The real trouble is taking my phosphate binders. I carry them around with me, but this thing of opening a bag, taking pills, that's hard to do. Every time I have to take a pill in order to eat at McDonald's, it feels like I'm being punished.

—Dialysis patient, noncompliant with renal

dietary restrictions

Demoralization is one of the most common reasons why psychiatrists are consulted for medically ill patients, with a request typically posed as, “Please evaluate and treat depression.” Demoralization refers to the “various degrees of helplessness, hopelessness, confusion, and subjective incompetence” that people feel when sensing that they are failing their own or others' expectations for coping with life's adversities (

1, p. 14). Rather than coping, they struggle to survive.

Demoralization occurs so commonly that it can be regarded as a universal human experience. Analogous to bereavement, demoralization can result from a myriad of life's insults other than medical illnesses. Slavney has argued that demoralization is properly regarded not as a psychiatric disorder but as a normal human response to overwhelming circumstances (

2). Yet frequently other physicians ask psychiatrists to intervene.

DISTINGUISHING DEMORALIZATION FROM A DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Demoralization is commonly confused with depression, with which it shares disturbances in sleep, appetite, and energy and even suicidal thinking. It differs from major depressive episode, however, because responsivity of mood is usually preserved, in that cessation of adversity rapidly restores a capacity to feel enjoyment and to hope. This is the case whether the relief is physical, as with improved control of pain, nausea, or insomnia; or emotional, as with the happy appearance of a friend or unexpected good news about the medical prognosis. De Figueiredo proposed that subjective incompetence due to uncertainty over what course of action to take distinguishes demoralization from depression, in which apathy predominates even when a needed action is clear (

3). Demoralization also differs from depression in that it generally fails to show robust improvement when antidepressant medications are prescribed. This is an important distinction in an era when both primary care physicians and psychiatrists often respond first to a patient's distress by prescribing a pill. Rather, demoralization is best countered by either 1) ameliorating physical or emotional stressors or 2) strengthening a patient's resilience to stress.

Acknowledging suffering and restoring dignity are potent in strengthening a patient's resilience to stress. Slavney has proposed conversing in a manner that normalizes a demoralized patient's distress (

4). He has suggested that a clinician ask first about mood (“How are your spirits today?”) and the patient's concerns (“What is the most difficult thing for you now?”) and then validate the patient's distress as that of a normal person responding to abnormal, hard circumstances (

2). Viederman has shown how an empathic dialogue can help a patient to express and understand difficult emotions and grasp their significance in terms of the patient's life narrative (

5,

6). Weingarten has described compassionate witnessing as a social and cultural process vital for maintenance of hope (

7,

8). In this article, we describe how focused bedside interviews can build on these interventions by mobilizing specific existential postures of resilience.

BREAKING DOWN DEMORALIZATION INTO ITS EXISTENTIAL COMPONENTS

The term “demoralization” is often used as if describing some singular state of being. However, demoralization can be more usefully regarded as a compilation of multiple existential postures evoked by the medical crisis in which a patient is immersed. Viewing demoralization in terms of distinct existential components is pragmatically useful because it can help a clinician to ask more specific questions for mobilizing an assertive response to illness.

Existentialist philosophers of the 19th century and early 20th century discussed such experiences as suffering, despair, meaninglessness, and a sense of isolation as the boundaries of human existence, in that every person is obligated to encounter and to respond to each of them (

9,

10). Subsequent existentialist psychiatrists and psychologists elaborated psychotherapies based on associations noted between anxiety, depression, and patients' dread of these existential crises (

11,

12). Recent decades of psychosomatic research further extended this understanding by demonstrating how existential crises involve not only the mind and spirit but also the body.

States of being associated with existential crises are markers for the junctures where the physiological and psychosocial worlds most definitively meet. They are both distinctive experiential states and indicators for physiological dysregulation. There are research literatures linking such states as despair, helplessness, and a sense of isolation with vulnerability to a range of physical diseases, including cardiovascular disease and cancer (

13–

16). These same states are reliable triggers for the onset or relapse of axis I psychiatric disorders, whether psychoses, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, or dissociative disorders.

