The advent of second-generation antipsychotic drugs has been hailed as a breakthrough in the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. As a class, these drugs are believed to be more effective and safer than conventional antipsychotics (

1–

9). Claims of their superior efficacy have been based, in large part, on studies of clozapine, which has demonstrated its superior efficacy in patients that were either predominantly refractory or only partially responsive to conventional antipsychotics (

2–

6,

9). Other second-generation antipsychotic medications introduced subsequent to clozapine such as risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are also widely believed to have superior efficacy to conventional antipsychotic drugs, although the evidentiary basis for this is variable. Understandably, these medications, along with clozapine, have been preferentially used in patients whose symptoms are either predominantly refractory or only partially responsive to conventional medications (i.e., treatment-resistant patients). Because these other drugs do not have the same risk of agranulocytosis as clozapine, they are used as “screening” medications for clozapine in treatment algorithms and practice patterns (

10).

It is important to know definitively and precisely the comparative efficacy of the new medications vis-à-vis the previous standards. Among other reasons is the fact that the new medications are much more costly. Moreover, to switch a patient who may be persistently symptomatic but stable to a new atypical drug with the promise of an improved response is not without the risk of destabilization and all of the attendant consequences. In addition, there is the potential loss of credibility with our patients and public policy makers. The introduction of the phenothiazines and other classes of neuroleptics in the period between 1953 and 1980 both raised expectations that were never fully realized and prompted policies of deinstitutionalization that were not very successful and have had considerable adverse social ramifications.

