RESULTS

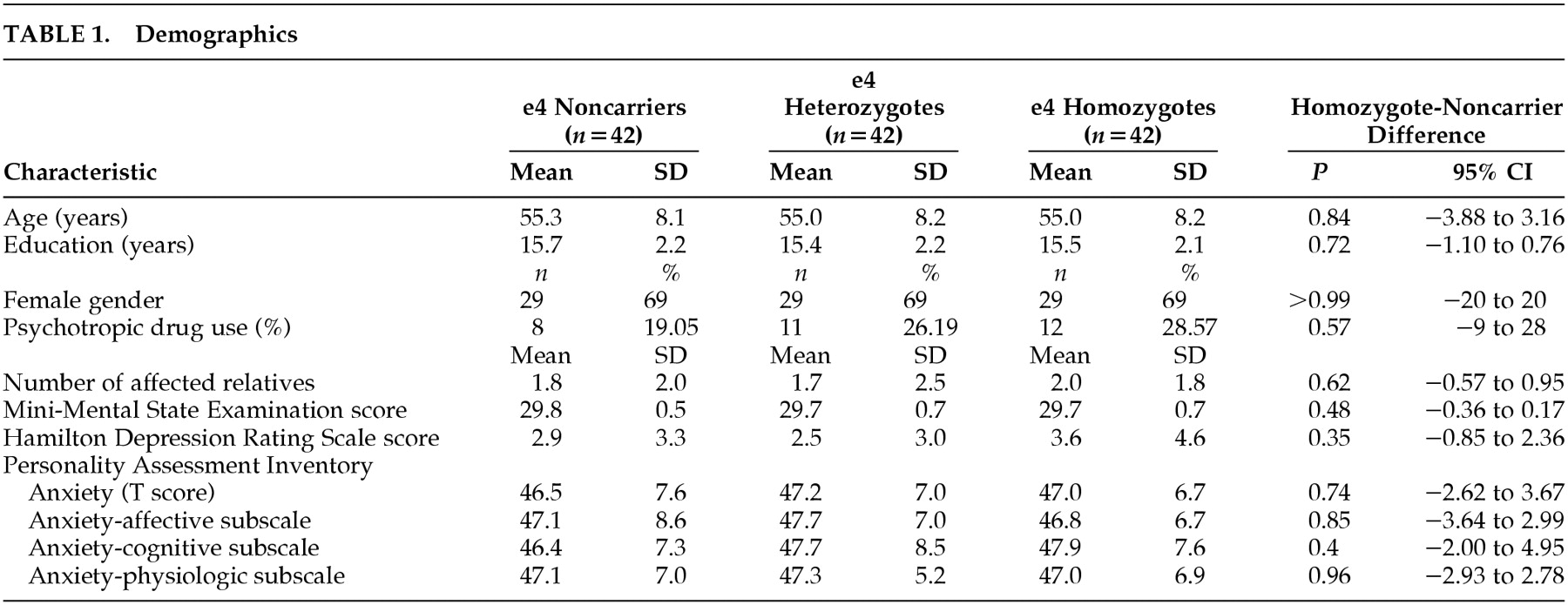

The demographic data are summarized in

Table 1. Each of the three genetic groups had 42 members and were very closely matched on all demographic variables as well as on the Folstein MMSE and Hamilton Depression Scale (

Table 1). Overall, the use of psychotropic medications was 24.6% including 28.6% of the HMZ, 26.2% of the HTZ, and 19.0% of the NC (

P=0.57 for all three groups, and

P=0.31 for HMZ and NC groups). This was almost entirely related to the use of antidepressant medications which were prescribed for mild depression, fibromyalgia, and sleep. Four participants were taking a benzodiazepine (three HTZ and one HMZ) as a sleeping pill in all cases.

