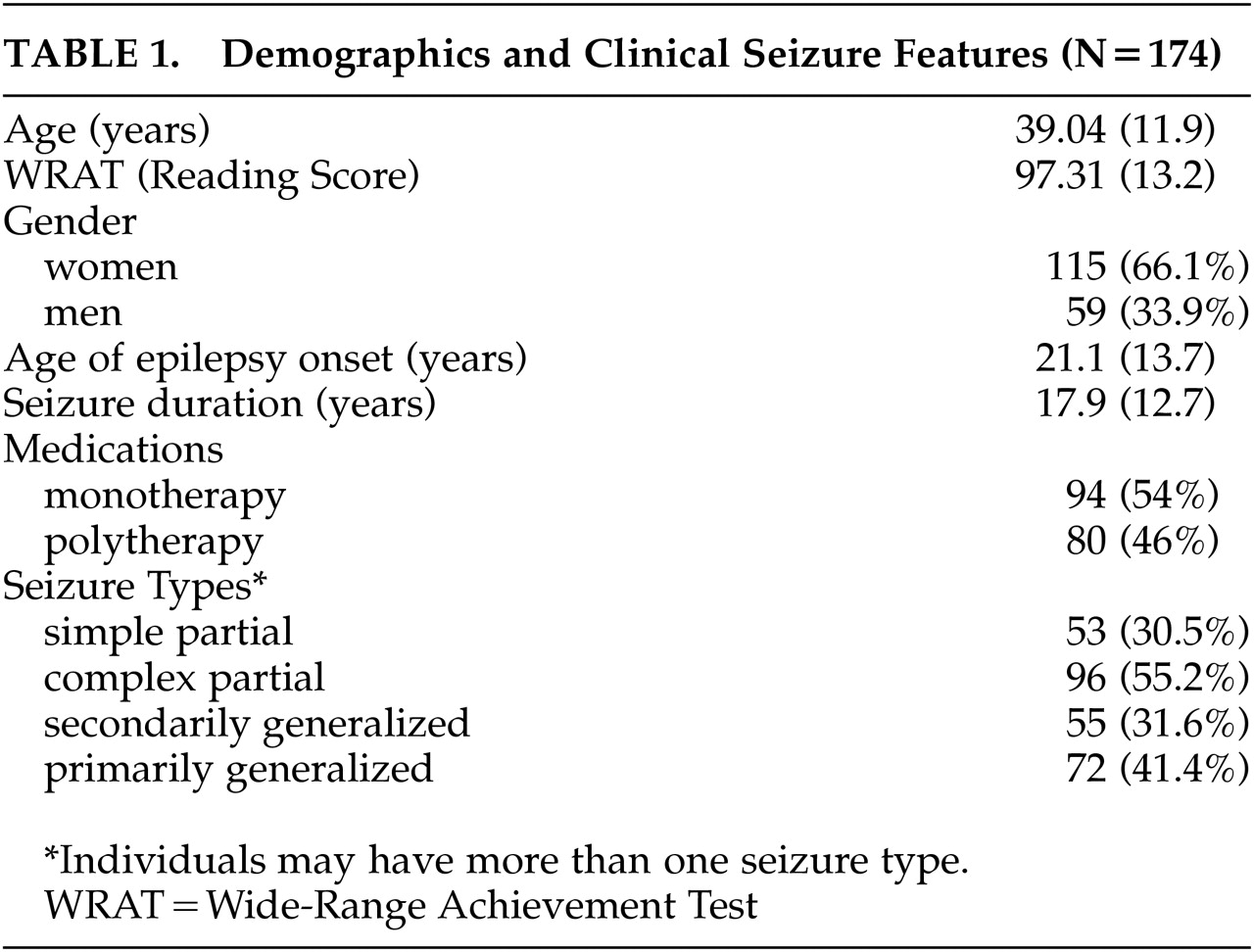

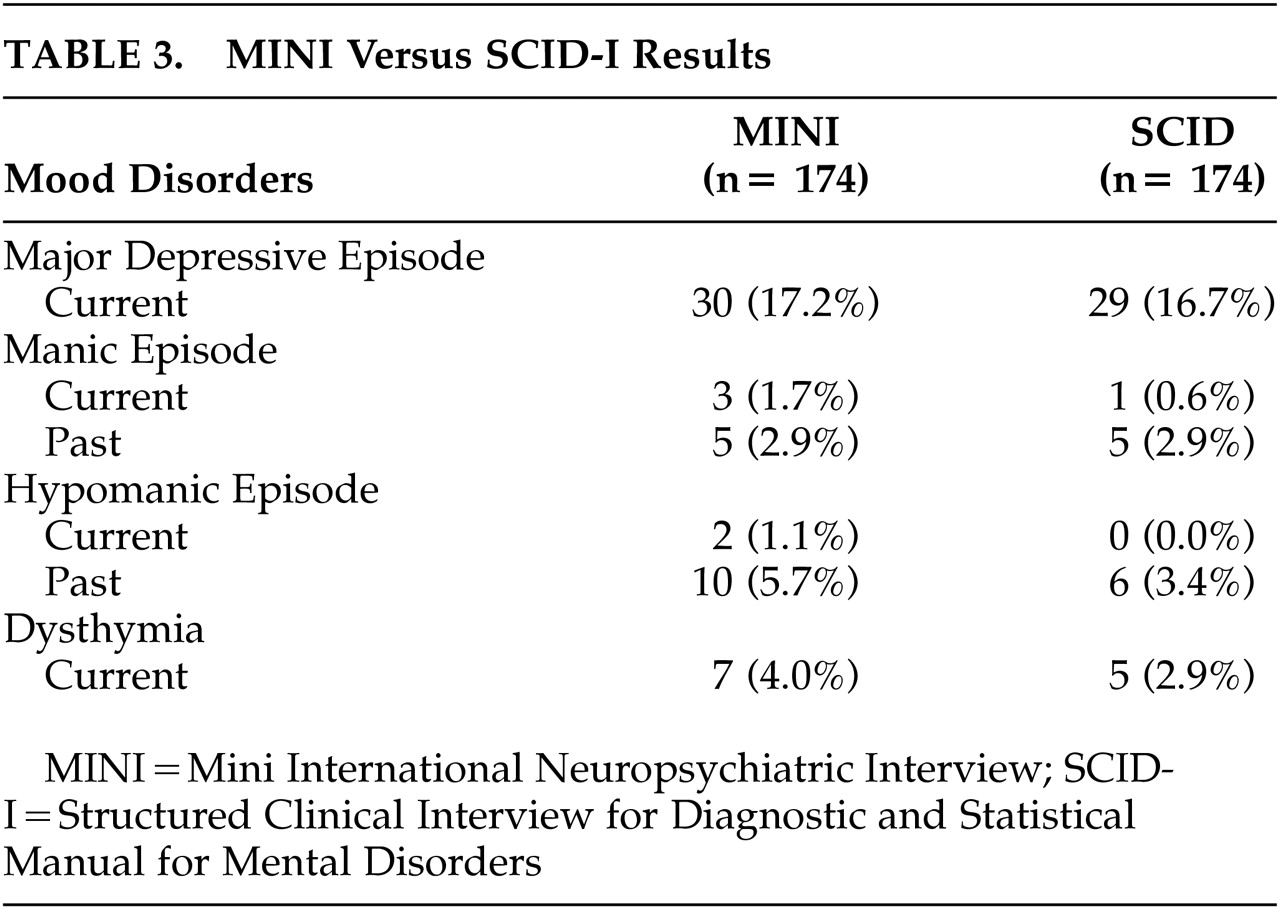

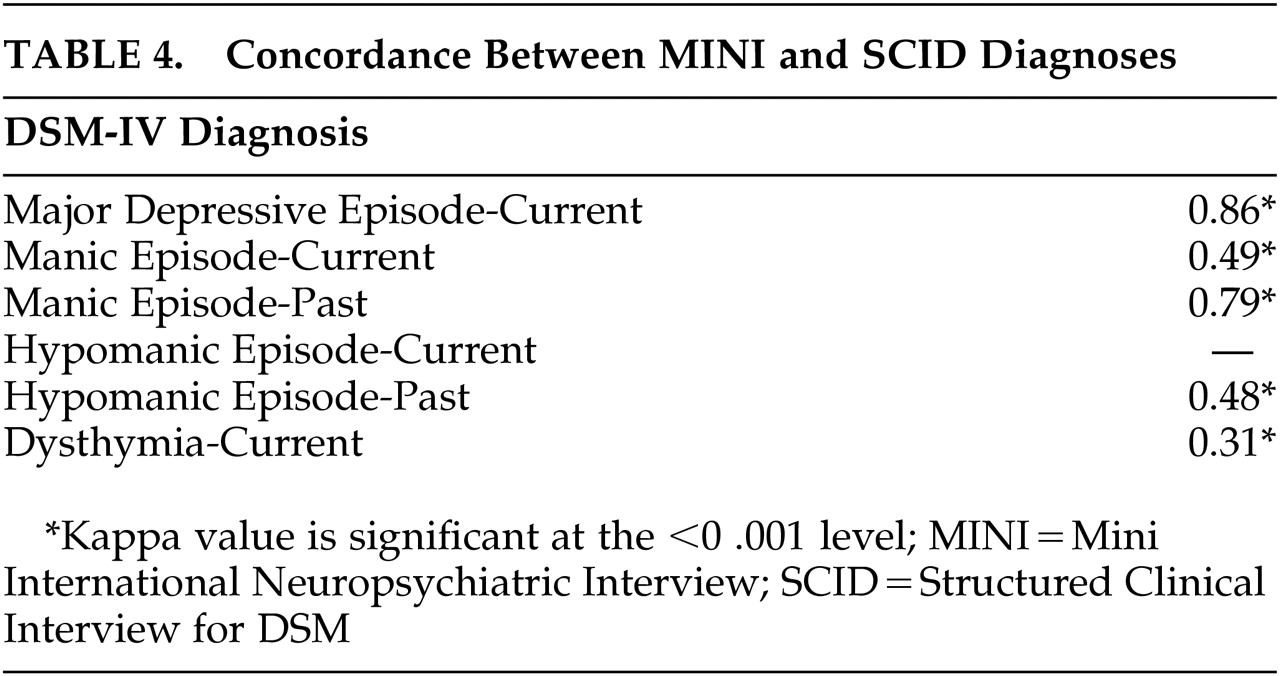

This multicenter investigation assessed a sample of outpatients with epilepsy followed at university-based clinics using standardized psychiatric interview procedures in order to characterize the rate of current major Axis I DSM–IV disorders. Patients were interviewed with a standardized protocol (MINI) that is more economical in its time demands and therefore of potential utility in clinical settings. Additionally, the mood disorder module of the SCID-I was administered in order to determine the validity of MINI diagnoses of depression compared to the research standard. The discussion that follows reviews the rates and distribution of current Axis I DSM–IV disorders using the MINI, and the validity of MINI mood disorder diagnoses compared to the research standard, and concludes with a brief review of issues related to the comorbidity, recognition, and treatment of current DSM–IV disorders in patients with chronic epilepsy.

