The field of capacity assessment is dominated by a fundamental tension between two core ethical principles: autonomy (self-determination) and protection (beneficence;

Berg, Appelbaum, Lidz, & Parker, 2001). What should we do when an older adult, particularly one who is frail, vulnerable, dementing, or eccentric, begins to make decisions that put the elder or others in danger, or that are inconsistent with the person's long-held values? At what point does decision making that is affected by a neuropsychiatric disease process no longer represent “competent” decision making? These are some of the essential, and perplexing, questions of clinical capacity assessment.

We use the term

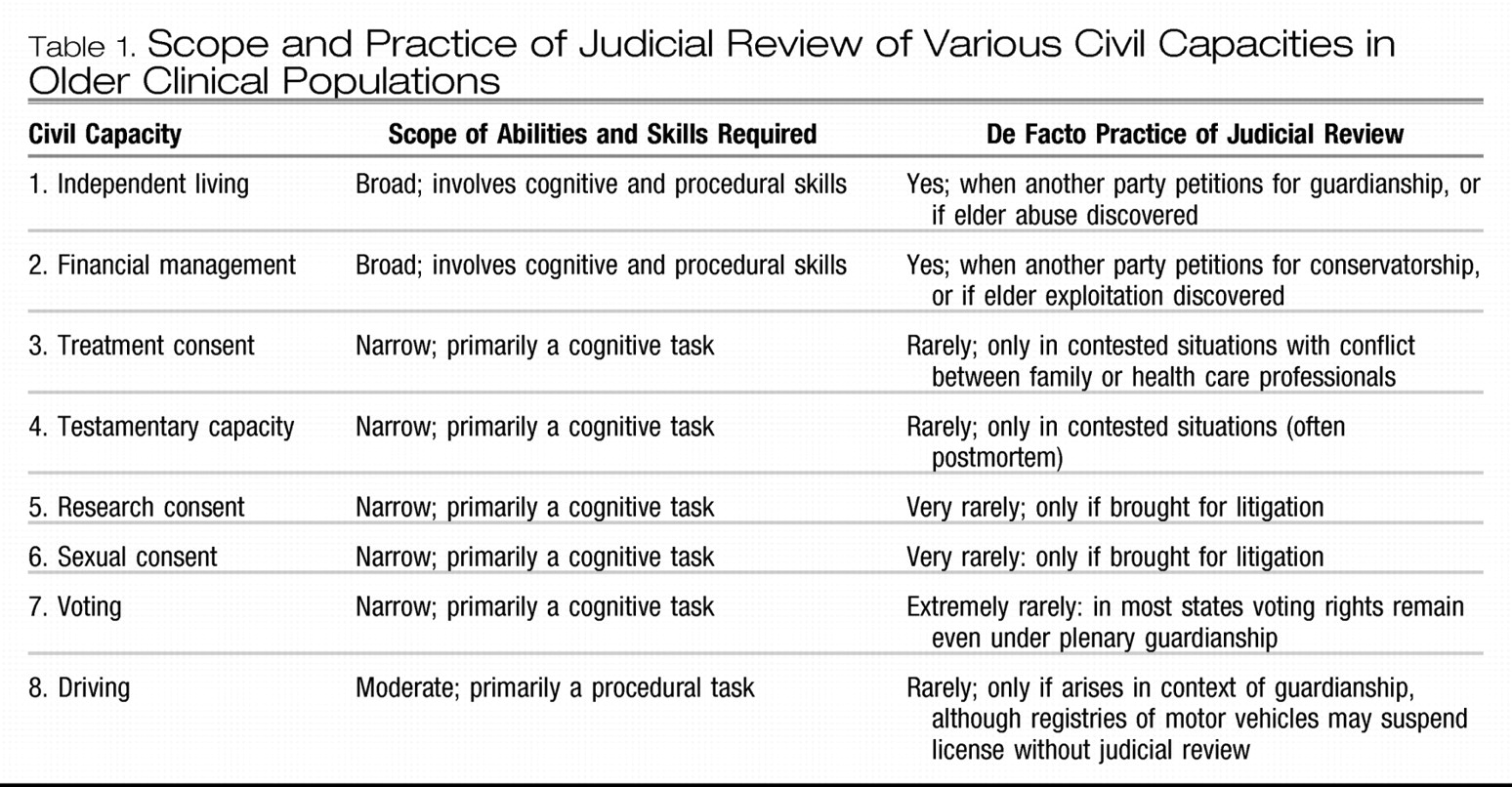

capacity to refer to a dichotomous (yes or no) judgment by a clinician or other professional as to whether an individual can perform a specific task (such as driving or living independently) or make a specific decision (such as consenting to health care or changing a will). There are at least eight major capacity domains of relevance to older adults with neuropsychiatric illness, as presented in

Table 1. Two of these require a broad set of cognitive and procedural skills—independent living and general financial management. Other capacities, such as treatment consent, testamentary capacity (wills), research consent, sexual consent, and voting, are generally narrower in scope, focusing on one or a small number of specific decisions requiring an underlying set of cognitive abilities. These narrow capacities, although technically legal capacities, are rarely subject to judicial review.

Decisions about capacity are ultimately legal judgments enforced by the power of the state. However, in practice, the majority of determinations of diminished capacity are probably made outside of the courtroom, by clinicians, attorneys, adult protective service workers, and other professional groups working with the elderly population. As noted in

Table 1, situations requiring guardianship or conservatorship are resolved in a court of law, and they require a legal determination regarding competency. However, in such cases where there exists a previously appointed surrogate (such as a health care proxy), the authority of the surrogate springs into effect on the basis of a clinical finding of diminished capacity without judicial review. Further, in practice, many situations of diminished capacity are managed without any formal determination of