In recent years, remarkable advances have occurred in remote communication technologies that have the potential to address unmet needs in underserved populations through telehealth services. The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly accelerated these advances. Although social distancing, isolation, and quarantine are the primary public health strategies to mitigate the pandemic, these measures impede access to social support and mental health care and potentially elevate risk for worsening psychiatric distress (

1–

3). The present study was intended to explore participant engagement in and acceptability of a group parenting intervention adapted to a video telehealth format after emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic and its academic, recreational, and financial consequences, as well as resulting social isolation and challenges caused by quarantines and lockdowns, pose a uniquely burdensome situation for vulnerable parents and other primary caregivers (

3). In a nationally representative sample, a majority of mothers reported worsening mental health because of the pandemic in March 2020 (

4), with other recent findings linking caregiver burden and psychiatric distress with conflict in the parent-child relationship (

5) and indicating a correlation between worsening parental mental health and children’s behavioral challenges (

6). These family impacts are likely to be disproportionately pronounced among minority and underserved communities, where the pandemic has exacerbated existing health and economic disparities (

7–

10). Caregivers of children with mental health challenges in diverse and underserved communities have thus faced the cascading stressors of meeting their children’s needs for support in the context of constrained access to their own social or mental health support, increased health and financial concerns, and ongoing exposure to discrimination and structural marginalization.

Since the rapid and widespread transition to telehealth services during the pandemic, researchers have begun to evaluate the opportunities posed by this alternate delivery format, emphasizing its potential in the midst of the ongoing crisis to provide innovative and meaningful forms of support to patients and families and to increase access to care among hard-to-reach populations (

11–

13). The benefits of telehealth, including decreased costs and increased access to care, were recognized before COVID-19 (

14,

15). The increasingly broad and diverse evidence base for the effectiveness of telehealth extends to treatment for depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress (

16–

21) and to group as well as individual formats (

22–

25). A review of studies delivering evidence-based psychotherapies via video telehealth (

15) found outcomes mostly comparable with in-person treatment, as well as preliminary support for cost-effectiveness, patient and provider acceptance, and safety.

Research focused specifically on group teletherapy has reported similar acceptability. A recent review (

14) of group interventions delivered via videoconferencing to provide psychoeducation, social support, or both to populations in primary care or with chronic illness concluded that the format is conducive to supporting therapeutic group processes, such as cohesiveness, and is acceptable even for those with limited digital literacy. Similar outcomes have been reported for group psychotherapy studies comparing in-person and videoconferencing groups intended to treat mood, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorders (

24), despite some participants expressing preference for in-person groups (

14,

25). Collectively, these findings suggest that group therapies delivered by videoconferencing are generally acceptable to patients and have the potential to improve treatment accessibility.

The current pilot study sought to examine whether the telehealth adaptation of a group parenting intervention could establish and maintain prepandemic levels of patient acceptability and treatment engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, in an underserved urban community particularly affected by the pandemic. Potential challenges to successful telehealth transitions highlighted by investigators (

26–

29) have included technological literacy, adaptation of the therapeutic intervention, issues related to patient privacy and confidentiality, and cultivation of the therapeutic alliance. However, research has also documented associations between unmet social needs and barriers to in-person appointment attendance, with a recent study within a large urban health care system (

30) finding that transportation needs may present a particularly burdensome barrier for patients in underserved communities. Research (

31) has also shown that parent-perceived stressors and obstacles associated with treatment act as barriers to outpatient child therapy. The transition to telehealth services made requisite by the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to explore the acceptability of and engagement in this mode of service delivery in an understudied population: caregivers within a diverse, urban community.

