illustrative purposes, some sample questions for each section follow: section A, “Do you think this therapy is effective to solve the problem that led you to consultation?” (effectiveness); section B, “How often did you initiate humor yourself or tell a joke, or say something funny during your therapy?” (frequency of client-initiated humor); section D, “Did the humor and laughing moments that occurred during your therapy contribute to the hope you are experiencing today?” (client’s beliefs about humor usefulness).

Outcome Measures

The Hamilton score at session 10 (or later) was subtracted from the score at session 1 to obtain the Hamilton difference score. The other outcome measures were CGI-2 results, client’s rating of therapy effectiveness, therapist’s rating of therapy effectiveness, client’s global satisfaction with therapy (range 0-36, obtained by totaling the scores of section A of the Humor in Therapy Questionnaire, effectiveness [range 0–8], hope [0–8], therapeutic alliance [0–12], and pleasure in participating in therapy sessions [0–8]). The therapist’s global satisfaction with therapy was obtained by totaling the therapist’s scores on section A, using the same procedure.

Humorous Interventions

While spontaneous humor was allowed during sessions, aggressive humor was avoided to protect the therapeutic alliance. Humorous interventions were used only if clinically appropriate, taking into account the client’s situation, personality, and presenting problem. Various humorous techniques were used—e.g., exaggeration of the client’s ideas and behavior (

33), expressing nonverbalized or implicit client thoughts (

36), asking about the client’s favorite joke (

17), using jokes as metaphors (

18), and giving the client a humorous, provocative, nickname (

45). Identifying characteristics have been modified to protect client confidentiality in the following two examples.

Clinical example of client humor.

A 55-year-old homosexual client with low self-esteem and chronic health issues once more describes his long-standing couple conflicts. He feels his partner is abusing him financially and emotionally. He then suddenly concludes, “Because of the fact that I’m living with Satan, my health is in a hell of a state!!” The client bursts out laughing and adds, with a malicious smile, “I love myself!” The therapist smiled at this example of humorous word play.

Clinical example of therapist humor.

A 30-year-old woman experiencing a happy, new couple relationship wonders if she wants another child. She feels guilty she had her first son “with the wrong father,” who turned out to be violent.

Client: “I don’t know if I want to have another baby: I’m afraid that this child would be a way of rectifying my mistake.... And that wouldn’t be good for the baby!”

Therapist (suddenly inspired): “And then you name him after Jesus!!” (Client and therapist laugh together and continue to analyze potential consequences of the client’s decisions).

Statistical Analyses

Results were expressed as means and standard deviations for quantitative variables and as counts and proportions (%) for qualitative variables. We compared Hamilton scores measured at the first and 10th sessions with paired Student’s t tests. We created two subgroups of clients based on their ratings of the therapist’s humor, less funny or more funny. We compared mean values of outcome measures of these two subgroups with an unpaired Student’s t test, and then compared these two mean values to the mean values of the whole sample using a one-sample t test. We categorized clients into two subgroups according to their CGI-1 scores, from 1, not at all ill, to 3, mildly ill, and from 4, moderately ill, to 7, among the most extremely ill. Hamilton subgroups were <8, no depression; 8–17, low depression; >17, moderate. A fourth subgroup consisted of clients with any depression (score >7). We compared humor scores between these subgroups of clients through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by multiple comparisons as necessary. Because several measures of therapy outcome did not follow a Gaussian distribution, we assessed their association with humor scores by using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs). All results were considered significant at the 5% critical value (p<0.05). Statistical analyses were carried out with Statistica 12.