incapacity or appointment of a surrogate. For example, a caregiver to an adult with dementia may simply assume responsibility for bill paying and investments, or strategically disallow driving. Thus families are often the arbiter of judicial involvement, seeking court authority in situations that cannot be managed through less restrictive alternatives. This somewhat fuzzy line between the family, the clinical role, and judicial role in managing diminished capacities in older adults can create considerable confusion but is important to recognize (

Ganzini, Volicer, Nelson, & Derse, 2003).

In this article we consider civil capacity assessment of older adults as a growing field of clinical practice and empirical research. We note the sociodemographic forces that are driving the new prominence of capacity assessment, discuss cross-disciplinary interest in capacity assessment, and describe the emergence of capacity assessment as a distinct field of practice and research. We then review existing research in the two important clinical domains of medical decision-making capacity and financial capacity, and we outline an agenda for future research.

DEVELOPMENT OF CAPACITY ASSESSMENT INSTRUMENTS

The development of objective instruments to measure capacity has been integral to the emergence of the capacity assessment field. In the earlier part of the 20th century, incapacity was determined on the basis of the presence of a diagnosis alone, and perhaps some global indication of mental status. A critical conceptual and legal development has been the shift away from diagnosis to the consideration of key functional abilities relevant for specific capacity domains (

Grisso, 2003). The emphasis on function has sparked efforts at developing standardized instruments to empirically measure skills in these domains. Among these instruments are those produced by the MacArthur Group to assess capacity to consent to treatment (

Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998b) and research (

Appelbaum & Grisso, 2001), by Marson and colleagues to assess capacity to consent to treatment (

Marson, Ingram, Cody, & Harrell, 1995) and financial decision making (

Marson et al., 2000), as well as instruments to assess the capacity to live independently (guardianship;

Anderer, 1997;

Loeb, 1996). Several recent reviews summarize the properties and uses of various instruments (

Moye, 2003;

Moye, Gurrera, Karel, Edelstein, & O'Connell, 2006;

Sturman, 2005).

