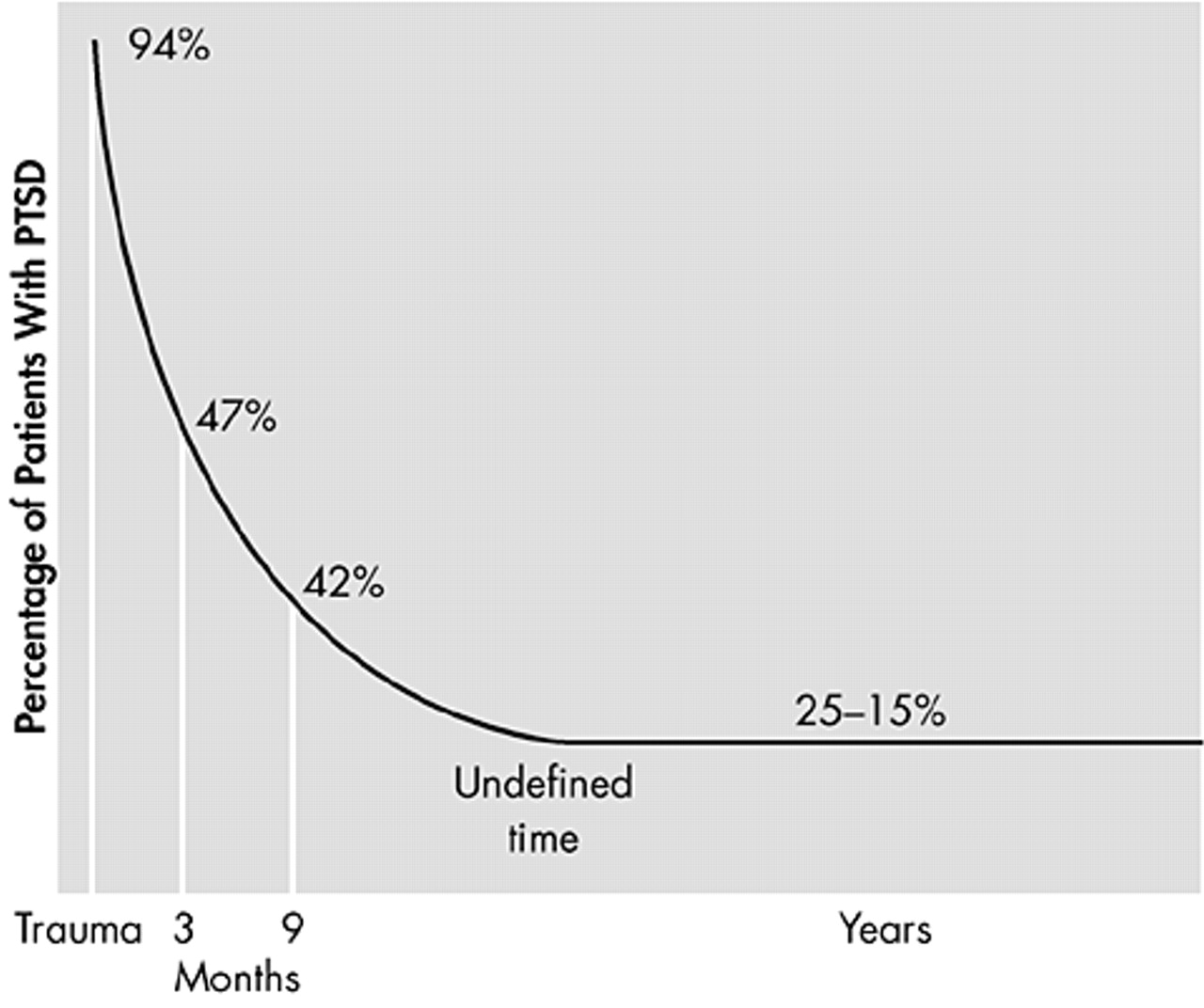

Appropriate treatment of PTSD is essential to reduce symptoms and increase both the functioning and quality of life of the patient. Early intervention is particularly crucial in order to help prevent the development of secondary chronic morbidity.