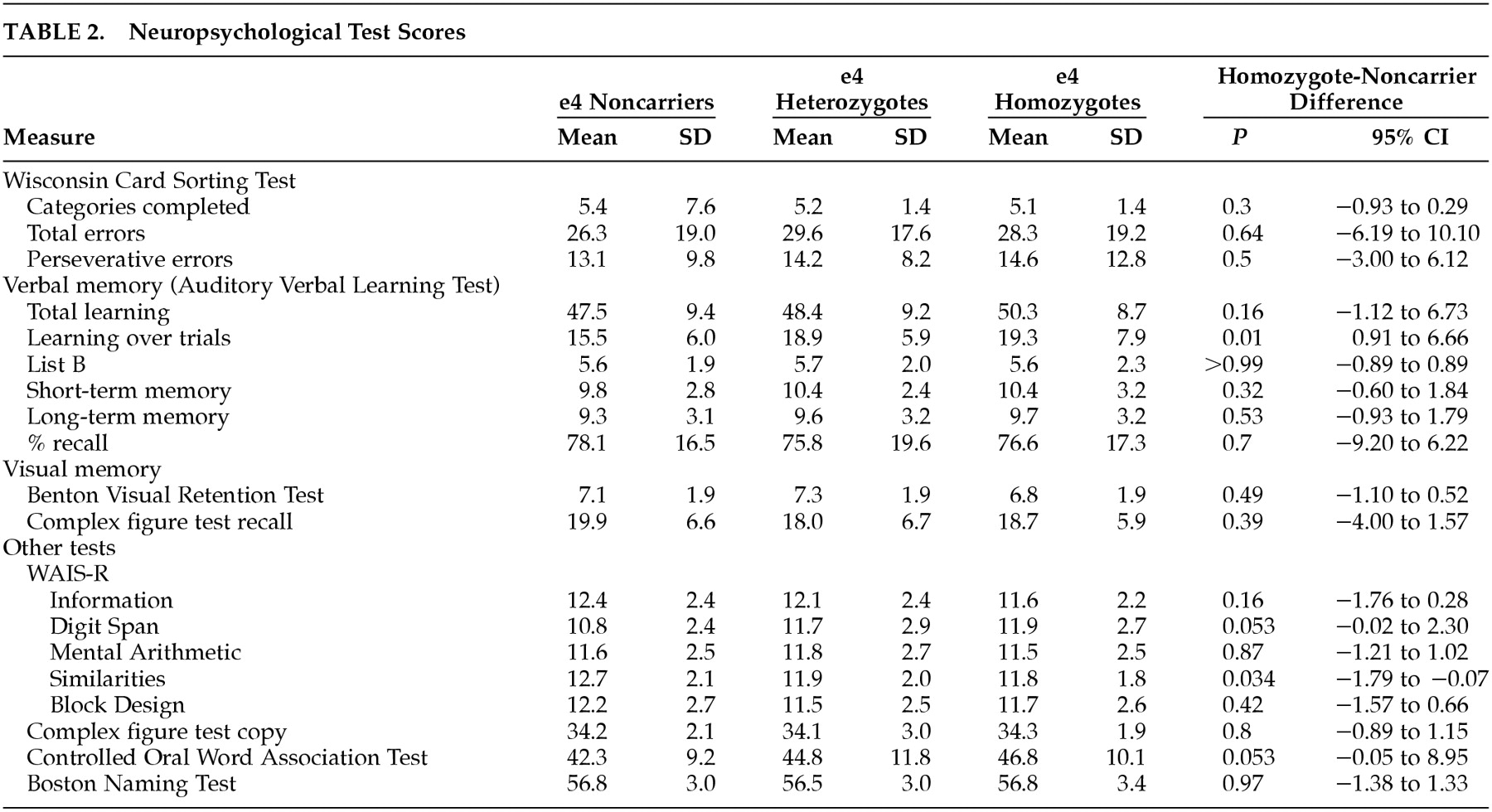

Table 2 summarizes the neuropsychological test scores. The HMZ had the highest mean Total Learning, Learning Over Trials (LOT), and Long Term Memory (LTM) scores on the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) further emphasizing the normality of their memory skills. Mean scores for the HMZ group were significantly higher than NC on AVLT LOT (

P=0.01), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Span (

P=0.053) and the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (

P=0.053). Mean scores for the HMZ group were significantly lower than NC on WAIS-R similarities (

P=0.034), but the mean score was still within less than one point of the NC and still well above the normative average of this test. There were no significant differences between the three genetic groups on any of the three WCST test measures, or on T-scores of PAI-Csc-ANX or its three subscales. When neuropsychological test scores were adjusted for PAI-Csc-ANX, the results did not change. Comparing neuropsychological test scores between psychotropic drug users and nonusers showed minimal differences overall, and none on the WCST. Drug users had significantly lower scores than nonusers on the AVLT LTM (mean=8.39, SD=3.07, versus mean=9.87, SD=3.07) (

P=0.021) and Percent Retention (PR) (mean=69.32, SD=18.66, versus mean=79.31, SD=16.80) (

P=0.006). When the drug users and nonusers were subdivided by APOE genotype, the NC showed no significant differences between drug users and nonusers on any measure, but the HMZ did on AVLT LTM (

P=0.011), PR (

P=0.049), and on WAIS-R Information (

P=0.017).