Results

Presence of Humor

To investigate a possible association between humor and therapy outcome, our first step was to confirm the presence of humor within the therapy sessions for these 110 clients. The presence of humor during therapy sessions was determined by the ratings of the client (22.4±8.4 points; range 2–44) and the therapist (19.4±8.4 points; range 0–34) on section B of the Humor in Therapy Questionnaire. The maximum score on the humor section was 48 and would have corresponded to sessions in which each type of humor event was present more than 10 times in every session and was rated as “very funny” every time. If this maximum score had been reached, we might have interpreted this score as a manic symptom of the client and perhaps also of the therapist! Consequently, the mean humor scores reported in this article can be considered moderate to high. The therapist’s psychotherapy notes about meaningful humorous events confirmed the presence of humor, with a mean of 1.2±1.5 notes per client (range 0–7). Client and therapist ratings of the presence of humor showed a significant positive correlation (rs=0.46; p<0.001), demonstrating that the concept of humor had good consistency within the questionnaire. Humor scores were not influenced by the number of sessions for either client (rs=–0.07; p=0.46) or therapist ratings (rs=–0.02; p=0.80).

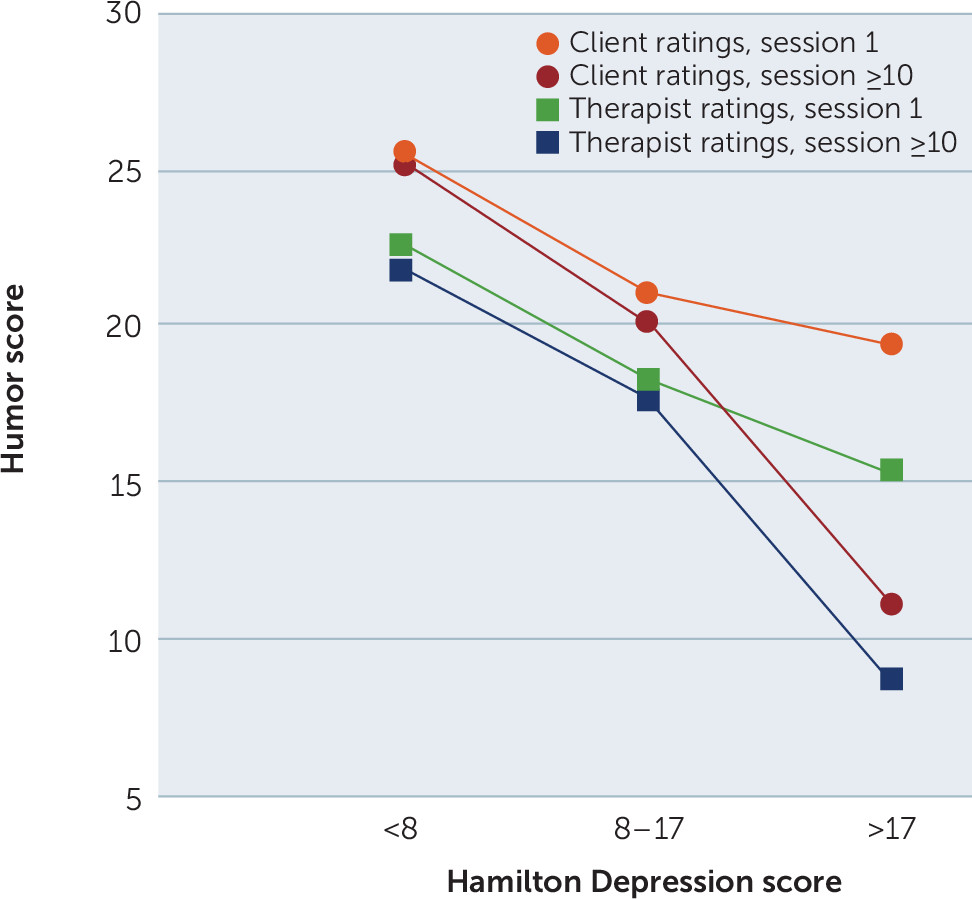

Mean humor scores were significantly lower for clients with more severe CGI-1 scores and with more severe Hamilton Depression scores at session 10 or later (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). For CGI-1 subgroups, client-rated humor scores and therapist-rated humor scores differed significantly (p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). For first-session Hamilton subgroups, based on client-rated mean humor scores, only the groups scoring <8 points and 8–17 points differed significantly from each other (p=0.032). Based on therapist-rated mean humor scores, the group scoring <8 points differed significantly from the group scoring 8–17 points (p=0.044) and from the group scoring >17 points (p=0.015), but the group scoring 8–17 points did not significantly differ from the group scoring >17 points (p=0.45). For Hamilton subgroups at session 10, all three groups differed significantly from each other, from both client and therapist perspectives (all p<0.03) (data not shown).