There are five main treatment goals when treating PTSD: reducing the core symptoms, improving stress resilience, improving quality of life, reducing disability and reducing comorbidity.

A number of treatment outcome studies for PTSD have focused on cognitive-behavioral therapy programs, which include variants of exposure therapy, anxiety management and cognitive therapy. More recently, eye movement and desensitization therapy has been employed. Pharmacological treatments are being studied. Both kinds of treatment are effective.

Psychosocial treatment

Psychosocial treatment of PTSD has shown some promising results and, when effective, has been associated with low relapse rates. Of the existing treatments, exposure therapy has the strongest evidence of efficacy in different populations of trauma victims with PTSD. However, a minority of patients failed to show sufficient gains with this therapy.

43 Anxiety management techniques have also been shown to be effective in the treatment of PTSD after rape,

11 although not widely studied. Cognitive therapy has also been seen to be effective in rape victims.

44 More recently, a study by Marks et al.,

45 of different victim populations with a history of PTSD of at least 6 months' duration studied the treatment effect of prolonged exposure (imaginal and live) alone; cognitive restructuring alone; combined prolonged exposure and cognitive restructuring; or relaxation without prolonged exposure or cognitive restructuring. The study showed that both prolonged exposure and cognitive restructuring were each therapeutic on their own, were not mutually enhancing when combined, and were each superior to relaxation.

Interestingly, this lack of advantage for combining different types of psychosocial treatments was also found in a study by Foa et al.

46 Studies attempting to examine augmentation of exposure therapy outcome with the addition of cognitive restructuring do not show any additional benefit over exposure therapy alone. No studies have examined the relative efficacy of pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, and whether combination of the two will augment the efficacy of each.

Eye movement and desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) is a relatively new therapy for PTSD that consists of a form of exposure accompanied by saccadic eye movements.

47 In EMDR, the therapist asks the patient to visualize images about the trauma, while inducing eye movements by asking the patient to track rapid side-to-side movement of the therapist's finger. A cognitive therapy component is also included by asking patients to replace negative thoughts with positive ones. There have been several studies of the efficacy of EMDR in the treatment of PTSD,

46–49 although most have not been well controlled.

43 A well-designed study

49 found EMDR was inferior to prolonged exposure cognitive therapy.

Successful treatment of PTSD with regard to the patient will involve attitude to treatment, capacity to tolerate distress, availability of support, and extent of comorbidity.

50 To determine the real benefit of psychosocial treatments for PTSD, further large, well-controlled studies that compare the benefits of specific techniques are required.

