Antipsychotic prescription guidelines do not differentiate between male and female patients, yet human studies have shown that the pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of drugs differ between the two sexes (

1–

4). Women’s bodies, on average, contain 25% more adipose tissue than those of men, and most antipsychotic drugs are lipophilic—i.e., accumulate in lipid stores (

5). To minimize the resulting side effects, should there be longer intervals between doses in women than men? Women undergo menstrual cycles, and many take contraceptive pills during adulthood. What is known about interactions between hormones and antipsychotics? Should dose regimens in women be altered during menstrual cycles, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and menopause (

3,

4,

6–

9)? Women in treatment for schizophrenia, more so than men, take a variety of adjunct drugs in addition to antipsychotics. In other words, there are more opportunities for drug interaction, culminating in the possibility of lowered or raised antipsychotic serum levels. Combined with lifestyle factors such as smoking, coffee drinking, or alcohol intake, subsequent divergence from optimum levels of the drug in the brain can be significant (

10,

11). Pregnancy and breast-feeding require an understanding of pharmacokinetics in the pregnant woman, the fetus, and the neonate as well as knowledge about developmental risks, the impact of drugs on labor and delivery, the potential for withdrawal reactions in the infant, behavioral toxicity, and drug concentrations in breast milk (

12–

22).

Antipsychotic drugs are frequently prescribed for untoward behavior (e.g., aggressive behavior) as much as for psychotic symptoms (

23). Reported higher prescribed doses in men may be due to this and not to response factors. Rates of side effects to most drugs are reported to be higher in women than in men (

24). Is this true for antipsychotic drugs? Does it imply that women are systematically overdosed, since most side effects are dose related? Neurotransmitter numbers diminish with age at different rates in women and men (

25). Should aging men and women be prescribed different drug regimens (

26)? When clinicians write a prescription for a patient with schizophrenia, should it matter whether the person in front of them is a man or a woman?

Before discussing antipsychotic drug issues, it is important to first understand gender differences in schizophrenia and how they can affect medication needs at different stages of illness.

Making the diagnosis in women and men

The diagnosis of schizophrenia is usually made between ages 15 and 25. During those 10 years, schizophrenia is diagnosed in 12 men to every 10 women (

32). This may be because the onset of schizophrenia is delayed in women. Many reasons for such a possibility have been considered: greater vulnerability of the male brain because of slower maturation (

33), greater exposure to birth injury in males (

34), a neuroprotective effect of female hormones (

35), less lateralization of the female brain (

36), and greater exposure of males to head trauma (

37). It may be that men come to medical attention earlier than women because of the nature of their behavior when they are psychotic, or it may be that women with schizophrenia are initially misdiagnosed. Narrow diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia exclude those whose initial episode is brief and affect laden (

32), and these individuals are mainly women (

38).

Earlier onset of schizophrenia (i.e., in men) usually means a more severe course of illness (

39). On the other hand, a delayed diagnosis (i.e., in women) is a potential problem for treatment because long-lasting symptoms have been shown in prospective studies to be relatively nonresponsive to antipsychotic drugs (

40,

41). A schizophrenic illness initially diagnosed as depression or a bipolar disorder (i.e., in women) means that antidepressants and mood stabilizers have preceded treatment with antipsychotics. Such prior treatment can “prime” neural networks and result in an unanticipated antipsychotic response later (

42).

Between ages 25 and 35, equal numbers of men and women are diagnosed with schizophrenia (

32). After age 35, a first visit to the psychiatrist is 50% more frequent in women with schizophrenia (

32). Very late onset of schizophrenia is also much more common in women than in men (

43). In other words, first-episode samples are composed of younger men and older women. It is, therefore, important to control for age when comparing results of drug response in women and men in first-episode studies.