Client-rated humor scores were negatively correlated with CGI-1 scores (rs=–0.42; p<0.001), as well as with session 1 Hamilton scores (rs=–0.29; p=0.002) and with session 10 Hamilton scores (rs=–0.38; p<0.001). Therapist humor scores also were negatively correlated with CGI-1 scores (rs=–0.25; p=0.009) and first- (rs=–0.30; p=0.002) and 10th-session Hamilton scores (rs=–0.36; p<0.001) (data not shown).

Mean ratings of the 12 items composing the humor section of the Humor in Therapy Questionnaire varied from 1.2±1.1 to 2.7±1.0, establishing the presence of client- and therapist-initiated humor. The association between client and therapist beliefs about the usefulness of humor in therapy was not strong (rs=0.21; p=0.026). Client beliefs about the usefulness of humor were positively correlated with client ratings of the presence of humor during therapy (rs=0.42; p<0.001), but the link was weaker from the therapist’s perspective (rs=0.27; p=0.004) (data not shown).

Client Improvement

Our second step was to assess for the presence of a positive therapy outcome. Clients’ mean ratings of therapy effectiveness were 5.3±1.8 (range 1–8) (

Table 2), whereas therapist ratings averaged 4.6±2.0 (range 0–8). Client global satisfaction toward therapy (addition of section A scores: alliance, therapy effectiveness, hope, and pleasure in participating in therapy sessions) totaled 26.6±5.6 (range 9–36), whereas that of the therapist reached 25.0±6.2 (range 6–36). Hamilton scores significantly decreased (p<0.001) from 10.8±5.8 (range 1–29) at session 1 to 7.9±5.2 (range 0–23) at session 10 or later, which accounted for a Hamilton difference score of 2.9±3.1 (range –7 to 12 points) (

Table 2). Ten clients (9%) obtained a negative Hamilton difference. The mean number of missing items on the session 1 Hamilton scale was 8.7±4.8 (range 0–17 items). Severity of illness at session 10 assessed by CGI-1 scores averaged 3.2±1.1 (range 1–6), and global improvement CGI-2 scores averaged 2.7±0.8 (range 1–6). A positive correlation was found between client and therapist ratings of therapy effectiveness (r

s=0.38; p<0.001) and between client and therapist overall satisfaction with therapy (r

s=0.42; p<0.001). No association was found between number of sessions and measures of therapy outcomes, except for therapist ratings of hope (r

s=–0.23; p=0.01), with fewer sessions correlating with higher therapist hope scores.

Humor and Therapy Outcome

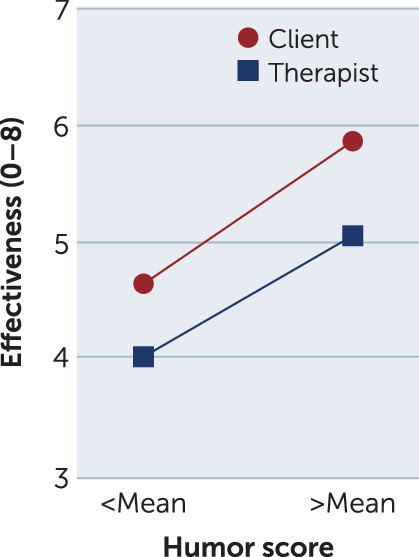

Spearman correlations between client and therapist ratings of the presence of humor during therapy and seven therapy outcome measures are shown (

Table 3). A positive correlation was found between ratings of the presence of humor during therapy and scores for effectiveness (

Figure 2), alliance, hope, and pleasure participating in therapy sessions and with the sum of these scores (global satisfaction with therapy). Additionally, a negative correlation was found with CGI-2 score (note that this scale attributes higher scores to a worsening of the client’s state; the negative correlation is consequently congruent with the positive correlations of the other outcome measures). No correlation was found with Hamilton difference scores. When we considered only the 96 clients who attended a maximum of 14 sessions, results were nearly identical (data not shown).