Pharmacotherapy

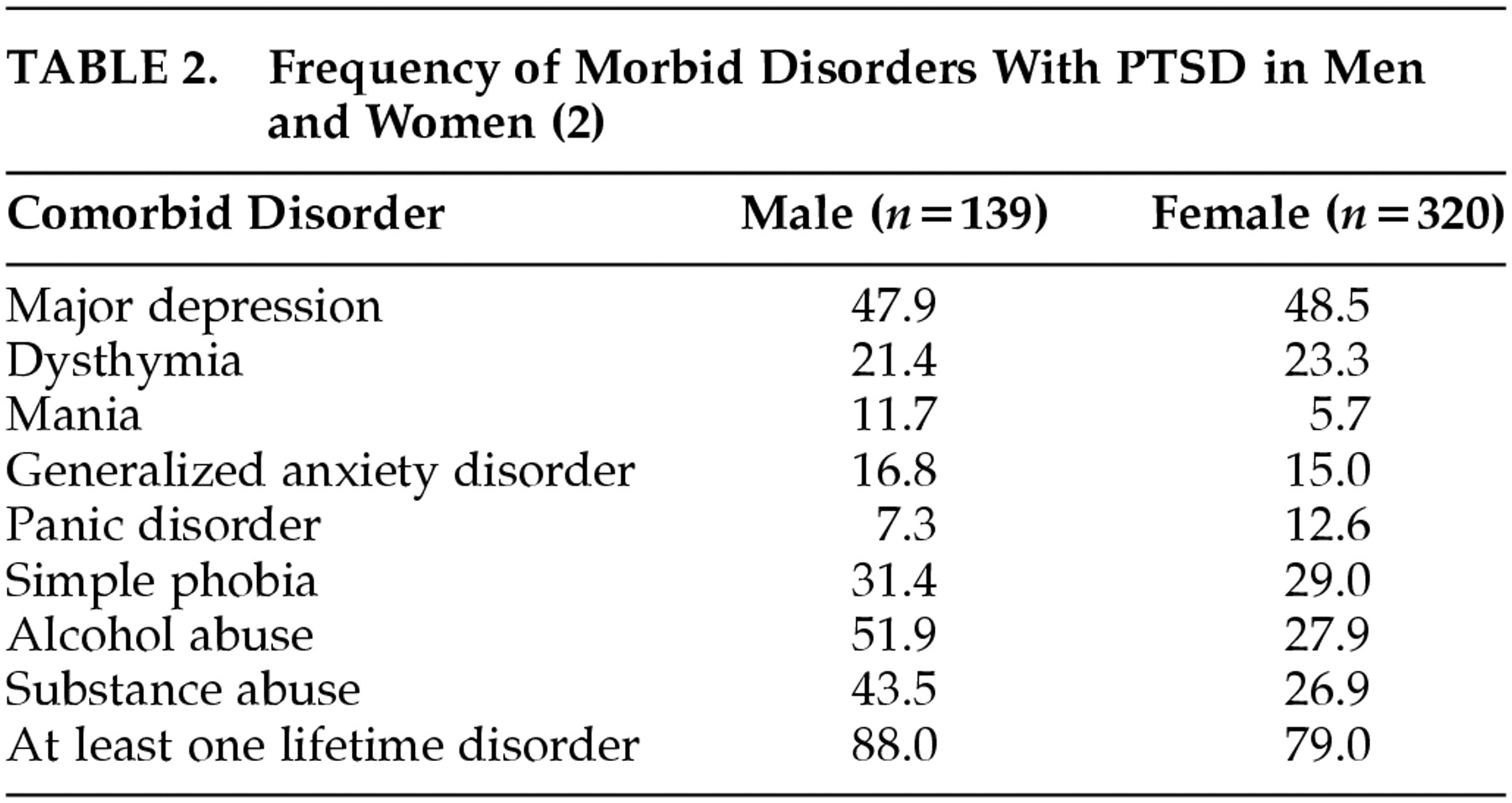

The principal goals of pharmacotherapy are reducing PTSD symptoms, improving resilience to stress and quality of life, and reducing disability and comorbidity. Reducing comorbidity is particularly important since patients rarely present with pure PTSD. There are three main classes of drugs that have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of PTSD: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as amitriptyline and imipramine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as phenelzine, and SSRIs such as sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine. In addition, a variety of other drugs show promise including antiadrenergics, anticonvulsants and antidepressants (lamotrigine, nefazodone, clonidine).