Therapeutic approaches, such as mentalizing-focused interventions, that are transdiagnostic, flexible, and capable of addressing the pandemic-related challenges faced by vulnerable families seem well poised to facilitate meaningful, effective work via telehealth (

10). Mentalizing refers to the capacity to understand ourselves and others as motivated by underlying mental states, such as feelings, thoughts, desires, goals, and attitudes (

32). Parenting interventions that target mentalizing offer an adaptable and integrative approach to support parents’ capacity to recognize and modulate negative affect during stressful parent-child interactions and other challenging contexts (

10,

33). Mentalizing-focused interventions have been shown to be effective in promoting sensitive caregiving, positive parent-child interaction, and child attachment security (

34). This therapeutic framework, which foregrounds curiosity, openness to new or alternate perspectives, reflection, and restoration of emotion regulation, is well suited to supporting families during times of crisis and lends itself naturally to modification in service delivery because of its flexibility.

Despite a growing evidence base for the effectiveness of mentalizing-focused parenting interventions, to our knowledge this is the first outcomes report of a mentalizing-focused parenting intervention delivered via telehealth. The primary aims of this prospective pilot study were to compare treatment engagement, as shown by attendance and no-show rates as well as active participation and duration of attendance during sessions, before and after the transition to telehealth, and to examine therapeutic efficacy, as shown by changes in participant-reported mood and anxiety symptoms. The secondary aims were to explore treatment acceptability through participant reports of therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, and concerns about privacy related to the telehealth platform.

We hypothesized that the transition to telehealth would lead to decreased no-show rates and a nonsignificant change in within-session participation and duration of attendance. We further hypothesized that participation in the mentalizing-focused groups adapted to the telehealth format would be associated with significant decreases in self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms. Finally, we hypothesized that participants would find the mentalizing-focused group treatment to be acceptable when delivered in the video telehealth format, as reflected in high levels of self-reported group cohesion and group leader alliance.

Methods

Sample

The Connecting and Reflecting Experience (CARE) program is a group parenting intervention designed to support secure parent-child attachment relationships by fostering parental mentalizing. The 12-session, transdiagnostic, bigenerational program is designed for primary caregivers of children from birth to 18 years and is based in a child outpatient community mental health clinic. Caregivers who have reported high levels of parenting stress or who have demonstrated difficulty in understanding their child or themselves as parents are referred to the program by child therapists within the clinic or by other providers within the health system. The intervention is delivered in hour-long weekly sessions by licensed clinical psychologists, postdoctoral fellows, predoctoral psychology interns, and social workers who receive onsite training and weekly supervision in attachment theory, developmental psychopathology, and mentalizing-focused treatment.

As a group-based adaptation of Mothering From the Inside Out (

33), CARE shares its core treatment objectives of building and maintaining the therapeutic alliance, promoting the caregiver’s ability to mentalize for herself and for her child, maintaining a mentalizing stance, and providing attachment-informed developmental guidance. Sessions focus on fostering a process rather than on delivering specific content. The group-based approach anticipates the challenges of resource limitations within underserved communities facing health disparities by supporting the development of social connections among group members (

35). Program participants are given the option of continuing to attend the group after their 12th session.

Although CARE groups are typically composed of six members, the size of the groups in the current study were limited by the inability to enroll new group members during the clinic’s transition to telehealth services during the early weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown. Thus, the sample (N=12) for this study included all members of three ongoing CARE groups that had been initially delivered in person and had shifted to telehealth; all participants had completed their 12th session before the transition. Group members began attending weekly video telehealth group sessions via a HIPAA-compliant platform after the clinic’s transition to telehealth services during the pandemic, which occurred 5–6 weeks after their last in-person session. Data were collected between January and August 2020.

Inclusion criteria were previous enrollment and ongoing participation in an in-person CARE group. Participation at the time of implementation required that individuals be English-speaking and the primary caregiver of a child receiving services in the outpatient clinic. The only exclusion criterion was lack of a device with the capability to connect via audio to the telehealth platform. However, all eligible CARE group members possessed a suitable device and were thus able to participate in the current study; no caregivers were excluded or declined to participate.