Discussion

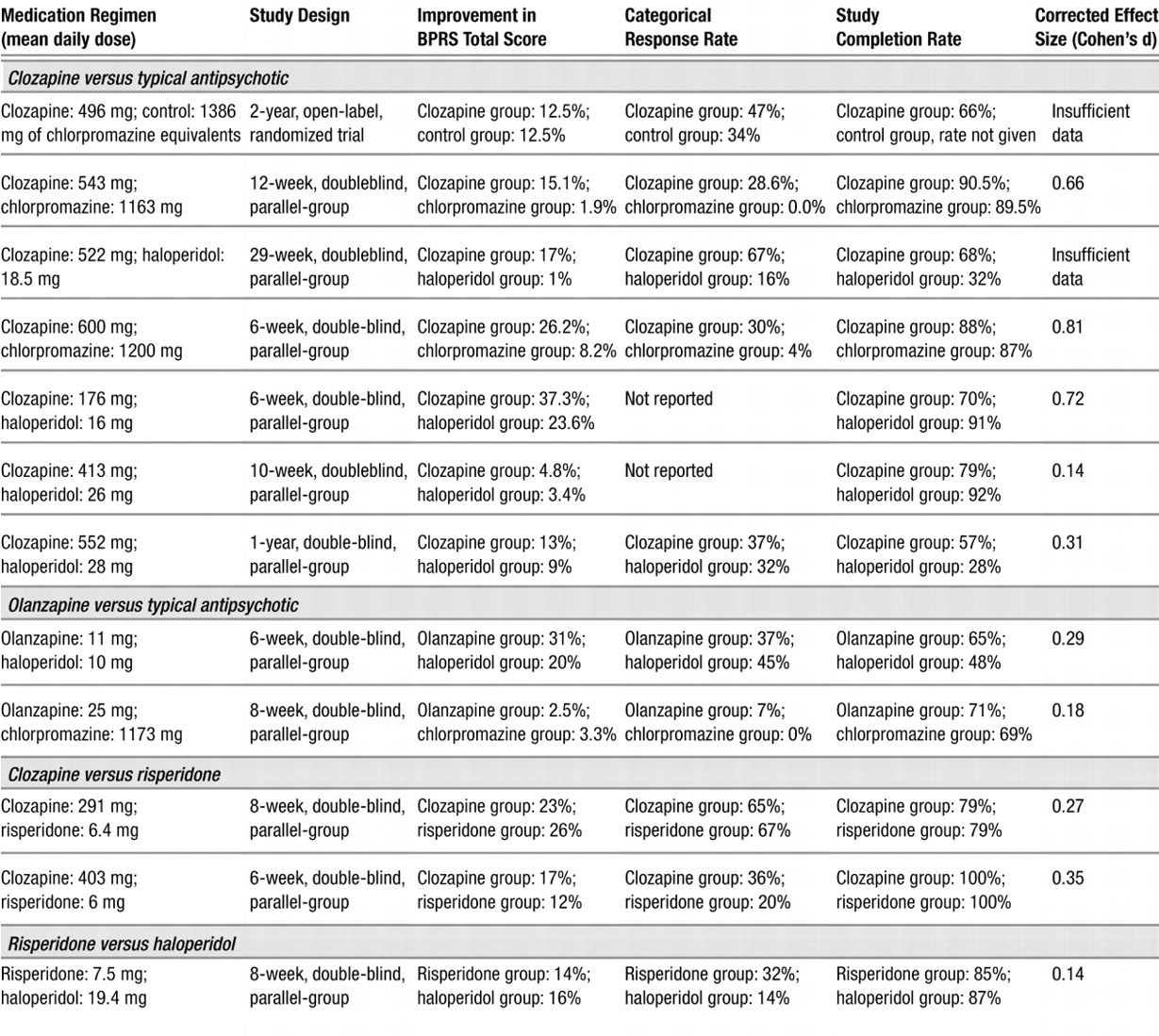

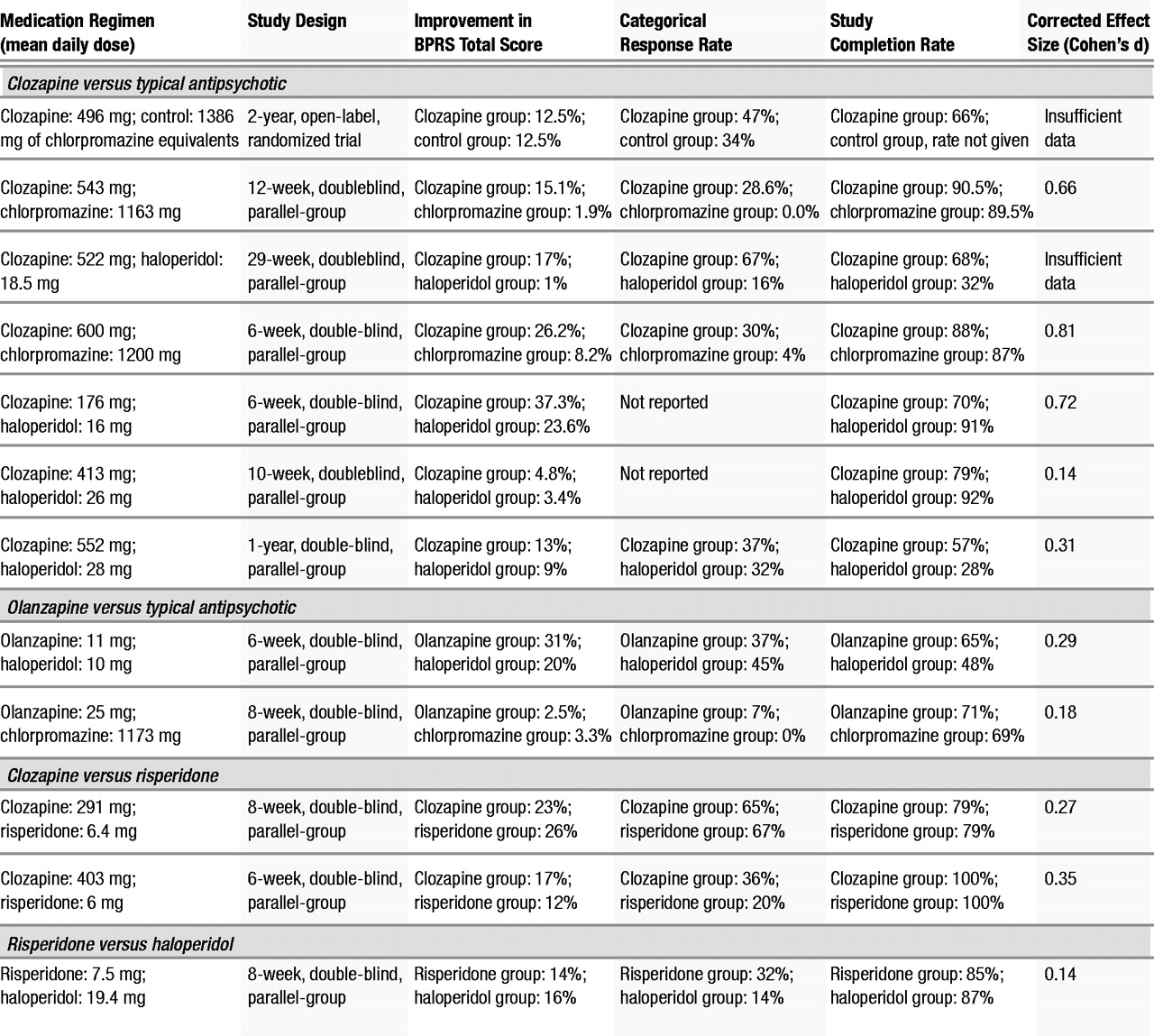

In the aggregate, the results indicate that the second-generation antipsychotics as a class, to the extent that they have been studied in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, exhibit superiority in measures of treatment compliance and reduction of extrapyramidal symptoms compared to typical antipsychotics. However, the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics, other than clozapine, in the reduction of symptoms in treatment-resistant schizophrenia is not established. This is principally because there are relatively little data with which to evaluate this question for second-generation antipsychotics apart from clozapine. Using an ANCOVA model with baseline score as a covariate, we found that the clozapine treatment group had a greater reduction in BPRS total score than the typical antipsychotic treatment group. The association of greater reductions from baseline in BPRS total score in the clozapine treatment group did not reach statistical significance in the weighted least squares analysis model. One possible reason for this discrepant result was that the ANCOVA model used the endpoint as the dependent variable with the initial time point as a covariate, whereas the weighted least squares model used the change score as the dependent variable. Another possible reason for the discrepancy is that the two models weighted the studies differently. As we noted, the ANCOVA model weighted each study equally, which, in effect, gave greater weight to small studies that showed large effects. This might give a small study with a large effect size greater influence than would the weighted least squares model. The weighted least squares analysis, by weighting studies proportionally to their sample size, in effect gave greater weight to larger studies that did not show differences between the treatment groups. Finally, the discrepancy may be the result of using estimated variance. Typically, a weighted least squares analysis weights by a function of the sample size and the variance; however, the actual variance data were not available for all of the studies included in this analysis so estimated variance was used.

In any case, the difference between the ANCOVA model and the weighted least squares model with regard to BPRS total score was minimal and should not affect the interpretation of the results. In both analyses, the direction of the effect was the same (BPRS total score for the clozapine treatment group was lower than for the typical antipsychotic treatment group). This provides evidence that clozapine is effective in reducing overall psychopathology in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia compared to typical antipsychotics. However, it is important to note that the effect size of the clozapine treatment effect varied considerably across individual studies, although the combined effect size was moderate.

The significant interaction between baseline psychopathology and treatment in the ANCOVA meta-analytic comparison of clozapine-treated patients to patients treated with a typical antipsychotic suggests that treatment-resistant patients who are more severely symptomatic at baseline are most likely to benefit from treatment with clozapine. Since baseline psychopathology was controlled for as a covariate in the ANCOVA, this appears to be a real effect and not an artifact or a result of regression toward the mean.

