Acts of self-harm and suicide attempts

At the end of the treatment phase, significantly more borderline personality disorder patients who completed the partial hospitalization program (N=13) than control group patients (N=3) had refrained from self-mutilation in the preceding 6 months (p<0.005, Fisher’s exact test). In addition, significantly more partial hospitalization patients than control group patients reported not engaging in self-mutilation after 24 months (90.9% [N=20 of 22] versus 36.8% [N=7 of 19], respectively; p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test), 30 months (81.8% [N=18] versus 31.6% [N=6]; p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test) and 36 months (77.3% [N=17] versus 31.6% [N=6]; p<0.004, Fisher’s exact test). More self-mutilating acts were committed during the 18-month follow-up period by patients in the control group (mean=10.9, SD=11.8) than by patients who completed the partial hospitalization program (mean=0.6, SD=1.6), a difference that was highly significant (Mann-Whitney U=84, p<0.001).

A similar pattern emerged for suicide attempts. At the end of treatment, significantly fewer patients who completed the partial hospitalization program (N=4) than control group patients (N=12) had attempted suicide in the preceding 6 months (p<0.004, Fisher’s exact test). In addition, significantly fewer partial hospitalization patients than control group patients had made a serious suicidal gesture after 24 months (9.1% [N=2] versus 36.8% [N=7], respectively; p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test) and 36 months (18.2% [N=4] versus 63.2% [N=12]; p<0.004, Fisher’s exact test). Fewer suicide attempts were made during the 18-month follow-up period by patients who completed the partial hospitalization program (N=4) than by patients in the control group (N=28), a difference that was again highly significant (Mann-Whitney U=97, p<0.001).