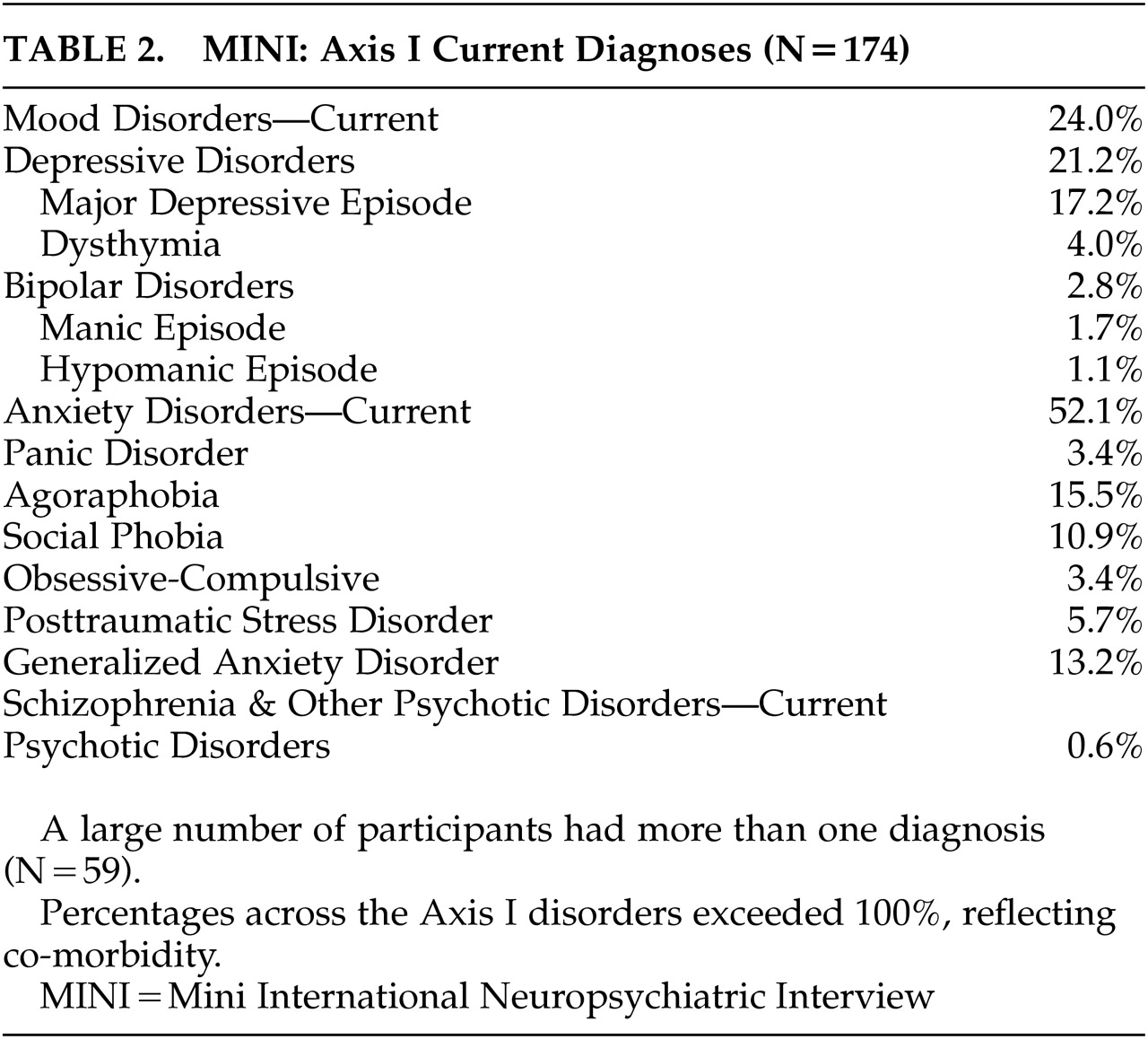

Rates of Current Axis I DSM–IV Disorders

Rates of current Axis I DSM–IV disorders using the MINI were found to be common, affecting essentially one-half of the sample. This rate of current Axis I disorders is elevated compared to findings derived from population-based studies such as the National Comorbidity Survey in which 48% of patients had a lifetime history of Axis I disorders.

24Most but not all investigations using standardized DSM-based structured interviews in the epilepsy literature have involved patients who were candidates for epilepsy surgery, most often with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy (e.g., references 13–18). Comparatively less research has been devoted to characterizing the distribution of Axis I disorders in the general population of patients with epilepsy attending specialty clinics. Nonetheless, the rate reported here (49%) is within the range (19%–62%) of current Axis I disorders in the few other available studies of patients with epilepsy that have reported this statistic.

17,28,29 Overall, these findings warrant a heightened index of concern for psychiatric morbidity in comparable specialty clinic settings.