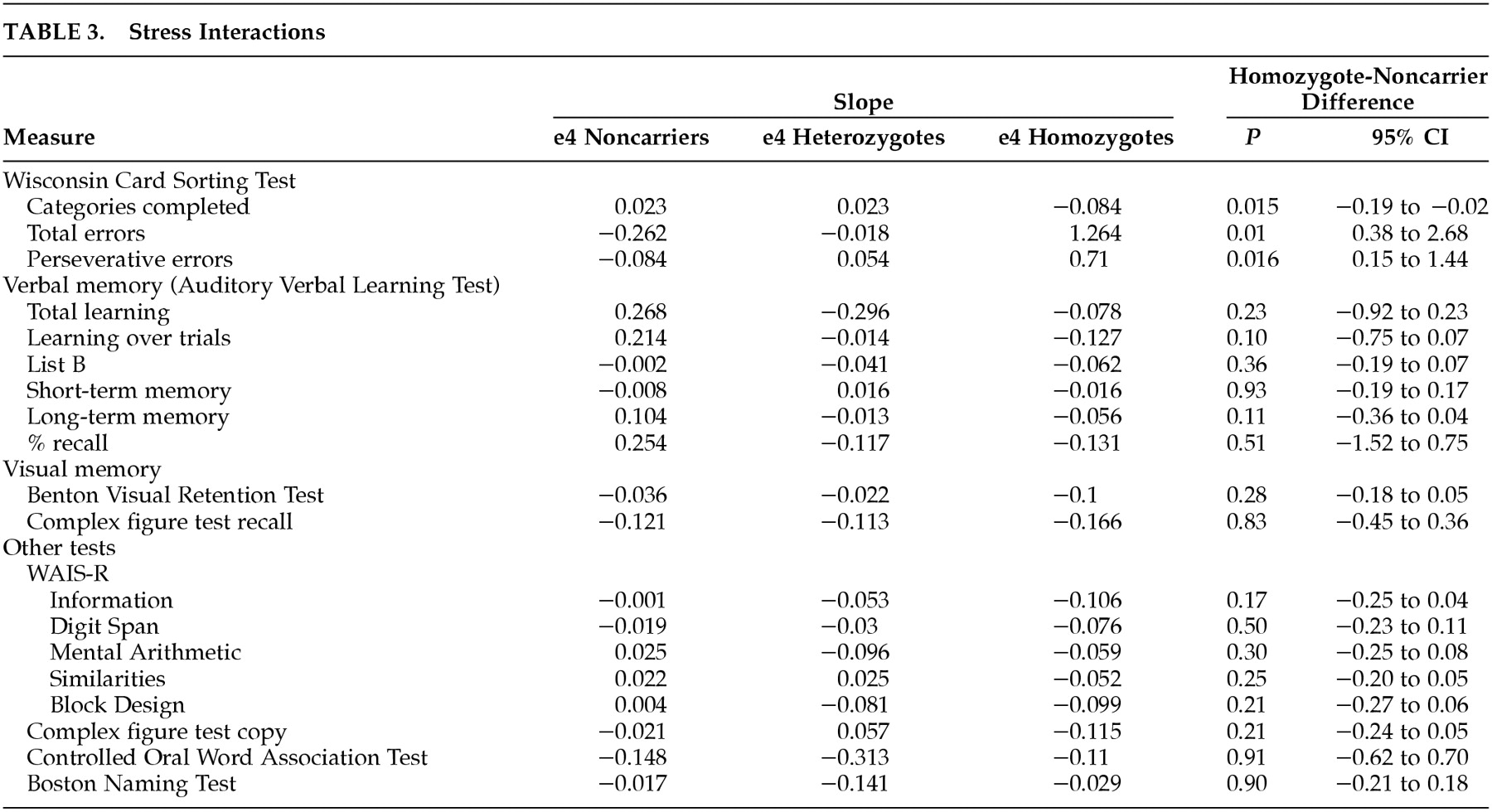

Table 3 shows the slope of the linear relationship between each neuropsychological measure and PAI-Csc-ANX, and compares the slopes between APOE e4 HMZ and NC. Anxiety had an adverse impact on cognitive performance in all three genetic groups. Judging purely from the slopes, of 19 measures, HMZ performed worse with increased anxiety on all 19, HTZ on 14, and NC on 9. For the WCST scores, the slopes indicate that the HMZ performed worse with increased anxiety on all three measures. They completed fewer categories (β=−0.84), made more total errors (β=1.264), and made more perseverative errors (β=0.710). The absolute slope magnitude for the other genetic subgroups on each of these measures was considerably lower indicating much less of an effect, and generally did not indicate a poorer performance on the WCST. Comparing the slopes of the lines for the HMZ and NC groups, the HMZ declined significantly more steeply with increasing PAI-Csc-ANX score on all three WCST measures: category (

P=0.015) (

Figure 1), total errors (

P=0.010) (

Figure 2), and perseverative errors (

P=0.016) (

Figure 3).