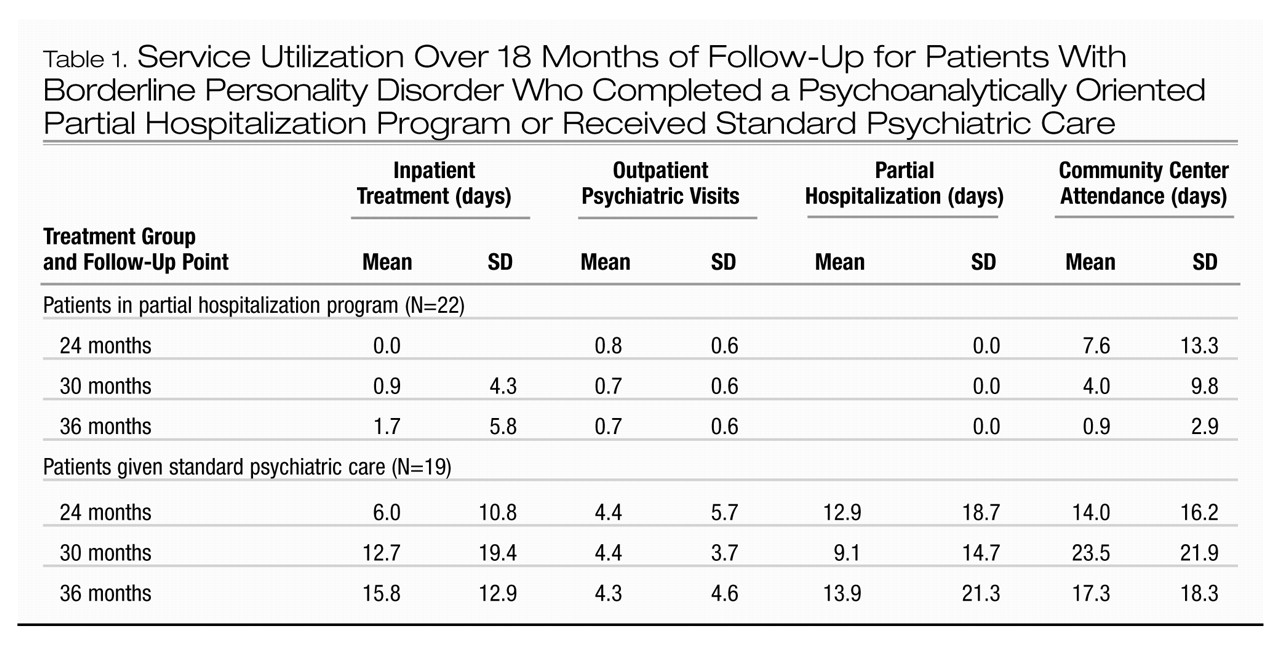

Service utilization

Service utilization data are summarized in Table 1. No patient who completed the partial hospitalization program had been admitted by 6 months after discharge, whereas seven patients who had received standard psychiatric care had been admitted at least once by the 24-month evaluation (p<0.002, Fisher’s exact test). By 1 year after the end of the treatment phase, one partial hospitalization patient had been admitted for 20 days, while seven more control group patients received inpatient treatment (p<0.02, Fisher’s exact test). An additional partial hospitalization patient was admitted twice in the final 6 months of follow-up for 25 and 12 days, while 14 control group patients were admitted during the final 6 months (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Mann-Whitney tests revealed that differences in the average number of inpatient treatment days between the two groups were significant at all follow-up points (24 months: U=143, p<0.005; 30 months: U=138, p<0.007; 36 months: U=72, p<0.001). We examined the variation over the 18 months of follow-up in the number of days in the hospital for patients in the control group (there was little variation over time for those who completed the partial hospitalization program). The repeated measures analysis of variance indicated significant differences between time points of assessment (Wilks’s lambda=0.64, F=4.2, df=2, 16, p<0.03). Exploring the polynomial components of this effect confirmed a significant quadratic effect (F=5.6, df=1, 17, p<0.03) and no significant linear effect (F<1.0, df=1, 17, n.s.).

Mann-Whitney tests revealed that patients who completed the partial hospitalization program had significantly fewer outpatient psychiatric consultations than did the control group patients at all follow-up points (24 months: U=59, p<0.001; 30 months: U=86, p<0.001; 36 months: U=73, p<0.001). Ten patients (52.6%) in the control group received some partial hospitalization treatment during the first 6 months of follow-up (range=3–60 days) as did 36.8% (N=7) during the rest of the follow-up period (range=8–60 days). No patient who completed the partial hospitalization program returned to partial hospitalization care either in the specialist setting or in the general psychiatric setting, which resulted in highly significant between-group differences at all follow-up points (24 months: U=99, p<0.001; 30 months: U=132, p<0.002; 36 months: U=132, p<0.002). Community center visits were measured in number of recorded attendances, which were significantly lower for the partial hospitalization group after the second follow-up point (30 months: U=91.5, p<0.001; 36 months: U=87, p<0.001). While there was a significant decline in the use of community center services in the partial hospitalization group over the follow-up period (Friedman’s χ2=8.4, df=2, p<0.02), a similar decline was not observed in the control group (Friedman’s χ2=3.7, df=2, n.s.).

Six borderline personality disorder patients who completed the partial hospitalization program (27.3%) and 14 control group patients (73.7%) were still taking medication at the end of the follow-up period (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). More important, while 63.2% (N=12) of the control subjects were receiving more than one class of drug (polypharmacy), only 9.1% (N=2) of the partial hospitalization patients were taking mood stabilizers and antidepressants at the end of follow-up (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Cumulatively, 79.0% (N=15) of the control subjects and 36.4% (N=8) of the partial hospitalization patients had received medication during the follow-up period (p<0.007, Fisher’s exact test), with 68.4% (N=13) and 13.6% (N=3), respectively, taking more than one drug (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