Standardized capacity assessment instruments aim to improve upon the notorious low reliability of more general clinical examinations (

Markson, Kern, Annas, & Glantz, 1994;

Marson, McInturff, Hawkins, Bartolucci, & Harrell, 1997;

Rutman & Silberfeld, 1992) by focusing clinical assessment on the most relevant functional skills. They are meant to supplement but not supplant clinical judgment about capacity. Because of the interactive and contextual nature of capacity, a test score alone cannot substitute for a professional clinical judgment (

Kapp & Mossman, 1996). A significant challenge in the development of such instruments is that there is no generally accepted criterion validity standard for capacity. Therefore, capacity assessment instruments are validated through construct validation (

Moye, 2000) by a consideration of the convergence of various approximate indicators of validity, namely, the finding of incapacity in populations who are expected to have diminished capacity and the consistency of measurement over time and methods—such as the association between two measures of capacity, or the association of a capacity measure and cognitive tests.

CAPACITY ASSESSMENT IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Capacity assessment of older adults will become increasingly important over the coming century. Our aging society has a very strong interest in being able to accurately discriminate intact from impaired functioning in the older adult population (

Marson, Sawrie, et al., 2000). The convergence of increased longevity, cognitive aging and dementia, blended families, and the intergenerational transfer of wealth in our individualistic society are making, and will continue to make, issues of capacity loss in older adults a prominent public policy concern.

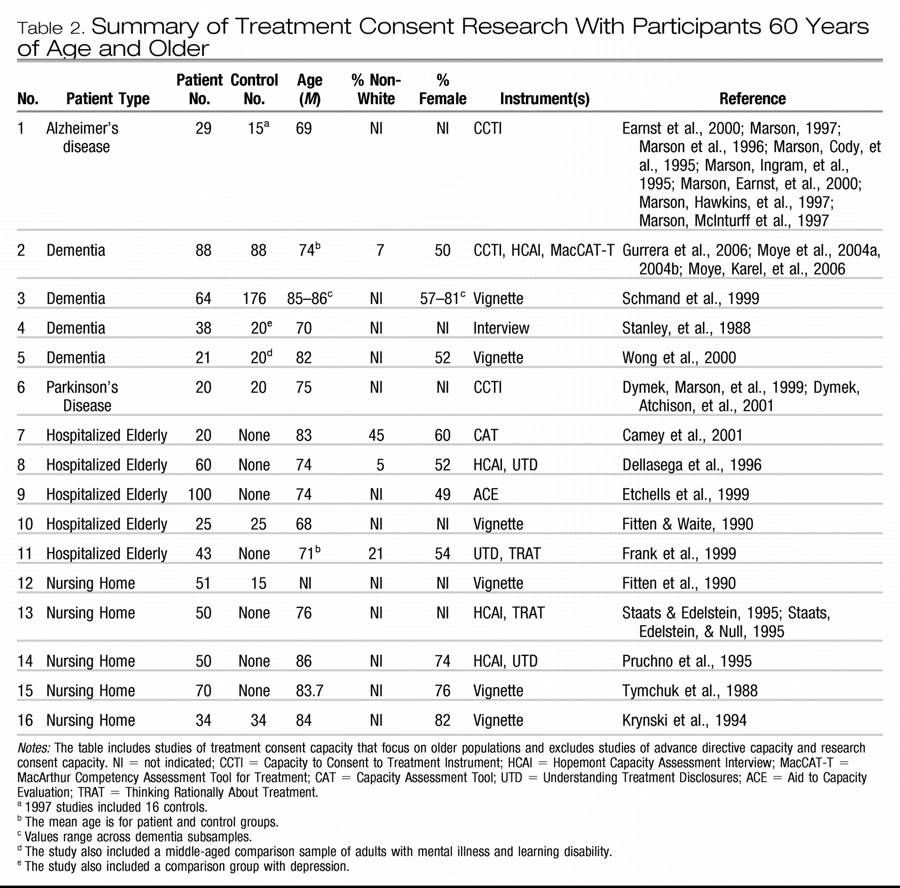

The past 10 years has witnessed the emergence of capacity assessment in aging as a field of study, with a growing body of empirical studies, a promising first generation of capacity assessment instruments, and a small but growing cadre of scientific researchers. Two clinical areas that have received the most research attention are treatment consent capacity and financial capacity. These studies await replication, but they provide a departure point for expanded explorations of other capacity constructs.