Course of schizophrenia in women and men

Despite the possibility that their illness comes to treatment late, women with schizophrenia experience less severe symptoms, fewer hospitalizations, shorter admissions, more posthospitalization employment, less trouble with the law, and more intimate relationships than men with schizophrenia (

30,

31). This has led to the conjecture that the response to antipsychotic drug treatment is more robust in women than in men (

44). Superior outcome may have little to do with response to treatment and more with treatment adherence, life style, social supports, the advantage of later onset, and relative hormonal protection (

45,

46). The corollary is that if women are doing better, their maintenance antipsychotic doses need not be as high as those of men.

Schizophrenia mortality from unnatural factors (suicide, accident, homicide) is significantly higher in men than in women (

47). As proportionately more seriously ill men in the schizophrenia population die, the levels of acuity between the two sexes begin to approximate, and indeed, in older age, the severity of illness is similar between the two sexes. This is true not only with respect to hospitalization variables such as the number and frequency of admissions and the lengths of stay but also with respect to mental status at follow-up, social adaptation, and occupational status. In older age, there may be less need for gender-specific prescribing (

26,

48).

Antipsychotic treatment response and serum levels in men and women

Genetics, age, height, weight, lean-fat ratio, diet, exercise, concurrent disease, smoking and alcohol, and the administration of concomitant drugs all contribute to antipsychotic drug response, as does end-organ sensitivity. Together, these factors can account for a 10-fold variability in the dose needed for effective response. Men and women show differences in all of these variables, either as a result of the action of sex-specific hormones or of divergent gender roles. So the stage is set for a somewhat different response to medication in the two sexes.

In a prospective drug-naive population, antipsychotic response was shown to be superior in women (

49), and in a chronically ill population, men were found to require twice as high a dose as women for effective maintenance (

50). But studies comparing response in men and women are few. As a group, women have higher antipsychotic plasma levels than men after receiving the same dose of drug (

51). Male sex was associated with nonresponse at 1 year in a first-episode sample (

52) but not with likelihood of relapse after response (

53). In the most methodologically rigorous study, with age of onset, course of illness, prior hospitalizations, and premorbid functioning controlled, no gender-specific difference was found in neuroleptic dose or dose by weight (

54).

It has been postulated that hormonal fluctuations within phases of the menstrual cycle may influence pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs. Menstrual cycle variations do occur in renal, cardiovascular, hematological, and immune systems (

4) and could theoretically also affect protein binding and the volume of distribution of a particular compound. When age and menstrual status (but not menstrual phase) were controlled, one study found no dose-by-sex difference (

55). One group found no effect of menstrual cycle on cytochrome enzymes 2D6, 3A, or 1A2, suggesting that antipsychotic levels should be impervious to menstrual phase (

56–

58). Smoking status, as we will see, has strong effects on the metabolism of certain drugs, and one research team has speculated that such antipsychotic dose differences as have been found between men and women are due to more men smoking and smoking more heavily than women (

59).

Goff et al. (

60) compared prescribed antipsychotic dose in smokers and nonsmokers. Current smokers received a mean dose of 1160 mg/day in chlorpromazine equivalents, while nonsmokers were given 542 mg/day in chlorpromazine equivalents. Overall, multivariate analysis of covariance demonstrated a significant main effect for smoking status but not gender or the interaction between gender and smoking.

After an oral dose, plasma concentrations of haloperidol (metabolized by means of CYP2D6) are significantly lower in smokers than in nonsmokers (

61,

62). Smoking may induce CYP2D6, but the story is probably more complicated. A recent study found no significant difference in the haloperidol concentration-to-dose ratio between nonsmokers and smokers. In patients with a non-2D6*10 homozygous genotype, smokers had a significantly lower haloperidol concentration-to-dose ratio than nonsmokers, but this was not the case for smokers with a 2D6*10 homozygous genotype (

63). This suggests that the effect of smoking on the concentration-to-dose ratios of drugs depends on a person’s genotype (

64). Kelly et al. (

65), in a fixed-dose study, found that women had higher plasma concentrations of olanzapine than men. But the greater prevalence of smoking in men could have been responsible for these findings, since tobacco is an inducer of CYP1A2, the main metabolizing enzyme for olanzapine (

66,

67). Taking smoking and other factors into account, however, the consensus for olanzapine is that there continues to be a tendency for higher concentrations in women. Being a woman, shown through recent therapeutic drug models, accounted for 27% of observed interindividual variability (

68,

69). The enzyme CYP1A2 appears to be less active in women than in men, leading to relatively higher blood concentrations in women, not only of olanzapine (

65,

69) but also of clozapine (

70). A recent study of patient-related variables on clozapine concentrations found non-significantly higher median steady-state plasma concentrations in women than in men and higher concentrations in nonsmokers than in smokers (

71). Neither gender nor age apparently has a significant effect on plasma levels of ziprasidone, which is metabolized by CYP3A4 (

72).