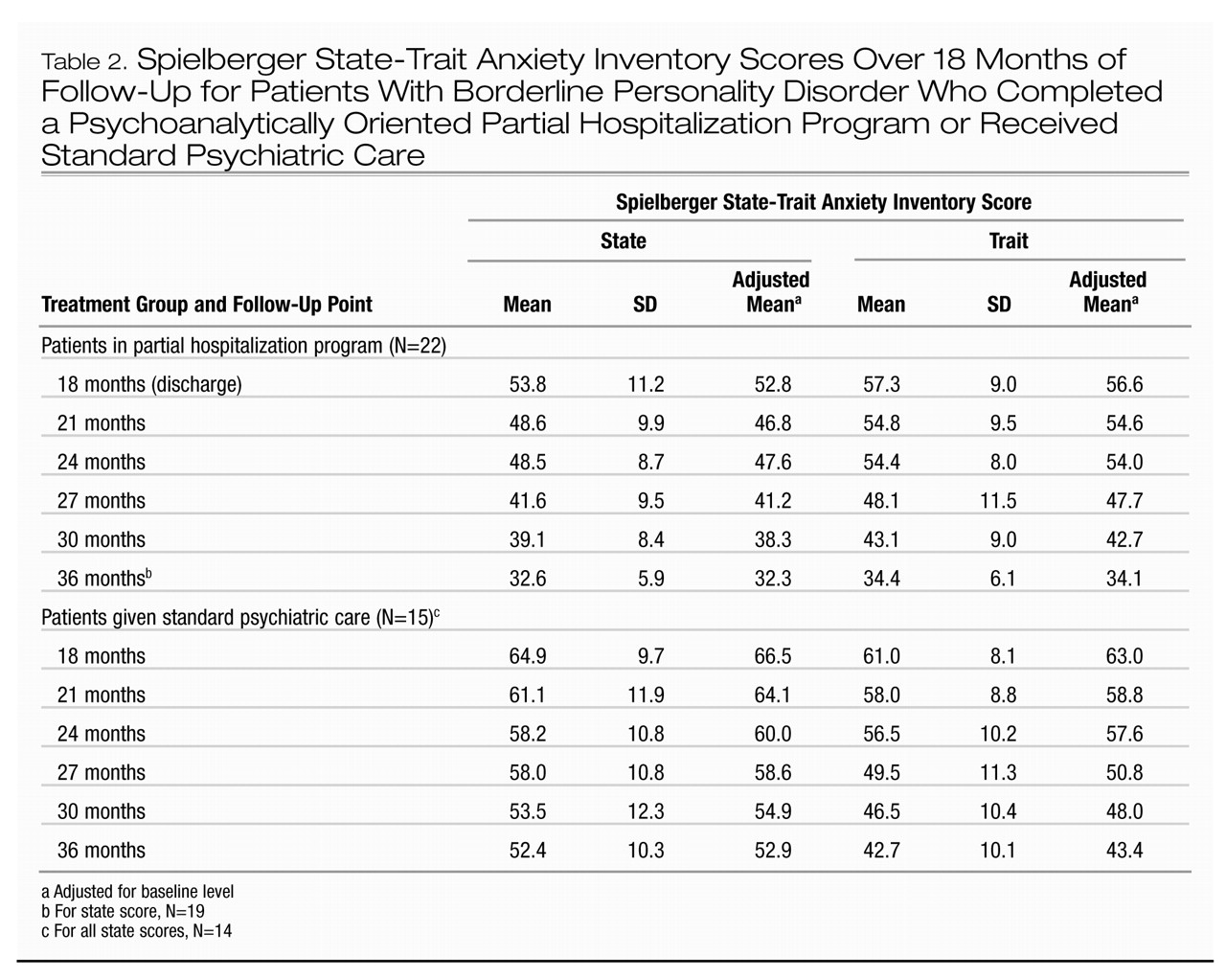

Self-report measures

A multivariate analog of the repeated measures analysis of covariance was applied to mean state and trait anxiety scores (Table 2). There was an overall significant decrease in state anxiety across both groups (Wilks’s lambda=0.70, F=2.5, df=5, 29, p<0.05). The similar pattern of decline was indicated by an insignificant interaction between group and time (Wilks’s lambda=0.73, F=2.1, df=5, 29, p<0.10). Patients who completed the partial hospitalization program scored substantially lower than control group subjects throughout the follow-up period after we controlled for baseline differences. The main effect of group was highly significant (F=34.9, df=1, 33, p<0.001). Pair-wise comparison revealed that the group differences were significant at all follow-up time points (p<0.001). For trait anxiety no significant overall decline was observed (Wilks’s lambda=0.79, F=1.6, df=5, 30, n.s.). The main effect of group only approached significance (F=3.5, df=1, 34, p<0.07), and pair-wise comparisons revealed significant differences at the 18-month (p<0.05) and 36-month (p<0.002) evaluations.