Multiple regression analysis between session 10 Hamilton scores and client ratings of the presence of humor during sessions showed a significant negative association between both parameters when adjusted for session 1 Hamilton scores (p<0.001). The same pattern was observed as seen from the therapist’s perspective (p<0.01) (data not shown).

These associations were confirmed by the measures noted in section D, addressing client beliefs about the influence of humor on global satisfaction with therapy (3.2±1.1; 4 maximum) and client beliefs about the power of humor to increase hope in therapy (2.2±1.2; 4 maximum). Therapist beliefs about the influence of humor on his own overall satisfaction with therapy (3.7±0.7) and on increasing client hope (3.4±1) also confirmed these findings. Moreover, multiple regression analysis showed that the positive association between client ratings of the presence of humor during sessions and client ratings of effectiveness, alliance, hope, pleasure, and global satisfaction scores remained significant in the presence of antidepressant medication (all p<0.001). The same results were seen from the therapist’s perspective.

To investigate whether use of humor by the therapist was associated with lower outcome scores, we analyzed the subgroup of clients who reported a high frequency of therapist-initiated humor (score >2; 4 maximum; N=45) (

Table 2). In this subgroup, we compared clients who rated the therapist’s humor as less funny (score 0–2; N=11) with those who rated it as more funny (score 3–4; N=34). Hope and pleasure scores were lower in the group that rated their therapist as less funny, but the results remained similar to the whole sample of 110 clients. Moreover, global satisfaction, effectiveness, and alliance scores showed insignificant differences and were higher than those of the entire sample. The results in the group that rated their therapist as less funny did not differ significantly from the whole sample, except for the Hamilton difference score, which was 0.74 lower than that of the total sample (p=0.047). Similar results were obtained from the therapist’s perspective (data not shown).

Relationship with Severity of Client Illness

We then examined whether the correlation between client- and therapist-rated effectiveness and humor scores would differ according to the client’s severity of illness (

Table 1). The positive association between humor and effectiveness disappeared for clients with less severe CGI-1 scores (severity of illness as measured at session 10). However, a positive association remained for worse CGI-1 scores, although these clients reported less humor in their therapy sessions. At session 1, the association was not observed for clients with Hamilton scores <8 but remained positive for clients with Hamilton scores >7 and 8–17; it also remained positive for Hamilton scores >17 but only from the therapist’s perspective. At session 10, from both client and therapist perspectives, the association remained positive for clients with Hamilton scores >7, and only a trend was observed for Hamilton scores of 8–17. From the client perspective only, the association remained positive for Hamilton scores <8.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study of the relationship between the presence of humor in therapy sessions and outcomes in a population of clients attending outpatient psychotherapy sessions that shows a correlation between these two parameters. The 110 participants were men and women, of differing ages, with a variety of diagnoses and clinical problems and a wide range of personal involvement in resolving them. Although the number of diagnoses corresponding to psychosis was low, this sample can be considered a typical population encountered in psychiatric consultation. In contrast, previous research analyzed a population of undergraduate students, almost exclusively women, and focused on the specific diagnosis of arachnophobia (

41).

Our results show the presence of client-initiated and therapist-initiated humor during psychotherapy sessions. Although some of these humorous events could have been misunderstood by the client or the therapist as being serious (

46), we assumed that most of these humorous events were shared and understood by both sides. Indeed, we found a significant correlation between client and therapist humor ratings. Client improvement during therapy also was clearly established, allowing analysis of the relationship between humor and outcome. Correlations between client and therapist ratings of effectiveness, however, were only moderate, showing that the clients and therapist only partially shared the goals of therapy.

A strong positive association was observed between presence of humor during therapy sessions and various measures of therapy outcome, from both client and therapist viewpoints. While humor is not the only parameter associated with outcomes, these results suggest it may be one of them. The absence of a correlation between humor and Hamilton difference was probably due to the large amount of missing information in the retrospectively filled out first-session Hamilton measure (8.1±4.9, of 17 items), thereby limiting the Hamilton score at the beginning of therapy, and consequently lowering the Hamilton difference scores. However, the multiple regression analysis showed a significant negative association between humor and 10th-session Hamilton scores, even adjusted for the first-session Hamilton score, thus confirming the association between humor and outcome.