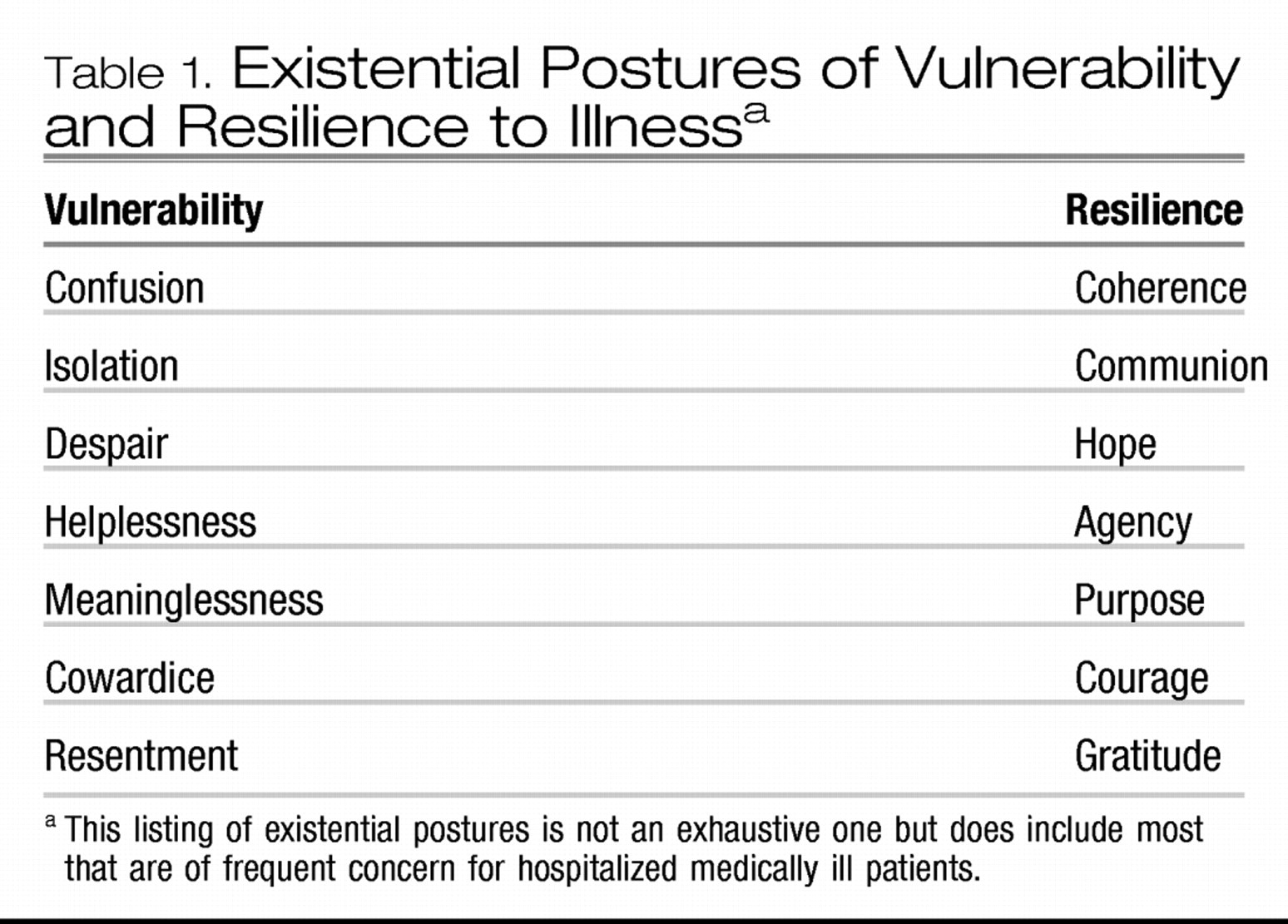

Dimensionally, existential states can be regarded as postures turned relative degrees toward, or away from, assertive coping with illness. Those in the left-hand column of

Table 1 represent states of breakdown in goal-directed coping (

17). They set the stage for withdrawal from active engagement with living. Confusion, despair, helplessness, and related states each help constitute a readiness to quit responding to challenges, whether mental or physical. The existential postures in the right-hand column represent an effort to meet challenges and to embrace life with all its circumstances. Mindfulness for these polarities can guide bedside interviewing toward helping patients sustain these existential postures of resilience as much of the time as is possible (

1).