Individual categorical analyses performed to evaluate the efficacy of both clozapine and olanzapine suggested that both of these treatments were superior to typical antipsychotic medications in producing clinically significant improvement. However, the analysis comparing olanzapine to typical antipsychotics was based on only two studies (

1,

15), which found contrary results. Conley et al. (

15) found no advantage of olanzapine compared to chlorpromazine in very ill, chronically institutionalized schizophrenic patients, whereas Breier and Hamilton (

1) found an advantage of olanzapine compared to haloperidol in a group of treatment-resistant schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients, 50% of whom were outpatients at the time of study entry. One reason for the contradictory findings of these two studies may be that they involved different patient groups, although both were ostensibly refractory. The Conley et al. study was conducted in the United States, and its patients had a baseline total BPRS score of 57, whereas the Breier and Hamilton study was done in Europe with patients who had a mean baseline BPRS score of 37.5. These two studies suggest that, unlike clozapine, olanzapine (at least at the doses used in these studies) may be effective in treatment-resistant subjects who are less severely ill but not as effective in the sickest treatment-resistant subjects.

The two studies that compared risperidone to clozapine found no difference in the efficacy of these two second-generation antipsychotic medications in the treatmentresistant population that they studied (

12,

13). From these studies, and our evidence that clozapine is more effective in resistant patients than are typical antipsychotics (

3–

6,

9), we could infer that risperidone is more effective than typical antipsychotics by extrapolation of its noninferior efficacy to clozapine. However, characteristics of sample selection may have contributed to the inability to detect a differential effect of clozapine and risperidone in the treatment of the subjects in these studies. The subjects of Breier et al. (

13) were outpatients with relatively low baseline psychopathology (mean baseline BPRS score was 38) and were considered partially responsive with residual symptoms. Bondolfi et al. (

12) did not prospectively treat subjects with a typical neuroleptic to screen out treatment responders and included subjects who were treatment-intolerant as well as treatment-resistant, without reporting the proportion of each of these groups in the sample. The Wirshing et al. study (

17) found no difference in the treatment efficacy of risperidone compared to haloperidol in patients with high levels of baseline psychopathology. These studies, although clearly not definitive, do not provide convincing evidence to support the hypothesis that the sickest treatment-resistant patients would do as well with risperidone as they did with clozapine.

The ANCOVA models did not reveal differential efficacy of clozapine compared to typical antipsychotics in the treatment of negative symptoms. This may be in part due to a lack of power in the analysis, since only four studies contributed observations to this analysis. When examining the effects of clozapine or olanzapine on negative symptoms in individual studies, a reduction of negative symptoms is not definitive. Kane et al. (

5), Kumra et al. (

6), and Breier et al. (

13) found that second-generation antipsychotics reduced negative symptoms, whereas Buchanan et al. (

14), Conley et al. (

15), and Kane et al. (

4) did not. Since the Kane et al. sample (

5) had high baseline extrapyramidal symptoms, the observed improvements in negative symptoms in the clozapine-treated group in that study could be secondary to continued reduction of extrapyramidal symptoms throughout the duration of the trial. This interpretation is supported by studies that have found an association between improvement of negative symptoms and extrapyramidal symptoms (

8). In contrast, Kumra et al. (

6) found clozapine effective in treating negative symptoms in adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia who began clozapine treatment at an average age of 14.4 years (SD=2.95). Since these patients had a low level of extrapyramidal symptoms at baseline, the reduction in negative symptoms might be due to a reduction in primary negative symptoms. This suggests that early intervention with clozapine in young refractory patients may result in enhanced efficacy of clozapine in the reduction of negative symptoms. The differential effects of olanzapine on negative symptoms as reported by Breier and Hamilton (

1) and Conley et al. (

15) may be due to the fact that Conley et al. studied a sicker population of patients who had been chronically institutionalized in state or VA hospital systems and had a mean baseline BPRS score of 57, compared to a mean baseline BPRS score of 38 reported in the Breier and Hamilton study. However, additional studies are needed to clarify the basis for this difference.