Figures 1,

2, and

3 depict these relationships graphically. Comparing the HTZ and NC groups showed no significant differences in slope for WCST categories (

P=0.99), total errors (

P=0.66), or perseverative errors (

P=0.66). When age was added as a covariate, the results did not change. Psychiatric drug use was added to the WCST-ANX interaction model, and it was found that the results were not affected. The psychiatric drug use was inconsequential to the WCST scores-anxiety interaction model.

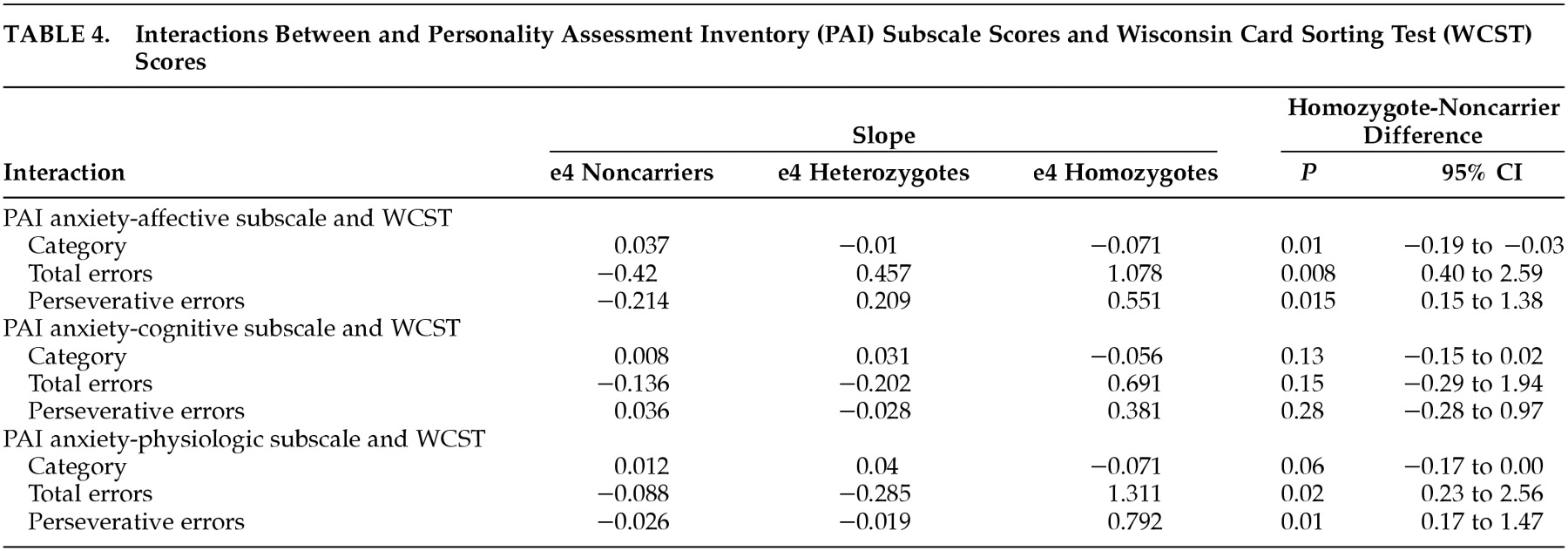

Table 4 shows the interaction of each of the three PAI anxiety subscales (ANX-C, ANX-A, and ANX-P) with each of the three WCST scores. Examination of the interaction using the ANX-C scale failed to find a significant relationship between cognitive anxiety and any aspect of WCST performance in either the HMZ or NC group. All three of these WCST performance variables were inversely related to the ANX-A scale in the HMZ group, suggesting the affective component of anxiety interfered with all three measures of problem-solving performance in the HMZ group. When the ANX-P subscale was examined, there were significant interactions with WCST total errors and WCST perseverative errors in the HMZ group. Higher anxiety scores were related to more errors and more perseverative errors. The slopes of the regression lines were not significantly different for number of WCST categories learned. These findings suggest that total anxiety, the affective component of anxiety and the physiological component of anxiety interfere with problem-solving ability in the HMZ group. They do not interfere in the NC group. The cognitive component of anxiety, which includes excessive worrying and concern, did not interfere with WCST performance in either group. Judging only from the slopes, the HMZ were adversely affected in all nine interactions, the HTZ in three (all the ANX-A subscale interactions), and the NC in only one (ANX-C subscale-WCST Perseverative Error interaction).