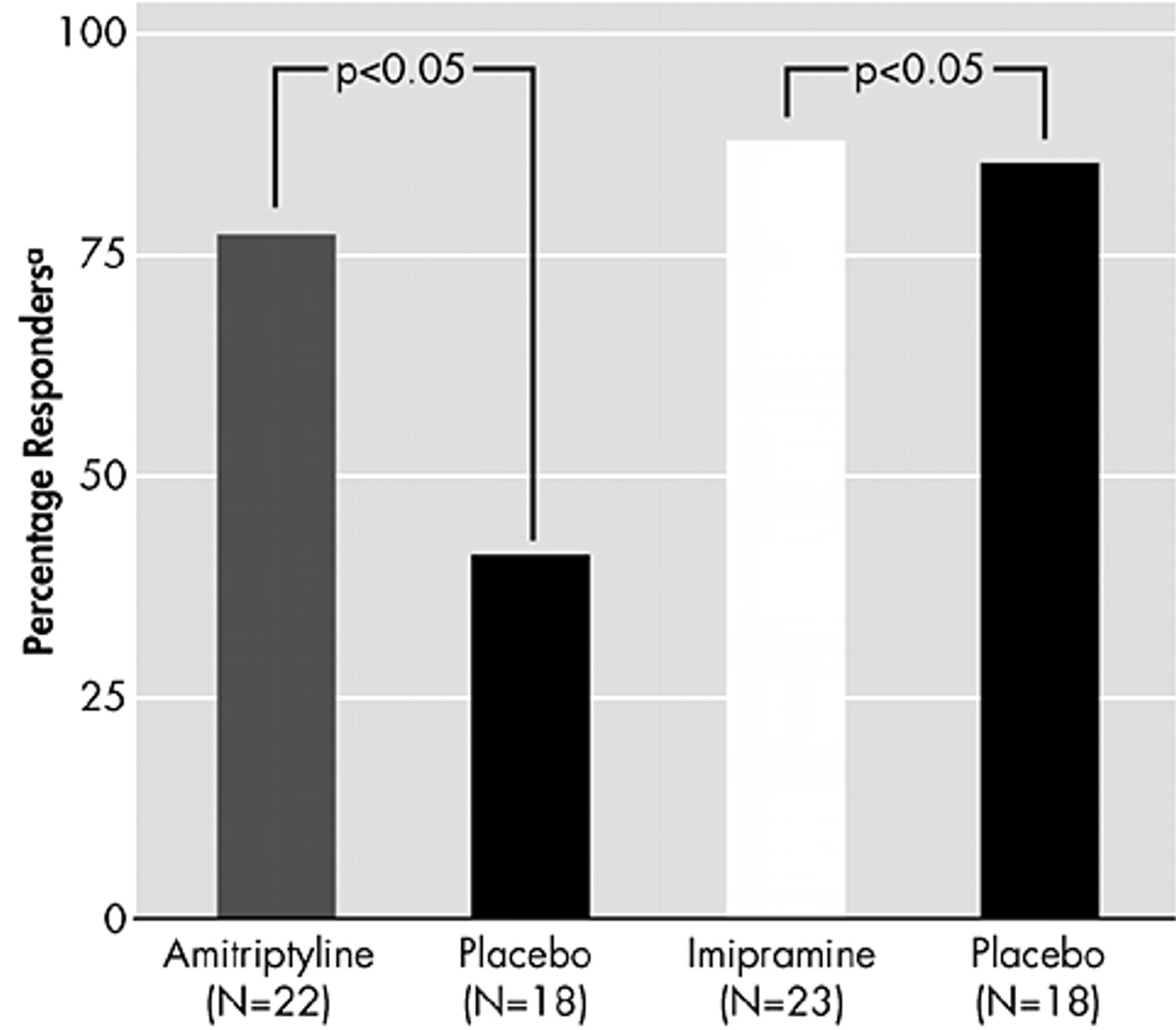

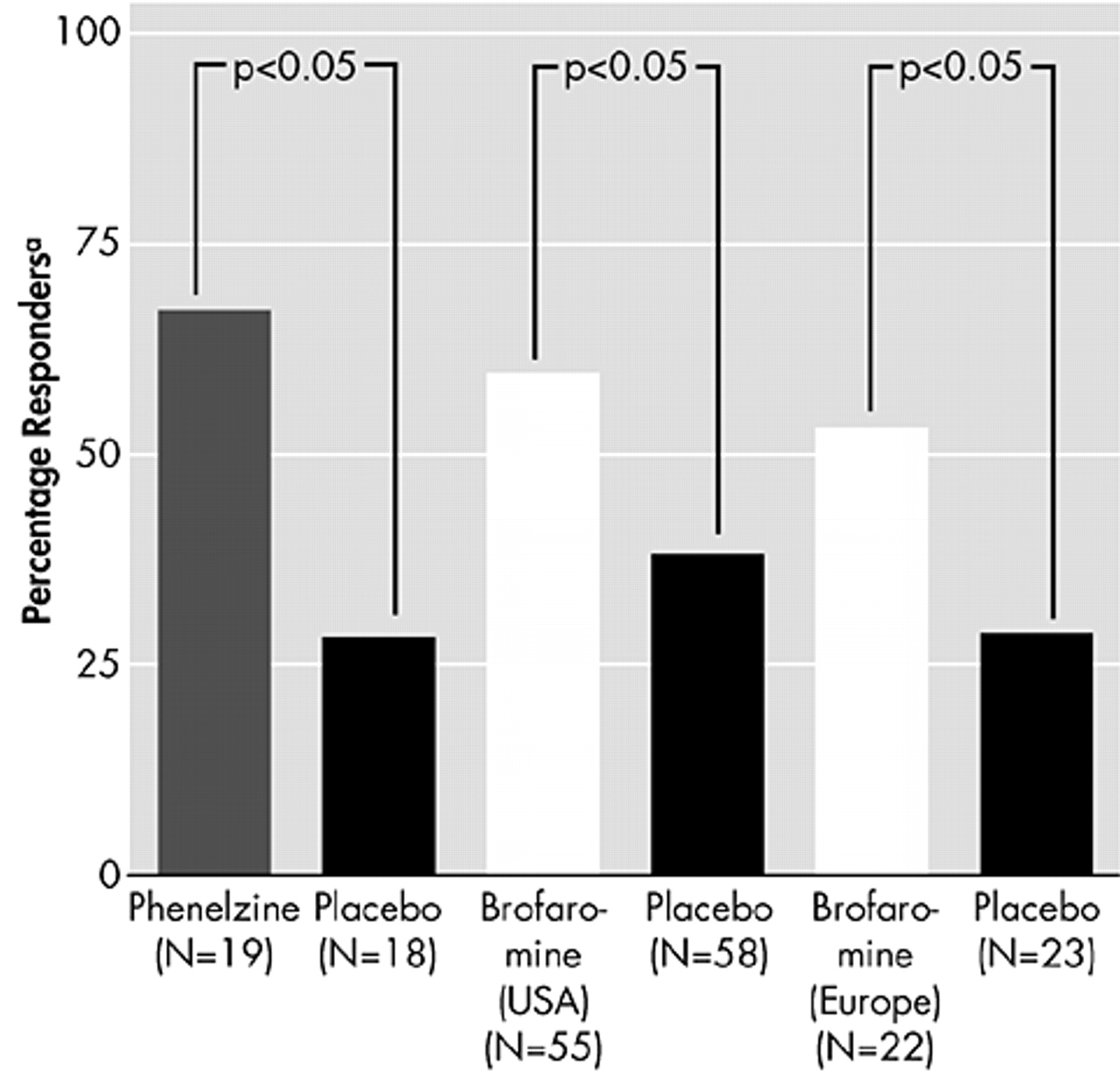

There is considerable evidence from placebo-controlled trials that TCAs and MAOIs are effective in reducing symptoms of PTSD (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

51–53 There is also preliminary evidence from open-label studies of carbamazepine, valproic acid, and from a small double-blind trial of lamotrigine, that anticonvulsants can produce benefit in PTSD.

54–56More recently, placebo-controlled studies have shown that the SSRIs sertraline

57 and paroxetine

58 are effective in decreasing symptoms of PTSD, and considerable interest has centered on these new data. Similarly, there have been positive placebo-controlled trials for fluoxetine, however results in USA combat veterans

59,60 were not as positive as for the general PTSD population.

24 A European study found benefit for fluoxetine in predominantly combat veterans, with relapse prevention effects in maintenance treatment.