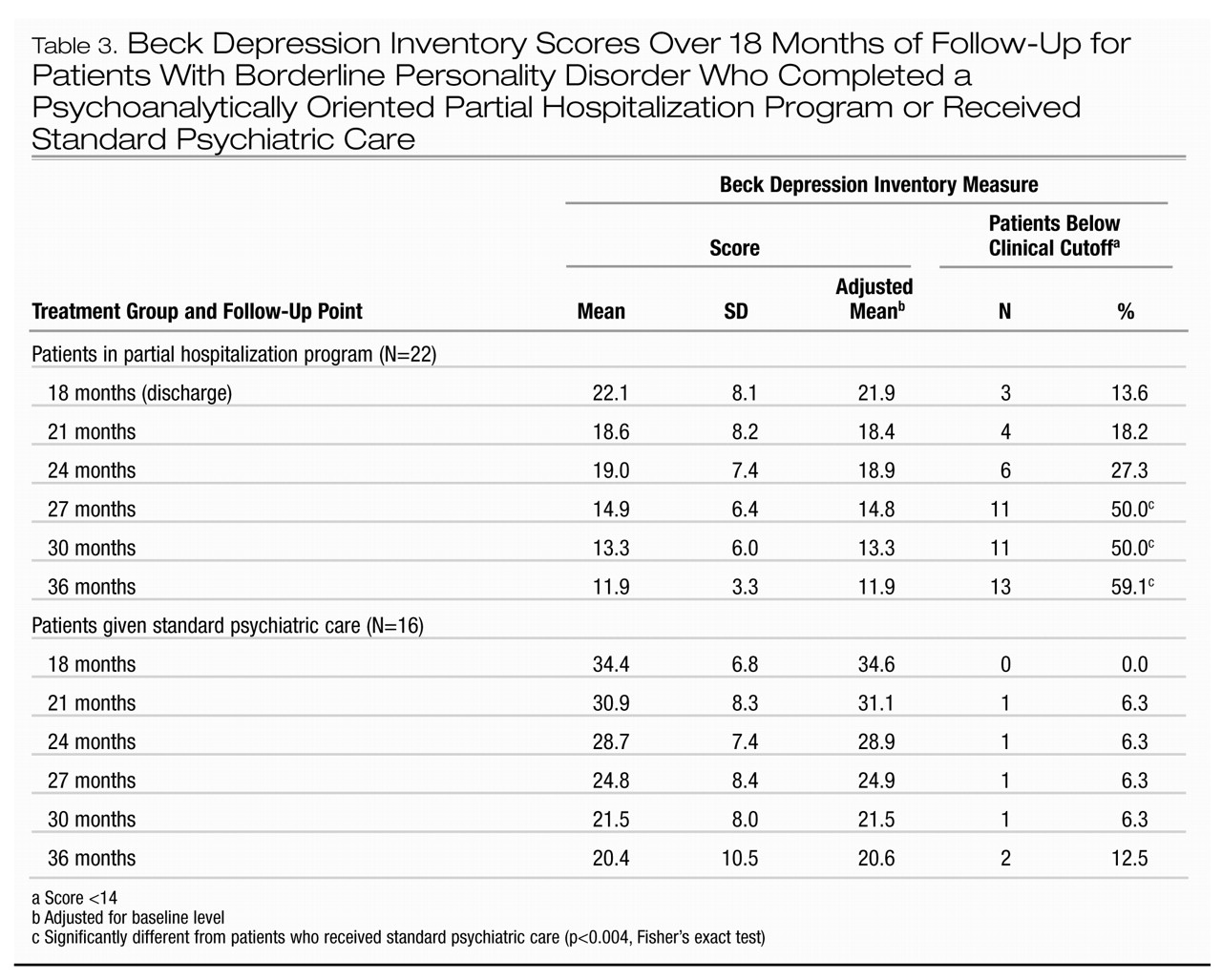

Mean scores on the Beck Depression Inventory are shown in Table 3. ANCOVA revealed no significant main effect of time (Wilks’s lambda=9.25, F<1.0, df=5, 31, n.s.). Patients who completed the partial hospitalization program reported themselves as significantly less depressed than did the control group subjects, and there was a powerful overall group difference (F=32.6, df=1, 35, p<0.001). The rate of decline in the two groups was comparable, and the group-by-time interaction was not significant (Wilks’s lambda=0.84, F=1.1, df=5, 31, n.s.). Pair-wise comparison revealed significant differences (p<0.001) in Beck Depression Inventory scores at all assessment points. At the end of the treatment phase, only three partial hospitalization patients and none of the control group subjects were below the clinical cutoff on the Beck Depression Inventory. The proportion of partial hospitalization patients who scored below 14 increased over the follow-up period, with significant between-group differences seen at the 27-, 30-, and 36-month evaluations (Table 3).