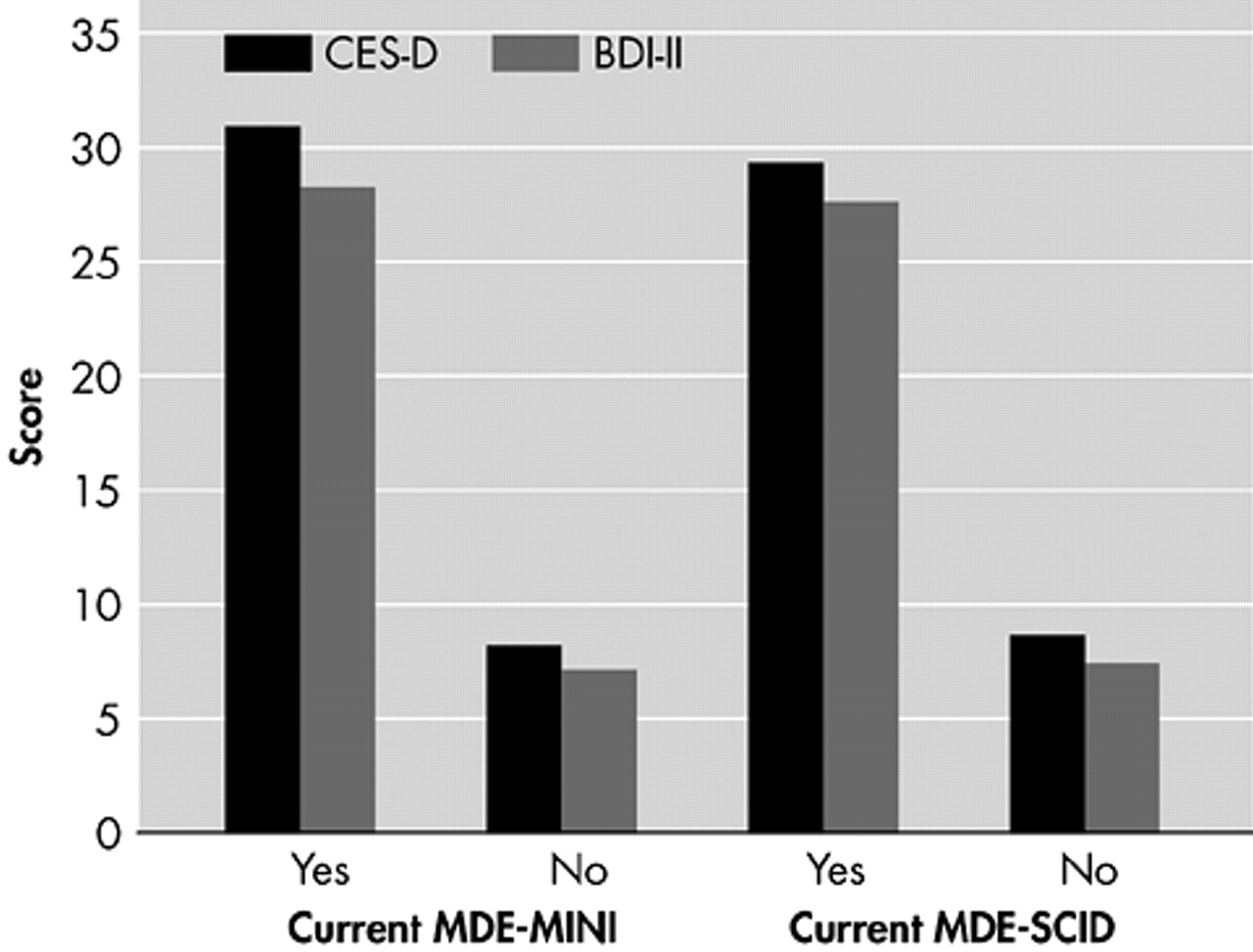

Of the epilepsy patients with identified current disorders, 21.2% met criteria for depressive disorders, including current major depression (17.2%). Interestingly, anxiety disorders were unexpectedly common current disorders, with agoraphobia (15.5%), generalized anxiety disorders (13.2%), and social phobia (10.9%) being the most common. As noted previously, most studies examining patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, have reported lifetime-to-date mood disorders to be more common than anxiety disorders. This pattern has been reported by several investigators including Victoroff

30 (63% mood versus 32% anxiety), Altshuler et al.