DISCUSSION

Our results are consistent with the observation that anxiety adversely affects cognition. More specifically, however, in this study we found a significant negative relationship between a trait measure of anxiety and measures of problem solving in APOE-e4 HMZ, but not in NC. The slopes of the relationship between PAI ANX and three WCST measures were all indicative of a poorer performance for HMZ, whereas only one measure was in the direction (slightly) of a more negative performance in the HTZ group, and none was in the NC group. Comparing the slopes of the correlations between HMZ and NC groups, all three WCST measures reached statistical significance showing significantly greater decline in performance in the HMZ group than in the NC group. Before our results can be interpreted, limitations and strengths of our study should be discussed.

An important limitation of this study is the possibility of type I errors. This is an exploratory study involving multiple comparisons whose findings need to be confirmed in an independent sample. Still, the consistency of our results across all WCST measures and the PAI ANX subscores suggests this may not explain our findings. A second important limitation regards the specific focus on chronic or trait anxiety, rather than acute or state anxiety. While trait anxiety is a valid topic for research, our study does not yet determine how a person's state of anxiety at the time of neuropsychological testing is related to cognitive performance. A third limitation is the potential confounding effect of psychotropic medication, particularly antidepressant medication use. Comparing scores on neuropsychological measures between users and nonusers however showed minimal differences overall, and none on the WCST. Nonetheless there were significant differences between drug users and nonusers on a measure of delayed verbal memory, and this seemed driven by a differential effect of drug use on APOE e4 HMZ. This is consistent with our hypothesis that APOE e4 HMZ don’t perform as well under conditions of physical or psychological stress than NC, but does not account for the effect on anxiety on overall test performance in this study or the more specific effects of anxiety on the WCST. Finally, some might regard the WCST itself as a limitation. The different scores generated by the WCST are themselves highly correlated (absolute R values between the three measures in this cohort ranged from 0.801 to 0.893) so that poor performance on one will correlate with a poor performance on another. The correlation of the WCST with prefrontal function (though widely used for that purpose) is not absolute.

29–33 However, the test design is suitable for the intention of this study because it requires patients to infer a solution based on the success or failure of their own performances.

This study capitalizes on the inclusion of a large number of cognitively normal APOE e4 HMZ, an uncommon genotype that occurs in only about 2% of the population.

34 Furthermore, it capitalizes on very close matching of APOE e4 HMZ groups with HTZ and NC groups by age, gender, education, and family history of dementia in at least one first degree relative. Finally, it capitalizes on the neuropsychological documentation of cognitive normality of our study sample assuring as closely as possible, that the findings reported are truly preclinical, and not early stage symptomatic AD.

Regarding the PAI ANX subscales, all had a negative influence on WCST performance, including the ANX-C subscale even though the ANX-C subscale failed to reach statistical significance by itself. The differences between the subscales may be more minor than the p values otherwise imply, but suggest that the affective and physiologic components of anxiety, more than worry, disturb problem solving.

Was the relationship between anxiety and cognition for the APOE e4 HMZ specific to problem solving? Anxiety adversely affected a wide variety of cognitive skills in all three subgroups, though the effects were generally most severe and most consistent in the HMZ group. Only the problem solving measures related to the WCST however were significantly different between HMZ and NC groups. Overall, the slope of the correlation between PAI ANX and the three WCST measures were all indicative of a poorer performance for HMZ. Only one measure was in the direction (slightly) of a more negative performance in the HTZ group, and none was in the NC group. Comparing the slopes of the PAI-WCST correlations between HMZ and NC groups, all three WCST measures reached statistical significance showing significantly greater decline in performance in the HMZ than NC (

Table 3). The baseline differences in mean neuropsychological test scores between the HMZ and NC groups listed in

Table 2 were minor, and did not suggest a specific pattern. Three test scores that were below or near the 0.05 significance level were the AVLT LOT, WAIS-R digit span and similarities, and the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (

Table 2). Because the HMZ actually did better than NC on three out of four of these tests (including WAIS-R Digit Span, another prefrontally sensitive test), it does not appear that baseline impairment in the HMZ could explain our results. Rather, our data show that chronic anxiety has a more negative impact on cognitive skills that are otherwise better preserved in APOE e4 HMZ than in NC, particularly regarding problem solving.