61,62In the 12-week, double-blind study of sertraline in 187 psychiatric outpatients with DSM-III-R PTSD, sertraline treatment yielded a significantly greater improvement than placebo in mean change from baseline for Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale Part 2 (CAPS-2) total score (

P=0.02).

57 In addition, sertraline was significantly better than placebo for the symptom clusters avoidance/numbing (

P=0.02) and arousal (

P=0.03), but not on reexperiencing/intrusion (

P=0.14). In this study, however, 73% of the population was female and 61.5% had suffered physical or sexual assault. Further studies of sertraline are required to demonstrate its efficacy in both genders and across all trauma types. A relapse-prevention study found the risk of relapse to be significantly less with sertraline than with placebo after 9 months of treatment.

63In a 5-week double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in 64 patients (22 women and 42 men) (31 veteran and 33 nonveterans), fluoxetine significantly reduced overall PTSD symptomatology as assessed by total CAPS score.

59 However, the difference in PTSD symptom reduction occurred primarily in the subscales “numbing” (for the nonveteran group) and “arousal.” Fluoxetine was an effective antidepressant in the total sample as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). However, these improvements in depression did not predict improvement in PTSD score. While there was substantial improvement in depression (HAM-D) in the veteran sample (

P= 0.005), there were no meaningful changes in numbing symptoms (

P=0.70). Conversely, the nonveteran sample had a modest improvement in depression (HAM-D,

P=0.04), but there was a substantial improvement in numbing (

P=0.002). In general, nonveteran patients responded much better than veteran patients, which is probably reflective of the higher level of symptomatology in the veterans. In another double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in 53 civilians over a 12-week period, fluoxetine (up to 60 mg/day) significantly reduced overall PTSD symptomatology as assessed by the Duke Global Severity Rating for PTSD, the Structured Interview for PTSD, and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS).