Drug interactions

Women are more likely than men to be taking antidepressants, mood stabilizers, analgesics, and contraceptives or hormone replacements, and these agents can interact with antipsychotics, especially those processed mainly by the CYP2D6 enzyme subsystem. In a retrospective analysis of 168 patients taking haloperidol, those treated with concomitant antiepileptic drugs showed a mean ratio of steady state to dose that was 27% lower than those not taking antiepileptic drugs (

73). Carbamazepine reduced the median concentration-to-dose ratio of olanzapine (primarily metabolized by means of CYP1A2 with contributions from CYP2D6) by 38% (

66,

74) but did not clinically affect the level of ziprasidone (CYP3A4) (

75). Patients treated with antiparkinsonian drugs showed a 25% higher mean concentration-to-dose ratio of haloperidol than those not taking antiparkinsonian drugs (

73). Neither menopause nor estrogen replacement therapy altered intestinal or hepatic CYP3A activity (which is mainly responsible for the metabolism of ziprasidone and quetiapine) relative to a comparison group of young women (

76), nor did the administration of a contraceptive pill (

77). Ziprasidone, co-administered with ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, did not lead to a loss of contraceptive efficacy nor increase the risk of adverse events (

78).

Long-term administration of St. John’s wort, however, resulted in a significant and selective induction of CYP3A activity in the intestinal wall—i.e., it potentially reduced the efficacy of ziprasidone and quetiapine (

79). Selective serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine) were significantly associated with 4.6-fold higher concentrations of risperidone. Significantly higher concentrations (29%) of the active metabolite (by means of CYP2D6) 9-hydroxy-risperidone were also observed in patients with biperiden co-medication (

80). The SSRI fluvoxamine is a potent inhibitor of CYP1A2 (

81). The level of drugs metabolized through this route can be increased 400–1,000-fold if fluvoxamine is co-administered. Oral contraceptives also inhibit this enzyme.

When determining effective doses of antipsychotics, smoking status and adjunct medication (including herbal products) are important pieces of information. Blood levels should be taken when patients are concomitantly taking SSRIs, carbamazepine, or antiparkinsonian drugs, and women must be asked about contraceptive medication (

82) and hormone replacement.

Treatment side effects

The incidence and severity of antipsychotic side effects are heavily dependent on a serum level that, in turn, depends on prescribed dose, treatment adherence, metabolism, and volume of distribution. Acute dystonia, long thought to be more prevalent among men, has been shown, in a first-episode, fixed-dose, 10-week study, to occur, at equivalent doses, more often in women (

86). Earlier clinical studies had not taken into account the fact that young male patients were commonly given higher doses than women. Tardive dyskinesia, still frequently cited as most common in elderly women, has been shown by a cohort (as distinct from a cross-sectional) study to be more of a risk factor for elderly men (

87), although its severity may be relatively greater in women in their later years (

88).

A statistical analysis of sex differences in all adverse drug events has shown that, although equal numbers of such events were reported for men and women, those reported for women were more serious (

24). An example for antipsychotics is the rare side effect of pulmonary embolism, a problem with drugs with an affinity for the serotonin 5-HT

2A receptor. This complication appears to be more common in women (

89).

A better-studied example of a significant sex difference in the toxicity of antipsychotics is the drug-induced cardiac arrhythmia known as torsade de pointes, which is secondary to a prolonged QT interval (

24). Women have longer QT intervals than men on average, but the QT interval is mainly genotype dependent (

90). Emergency use of high-dose intravenous drugs that prolong the QT interval, such as haloperidol, may be especially dangerous in women (

91).