Humor and Outcome

The correlational design of this study does not allow us to determine the direction of causality between global humor scores and outcome. A first conclusion of the study could be that humor improves therapy outcomes. This is not a surprising finding because features of positive mental health, such as optimism, general sense of well-being, or participating in and enjoying relationships with family and friends, are rated by depressed clients as crucial factors in remission of depression (

28). The association between humor and pleasure in participating in therapy sessions could also be interpreted in this way. Another explanation could be that when clients reach some of their goals in therapy, presence of humor increases. When therapy is acknowledged as effective, the anxiety inherent in addressing the client’s problems lowers, and this lowering may allow client and therapist to engage in more humorous interactions. For therapists, humor would then have a diagnostic value: occurrence of humor would indicate therapy effectiveness. Both of these factors probably contribute to the association between the use of humor in therapy and patient outcomes. Our results replicate the findings of Sala et al. (

47), who found that humor was associated with patient satisfaction in the context of the physician-patient relationship.

Therapeutic Humor

Table 1 shows classic lowering of the use and appreciation of humor in clients with more severe illness. This finding has been observed in populations of both adolescent (

48) and adult psychiatric inpatients (

31,

32). Our results confirmed these findings in a population of adult outpatients and used other clinical scales of humor and severity of illness. In our study, the correlation between humor and effectiveness remained significant for clients with more severe CGI-1 and Hamilton scores, although these clients experienced less humor in their therapy sessions (

Table 1). The correlation disappeared among clients with less severe CGI-1 scores and in the no-depression first-session Hamilton group, where humor scores were higher. A globally similar pattern was observed in the session 10 Hamilton score groups, except for the persisting correlation observed in the group without depression, as rated by the clients.

These findings show that not all humorous interventions are related to therapy effectiveness, but probably only those tailored for the clinical context and aimed at the presenting problem. When therapy is effective and the client exhibits fewer symptoms of depression, the greater amount of humor experienced then corresponds in part to an increase of two subtypes of humor. The first of these is affiliative humor that is not directly related to the client’s clinical situation. This type of social humor remains useful to lower the anxiety generated by therapy, and to maintain the therapeutic alliance, but is probably less related to therapy outcome. The second subtype is “avoidance humor,” which allows clients to escape being confronted with the core issues of therapy (

20,

27,

48). Our clinical impression is that depressed clients use avoidance humor less and that this type of humor often reappears during therapy as clients present fewer symptoms of depression. The increased presence of these two subtypes of humor in clients with less severe illness could explain why the correlation between humor and therapy effectiveness disappears in some of these client subgroups.

Not all types of therapist humor enhance the therapeutic process, however. Every humorous remark aimed at reframing a clinical situation must simultaneously foster the therapeutic alliance by transmitting the therapist’s empathy and comprehension of the client’s dilemma (

49). Farrelly and Brandsma (

33) underscored that provocative interventions can be harmful if the client does not laugh at some moments during therapy. The client’s genuine laughter confirms his or her understanding of the therapist’s empathy and benevolence. Indeed, humor also can distract the therapist, causing the therapist to focus on his or her own feelings, rather than concentrating on the client’s experience of therapy. One example of this phenomenon is the use of hostile humor by the therapist (

7). Therefore, the therapist needs to focus continuously—even more so during the humorous moments of therapy—on therapeutic alliance and on the client’s nonverbal expressions of hope and pleasure (

50).