For example, a critical area concerns the assessment of capacity to live independently, which is the basis for judgments of guardianship in probate court. This capacity comprises a domain so vast it can include almost all areas of functioning, and it may manifest itself in poorly understood behaviors such as “self-neglect” and with extreme unsanitary living conditions (

Moye, 2003). Another key area requiring attention is testamentary capacity and the related issues of undue influence and exploitation of older adults with diminished capacity. Undue influence is a concept that appears in the law, but is not well defined clinically. It generally relates to some form of coercion of a vulnerable adult to do something that will benefit the coercer. These are increasingly common forensic issues in the courts, which unfortunately have correspondingly very little literature or knowledge from the psychological sciences to draw upon (

Marson, Huthwaite, & Hebert, 2004). Two other areas that are almost without study are sexual consent capacity and voting capacity. The sexual consent issue arises with two older adults living in an institution who are intimate and at least one of whom has questionable capacity to consent to a sexual relationship (

Lichtenberg & Strzepek, 1990). The recent presidential elections have highlighted the issue of voting capacity, particularly in patients with advanced dementia (

Appelbaum, Bonnie, & Karlawish, 2005).

In addition to considering a wider range of capacities, it will be important for researchers to characterize the nature of capacity impairment within a wider range of older patient groups. For example, studies might focus on capacity impairment within dementia subtypes (AD, PD, diffuse Lewy body disease, and frontal lobe dementia), and within other neuropsychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and profound depression. Capacity issues in developmental disorders such as mental retardation and autism in older adults should also be explored. In short, we need to understand how capacity issues present in older adults across the spectrum of neuropsychiatric and developmental syndromes.

A third area for study is clinician decision making. Capacity assessments are ultimately human judgments occurring in a social context. It is therefore crucial that we understand how clinical judgments of decisional capacity relate to the social dynamics of decision making. We need more studies that look at how clinicians integrate multiple sources of capacity data with the elder's situation and values, and at the interrater reliability of clinician capacity judgments. These studies should also explore how clinicians from different disciplinary backgrounds may vary in their capacity assessment approach and outcomes.

A fourth area of empirical study involves identifying cognitive and other behavioral markers of diminished capacity. Neuropsychological studies of decisional capacity in dementia have provided important initial findings concerning the neuro-cognitive changes in the brain that presumably mediate loss of capacity, and that appear to strongly underlie the competency construct. Such studies will provide an empirical basis for clinicians to assess capacity and to predict future decisional abilities and needs of older adults for caregivers and families, attorneys and judges, and public health officials.

A solid empirical research base will be necessary to ensure the quality and accuracy of capacity determinations in the coming century. Capacity is a construct with clinical, ethical, and legal referents, and in this regard it may be unique among clinical constructs. Although a clinician's opinion is currently the accepted clinical standard for capacity determination—there is no “gold” standard—clinical judgments of capacity can often be inaccurate, unreliable, and even invalid. Thus, capacity assessment training should become a part of the clinical training of physicians, psychologists, and other health care professionals working with the elderly population (

Karlawish & Schmitt, 2000;

Marson, Sawrie, et al., 2000).

Finally, the many intersections of law and clinical practice in this area require more examination. Capacity research poses some unique challenges in that research design must, necessarily, be linked to legal definitions of capacity, as capacity is ultimately a legal matter. Yet the law is more a matter of social consensus than science, and as such it forms an unusual basis for scientific study (

Moye, 2000). Thus a dynamic approach must be pursued in which science is based on but not restricted by law and, one would hope, subsequently informs the law.

Accordingly, studies are needed of the relationship between legal and clinical models of capacity, and of the relationship between clinical assessments and juridical actions (e.g., what kind of capacity assessments lead to optimal judicial orders). An important goal of clinical capacity assessment is to assist judges and other legal professionals in crafting legal interventions that are specifically tailored to the needs of individual clients, and that clearly identify needs for protection while simultaneously protecting rights in areas of preserved capacity. Within the law, there is a growing movement away from full (plenary) guardianship orders to limited orders that provide surrogate controls only in needed areas. Thus vigorous interdisciplinary collaboration between legal and clinical professionals, and also public policy makers, is vital to the continuing development of capacity assessment as a field, and to its success as a societal mechanism for resolving individual issues of autonomy and protection.