Helping patients to sustain existential postures of resilience is done by whatever means creativity can devise: convincing the attending physician to sit down at the bedside for a discussion with the patient about the medical diagnosis and its prognosis; cajoling the medical team into providing more aggressive pain management; responding to the patient as a normal person dealing with abnormal circumstances; helping to mobilize contact with friends or family who have lost track of the hospitalized patient. We focus here on methods of bedside interviewing that can help mobilize existential postures of resilience.

COHERENCE VERSUS CONFUSION

Confusion, an inability to make sense of one's situation, disables all forms of assertive coping. Confusion commonly occurs among patients in general hospitals as the salient symptom of delirium, in which metabolic brain abnormalities disturb perception, concentration, memory, and higher cortical functions. However, confusion also arises for cognitively intact patients when a definitive medical diagnosis cannot be established, a medical disorder does not respond in expected ways to treatment, or different medical team members give conflicting communications to the patient (

8,

17).

(pp.292–297) Questions that can help a patient to regain a sense of coherence include the following:

•.

How do you make sense of what you are going through?

•.

When you are uncertain how to make sense of it, how do you deal with feeling confused?

•.

To whom do you turn for help when you feel confused?

•.

[For a religious patient] When you feel confused, do you have a sense that God has a way of making sense of it? Do you sense that God sees meaning in your suffering?

The most useful questions are often those in which the clinician in essence lends to the confused patient the clinician's executive functions for organizing, planning, and judging by embedding them within questions:

Ms. A was a 32-year-old woman with recurrent lymphoma for whom a bone marrow transplant had failed. She complained that her oncologist was not adequately addressing her pain. She was also angry that he disagreed with her wish to stop chemotherapy. She felt alone and uncared for and added spontaneously, “Why can't everyone leave me alone so I can die?” She was visibly confused and overwhelmed.

After listening for a few moments, the psychiatric consultant said, “I've heard you mention four main areas of concern—arranging a consultation at another cancer center for a second opinion, your feelings of depression, the physical pain, and whether or not to continue with cancer treatment. Are there other things that should be on the list?” When she said, “No,” the consultant asked her to put these four items in order of their concern to her. Ms. A gave highest priority to controlling pain and then listed arranging the consultation for a second opinion and then dealing with depression. Whether to continue chemotherapy was actually a distant fourth.

The consultant wrote down the list and handed it to her. She suggested that Ms. A hold it during her meeting with her oncologist that afternoon so she could stay focused on what she wanted to accomplish. As the conversation progressed, Ms. A stopped holding her head, rocking, and shifting her position as if in pain. The consultant asked if she felt less anxious. Ms. A responded more assertively, “I can think more clearly. Now I have a plan.” She later reported that, although her oncologist “still didn't get it,” she felt that she could continue chemotherapy.

COMMUNION VERSUS ISOLATION

Communion is the felt presence of a trustworthy person. It is evidenced by the nuanced language we possess for describing its different expressions: making contact, acknowledgment, feeling heard, witnessing, intimacy, community. Theologian Henri Nouwen observed about men who had survived long jail terms that “a man can keep his sanity and stay alive as long as there is at least one person who is waiting for him. … And no man can stay alive when nobody is waiting for him.” (

18)

(p.66)Medical illness is profoundly isolating for many people. An illness cannot be fully experienced by other people, even when they are sympathetic. Illness removes a person from both familiar routines and the special pleasures of living with other people. It sometimes isolates harshly through stigma from disfigurement or fears of contagion. Isolation is a distinctive accompaniment of physical pain, when that which feels most real in one's body is invisible to others. Questions that can initiate steps toward communion with others include the following:

•.