Some of the most troublesome side effects associated with typical antipsychotic drugs are extrapyramidal symptoms, including acute dystonic reactions, drug-induced parkinsonism, and akathisia. Extrapyramidal symptoms occur in up to 75% of patients treated with typical antipsychotics and significantly contribute to medication noncompliance (

26–

28). Another troublesome adverse consequence of long-term treatment with typical antipsychotics is tardive dyskinesia (

29,

30). The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia is believed to increase with total cumulative drug exposure. This risk, on average, is about 5% per treatment year for the first 5 to 7 years (

29–

31).

Despite the limited number of studies that contributed to these analyses, advantages of clozapine and olanzapine treatment compared to typical antipsychotic medications in reducing extrapyramidal symptoms were seen. Wirshing et al. (

17) did not find a difference in reduction of drug-induced parkinsonism in the risperidone-treated group compared to the haloperidol-treated group, although patients treated with risperidone received less concomitant anticholinergic medication.

Even though the reductions in total AIMS scores in patients treated with olanzapine and clozapine ranged on average from 30% to 40% (Table 2), the analyses did not demonstrate a greater reduction in AIMS scores compared to patients treated with typical antipsychotics. This failure to demonstrate superior efficacy of second-generation antipsychotic medication in the amelioration of tardive dyskinesia may be due to the small sample size (only four studies contributed data), which may have resulted in inadequate power to detect a difference between groups. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine the effects of these medications on tardive dyskinesia in this population.

Despite the important advantages conferred by the second-generation antipsychotics with regard to motor side effects, concern about other side effects may affect ultimate treatment choice. Second-generation antipsychotics have been associated with weight gain and obesity, which increases the risk for diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease (

32). Among antipsychotics, clozapine and olanzapine appear to cause the most weight gain, with risperidone causing a lesser amount of weight gain and haloperidol the least (although haloperidol may not be representative of all typical antipsychotics in this respect) (

33). Given this effect, it is not unreasonable to consider that when treating obese patients with underlying medical problems such as diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia, there may be advantages conferred by treatment with the second-generation antipsychotics ziprasidone, aripripazole, iloperidone (each currently awaiting approval from the Food and Drug Administration) or typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol, since these are less likely to result in significant weight gain and exacerbate underlying medical problems. Despite the significant medical consequences of drug-induced obesity, neither of the two studies that used olanzapine as a treatment condition (

1,

15) reported on weight changes, and only three of the studies that used clozapine as a treatment condition (

3,

6,

13) reported on weight changes.

An additional troublesome side effect of antipsychotic medications is hyperprolactinemia, which is induced by the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist properties of typical antipsychotic drugs and risperidone. The resultant hyperprolactinemia can lead to impotence, galactorrhea, amenorrhea, and a higher risk of osteoporosis in psychiatric patients (

34). These associated sexual and reproductive side effects may affect the ultimate choice of treatment for a given patient. However, none of the 12 studies reviewed reported on these side effects. Similarly, differences in effects of antipsychotic medications on memory and concentration may affect treatment choice and need to be further studied (

35).

An important measure of outcome is compliance with treatment. A substantial proportion of patients with schizophrenia continue to relapse frequently, often as a result of nonadherence to treatment (

36–

38). Our analyses demonstrated a superiority of second-generation over typical antipsychotics with regard to completion rates, which implies that patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia given these drugs are more likely to comply with treatment.

Finally, the variable and, in many cases, limited effect sizes found in the analyses of comparative drug studies indicate that although there may be some measure of superior efficacy (as well as considerable advantages in safety in terms of neurologic side effects) for the second-generation antipsychotics, they clearly have substantial limitations in their efficacy. The majority of patients improved minimally to moderately, and although they may have been less symptomatic, they still had substantial residual symptoms. Thus, there is a critical need for additional drug development and research on new treatment strategies such as the use of adjunctive treatments with antipsychotic drugs.