Procedure

Caregivers enrolled in CARE during the transition to telehealth services were recruited for participation. Although the mentalizing-focused approach did not require adaptation for delivery via telehealth (

10), providers received training in how to navigate the adjustment to telehealth service delivery and were provided with HIPAA-compliant videoconferencing (i.e., Zoom) accounts. Sessions were delivered via this platform, and group members were provided with support and assistance in using the technology as needed. During their initial telehealth sessions, several group members had difficulty joining the virtual session or activating the video or audio functions; in such instances, a team member called to facilitate the process. Privacy issues associated with the new format were discussed with group members during the initial telehealth sessions; group leaders requested that group members attend the group from a private space and use headphones to ensure confidentiality.

Caregivers completed Qualtrics surveys before and after participation in their first telehealth group session and 20 weeks after their initiation of telehealth services. At the 20-week follow-up, four participants were no longer enrolled in CARE telehealth treatment because of relocation or a care transition for the child. Of these four, only two could not be reached for follow-up. Quantitative and qualitative measures were used to evaluate psychiatric distress and the preliminary acceptability of the telehealth version of CARE. The study was approved by the institutional review board associated with the clinic’s university hospital system. Participants provided informed consent and received no financial incentive for participation.

Measures

Treatment engagement.

Treatment engagement in the telehealth group therapy was assessed by comparing participants’ no-show, within-session participation, and attendance duration rates in the 3 months before and after the transition to telehealth groups, with lower or nonsignificant differences in these rates indicating comparable treatment engagement for the telehealth adaptation. No-show rates were calculated by using the number of sessions participants missed of the total number of weekly sessions offered during each 3-month period. In-session participation and attendance duration rates were compared among a stratified randomly selected subsample of group session audio recordings across the same time periods. Research assistants reviewed 33% of audio recordings from both time periods (the recordings were stratified by month and by CARE group and were then randomly selected).

Participation was operationalized as participating in the session beyond the initial greetings, either by sharing or by responding to another group member. Participation rates were determined by calculating the percentage of the number of caregivers who contributed to the group discussion relative to the number of all caregivers who attended the session. Duration of attendance was operationalized via categories of full session attendance, arrived late, or departed early. Full session attendance allowed for grace periods of 15 minutes for arrival and 5 minutes for departure.

Psychiatric distress.

Psychiatric distress was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) (

36) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 Scale (GAD-7) (

37). PHQ-9 and GAD-7 data were collected in the week before the participants’ initial telehealth session and at the follow-up 20 weeks after beginning the telehealth therapy.

The PHQ-9 is a widely used, 9-item, self-report measure of depression that has been validated in numerous studies with clinical and general populations (

36,

38,

39). Items ask about recent frequency of experiences, such as “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” and are scored on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptomatology; a total score of 10 is considered a standard cutoff score for clinical depression.

The GAD-7 is a widely used, 7-item, self-report measure of anxiety and worry that has shown adequate validity and reliability in numerous samples (

37,

40,

41). Items focus on recent frequency of being bothered by experiences, such as “not being able to stop or control worrying” or “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge,” and are scored on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety severity and a cutoff score of 10 considered to be in the clinical range.

Treatment acceptability.

Treatment acceptability was explored with the Group Session Rating Scale (GSRS) (

42) following participants’ initial group telehealth session. The GSRS is a 4-item, self-report clinical tool that measures four aspects of alliance: relationship, goals and topics, acceptability of the approach, and sense of overall fit. Responses are rated on a 10-point spectrum. Scores are summed out of a total possible score of 40. The GSRS has been shown to have adequate reliability and concurrent validity (

42).

Privacy concerns.