Who really understands your situation?

•.

When you have difficult days, with whom do you talk?

•.

In whose presence do you feel a bodily sense of peace?

•.

[For religious patients] Do you feel the presence of God? How? What does God know about your experience that other people may not understand?

Mr. B was a 51-year-old man who was hospitalized for AIDS and pneumocystis pneumonia. Psychiatric consultation had been requested to treat his depression and to assess his risk for suicide. After summarizing the psychiatry resident's initial assessment, the consultant commented, “This is a hard illness to go through. How well are you keeping your spirits up?”

“Not very well,” Mr. E. responded. “Sometimes I really would like to leave this world.”

“At those times, what helps you find a will to live?” the consultant asked.

“My mother and brother came to visit me yesterday,” he said.

“Your relationships with your mother and brother help you find a will to live?” the consultant reflected back.

“Yes. And my AA group,” he added.

“I wondered about that. I knew you were in AA but wondered whether you just dropped into different groups, or whether you had a sponsor and close relationships.”

“They visit me every day,” he responded.

“So they are a real community for you. You choose to live for your relationship with them, and they with you?” the consultant asked.

“Yes.”

Mr. B told how he had many troubles and disappointments in his life—acknowledging that he was gay, going through divorce, dealing with alienated children, living with HIV and AIDS, feeling used and exploited by different friends and partners. “But when I began going to AA, I learned that people in AA would not hurt me.”

The consultant asked whether there were other sources from which he drew hope and purpose for his life.

“Well, I've tried relying on religious beliefs, but that hasn't worked very well.” He said that he had grown up as a Catholic but had never been able to believe in God.

“I'm supposing that in AA, your relationship to a Higher Power is important. Is that different from the God of the Catholic Church?” the consultant asked.

“AA is my Higher Power,” he responded.

“This community—these relationships with those in your AA group—they are your Higher Power?” the consultant asked for clarification.

“Yes,” he said. He then told how someone had come unexpectedly the day before to see him, which was a good surprise.

While medications were recommended to address Mr. B's sleep and anxiety symptoms, the primary recommendation from the psychiatric consultation was that his supportive network of AA community and his family members be integrated more fully into his care.

HOPE VERSUS DESPAIR

Despair, or hopelessness, has predicted coping failure in research studies (

14). Hope is essential both for discerning present desires and for making future plans. Questions that help mobilize a sense of hope include the following:

•.

From what sources do you draw hope?

•.

On difficult days, what keeps you from giving up?

•.

Who have you known in your life who would not be surprised to see you stay hopeful amid adversity? What did this person know about you that other people may not have known? (

19)

Mr. C was a 48-year-old man who had been admitted to the hospital 72 hours earlier because of weakness in his arm and leg that had progressed over several days. He entered the hospital fearing that he had had a stroke. After a chest X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging scan of his brain, however, he reported being told, “You have stage-four cancer and it has metastasized to your brain.” He responded by feeling that “it's the end of the race,” and he told a nurse that he was going home to shoot himself with his gun. The on-call psychiatry resident, asked to evaluate Mr. C's risk for suicide, determined that he was in shock over the news and angry over its mode of delivery but not at imminent risk of self-harm.

Mr. C was a mathematician who always focused on statistical odds. Knowing the low likelihood of cure for his cancer deepened his despair. He had no past history of a mood disorder, however, and his score of 10 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was not significantly elevated.

The psychiatric consultant asked how he wished that the medical team would have spoken when reporting such bad news. “I would have picked a time when I wasn't in so much physical pain, getting stuck with needles and IVs. It made a lot of difference when they started doing what they said they would do. For 2 days, they stood around talking about radiation therapy, and now they are finally doing it.”