Severity aside, side effects of antipsychotic medications may hold different significance for men and women. On the whole, men are most disturbed by the effects that interfere with performance, especially sexual performance; women are more distressed by effects that detract from their appearance (

92). Obesity is particularly stigmatizing for women, and antipsychotic-induced increases in body mass index are more prevalent in women than in men (

93,

94). The future health effects/risks of antipsychotic-induced obesity (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and hyperlipidemia) are serious for men

and women (

95–

98), and women may be more at risk for some of these complications (

99). Obesity also has specific adverse effects on labor and delivery in women (

100) and on the incidence of neural tube defects in their infants (

101).

The results of several trials confirm that women are more susceptible to drug-induced hyperprolactinemia than men (

102,

103). A recent review of the literature indicates that prolactin concentrations can rise to 10 times normal levels during antipsychotic treatment, and as a consequence, in some studies, up to 78% of female patients have been reported to suffer from amenorrhea with or without galactorrhea (

104). Studies in women with hyperprolactinemia resulting from pituitary tumors have demonstrated high rates of osteoporosis believed to result from secondary hypoestrogenism. Women taking drugs that raise prolactin levels show decreased bone mineral density relative to women treated with drugs less prone to increase prolactin (

105,

106). Individuals with schizophrenia are at increased risk for osteoporosis and bone fractures, not only from low estrogen levels but also from poor diet, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, and polydipsia. Some antipsychotic medications may further increase the risk of fractures by causing dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, and falls (

107). Anticholinergic effects also increase the risk of falling (

108).

A question has also been raised about the connection between prolactin elevation and breast cancer (

109,

110), but studies that have found increased rates of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia have not controlled for two potent breast cancer risks: age at first giving birth and parity status. The younger a woman is at the time of her first pregnancy and the more children she has, the less likely she is to develop breast cancer. When this is taken into account, the risk of breast cancer is not increased in women with schizophrenia treated with dopamine antagonists (

111).

All antipsychotics have the potential to interfere with sexual function in both men and women (

112–

114). This is a complex effect and is not directly related to hyperprolactinemia (

115).

Some side effects, such as sedation and orthostatic hypotension, are equally prevalent in the two sexes and may interfere with optimal functioning. In women with parenting responsibilities, however, these relatively benign side effects can have serious consequences—e.g., loss of child custody (

116).

Most side effects are dose related, and side effects in women may indicate that they are being over-medicated. Alternatively, women may show particular sensitivity to certain side effects (and men to others). The consequence of side effects may be gender specific.

Pregnancy

Guidelines for prescribing antipsychotics during pregnancy and lactation include the following (

12–

22,

117–

123):

2.

Avoid drugs if possible during weeks 6–10

3.

Use antipsychotics about which most is known during pregnancy

4.

Keep doses low before delivery

6.

Have patient take medications just before infant’s longest sleep of the day

7.

Consult with pediatrician

Optimal prescription of antipsychotics during pregnancy is complicated by altered pharmacokinetics across the three trimesters, fear of teratogenesis, need to safeguard the smooth progress of labor and delivery, need to prevent withdrawal effects in the neonate, and concerns about subtle effects on the infant’s neurodevelopment. The latter concerns are also present during breast-feeding. Plasma volume increases by about 50% during pregnancy and body fat also increases, expanding the volume of drug distribution. Blood flow to the kidneys rises, as does the glomerular filtration rate, thus speeding renal elimination. Many liver enzymes are activated during pregnancy, so drugs are metabolized more quickly, consequently increasing the rate of clearance. The end result is that plasma drug concentration is lowered during pregnancy. At the same time, because of increasing titers of sex steroids acting on neurotransmitter receptors, some pregnant women may not require high drug concentrations in order to stay symptom-free. Changes in physiology begin in early gestation and are most pronounced in the third trimester of pregnancy. Further changes occur during labor, with some returning to baseline within 24 hours of delivery, while others remain for up to 12 weeks postpartum (

15,

17,

22). There are relatively few specific data on pharmacokinetics/dynamics in pregnancy, so therapeutic guidelines must be based on observational studies and basic principles.