We also wanted to know whether clients who reported a high frequency of therapist-initiated humor and rated these humorous interventions as less funny would display lower scores on outcome measures (

Table 2). The results showed that when humorous interventions were perceived as less funny, they were associated with lower hope and pleasure scores. Again, the direction of causality could not be proven by this correlational study. Hope and pleasure can be enhanced by humorous interventions or they can increase the perceived funniness of the therapist’s humor. However, when we compared the seven mean outcome values to the whole sample, no important lowering in outcomes was observed among clients who perceived their therapist as less funny. In fact, most outcome values were higher (albeit insignificantly) in this subgroup. The Hamilton difference showed a significant, although modest, lowering of 0.74. In this subgroup of clients who perceived their therapist as less funny, however, the amount of missing information for the retroactively filled out session 1 Hamilton scale was particularly high, averaging 13.00±2.45 of 17 items, considerably limiting the impact of this finding. In sum, our results showed no harmful effects of humorous interventions on the clients in the present study. Our results thus confirm the results of Megdell (

46), who showed no decrease in clients’ attraction to counselors when humorous interventions were either not identified or not rated as humorous by the clients.

Limitations

Because only clients demonstrating a significant therapeutic alliance would probably attend more than 10 sessions, this inclusion criterion may have selected for clients with more positive outcomes (

16). This criterion excluded clients terminating therapy after fewer than 10 sessions. These clients mostly attended a single session (

42), in which an effective therapeutic alliance could not be established, thus resulting in a poor outcome. This criterion also excluded successful therapies terminated in fewer than 10 sessions. Nevertheless, the range of client and therapist ratings of therapy effectiveness, overall satisfaction toward therapy, and Hamilton difference scores showed that our sample also included clients with poor outcomes at the time of the questionnaire.

In our study, all therapy sessions were conducted by the same therapist, a white man in his late 30s, trained in systemic family therapy and familiar with provocative therapy. Consequently, results are limited to the therapeutic style and clinical contact of this therapist and do not represent the variety of styles clients may encounter from their therapist. The kind of humor used in this study surely differed, for example, from that of a 65-year-old female therapist of Asian origin, with a psychoanalytic background. But even if humorous interventions were adapted to the personal problem and personality of each client—and undoubtedly evolved over time due to training and clinical experience—this study offers the opportunity to analyze a coherent and globally uniform way of using humor in psychotherapy, avoiding the problem of therapist variability (

30). However, before we can generalize these results, they should be replicated with therapists of differing ages, backgrounds, and clinical styles and with a larger client population.

This study was limited by its global assessment of humor, without regard for the specificity of humorous interventions. Clinical interventions, whether humorous or not, need to be specific for the actual situation, perspective, therapeutic alliance, and process of each client.

Future Directions

Given the well-documented association between therapeutic alliance and therapy outcome (

38), clinical experience suggesting that humor may enhance therapeutic alliance (

37), and our results showing a positive correlation between humor and alliance, the relationship between humor and alliance should be studied more thoroughly. Our questionnaire was short because it needed to be completed within a 45-minute therapy session. It contained only three items analyzing the three dimensions of the therapeutic alliance: agreement on tasks and goals of therapy and the emotional bond between client and therapist (

38). Further studies of the link between humor and therapeutic alliance should use alliance scales that allow for differences in these three dimensions (

51).

Considering the growing evidence concerning the influence of humor on psychological well-being, it would be beneficial to analyze the role of client and therapist humor styles on therapy effectiveness. Self-enhancing humor and affiliative humor have been shown to have positive associations with self-esteem and psychological well-being. They also are negatively related to depression and anxiety, whereas self-defeating humor is positively correlated with depression, anxiety, and psychiatric symptoms (

52). Besides the classic advice of discouraging overt aggressive humor toward clients, other types of humor may have potential therapeutic value, depending on the clinical situation (

49).

Finally, because this was a correlational study, we did not address the causality of the link between humor and therapy outcome. In the future, single-blind studies comparing two cohorts of clients randomly assigned to normal therapy versus humorous therapy should be evaluated. Incidentally, we would certainly smile on any heroic attempt to evaluate double-blind procedures, which would demonstrate a novel kind of humor style by the researchers themselves.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Vassilis Saroglou for his advice in building the questionnaire; Véronique Jacques, Johnny Piette, Francis Panichelli, and Stéphanie Panichelli-Batalla for their comments on the questionnaire; and Tyler Marshall for “polishing” the English manuscript.