Recalling that Mr. C stayed aware of the betting odds, the consultant asked how he managed to stay in an emotion of hope even though he knew the odds were long against him. “I'm able to look at the whole spectrum, then to decide what position to take.”

“Many people can't do that,” the consultant noted. “When the odds are long, they feel too overwhelmed. How have you learned to do this?”

“There are people who go to Las Vegas with ten dollars and win $300,000,” Mr. C responded. “I know of one woman who was given a terminal diagnosis of cancer, but she is still alive.”

“So you do know some examples, stories, and analogies that you can draw from to sustain a realistic sense of hope. When in your life did you learn to do this, or who did you learn it from?”

“Different people are good at different things,” he said, explaining that his years of work in industry had centered on making decisions about which new products to invest in and for how long and when to give up on one and turn to another that showed more promise.

“It sounds like this is something that makes you good at your work, and now you are bringing your skill to confront this illness,” the consultant commented.

Through the remainder of his hospitalization, Mr. C maintained a sense of humor and focus on the future.

PURPOSE VERSUS MEANINGLESSNESS

Suffering without meaning is unbearable. Yet many who suffer enough to desire death instead choose to live because they have strong purposes for living. Physical illness is a challenge because it can make a purposeful life not only difficult to conduct but even difficult to imagine. This is particularly so when medical disabilities end productive work or pleasurable activities that had been vital for life's meanings. Reconstruction of a robust purpose for living is often a key step in rehabilitation. Questions for starting a generative inquiry about purpose include the following:

•.

What keeps you going on difficult days?

•.

For whom, or for what, does it matter that you continue to live?

•.

[For terminally ill patients] What do you hope to contribute in the time you have remaining?

•.

[For religious patients] What does God hope you will do with your life in days to come?

Mr. D was a 45-year-old man with severe degenerative spinal disk disease. A complex regimen of an antidepressant, a psychostimulant, and multiple analgesics only partially relieved his chronic pain. In addition, he recently had been placed on disability and was financially stressed. Psychiatric consultation had been requested to assess his risk for suicide.

Mr. D said he wondered now whether life was still worth living. He denied having a plan for suicide but acknowledged spending a recent evening on the Internet looking at suicide web sites.

“What holds you back?” the psychiatric consultant asked.

“The efforts that my doctors and a few other people have made to get me as far as they've been able,” he responded. “I don't want to let them down.” He named four people who had most helped him rally after he had become despondent.

Then he added, “I've always spent my time helping other people.” The consultant asked what he meant.

“All my work has been for other people—nonprofit organizations, public service. I've always worked in the government.” He told how he not only had worked long hours in his government job but also had volunteered time for community service projects and nonprofit advocacy groups.

“It sounds like a strong sense of purpose from your work life has been important,” the consultant said. “It has mattered a lot to know that what you do makes a difference in people's lives.”

Mr. D agreed, adding that it had been a mistake to stop working. Then he described his current dilemma. His last remaining volunteer role was as secretary in a nonprofit organization. He was under pressure to resign because he had not kept good track of its records during his illness. While he agreed that his performance in that position had been erratic, he worried about what it would be like to feel that he had nothing useful to offer. This had in part precipitated his current crisis.

The consultant included among his recommendations a subsequent meeting with Mr. D and supportive friends that would include addressing ways in which he could continue using his knowledge and skills to make a contribution to the lives of others.

AGENCY VERSUS HELPLESSNESS

Agency is the sense that one can make meaningful choices and that one's actions matter. Agency does not imply that a person is in control, which is usually an unrealistic expectation when a person is medically ill. It does imply that a person's choices and actions have influence and make meaningful differences. Agency is often expressed in terms of empowerment or “having a voice.” Antonovsky's research on coping in medical illness found a sense of agency to be an important predictor for good health (

20). Questions for inquiring about a patient's sense of agency include the following:

•.

What is your prioritized list of concerns? What concerns you most? What next most?

•.

What most helps you to stand strong against the challenges of this illness?

•.

What should I know about you as a person that lies beyond your illness? (

21)

•.