To explore participants’ concerns and experience related to privacy during the telehealth treatment, two binary (“yes” or “no”) response items were included in the surveys given before and after the initial telehealth session. Before their initial telehealth session, participants were asked, “Do you have any concerns about privacy with the telehealth format?” After their initial telehealth session, participants were asked, “Does the telehealth format affect your experience of privacy?” Participants who endorsed privacy concerns in either survey were asked to elaborate on their specific telehealth-related concerns in a text entry item. These items had a 100% response rate both before and after the initial telehealth session.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were computed by using SPSS Statistics, version 26.0. Because skew and kurtosis of all measures were ±3, indicating that measures were normally distributed, parametric tests were used for the primary statistical analyses. To test for meaningful change between variables, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were computed (where 0.20=small, 0.50=medium, and 0.80=large effect) for all differences by using pooled variance (

43). Changes in participant no-show rates from the 3 months before and after the transition to telehealth were analyzed by using paired samples t tests and effect sizes. Changes in participants’ PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores before their first telehealth session compared with their scores at the 20-week follow-up were analyzed by using paired samples t tests and effect sizes.

We examined the number of group members who achieved reliable changes on both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 by using the reliable change index (

44). On the basis of the previously reported internal reliabilities of the two measures (

36,

37), the standard error change, and the initial standard deviation, the reliable change criterion for the current sample was 5.45 points for the PHQ-9 scores and 4.47 points for the GAD-7 scores. Thus, participants needed to report a reduction of at least 5.45 for the PHQ-9 and 4.47 for the GAD-7 to reflect a reliable change in scores. GSRS (

42) scores were then averaged to determine the level of endorsement of therapeutic alliance and group cohesion after the initial telehealth session.

Results

Participant Demographic Characteristics

Participants in the sample were primarily mothers (83%); all participants were female primary caregivers of a child receiving services in the mental health clinic. The mean±SD age of the children was 11.08±3.42 years. A majority of participants identified as Black or multiracial (75%) and as of Puerto Rican or Caribbean ethnicity. Less than half of participants were married (42%), and a majority were unemployed (67%). Participants’ mean age was 44.17±8.23 years. Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in

Tables 1 and

2.

Treatment Engagement

No-show rates decreased after the transition to telehealth (0.23±0.25) relative to those for in-person treatment (0.32±0.25) prior to the transition. The transition to the telehealth format had a small effect on participant no-show rates, although this decrease did not reach statistical significance. In-session participation rates were 100% during the in-person sessions and remained at 100% during the telehealth sessions. Duration of attendance was 95% across all in-person sessions (i.e., one group member arrived late twice across 12 group sessions) and increased marginally to 97% across all telehealth sessions (i.e., one group member arrived late once across 12 group sessions).

Psychiatric Distress

Depressive symptoms.