The use of medications during pregnancy and lactation requires critical attention to the timing of exposure, the dose and duration of use, and fetal susceptibility. Essentially all psychotropic drugs pass through the placenta. The aim of management of women with schizophrenia during pregnancy and the postpartum period is to achieve an optimal balance between minimizing fetal and neonatal exposure to drugs and the deleterious consequences of a psychotic mother. Usually monotherapy with the lowest effective dose of a drug for the shortest period necessary is the best strategy. If possible, drug exposure during the first trimester is best avoided (

19). The use of low-potency phenothiazines during the first trimester probably increases the risk of congenital abnormalities by an additional four cases per 1,000 (

124).

A recent study of over 2,000 births to mothers diagnosed with schizophrenia compared to over a million births to women without schizophrenia (

125) found significantly increased risks for stillbirth, infant death, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and small size for gestational age among t he offspring of women with schizophrenia. Women with an episode of schizophrenia during pregnancy had the highest risks. Control for a higher incidence of smoking during pregnancy among the subjects as well as for single motherhood, maternal age, parity, maternal education and country of birth, and pregnancy-induced hypertensive diseases in a multiple regression model reduced the risk. But even after adjustments, there was a doubled risk for women with an episode of schizophrenia during pregnancy in relation to women in the comparison group. The risks for preterm delivery and low birth weight were significantly elevated for all subjects (

125). It is impossible to tell from this study how much of the poorer outcome can be attributed to antipsychotic treatment.

Another study of over 2,000 children of women with schizophrenia found that these infants had an increased risk of postneonatal death largely explained by an increase in sudden infant death syndrome. They also had a marginally statistically significant increase in the risk of congenital malformations (

126). The same study found that women with schizophrenia had fewer antenatal care visits than pregnant women in the general population and that their babies tended to have lower Apgar scores. Subjects were at increased risk of interventions such as cesarean section, assisted vaginal delivery, amniotomy, and pharmacological stimulation of labor (

127). The authors concluded that their findings must be interpreted against a backdrop of presumed differences in socioeconomic status, substance abuse, smoking, and medication use between subjects with schizophrenia and comparison subjects.

Fetal circulation, compared with maternal circulation, contains less protein, leaving more of the drug unbound—i.e., facilitating entry into the brain. Liver enzymes are relatively inactive in the fetus, increasing the possibility of toxic effects. Excretion is relatively prolonged. In addition, the blood-brain barrier is incomplete, and the nervous system is immature and, therefore, it is more sensitive to drug effects (

128). Teratogenic effects are both dose and time dependent, with organs at the greatest risk during their period of fastest development. Week 6 to week 10 is the most vulnerable period. Besides organ malformation, potential risks to the fetus are spontaneous abortion, growth retardation, and immediate neonatal effects, such as extrapyramidal and withdrawal symptoms. Neurodevelopmental effects of antipsychotic drugs have never been demonstrated in humans but remain a theoretical concern (

129).

Not much is yet known about the newer drugs. Clozapine poses special potential risks for the fetus: seizure and agranulocytosis. Thus far, olanzapine appears relatively safe. Twenty-three prospectively and 11 retrospectively ascertained pregnancy reports on pregnant women treated with olanzapine were collected in the Lilly Worldwide Pharmacovigilance Safety Database. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 13%, stillbirth in 5%, and prematurity in 5%—all within the range of normal historic control rates. There were no major malformations (

117).

Most experts suggest minimal use—no use, if possible—of antipsychotics during weeks 6–10 of gestation to prevent teratogenesis and low doses before expected delivery to prevent toxicity and withdrawal in the infant, with immediate resumption of a full dose after delivery because of the high risk of the mother’s decompensation postpartum (

12,

13,

16,

20).