How have you kept this illness from taking charge of your entire life? (

21)

An important way to help a patient to regain a sense of personal agency is to assist in rediscovering his or her identity as a competent and effective person. Cassem has emphasized the value of asking seriously ill elderly men, “When were you at the top of your game?” and then fleshing out a rich description of this era of the man's life (

22). The following vignette illustrates how this can be similarly accomplished by helping a person recollect an identity of competence, such as she had been known by her mother:

Ms. E, a 60-year-old woman, had had neurosurgery for a brain glioma 3 days earlier. Psychiatric consultation was requested for her depressed mood. Her initial symptoms had begun a week earlier with incoordination and weakness in her left arm.

“I only have half a brain now,” she told the psychiatric consultant, bursting into tears. The consultant asked what was the hardest thing to bear with this illness. She said she could think that she was moving her left hand, but it in fact would not move. “This has knocked me for a loop,” she said, again weeping.

“Yes, this has thrown you for a loop. It would be that way for most anyone,” the consultant reflected.

Ms. E spoke about guilt she felt while remembering how she had become frustrated with her chronically ill, elderly mother. “Now I know what it was like for her.” The consultant wondered what she now better understood. “I respect her more now,” Ms. E said. “Now I realize how hard it had been for her.”

“If your mother could speak to you about your illness, what do you suppose she would say?” the consultant asked.

“She would say, “Get on with it!”' Ms. E responded. She then remembered the story of two frogs who fell into a farmer's pail of milk. One frog, seeing their predicament, gave up and drowned. The other kept paddling. Soon butter formed and floated to the top. The frog kicked against the butter and hopped out. “I want to be the frog who keeps kicking,” she said.

“Your neurological team wanted us to see you because they were concerned you may be depressed,” the consultant said to her. “We don't think you are depressed. We do think you are as discouraged as anyone would be dealing with something this hard. We won't recommend treatment for depression but do recommend that you get started with physical therapy and rehabilitation. We will come by to see how you are doing.” During the ensuing days, she engaged successfully with her physical therapy, and her mood brightened.

COURAGE VERSUS COWARDICE

Courage is a refusal to be subjugated by fear, even when fear is intensely felt. Witnessing oneself performing even small acts of courage can anchor a sense of self-respect that motivates further courageous acts; likewise, witnessing oneself retreating because of fear can encourage future capitulations. Questions that help patients witness their acts of courage include the following:

•.

Have there been moments when you felt tempted to give up but didn't? How did you make a decision to persevere? (

23)

•.

If you were to see someone else taking such a step even though feeling afraid, would you consider that an act of courage? [If so] Can you imagine viewing yourself as a courageous person? Is that a description of yourself that you would desire?

•.

Can you imagine that others who witness how you cope with this illness might describe you as a courageous person? (

23)

Ms. F was a 35-year-old non-English-speaking Asian woman with recurrent metastatic breast cancer who had a poor prognosis for long-term survival. With her husband interpreting, she told about her fears: that she could not bear more bad news, that she could not bear the pain, and that she could not face going home from the hospital. After she spoke for a time, her husband turned to the psychiatric consultant and said, “I think she is a very courageous woman. She has already been through this twice, and now she may be facing it again. Most people couldn't do what she has done.” The consultant turned to Ms. F and said, “Your husband says you are courageous. Is that how you might describe yourself?” Her demeanor changed as she relaxed and smiled, nodding, “Yes.” The consultant then asked what had helped her to be so courageous during this time. She said that the presence and support of her family members helped her to be strong even when afraid.

Picking up this theme during subsequent inpatient and outpatient meetings, the consultant periodically asked Ms. F either to recollect how she had acted with courage or to notice other occasions when the presence of her family members enabled her to be courageous.

GRATITUDE VERSUS RESENTMENT

Sustaining a capacity for experiencing gratitude rather than resentment or bitterness can help shield against feelings of anxiety or depression. This is particularly so when some good deriving from otherwise tragic events can be acknowledged. Questions that can help locate a sense of gratitude include the following:

•.