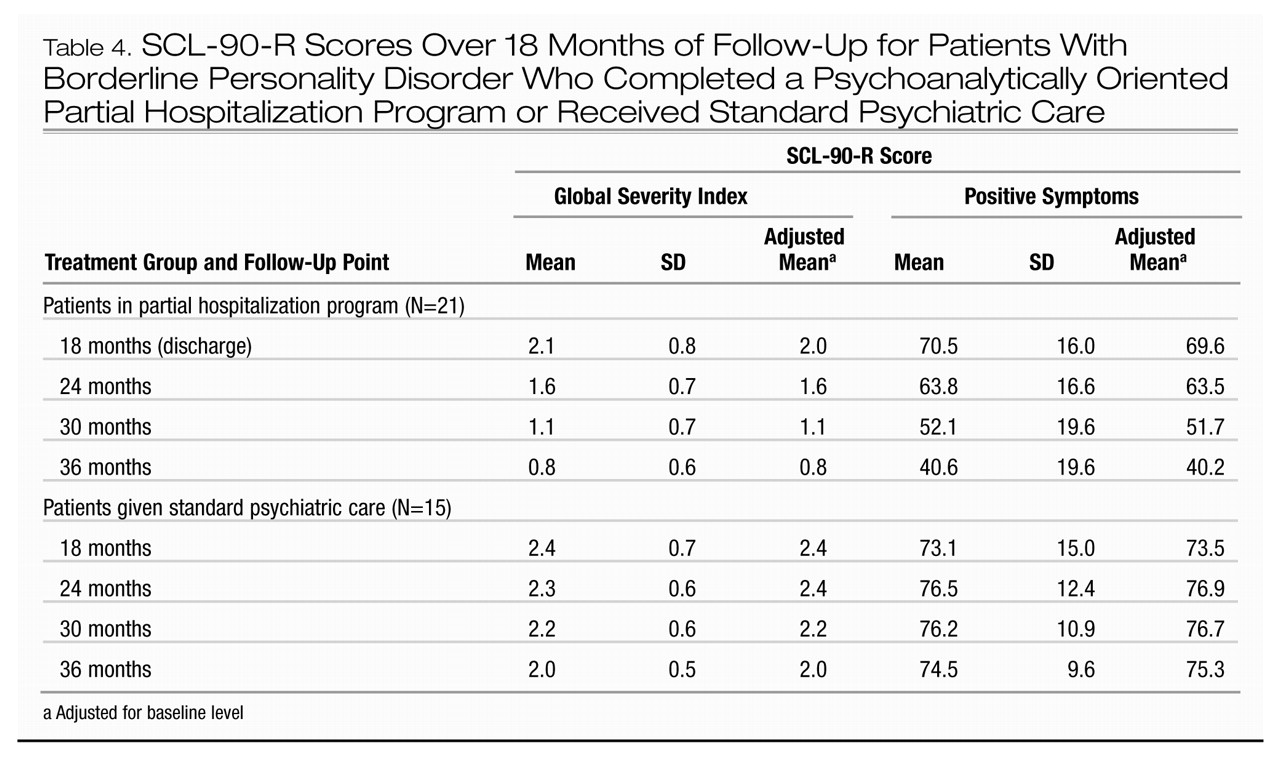

The mean scores on the global severity index scale of the SCL-90-R are summarized in Table 4. Overall, patients who completed the partial hospitalization program obtained significantly lower scores than did the control group patients (F=30.2, df=1, 33, p<0.001). There was a significant group-by-time interaction (Wilks’s lambda=0.59, F=7.3, df=3, 31, p<0.001). Polynomial decomposition of this interaction revealed a highly significant linear effect (F=19.4, df=1, 33, p<0.001), indicating that the increase in disparity between the two groups over the follow-up period was statistically significant. Pair-wise comparisons showed that global severity was not significantly different at the end of the treatment phase but was significantly lower for the partial hospitalization patients at the 24-month evaluation (p<0.001) and remained significantly lower throughout the follow-up period at the same level of significance.