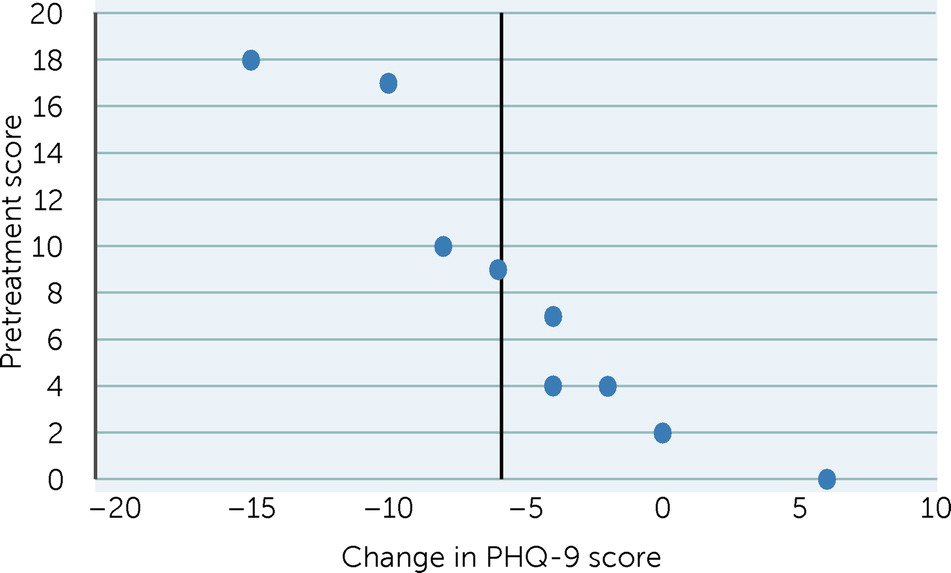

As shown in

Table 3, participants reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms (i.e., lower PHQ-9 scores) at the 20-week follow-up (3.10±2.02) than they did prior to their first CARE telehealth session (7.80±5.96). Participation in CARE telehealth sessions had a large effect on depressive symptoms (d=–0.75), with a statistically significant mean decrease of 4.70 (t=2.61, df=9, p=0.028). Five of the 10 participants who completed the follow-up survey reported a reliable change in depressive symptoms between pretreatment and the 20th week of the telehealth sessions. Specifically, four participants reported an average reliable decrease of 9.75 points, and one participant reported a reliable increase (i.e., deterioration) in depressive symptoms (

Figure 1).

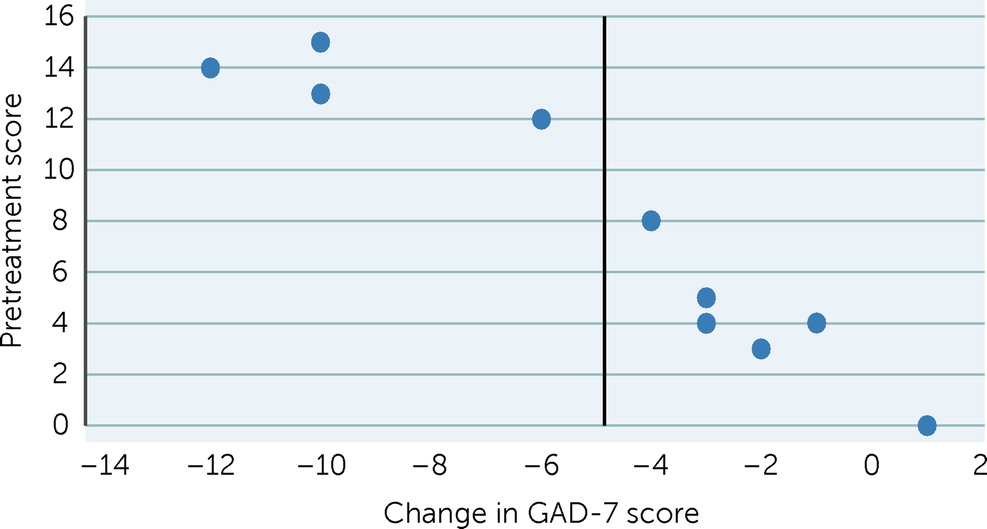

Anxiety symptoms.

Participants reported significantly fewer symptoms of anxiety (i.e., lower GAD-7 scores) at the 20-week follow-up (2.80±1.75) than they did prior to their first telehealth session (8.20±5.47). Participation in CARE telehealth sessions had a large effect on symptoms of anxiety (d=–0.94), with a statistically significant mean decrease of 5.40 (t=3.86, df=9, p=0.004). Four of the 10 follow-up participants experienced a reliable decrease in anxiety symptoms, with an average reliable decrease of 9.5 points at the 20-week follow-up (

Figure 2).

Treatment Acceptability

Treatment acceptability was explored through participant ratings of therapeutic alliance and group cohesion. On average, the participants reported high levels of alliance and cohesion after their first telehealth session, as measured by the GSRS (39.92±0.29). All participants fully endorsed several items on this scale, giving a rating of 10 of 10 with regard to perceived fit of the leader’s and group’s approach; feeling like part of the group; and feeling understood, respected, and accepted by the leader and the group.