This study suggests that the effect of chronic anxiety on cognition, and particularly problem solving, may be influenced by APOE genotype. This has several potential clinical implications, each of which leads to a readily testable hypothesis. First, in the immediate “presymptomatic” period of very early stage AD, while affected individuals may still be employed or otherwise normally engaged in the “business of everyday life,” problem solving may be impaired in professional activities or activities of daily living, especially brought on during periods of greater stress. Indeed, it has been shown that frontal lobe function (including performance on the WCST) can decline in early stage AD,

35,36 and stressful or demanding situations such as holiday gatherings and travel often exacerbate functional impairments. The second implication regards the effect of such anxiety-induced problem solving difficulty on neuropsychological testing. It may be that individuals at the highest risk for AD, or in very early stages, may have disproportionately greater difficulty, and impaired performances attributed to “being nervous” should perhaps be viewed with heightened diagnostic suspicion.

Why should APOE genotype influence the effect of anxiety on problem solving in contrast to other cognitive skills which appear to be more equally affected across genetic subgroups? One possibility is that this reflects reduced prefrontal capacity under stressful conditions. Anxiety places greater functional demand on prefrontal cortices.

37 We have previously shown radiological

10 and neuropsychological

11,12 evidence that prefrontal cortical functional decline is not only age-sensitive, but is particularly so in APOE e4 HMZ. Despite the normal performances on a wide variety of neuropsychological tests in a low stress, well rested baseline setting, APOE e4 HMZ may have less “reserve” under conditions of physical and emotional stress. If so, it would seem likely the areas of greatest susceptibility will be those for which preclinical evidence of declining function exists.

A second possibility is that there was a higher proportion of undiagnosed anxiety disorders in the APOE-e4 HMZ group. Our groups, however, were very well matched in terms of Hamilton Depression Scale, and there were no patients enrolled who carried a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or panic disorder making this explanation less likely in our study.

Another possibility could be a differential neuro-humoral response to stressful states possibly reflecting the role of APOE in steroidogenesis,

38,39 and the role of steroid hormones in brain physiology and neurodegeneration. Anxiety and other forms of physiological and psychological stressors may be associated with certain hormonal and neurochemical changes, including elevations in plasma cortisol levels.

40–42 Cortisol binds to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors in hippocampal neurons and other brain regions, causing an alteration of calcium flux and glutamate uptake which may impair the ability of these neurons to withstand various metabolic stressors (the glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis of neurodegeneration

43). Similarly, depression is another significant physiological stressor which affects the adrenocortical axis, may contribute to cumulative AD susceptibility,

44 and may occur with increased frequency during the “preclinical” stage of AD.

45 Accumulating clinical data suggest that glucocorticoids are relevant for human brain function in addition to age-related neurodegeneration.

46–49 Peskind et al.

50 have recently shown that cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of cortisol in patients with AD are highest in APOE e4 HMZ, and another logical extension of our findings will be to correlate basal plasma cortisol levels with APOE genotype in this cohort.

Our findings are consistent with the known gene dose effect of e4 on AD susceptibility. For all neuropsychological measures, the number of adverse interactions with PAI ANX was proportional to e4 gene dose. When the PAI anxiety subscale interactions with the WCST measures were analyzed, again, the number of adverse interactions was proportional to e4 gene dose. Similarly, we have previously reported preclinical metabolic changes using resting [

18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans in APOE e4 HMZ

10 that were more severe than in APOE e4 HTZ

51 (both groups were compared to an APOE e4 NC group). Because of the rigor used to insure a cognitively normal sample, these changes are truly preclinical and not simply an early symptomatic stage.

In summary, we have found that there is a distinctive association between chronic anxiety and poorer problem solving performance in cognitively normal APOE e4 HMZ. These findings should be considered exploratory, need to be confirmed in an independent sample, and should be extended to determine how the acute anxiety state might differentially impair problem solving in persons at genetic risk for AD. Our data raise a number of testable hypotheses that collectively may provide further insight into important clinical challenges and neurodegenerative mechanisms related to aging and AD.