Mean positive symptom scores are also summarized in Table 4. The main effect of group was highly significant (F=26.7, df=1, 33, p<0.001). The group-by-time interaction was also significant (Wilks’s lambda=0.54, F=8.9, df=3, 31, p<0.001). Polynomial decomposition showed a highly significant linear effect (F=27.6, df=1, 33, p<0.001). Pair-wise comparisons were not significant at the end of the treatment phase but were significant at the 24-month evaluation (p<0.01), and the difference increased over the follow-up period (p<0.001) as the number of reported symptoms declined in the partial hospitalization patients but remained constant in the control group.

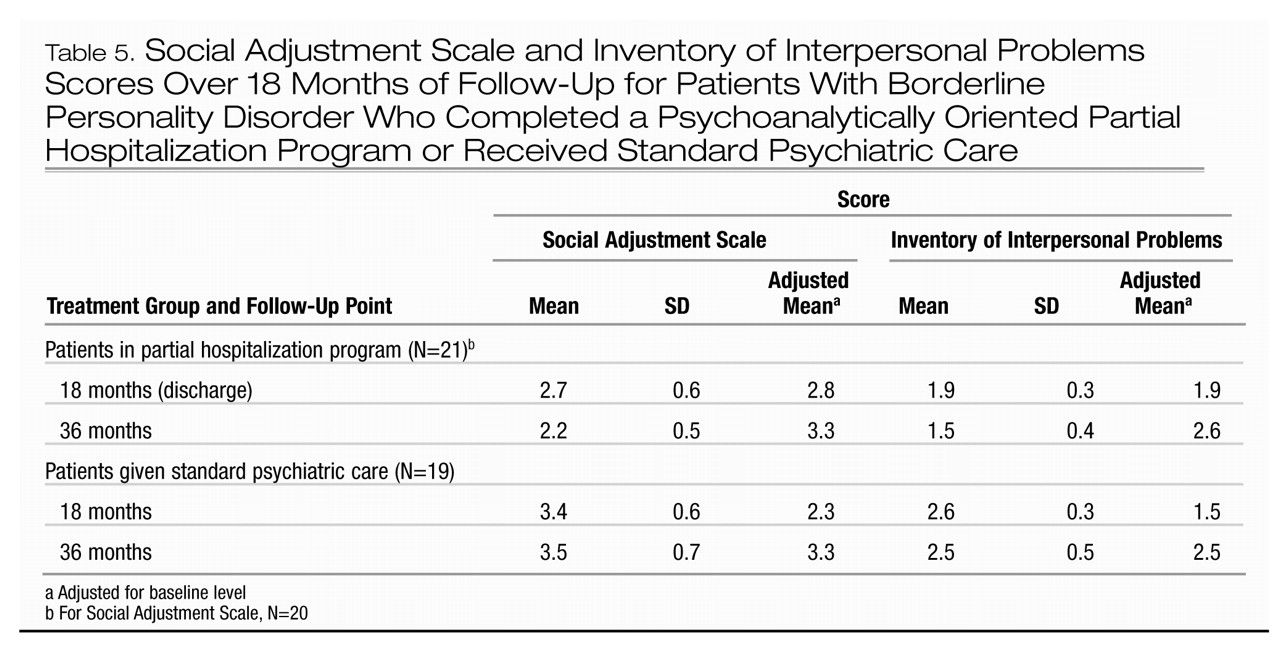

The mean scores for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems and the Social Adjustment Scale at the end of the treatment phase and the end of the follow-up period are summarized in Table 5. The differences between the groups were marked at posttreatment and increased over the follow-up period. The repeated measures ANCOVA performed on the posttreatment and follow-up data with pretreatment measure as covariate revealed a substantial group main effect (F=92.3, df=1, 37, p<0.001). The between-subject and repeated measures factor interaction was also significant (Wilks’s lambda=0.87, F=5.4, df=1, 37, p<0.03), indicating that the observed lowering of interpersonal problems over the follow-up period was statistically significant relative to the lack of change in the control group over the same period. Similarly, social adjustment problems reported on the Social Adjustment Scale improved during follow-up. The difference was significant both at posttreatment and at the 36-month evaluation. The ANCOVA (pretest Social Adjustment Scale total scores as covariates) yielded a significant group main effect (F=25.2, df=1, 36, p<0.001) as well as a significant interaction between group and time factors (Wilks’s lambda=0.86, F=6.0, df=1, 36, p<0.02).