Lactation

A drug that is safe for use during pregnancy may not be safe for the nursing infant. Exposure to antipsychotic medication in breast milk markedly differs from exposure to antipsychotics by the fetus during pregnancy (

118). The non-protein-bound (free) drug in the blood of the nursing mother enters breast milk at a rate that depends on its lipid solubility. The more fat-soluble the drug, the more of it enters. How much antipsychotic drug is present in breast milk at any one time depends mainly on the lipid concentration of the breast milk, which is different in foremilk and hindmilk and changes over time. An important factor is the temporal relationship between maternal drug ingestion and the time of nursing. The neonate’s metabolic and excretory functions mature over time but are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Immature liver enzymes cannot detoxify drugs efficiently nor can the immature kidney competently eliminate drugs. Metabolic pathways in existence at these early stages of development are not always the same ones that exist later, so the metabolites of a drug in the neonate may differ from those in the adult. Relatively low protein binding in the infant increases the serum concentration of free drug that crosses into the brain, and all tissue concentrations are relatively high because of the small volume of distribution (

118).

The literature suggests that infant serum concentrations of antipsychotics are largely unpredictable. Clinical risk assessment is compromised by sparse data, as studies in breast-feeding women and their infants are ethically difficult to conduct. A literature review (

119) concluded that women who are vulnerable to postpartum exacerbation of psychiatric disorders are placed in a difficult position, often choosing to abandon the drugs they need to keep well or going to the other extreme and foregoing breast-feeding with all its known benefits to the infant and to the mother-child bond. These authors advise that parents be provided with all known available information and that the psychiatrist involve the pediatrician in monitoring the infant’s exposure. Della-Giustina and Chow (

120) offer the following advice to physicians advising nursing mothers:

1.

Determine if medication is necessary.

2.

Choose the safest drug available, that is, one that has been proven safe when administered directly to infants, has a low milk-to-plasma ratio, has a short half-life, has a high molecular weight, has high protein binding in maternal serum, is ionized in maternal plasma, and is relatively nonlipophilic.

3.

Consult with the infant’s pediatrician.

4.

Advise the mother to take her medication just after she has breast-fed the infant or just before the infant’s longest sleep period.

5.

If there is a possibility that a drug may put the health of the infant at risk, monitor infant serum drug levels.

The rule of thumb is that, for any drug in breast milk, infants should be exposed to less than 10% of the dose per weight that would be prescribed to them directly. In one study of olanzapine (

121), seven breast-fed infants were exposed to a calculated olanzapine dose of approximately 1%. The olanzapine was below the detection limit in the infant plasma, and there were no adverse effects. The authors of another olanzapine study (

122) (N=9) came to the same conclusion. Premature infants are at relatively higher risk; the possibility of toxicity is reduced as the infant grows. Novel agents, the safety for which there are few data, are better avoided, and clozapine is a problem because of the frequent blood monitoring it requires. Multiple medications are best avoided (

123), as are smoking, alcohol, and over-the-counter medications.

Recommendations

Gender needs to be taken into account when prescribing. Inquiries into symptom fluctuation over the menstrual phase and into diet, smoking habits, substance use, contraceptive pills, over-the-counter and herbal preparations, and prescribed medications are essential. The body’s lean-fat ratio is important to consider, as most antipsychotics are lipophilic. Familiarity with metabolic pathways, metabolites, and interactions of all prescribed drugs is important. Dose-response predictions will vary from person to person (

130). Menopausal status, age, and renal functioning are crucial information. Inquiries need to be made into the effects of hypotension, passivity, sedation, and sexual dysfunction in the context of the patient’s home situation. Contraception choices require repeated discussion, and every woman needs to be considered as potentially pregnant. During pregnancy, antipsychotic doses should be as low as possible and blood levels frequently monitored. The dose needs to be raised after delivery and the pros and cons of breast-feeding seriously weighed. Mother and infant need frequent monitoring during the postpartum period. Inadequate or overzealous psychopharmacological intervention at this time may jeopardize the mother’s ability to retain custody of her child and may have far-reaching consequences for the life of the mother and child. Optimal prescribing in pregnant women not only will improve patient well-being but also will enhance the safety of their infants and the integrity of the family.