24 Vulnerability to the effects of stress also responded well to fluoxetine.

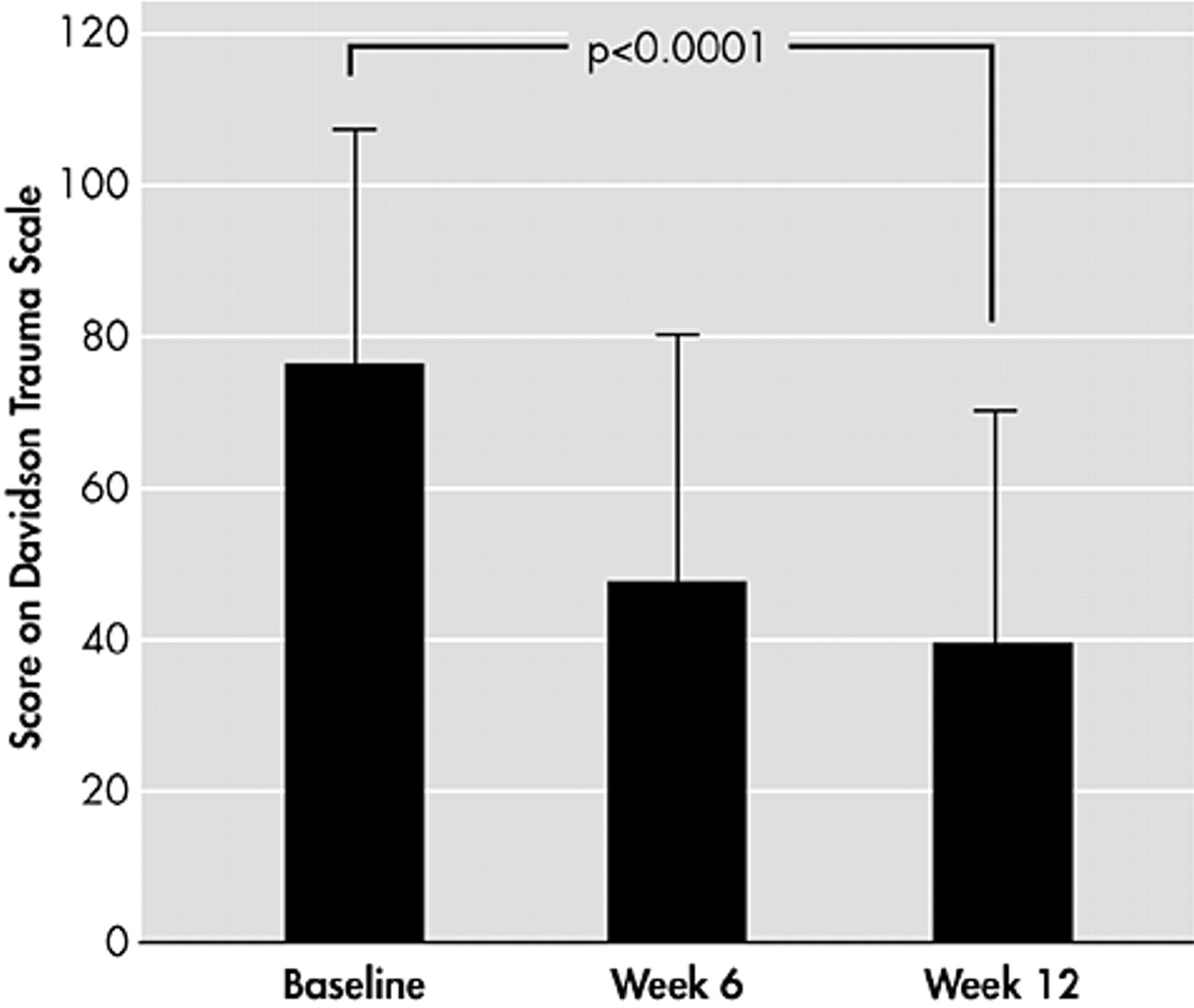

In the 12-week, open-label study with paroxetine that was conducted in 19 civilians with DSM-III-R PTSD,

64 patients showed significantly reduced mean PTSD symptom scores for both the DTS score (

P<0.0001) (

Figure 9) and the Impact of Event Scale score (

P<0.0001). In addition, there were significant improvements in all symptom clusters for both scales. Interestingly, cumulative childhood trauma scores were significantly and negatively correlated with treatment response on the total DTS score (

r=0.52,

P<0.03). Since the study by Marshall, there has been a series of large clinical trials with paroxetine in PTSD. The clinical program involved 1180 patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD, and demonstrated that paroxetine relieves the symptoms of PTSD, significantly reducing mean change from baseline in CAPS-2 total score and Clinical Global Impression global improvement scale. In addition, it significantly reduced the CAPS-2 score for reexperiencing/intrusion (

P<0.001), avoidance/numbing (

P<0.001), and arousal (

P<0.001) compared with placebo. This new data, which was generated in 12-week, double-blind, randomized, fixed- or flexible-dose studies also confirmed that treatment benefit with paroxetine (20–50 mg/day) was observed across all trauma types and in both genders.