For what are you most deeply grateful?

•.

Are there moments when you can still feel joy despite the sorrow you have been through?

•.

If you could look back on this illness from some future time, what would you say that you took from the experience that added to your life? (

21)

The following vignette shows how gratitude can emerge even in the midst of profound suffering (

17).

Mr. G was a 57-year-old man who earlier in the day had asked a friend to bring a gun to the hospital so he could kill himself. He had become distraught after being told that his right leg needed to be amputated because of impending gangrene. This precipitated a request for psychiatric consultation to assess his suicide risk and to determine whether he had the decision-making capacity to refuse surgery.

The consultant explained why he had come: his doctors were worried about his safety, and they wondered as well whether his thinking was clouded by his medications. The consultant asked Mr. G to explain what he understood his doctors to be saying about his condition and what needed to be done medically. Instead of answering the question, Mr. G started telling how hard it is for a man who lives alone to take care of himself—taking care of his yard, getting things out of a cabinet in the kitchen—if he has no leg.

The consultant asked him what he understood to be the alternative if he did not have the surgery. Mr. G said that he would develop gangrene, which would spread and, within a few days, kill him. He would not permit this to happen, so he saw his only choices to be surgery and suicide.

Then Mr. G spontaneously interjected that there was nothing to do but “to go along with what they said.” The consultant recalled that moments earlier he had been thinking that it would be better not to live. The consultant asked what had been the turn in his thinking. “I had prayed like hell. I asked God to take it away. But he didn't.” The consultant asked whether Mr. G sensed what God would want him to do now.

“He wouldn't want me to kill myself,” Mr. G responded.

“What do you think God understands about your situation?” the consultant asked.

“He knows I've done the best I could,” Mr. G said, beginning to weep.

“Is it that you feel you know what God would want you to do, but it is hard to understand what he has in mind—and it is hard to feel trusting toward God, even if you are going to do what you know he wants you to do?” the consultant asked.

Mr. G nodded.

The consultant then asked who were other important people who would be with him in his suffering and whom he could count on to support him. “My ex-wife has been calling me,” he responded, weeping. She had told him that she loved him and wanted him to have the surgery. He also told about telephone calls from his children encouraging him to have the surgery. He expressed appreciation for his doctor, whom he felt had stood by him patiently. Mr. G then consented to the amputation and proceeded with rehabilitation uneventfully.

CONCLUSION

Demoralization in medically ill patients can be usefully regarded as the compilation of different existential postures that position a patient to retreat from the challenges of illness. For most humans, illness touches on multiple existential themes, some of which are more pressing than others. For one person, helplessness may dominate, despair for another, and meaninglessness for yet another. When different existential postures blend together, they give rise to a sense of subjective incompetence that has been regarded as a distinguishing feature of demoralization (

1,

3,

24).

In bedside interviews with patients, a fruitful strategy is first to discern which existential postures most dominate the patient's experience of illness, then to focus further questions and interventions toward those themes. Interviewing methods that aim to mobilize specific existential postures of resilience are built on the witnessing, validating, and normalizing of a patient's personal experience of illness (

2,

5–

8). This must be underscored, since resilience-building questions asked prematurely fall flat, regarded as naive efforts to solve tragic problems that are insolvable. The root meaning of “compassion”—“to suffer with”—is key, in that a patient must first know that a clinician can understand and is willing to feel together the suffering, before opening to the intimacy of such a question as, “During the worst of times, from where do you draw hope?”

Bedside psychotherapy has long challenged consultation-liaison psychiatrists because of limitations on privacy, patients' preoccupations with biomedical concerns, and the fact that attending physicians and not patients usually request psychiatric consultations. Its role has been curtailed by managed mental health care, which further shifted the focus of consultation-liaison psychiatry toward diagnostic questions and medication-based management of psychiatric emergencies. However, the need for effective interventions that can restore morale in medically ill patients calls for a renewed focus on bedside psychotherapy in the consultation-liaison training of psychiatrists.