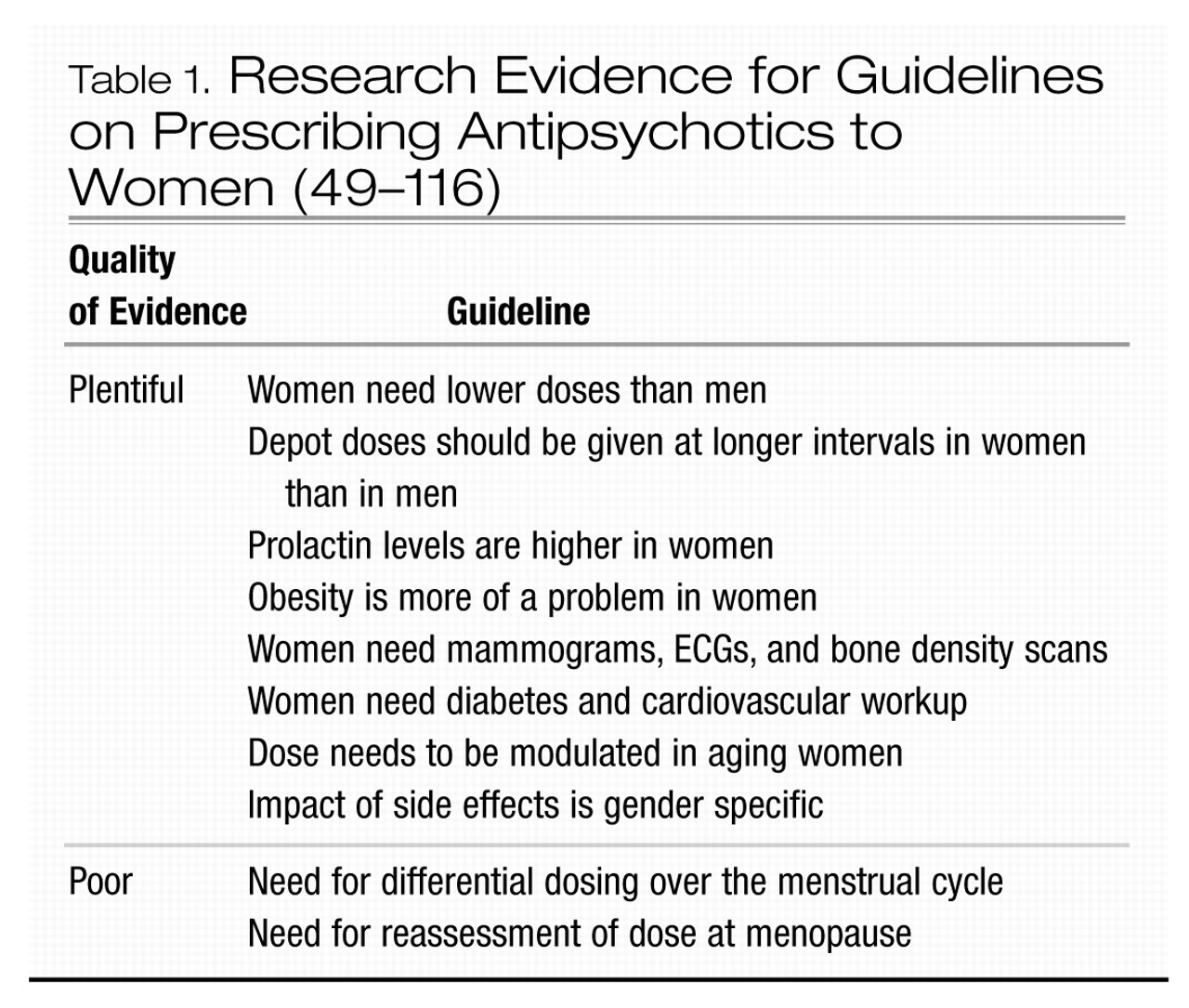

In conclusion, prescribing for a woman is not the same as prescribing for a man (Table 1).