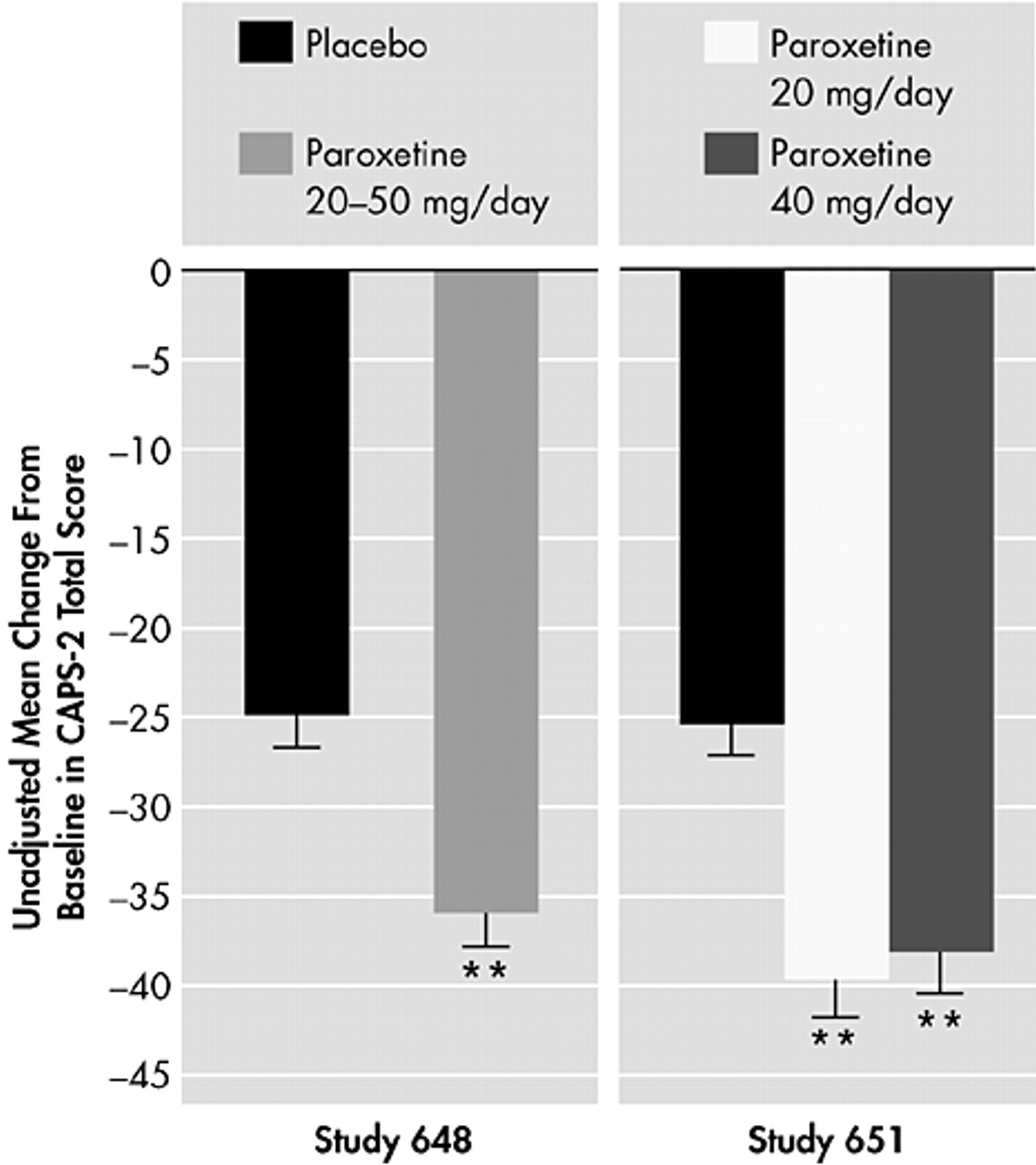

65,66In the fixed-dose study, which was conducted in the United States with 551 PTSD patients who had experienced traumas, including physical or sexual assault, witnessing an accident, experiencing a serious accident/fire/injury, being in war/combat or being involved in a natural disaster, paroxetine was given in doses of either 20 mg or 40 mg/day.

58,66 Decreases from baseline in CAPS-2 total score were significantly greater (

P<0.001) for both doses compared with placebo (

Figure 10). In addition, decreases from baseline in the 8-Item Treatment Outcome PTSD Scale (TOP-8) total score and DTS total score were also significant for both doses (

P<0.001). Similarly, in the U.S. flexible-dose study in which 307 patients received 20–50 mg/day of paroxetine, there were significant decreases from baseline for CAPS-2 total score (

P<0.001) (

Figure 10), TOP-8 total score (

P<0.001), and DTS total score (

P<0.001).

58,65Paroxetine was well tolerated with an adverse event profile similar to that in other anxiety indications.