13 (44% versus 5%), Silberman et al.

18 (62% versus 15%), and Hermann et al.

4 (46% versus 13%). The rate of current major depression in these epilepsy subjects (17.2%) is considerably higher than that reported in the general population (10%).

24The high rate of anxiety disorders found here was unexpected. This sample included individuals with a range of seizure types. Individuals studied here did not undergo ictal monitoring as part of the research protocol, so the relationship between mood versus anxiety disorders and seizure type could not be directly addressed in this investigation. However, there were no significant differences between individuals with complex partial seizures with and without secondary generalized seizures in terms of the frequency of mood (p=0.74) and anxiety (p=0.20) disorders in general or more specifically major depression (p=0.57).

In summary, in this sample of individuals with chronic epilepsy, major depression (17%) was the most common current Axis I DSM–IV diagnosis, followed by agoraphobia (15%), generalized anxiety disorder (13%) and social phobia (11%). The broader trend, however, revealed overrepresentation of anxiety (52.1%) compared to mood disorders (24.0%).

Recognition and Treatment of Psychiatric Morbidity

Consistent with previous reports,

2,6,7–9 we found that mood disorders in epilepsy, including current major depression, often went untreated. Fewer than one-half (43%) of the patients with current major depression in this investigation were treated with antidepressant medications. The reasons for the undertreatment of depression in the general population have been reviewed previously,

31 but remain to be characterized in epilepsy. While high rates of untreated depression typically raise the index of suspicion that psychiatric comorbidity is inadequately screened for by attending physicians,

31 one interesting finding suggests that epilepsy specialists were concerned about and looking for comorbid mood disorders. A subset of 20 (11.5%) individuals was identified who were prescribed antidepressant medications, but they did not meet criteria for current major depression or a current mood disorder more generally. The nature of this subset of individuals remains uncertain and could reflect persons with subsyndromal depressive disorders, mood disorders that are adequately treated and no longer clinically manifest, or perhaps receiving antidepressant treatment that is not clinically warranted. Review of SCID-Iata for these 20 individuals, however, revealed that 60% suffered a past (but not current) major depressive episode, suggesting that treatment may have been appropriately targeted in the majority of cases. This subset of patients also raises the possibility that mood disorders may be even more common than our figures indicate.

Another interesting consideration is related to the individuals (43%) with current major depression who were treated with antidepressant medications. Despite receiving treatment, these individuals continued to meet criteria for major depression, suggesting that their depression had not responded to adequate treatment, the antidepressant treatment was suboptimal, patients suffered from drug resistant depression, or perhaps patients were noncompliant with their antidepressant treatment.

Overall, these results suggest that treating physicians are attempting to identify and treat comorbid mood disorders in particular, but they overlook one-half of the existing cases with current significant mood disorders, the vast majority of whom also suffer from comorbid anxiety disorders, and apparently are having difficulty controlling depressive symptoms in treated patients.

Several investigative groups in the epilepsy literature have pointed to the need for improved recognition of depression, unquestionably an important goal. However, the primary care literature has demonstrated that attempts to improve recognition of depression do not invariably translate to improved treatment of depression.

31 In the epilepsy literature, intervention papers typically focus on the standard of care for the treatment of depression in epilepsy,

2,32 with the assumption that this information will be incorporated into the usual and typical care of patients with epilepsy by their primary physicians, subsequently improving psychiatric outcomes. However, randomized treatment trials in other (non-neurological) health care settings have challenged this assumption. These studies have demonstrated the cost-effective and treatment-effective superiority of programs of so-called collaborative care (e.g., combined psychiatry and primary medical) over improved usual care for the management of major depression.

33–36 Such issues have yet to be examined seriously in epilepsy, as do issues related to the additional health care costs and associated functional disabilities

37,38 that have been demonstrated to be associated with major depression in other patient populations. Finally, anxiety disorders appear especially common in this population, and similar data collection regarding the recognition and adequacy of treatment of these disorders remains an important task for the future.