Privacy Concerns

Prior to attendance in the first telehealth session, 25% (N=3) of participants reported concerns about privacy. These concerns included being at home with other household members, other group members having household members at home, and technology-related issues such as hacking. After attending their first telehealth sessions, 92% (N=11) of participants indicated that the telehealth format did not affect their experience of privacy, suggesting that the experience in the telehealth session may have alleviated concerns for several participants and did not prompt new concerns for others.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate continued patient engagement in and the acceptability of a mentalizing-focused group parenting program adapted to a telehealth format after the emergence of COVID-19. Our results indicated that the participants found the adapted service delivery format to be acceptable and beneficial, despite the adjustments required by the patients and providers. Rather than showing disengagement after conversion to telehealth, our results suggested a modest, if nonsignificant, reduction in no-show rates compared with in-person group sessions, which is consistent with other findings (

45). This trend underscores the potential value of telehealth technologies, regardless of pandemic-related circumstances, especially within underserved communities where high unmet social needs contribute to health disparities. Recent evidence (

30) illuminating a strong correlation between unmet social needs, such as for transportation, and missed appointments within an urban health system suggests that telehealth may help reduce these disparities. Indeed, several participants commented on the convenience of the telehealth format and expressed their wish that the telehealth option had been available previously. Overall, participant feedback, along with the comparatively improved attendance rates, indicated that the group telehealth format was satisfactory to participants and may have enhanced access to care.

Although telehealth offers promise as an accessible format for care in underserved communities, potential challenges include lack of familiarity with and access to technology and connectivity as well as issues protecting confidentiality and data security (

15). Group leaders provided a practical orientation to the telehealth platform and imparted guidelines related to safe and appropriate clinical videoconferencing practice. Many participants encountered initial technical difficulties yet persevered. The collective experience of isolation as a result of quarantine and social distancing during the pandemic, as well as heightened concerns about effective parenting during an exceptionally stressful time, may have contributed to the motivation and engagement demonstrated by the participants, despite these challenges and a steep learning curve (

29).

The generalizability of these findings may be limited by the small sample size and because all participants had attended at least 12 CARE group sessions before the shift in format and thus may have been a particularly engaged sample. Given that higher levels of cohesiveness have been observed in teletherapy groups with more stable group membership (

46), the preexisting group rapport and connectedness among our participants likely contributed to the successful transition to telehealth sessions as well as to the reported therapeutic alliance and group cohesion. Our cohort also had access to needed devices and the connectivity required for telehealth. Although this access was serendipitous for providing the ability to participate in telehealth groups, it is not typical of many patients who receive care in our clinics (

47). The growing evidence for acceptability and effectiveness of telehealth interventions continues to underscore the importance of building access to relevant technologies within underserved communities (

48).

To expand this pilot study, we have embarked on a larger community-based, quasi-randomized clinical trial of CARE delivered via telehealth. In future work, we plan to evaluate whether telehealth parenting groups have conferred benefits on family functioning during this public health crisis. Early research (

49) indicates that the impact of quarantining on children’s behavioral and emotional problems is mediated by parental stress and stress within the parent-child dyad. Furthermore, symptoms of parental anxiety and depression during the pandemic have been associated with higher potential for child abuse, whereas parental support has been associated with lower perceived stress and decreased risk for child abuse (

50). The prolonged timeline expected for COVID-19 mitigation efforts necessitates consideration of their implications for family mental health. The outcomes such as those reported here suggest that mentalizing-focused group parenting interventions can help alleviate parental psychiatric distress in the context of pandemic-related family stressors.

Conclusions

Although the mentalizing-focused approach may be particularly suited to supporting emotion regulation and fostering connections, the fundamental principles of mentalizing in clinical work are transtheoretical, and the provision of various forms of group-based telehealth services are poised to offer caregivers acceptable and effective mental health care that encourages social connection despite ongoing pandemic-related obstacles. Our pilot study supports the acceptability of group teletherapy as a means for providing mental health services and a much-needed sense of community and normalization during a time of unprecedented community and global crisis.